Far-sightedness

| Far-sightedness | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Hypermetropia, hyperopia, longsightedness, long-sightedness[1] | |

| |

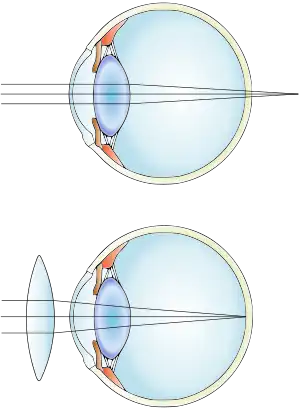

| Far-sightedness without (top) and with lens correction (bottom) | |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology, optometry |

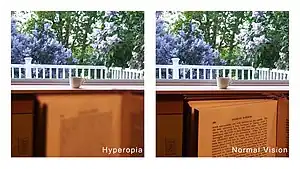

| Symptoms | Close objects appear blurry[2] |

| Complications | Accommodative dysfunction, binocular dysfunction, amblyopia, strabismus[3] |

| Causes | Too short an eyeball, misshapen lens or cornea[2] |

| Risk factors | Family history[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Eye exam[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Amblyopia, retrobulbar optic neuropathy, retinitis pigmentosa sine pigmento[4] |

| Treatment | Eyeglasses, contact lenses, surgery[2] |

| Frequency | ~7.5% (US)[2] |

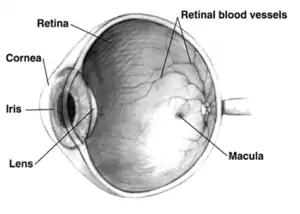

Far-sightedness, also known as hypermetropia, is a condition of the eye in which light is focused behind, instead of on, the retina.[2] This results in close objects appearing blurry, while far objects may appear normal.[2] As the condition worsens, objects at all distances may be blurry.[2] Other symptoms may include headaches and eye strain.[2] People may also experience accommodative dysfunction, binocular dysfunction, amblyopia, and strabismus.[3]

The cause is an imperfection of the eyes.[2] Often it occurs when the eyeball is too short, or the lens or cornea is misshapen.[2] Risk factors include a family history of the condition, diabetes, certain medications, and tumors around the eye.[2][4] It is a type of refractive error.[2] Diagnosis is based on an eye exam.[2]

Management can occur with eyeglasses, contact lenses, or surgery.[2] Glasses are easiest while contact lenses can provide a wider field of vision.[2] Surgery works by changing the shape of the cornea.[2] Far-sightedness primarily affects young children, with rates of 8% at 6 years and 1% at 15 years.[5] It then becomes more common again after the age of 40, affecting about half of people.[4]

Signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of far-sightedness are blurry vision, headaches, and eye strain.[2] The common symptom is eye strain. Difficulty seeing with both eyes (binocular vision) may occur, as well as difficulty with depth perception.[1]

Causes

Simple hypermetropia, the commonest form of hypermetropia is caused by normal biological variations in the development of eyeball.[6] Aetiologically, causes of hypermetropia can be classified as:

- Axial: Axial hypermetropia occur when the axial length of eyeball is too short. About 1 mm decrease in axial length cause 3 diopters of hypermetropia.[6] One condition that cause axial hypermetropia is nanophthalmos.[7]

- Curvatural: Curvatural hypermetropia occur when curvature of lens or cornea is flatter than normal. About 1 mm increase in radius of curvature results in 6 diopters of hypermetropia.[6] Cornea is flatter in microcornea and cornea plana.[7]

- Index: Age related changes in refractive index (cortical sclerosis) can cause hypermetropia. Another cause of index hypermetropia is diabetis.[6] Occasionally, mild hypermetropic shift may be seen in association with cortical or subcapsular cataract also.[7]

- Positional: Positional hypermetropia occur due to posterior dislocation of Lens or IOL.[6]

- Consecutive: Consecutive hypermetropia occur due to surgical over correction of myopia or surgical under correction in cataract surgery.[6]

- Functional: Functional hypermetropia results from paralysis of accommodation as seen in internal ophthalmoplegia, CN III palsy etc.[6]

- Absence of lens: Congenital or acquired aphakia cause high degree hypermetropia.[8]

Far-sightedness is often present from birth, but children have a very flexible eye lens, which helps to compensate.[9] In rare instances hyperopia can be due to diabetes, and problems with the blood vessels in the retina.[1]

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of far-sightedness is made by utilizing either a retinoscope or an automated refractor-objective refraction; or trial lenses in a trial frame or a phoropter to obtain a subjective examination. Ancillary tests for abnormal structures and physiology can be made via a slit lamp test, which examines the cornea, conjunctiva, anterior chamber, and iris.[10][11]

In severe cases of hyperopia from birth, in regards to preterm infants seem to have a higher incidence.[12] A child with severe hyperopia can't see objects in detail. If the brain never learns to see objects in detail, then there is a high chance of one eye becoming dominant. The result is that the brain will block the impulses of the non-dominant eye. [13]

Classification

Hyperopia is typically classified according to several aspects, there are three clinical categories of hyperopia.[3]

- Simple hyperopia: Occurs naturally due to biological diversity.

- Pathological hyperopia: Caused by disease, trauma, or abnormal development.

- Functional hyperopia: Caused by paralysis that interferes eye's ability to accommodate.

Classification according to severity

There are also three categories severity:[3]

- Low: Refractive error less than or equal to +2.00 diopters (D).

- Moderate: Refractive error greater than +2.00 D up to +5.00 D.

- High: Refractive error greater than +5.00 D.

Accomodation has significant role in hyperopia. Considering accommodative status, hyperopia can be classified as:[14][6]

- Total hypermetropia: It is the total amount of hyperopia which is obtained after complete relaxation of accommodation using cycloplegics like atropine.

- Latent hyperopia: It is the amount of hyperopia normally corrected by ciliary tone (approximately 1 diopter).

- Manifest hyperopia: It is the amount of hyperopia not corrected by ciliary tone. Manifest hyperopia is further classified into two, facultative and absolute.

- Facultative hyperopia: It is the part of hyperopia corrected by patient's accommodation.

- Absolute hyperopia: It is the residual part of hyperopia which causes blurring of vision for distance.

So, Total hyperopia= latent hyperopia + manifest hyperopia (facultative + absolute)[14]

Treatment

Corrective lenses

The simplest form of treatment for far-sightedness is the use of corrective lenses, eyeglasses or contact lenses.[15][16] Eyeglasses used to correct far-sightedness have convex lenses.[17]

Surgery

Laser procedures

- Photorefractive keratectomy (PRK): This is a refractive technique that is done by removal of a minimal amount of the corneal surface.[17][18] Hyperopic PRK has many complications like regression effect, astigmatism due to epithelial healing, and corneal haze.[19] Post operative epithelial healing time is also more for PRK.[20]

- Laser assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK): Laser eye surgery to reshape the cornea, so that glasses or contact lenses are no longer needed.[18][21] Excimer laser LASIK can correct hypermetropia upto +6 diopters.[19] LASIK is contraindicated in patients with lupus and rheumatoid arthritis.[19]

- Laser epithelial keratomileusis (LASEK): Resembles PRK, but uses alcohol to loosen the corneal surface.[17]

- Epi-LASIK: Epi-LASIK is also used to correct hyperopia.[20] In this procedure, use of epikeratome eliminates the use of alcohol.[20]

- Laser thermal keratoplasty (LTK): Laser thermal keratoplasty is a laser based non-destructive refractive procedure used to correct hyperopia and presbyopia.[20] It uses Thallium-Holmium-Chromium (THC): YAG laser.[20]

IOL implantation

- Ahakia correction: High degree hypermetropia due to absence of lens (aphakia) is best corrected using intraocular lens implantation.[22]

- Refractive lens exchange (RLE): A variation of cataract surgery where the natural crystalline lens is replaced with an artificial intraocular lens; the difference is the existence of abnormal ocular anatomy which causes a high refractive error.[23]

- Phakic IOL: Phakic intraocular lens are lenses that implanted inside eye without removing the normal crystalline lens. Phakic IOLs can be used to correct hypermetropia upto +20 diopters.[20]

Non laser procedures

- Conductive keratoplasty (CK): Conductive keratoplasty is a non laser refractive procedure used to correct presbyopia and low hypermetropia (+0.75D to +3.25D) with or without astigmatism (upto 0.75D).[20][24] It uses radiofrequency energy to heat and shrink corneal collagen tissue. CK is contraindicated in pregnant/breastfeeding women, central corneal dystrophies and scarring, history of herpetic keratitis, type 1 diabetes etc.[24]

- Automated lamellar keratoplasty (ALK): Hyperopic automated lamellar keratoplasty (H-ALK) and Homoplastic ALK are ALK procedures that corrects low to moderate hyperopia.[25] Poor predictability and the risk of complications limits usefulness of these procedures.[25]

- Keratophakia and epi-keratophakia are another two non laser surgical procedures used to correct hypermetropia.[25] Keratophakia is a surgical technique developed by Barraquer for treating high hypermetropia and aphakia. Poor predictability and induced irregular astigmatism are complications of these procedures.[25]

Etymology

The term hyperopia comes from Greek ὑπέρ hyper "over" and ὤψ ōps "sight" (GEN ὠπός ōpos).[26]

References

- 1 2 3 Lowth, Mary. "Long Sight (Hypermetropia)". Patient. Patient Platform Limited. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 "Facts About Hyperopia". NEI. July 2016. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Moore, Bruce D.; Augsburger, Arol R.; Ciner, Elise B.; Cockrell, David A.; Fern, Karen D.; Harb, Elise (2008). "Optometric Clinical Practice Guideline: Care of the Patient with Hyperopia" (PDF). American Optometric Association. pp. 2–3, 10–11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-07-17. Retrieved 2006-06-18.

- 1 2 3 Kaiser, Peter K.; Friedman, Neil J.; II, Roberto Pineda (2014). The Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary Illustrated Manual of Ophthalmology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 541. ISBN 9780323225274. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ↑ Castagno, VD; Fassa, AG; Carret, ML; Vilela, MA; Meucci, RD (23 December 2014). "Hyperopia: a meta-analysis of prevalence and a review of associated factors among school-aged children". BMC Ophthalmology. 14: 163. doi:10.1186/1471-2415-14-163. PMC 4391667. PMID 25539893.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Khurana, AK (September 2008). "Errors of refraction and binocular optical defects". Theory and practice of optics and refraction (2nd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 62–66. ISBN 978-81-312-1132-8.

- 1 2 3 John F., Salmon (2020). Kanski's clinical ophthalmology: a systematic approach (9th ed.). Edinburgh: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7020-7713-5. OCLC 1131846767.

- ↑ Khurana, AK (2015). "Errors of refraction and accommodation". Comprehensive ophthalmology (6th ed.). Jaypee, The Health Sciences Publisher. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-93-86056-59-7.

- ↑ "Normal, near-sightedness, and far-sightedness". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- ↑ "Farsightedness". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2016-02-24. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- ↑ "Slit-lamp exam". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- ↑ Brodsky, Dara; Ouellette, Mary Ann (2008). Primary care of the premature infant. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders. p. 230. ISBN 978-1-4160-0039-6. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2020-10-31.

- ↑ "Amblyopia (Lazy Eye) | National Eye Institute". www.nei.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- 1 2 Pablo, Artal (2017). Handbook of visual optics-Fundamentals and eye optics and. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4822-3785-6.

- ↑ Chou, Roger; Dana, Tracy; Bougatsos, Christina (2011-02-01). "Introduction". Screening for Visual Impairment in Children Ages 1-5 Years: Systematic Review to Update the 2004 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation (Report). Evidence Syntheses. Vol. 81. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08 – via PubMed Health.

- ↑ "Farsightedness (Hyperopia): Treatments". PubMed Health. U. S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- 1 2 3 "Treating long-sightedness". NHS Choices. National Health Service. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- 1 2 Settas, George; Settas, Clare; Minos, Evangelos; Yeung, Ian Yl (2012-01-01). "Photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) versus laser assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) for hyperopia correction". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (6): CD007112. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007112.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 22696365.

- Lay summary in: PubMed Health. 2012-02-17 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0014320/.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

- Lay summary in: PubMed Health. 2012-02-17 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0014320/.

- 1 2 3 Arun C, Gulani (9 November 2019). "LASIK Hyperopia: Background, History of the Procedure, Problem". Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Khurana, AK. "Refractive surgery". Theory and practice of optics and refraction (2nd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 307–348. ISBN 978-81-312-1132-8.

- ↑ "Laser Eye Surgery". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on 2016-03-06. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- ↑ Nema, H. V.; Nema, Nitin. Textbook of Ophthalmology. JP Medical Ltd. p. 287. ISBN 978-93-5025-507-0. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ↑ Alió, Jorge L.; Grzybowski, Andrzej; Romaniuk, Dorota (2014-12-10). "Refractive lens exchange in modern practice: when and when not to do it?". Eye and Vision. 1: 10. doi:10.1186/s40662-014-0010-2. ISSN 2326-0254. PMC 4655463. PMID 26605356.

- 1 2 "Conductive Keratoplasty". eyewiki.aao.org. Archived from the original on 2020-08-12. Retrieved 2020-07-29.

- 1 2 3 4 Refractive surgery. Azar, Dimitri T. (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Mosby / Elsevier. 2007. ISBN 0-323-03599-X. OCLC 853286620.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ "hyperopia". Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |