Iodine-131

| General | |

|---|---|

| Symbol | 131I |

| Names | iodine-131, I-131, radioiodine |

| Protons | 53 |

| Neutrons | 78 |

| Nuclide data | |

| Half-life | 8.0197 days |

| Isotope mass | 130.9061246(12) u |

| Excess energy | 971 keV |

| Isotopes of iodine Complete table of nuclides | |

Iodine-131 (131I, I-131) is an important radioisotope of iodine discovered by Glenn Seaborg and John Livingood in 1938 at the University of California, Berkeley.[1] It has a radioactive decay half-life of about eight days. It is associated with nuclear energy, medical diagnostic and treatment procedures, and natural gas production. It also plays a major role as a radioactive isotope present in nuclear fission products, and was a significant contributor to the health hazards from open-air atomic bomb testing in the 1950s, and from the Chernobyl disaster, as well as being a large fraction of the contamination hazard in the first weeks in the Fukushima nuclear crisis. This is because 131I is a major fission product of uranium and plutonium, comprising nearly 3% of the total products of fission (by weight). See fission product yield for a comparison with other radioactive fission products. 131I is also a major fission product of uranium-233, produced from thorium.

Due to its mode of beta decay, iodine-131 causes mutation and death in cells that it penetrates, and other cells up to several millimeters away. For this reason, high doses of the isotope are sometimes less dangerous than low doses, since they tend to kill thyroid tissues that would otherwise become cancerous as a result of the radiation. For example, children treated with moderate dose of 131I for thyroid adenomas had a detectable increase in thyroid cancer, but children treated with a much higher dose did not.[2] Likewise, most studies of very-high-dose 131I for treatment of Graves' disease have failed to find any increase in thyroid cancer, even though there is linear increase in thyroid cancer risk with 131I absorption at moderate doses.[3] Thus, iodine-131 is increasingly less employed in small doses in medical use (especially in children), but increasingly is used only in large and maximal treatment doses, as a way of killing targeted tissues. This is known as "therapeutic use".

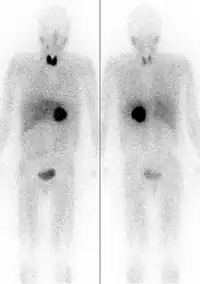

Iodine-131 can be "seen" by nuclear medicine imaging techniques (i.e., gamma cameras) whenever it is given for therapeutic use, since about 10% of its energy and radiation dose is via gamma radiation. However, since the other 90% of radiation (beta radiation) causes tissue damage without contributing to any ability to see or "image" the isotope, other less-damaging radioisotopes of iodine such as iodine-123 (see isotopes of iodine) are preferred in situations when only nuclear imaging is required. The isotope 131I is still occasionally used for purely diagnostic (i.e., imaging) work, due to its low expense compared to other iodine radioisotopes. Very small medical imaging doses of 131I have not shown any increase in thyroid cancer. The low-cost availability of 131I, in turn, is due to the relative ease of creating 131I by neutron bombardment of natural tellurium in a nuclear reactor, then separating 131I out by various simple methods (i.e., heating to drive off the volatile iodine). By contrast, other iodine radioisotopes are usually created by far more expensive techniques, starting with cyclotron radiation of capsules of pressurized xenon gas.[4]

Iodine-131 is also one of the most commonly used gamma-emitting radioactive industrial tracer. Radioactive tracer isotopes are injected with hydraulic fracturing fluid to determine the injection profile and location of fractures created by hydraulic fracturing.[5]

Much smaller incidental doses of iodine-131 than those used in medical therapeutic procedures, are supposed by some studies to be the major cause of increased thyroid cancers after accidental nuclear contamination. These studies suppose that cancers happen from residual tissue radiation damage caused by the 131I, and should appear mostly years after exposure, long after the 131I has decayed.[6][7] Other studies did not find a correlation.[8][9]

Production

Most 131I production is from neutron irradiation of a natural tellurium target in a nuclear reactor. Irradiation of natural tellurium produces almost entirely 131I as the only radionuclide with a half-life longer than hours, since most lighter isotopes of tellurium become heavier stable isotopes, or else stable iodine or xenon. However, the heaviest naturally occurring tellurium nuclide, 130Te (34% of natural tellurium) absorbs a neutron to become tellurium-131, which beta decays with a half-life of 25 minutes to 131I.

A tellurium compound can be irradiated while bound as an oxide to an ion exchange column, with evolved 131I then eluted into an alkaline solution.[10] More commonly, powdered elemental tellurium is irradiated and then 131I separated from it by dry distillation of the iodine, which has a far higher vapor pressure. The element is then dissolved in a mildly alkaline solution in the standard manner, to produce 131I as iodide and hypoiodate (which is soon reduced to iodide).[11]

131I is a fission product with a yield of 2.878% from uranium-235,[12] and can be released in nuclear weapons tests and nuclear accidents. However, the short half-life means it is not present in significant quantities in cooled spent nuclear fuel, unlike iodine-129 whose half-life is nearly a billion times that of 131I.

It is discharged to the atmosphere in small quantities by some nuclear power plants.[13]

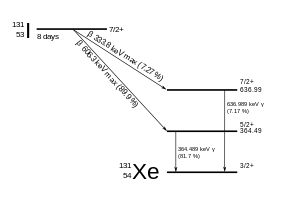

Radioactive decay

131I decays with a half-life of 8.02 days with beta minus and gamma emissions. This isotope of iodine has 78 neutrons in its nucleus, while the only stable nuclide, 127I, has 74. On decaying, 131I most often (89% of the time) expends its 971 keV of decay energy by transforming into stable xenon-131 in two steps, with gamma decay following rapidly after beta decay:

The primary emissions of 131I decay are thus electrons with a maximal energy of 606 keV (89% abundance, others 248–807 keV) and 364 keV gamma rays (81% abundance, others 723 keV).[14] Beta decay also produces an antineutrino, which carries off variable amounts of the beta decay energy. The electrons, due to their high mean energy (190 keV, with typical beta-decay spectra present) have a tissue penetration of 0.6 to 2 mm.[15]

Effects of exposure

Iodine in food is absorbed by the body and preferentially concentrated in the thyroid where it is needed for the functioning of that gland. When 131I is present in high levels in the environment from radioactive fallout, it can be absorbed through contaminated food, and will also accumulate in the thyroid. As it decays, it may cause damage to the thyroid. The primary risk from exposure to 131I is an increased risk of radiation-induced cancer in later life. Other risks include the possibility of non-cancerous growths and thyroiditis.[3]

The risk of thyroid cancer in later life appears to diminish with increasing age at time of exposure. Most risk estimates are based on studies in which radiation exposures occurred in children or teenagers. When adults are exposed, it has been difficult for epidemiologists to detect a statistically significant difference in the rates of thyroid disease above that of a similar but otherwise-unexposed group.[3][17]

The risk can be mitigated by taking iodine supplements, raising the total amount of iodine in the body and, therefore, reducing uptake and retention in the face and chest and lowering the relative proportion of radioactive iodine. However, such supplements were not consistently distributed to the population living nearest to the Chernobyl nuclear power plant after the disaster,[18] though they were widely distributed to children in Poland.

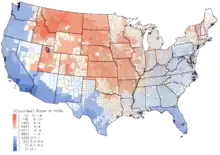

Within the US, the highest 131I fallout doses occurred during the 1950s and early 1960s to children having consumed fresh milk from sources contaminated as the result of above-ground testing of nuclear weapons.[6] The National Cancer Institute provides additional information on the health effects from exposure to 131I in fallout,[19] as well as individualized estimates, for those born before 1971, for each of the 3070 counties in the USA. The calculations are taken from data collected regarding fallout from the nuclear weapons tests conducted at the Nevada Test Site.[20]

On 27 March 2011, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health reported that 131I was detected in very low concentrations in rainwater from samples collected in Massachusetts, USA, and that this likely originated from the Fukushima power plant.[21] Farmers near the plant dumped raw milk, while testing in the United States found 0.8 pico-curies per liter of iodine-131 in a milk sample, but the radiation levels were 5,000 times lower than the FDA's "defined intervention level". The levels were expected to drop relatively quickly[22]

Treatment and prevention

A common treatment method for preventing iodine-131 exposure is by saturating the thyroid with regular, stable iodine-127, as an iodide or iodate salt. Free elemental iodine should not be used for saturating the thyroid because it is a corrosive oxidant and therefore is toxic to ingest in the necessary quantities.[23] The thyroid will absorb very little of the radioactive iodine-131 after it is saturated with non-radioactive iodide, thereby avoiding the damage caused by radiation from radioiodine.

Common treatment method

The most common method of treatment is to give potassium iodide to those at risk. The dosage for adults is 130 mg potassium iodide per day, given in one dose, or divided into portions of 65 mg twice a day. This is equivalent to 100 mg of iodine, and is about 700 times bigger than the nutritional dose of iodine, which is 0.150 mg per day (150 micrograms per day). See potassium iodide for more information on prevention of radioiodine absorption by the thyroid during nuclear accident, or for nuclear medical reasons. The FDA-approved dosing of potassium iodide for this purpose are as follows: infants less than 1 month old, 16 mg; children 1 month to 3 years, 32 mg; children 3 years to 18 years, 65 mg; adults 130 mg.[24] However, some sources recommend alternative dosing regimens.[25]

| Age | KI in mg | KIO3 in mg |

|---|---|---|

| Over 12 years old | 130 | 170 |

| 3–12 years old | 65 | 85 |

| 1–36 months old | 32 | 42 |

| < 1 month old | 16 | 21 |

The ingestion of prophylaxis iodide and iodate is not without its dangers, There is reason for caution about taking potassium iodide or iodine supplements, as their unnecessary use can cause conditions such as the Jod-Basedow phenomena, and the Wolff–Chaikoff effect, trigger and/or worsen hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism respectively, and ultimately cause temporary or even permanent thyroid conditions. It can also cause sialadenitis (an inflammation of the salivary gland), gastrointestinal disturbances, allergic reactions and rashes.

Iodine tablet

The use of a particular "iodine tablet" used in portable water purification has also been determined as somewhat effective at reducing radioiodine uptake. In a small study on human subjects who, for each of their 90-day trial, ingested four 20 milligram tetraglycine hydroperiodide (TGHP) water tablets, with each tablet releasing 8 milligrams (ppm) of free titratable iodine;[27] it was found that the biological uptake of radioactive iodine in these human subjects dropped to and remained at a value of less than 2% the radioiodine uptake rate of that observed in control subjects who were fully exposed to radioiodine without treatment.[28]

Goitrogen

The administration of known goitrogen substances can also be used as a prophylaxis in reducing the bio-uptake of iodine, (whether it be the nutritional non-radioactive iodine-127 or radioactive iodine, radioiodine – most commonly iodine-131, as the body cannot discern between different iodine isotopes). Perchlorate ions, a common water contaminant in the USA due to the aerospace industry, has been shown to reduce iodine uptake and thus is classified as a goitrogen. Perchlorate ions are a competitive inhibitor of the process by which iodide, is actively deposited into thyroid follicular cells. Studies involving healthy adult volunteers determined that at levels above 0.007 milligrams per kilogram per day (mg/(kg·d)), perchlorate begins to temporarily inhibit the thyroid gland's ability to absorb iodine from the bloodstream ("iodide uptake inhibition", thus perchlorate is a known goitrogen).[29] The reduction of the iodide pool by perchlorate has dual effects—reduction of excess hormone synthesis and hyperthyroidism, on the one hand, and reduction of thyroid inhibitor synthesis and hypothyroidism on the other. Perchlorate remains very useful as a single dose application in tests measuring the discharge of radioiodide accumulated in the thyroid as a result of many different disruptions in the further metabolism of iodide in the thyroid gland.[30]

Thyrotoxicosis

Treatment of thyrotoxicosis (including Graves' disease) with 600–2,000 mg potassium perchlorate (430–1,400 mg perchlorate) daily for periods of several months or longer was once common practice, particularly in Europe,[29][31] and perchlorate use at lower doses to treat thyroid problems continues to this day.[32] Although 400 mg of potassium perchlorate divided into four or five daily doses was used initially and found effective, higher doses were introduced when 400 mg/day was discovered not to control thyrotoxicosis in all subjects.[29][30]

Current regimens for treatment of thyrotoxicosis (including Graves' disease), when a patient is exposed to additional sources of iodine, commonly include 500 mg potassium perchlorate twice per day for 18–40 days.[29][33]

Prophylaxis with perchlorate-containing water at concentrations of 17 ppm, which corresponds to 0.5 mg/kg-day personal intake, if one is 70 kg and consumes two litres of water per day, was found to reduce baseline radioiodine uptake by 67%[29] This is equivalent to ingesting a total of just 35 mg of perchlorate ions per day. In another related study where subjects drank just 1 litre of perchlorate-containing water per day at a concentration of 10 ppm, i.e. daily 10 mg of perchlorate ions were ingested, an average 38% reduction in the uptake of iodine was observed.[34]

However, when the average perchlorate absorption in perchlorate plant workers subjected to the highest exposure has been estimated as approximately 0.5 mg/kg-day, as in the above paragraph, a 67% reduction of iodine uptake would be expected. Studies of chronically exposed workers though have thus far failed to detect any abnormalities of thyroid function, including the uptake of iodine.[35] This may well be attributable to sufficient daily exposure or intake of healthy iodine-127 among the workers and the short 8-hr biological half life of perchlorate in the body.[29]

Uptake of iodine-131

To completely block the uptake of iodine-131 by the purposeful addition of perchlorate ions to a population's water supply, aiming at dosages of 0.5 mg/kg-day, or a water concentration of 17 ppm, would therefore be grossly inadequate at truly reducing radioiodine uptake. Perchlorate ion concentrations in a region's water supply would therefore need to be much higher, with at least a total dosage of 7.15 mg/kg of body weight per day needing to be aimed for, with this being achievable for most adults by consuming 2 liters of water per day with a water concentration of 250 mg/kg of water, or 250 ppm of perchlorate ions per liter; only at this level would perchlorate consumption offer adequate protection, and be truly beneficial to the population at preventing bioaccumulation when exposed to a radioiodine environment.[29][33] This being entirely independent of the availability of iodate or iodide drugs.

The continual addition of perchlorate to the water supply would need to continue for no less than 80–90 days, beginning immediately after the initial release of radioiodine is detected; after 80–90 days have passed, released radioactive iodine-131 will have decayed to less than 0.1% of its initial quantity, and thus the danger from biouptake of iodine-131 is essentially over.[36]

Radioiodine release

In the event of a radioiodine release, the ingestion of prophylaxis potassium iodide or iodate, if available, would rightly take precedence over perchlorate administration, and would be the first line of defense in protecting the population from a radioiodine release. However, in the event of a radioiodine release too massive and widespread to be controlled by the limited stock of iodide & iodate prophylaxis drugs, then the addition of perchlorate ions to the water supply, or distribution of perchlorate tablets, would serve as a cheap and efficacious second line of defense against carcinogenic radioiodine bioaccumulation.

The ingestion of goitrogen drugs is, much like potassium iodide, also not without its dangers, such as hypothyroidism. In all these cases however, despite the risks, the prophylaxis benefits of intervention with iodide, iodate, or perchlorate outweigh the serious cancer risk from radioiodine bioaccumulation in regions where radioiodine has sufficiently contaminatated the environment.

Medical use

Iodine-131 is used for unsealed source radiotherapy in nuclear medicine to treat several conditions. It can also be detected by gamma cameras for diagnostic imaging, however it is rarely administered for diagnostic purposes only, imaging will normally be done following a therapeutic dose.[38] Use of the 131I as iodide salt exploits the mechanism of absorption of iodine by the normal cells of the thyroid gland.

Treatment of thyrotoxicosis

Major uses of 131I include the treatment of thyrotoxicosis (hyperthyroidism) due to Graves' disease, and sometimes hyperactive thyroid nodules (abnormally active thyroid tissue that is not malignant). The therapeutic use of radioiodine to treat hyperthyroidism from Graves' disease was first reported by Saul Hertz in 1941. The dose is typically administered orally (either as a liquid or capsule), in an outpatient setting, and is usually 400–600 megabecquerels (MBq).[39] Radioactive iodine (iodine-131) alone can potentially worsen thyrotoxicosis in the first few days after treatment. One side effect of treatment is an initial period of a few days of increased hyperthyroid symptoms. This occurs because when the radioactive iodine destroys the thyroid cells, they can release thyroid hormone into the blood stream. For this reason, sometimes patients are pre-treated with thyrostatic medications such as methimazole, and/or they are given symptomatic treatment such as propranolol. Radioactive iodine treatment is contraindicated in breast-feeding and pregnancy[40]

Treatment of thyroid cancer

Iodine-131, in higher doses than for thyrotoxicosis, is used for ablation of remnant thyroid tissue following a complete thyroidectomy to treat thyroid cancer.[41][39]

Administration of I-131 for ablation

Typical therapeutic doses of I-131 are between 2220 and 7400 megabecquerels (MBq).[42] Because of this high radioactivity and because the exposure of stomach tissue to beta radiation would be high near an undissolved capsule, I-131 is sometimes administered to human patients in a small amount of liquid. Administration of this liquid form is usually by straw which is used to slowly and carefully suck up the liquid from a shielded container.[43] For administration to animals (for example, cats with hyperthyroidism), for practical reasons the isotope must be administered by injection. European guidelines recommend administration of a capsule, due to "greater ease to the patient and the superior radiation protection for caregivers".[44]

Post-treatment isolation

Ablation doses are usually administered on an inpatient basis, and IAEA International Basic Safety Standards recommend that patients are not discharged until the activity falls below 1100 MBq.[45] ICRP advice states that "comforters and carers" of patients undergoing radionuclide therapy should be treated as members of the public for dose constraint purposes and any restrictions on the patient should be designed based on this principle.[46]

Patients receiving I-131 radioiodine treatment may be warned not to have sexual intercourse for one month (or shorter, depending on dose given), and women told not to become pregnant for six months afterwards. "This is because a theoretical risk to a developing fetus exists, even though the amount of radioactivity retained may be small and there is no medical proof of an actual risk from radioiodine treatment. Such a precaution would essentially eliminate direct fetal exposure to radioactivity and markedly reduce the possibility of conception with sperm that might theoretically have been damaged by exposure to radioiodine."[47] These guidelines vary from hospital to hospital and will depend on national legislation and guidance, as well as the dose of radiation given. Some also advise not to hug or hold children when the radiation is still high, and a one- or two- metre distance to others may be recommended.[48]

I-131 will be eliminated from the body over the next several weeks after it is given. The majority of I-131 will be eliminated from the human body in 3–5 days, through natural decay, and through excretion in sweat and urine. Smaller amounts will continue to be released over the next several weeks, as the body processes thyroid hormones created with the I-131. For this reason, it is advised to regularly clean toilets, sinks, bed sheets and clothing used by the person who received the treatment. Patients may also be advised to wear slippers or socks at all times, and avoid prolonged close contact with others. This minimizes accidental exposure by family members, especially children.[49] Use of a decontaminant specially made for radioactive iodine removal may be advised. The use of chlorine bleach solutions, or cleaners that contain chlorine bleach for cleanup, are not advised, since radioactive elemental iodine gas may be released.[50] Airborne I-131 may cause a greater risk of second-hand exposure, spreading contamination over a wide area. Patient is advised if possible to stay in a room with a bathroom connected to it to limit unintended exposure to family members.

Many airports now have radiation detectors to detect the smuggling of radioactive materials. Patients should be warned that if they travel by air, they may trigger radiation detectors at airports up to 95 days after their treatment with 131I.[51]

Other therapeutic uses

The 131I isotope is also used as a radioactive label for certain radiopharmaceuticals that can be used for therapy, e.g. 131I-metaiodobenzylguanidine (131I-MIBG) for imaging and treating pheochromocytoma and neuroblastoma. In all of these therapeutic uses, 131I destroys tissue by short-range beta radiation. About 90% of its radiation damage to tissue is via beta radiation, and the rest occurs via its gamma radiation (at a longer distance from the radioisotope). It can be seen in diagnostic scans after its use as therapy, because 131I is also a gamma-emitter.

Diagnostic uses

Because of the carcinogenicity of its beta radiation in the thyroid in small doses, I-131 is rarely used primarily or solely for diagnosis (although in the past this was more common due to this isotope's relative ease of production and low expense). Instead the more purely gamma-emitting radioiodine iodine-123 is used in diagnostic testing (nuclear medicine scan of the thyroid). The longer half-lived iodine-125 is also occasionally used when a longer half-life radioiodine is needed for diagnosis, and in brachytherapy treatment (isotope confined in small seed-like metal capsules), where the low-energy gamma radiation without a beta component makes iodine-125 useful. The other radioisotopes of iodine are never used in brachytherapy.

The use of 131I as a medical isotope has been blamed for a routine shipment of biosolids being rejected from crossing the Canada—U.S. border.[52] Such material can enter the sewers directly from the medical facilities, or by being excreted by patients after a treatment

Industrial radioactive tracer uses

Used for the first time in 1951 to localize leaks in a drinking water supply system of Munich, Germany, iodine-131 became one of the most commonly used gamma-emitting industrial radioactive tracers, with applications in isotope hydrology and leak detection.[53][54][55][56]

Since the late 1940s, radioactive tracers have been used by the oil industry. Tagged at the surface, water is then tracked downhole, using the appropriated gamma detector, to determine flows and detect underground leaks. I-131 has been the most widely used tagging isotope in an aqueous solution of sodium iodide.[57][58][59] It is used to characterize the hydraulic fracturing fluid to help determine the injection profile and location of fractures created by hydraulic fracturing.[60][61][62]

See also

References

- ↑ "UW-L Brachy Course". wikifoundry. April 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ↑ Dobyns, B. M.; Sheline, G. E.; Workman, J. B.; Tompkins, E. A.; McConahey, W. M.; Becker, D. V. (June 1974). "Malignant and benign neoplasms of the thyroid in patients treated for hyperthyroidism: a report of the cooperative thyrotoxicosis therapy follow-up study". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 38 (6): 976–998. doi:10.1210/jcem-38-6-976. ISSN 0021-972X. PMID 4134013.

- 1 2 3 Rivkees, Scott A.; Sklar, Charles; Freemark, Michael (1998). "The Management of Graves' Disease in Children, with Special Emphasis on Radioiodine Treatment". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 83 (11): 3767–76. doi:10.1210/jc.83.11.3767. PMID 9814445.

- ↑ Rayyes, Al; Hamid, Abdul (2002). "Technical meeting of project counterparts on cyclotron production of I-123" (pdf). International Nuclear Information System. IAEA.

- ↑ Reis, John C. (1976). Environmental Control in Petroleum Engineering. Gulf Professional Publishers.

- 1 2 Simon, Steven L.; Bouville, André; Land, Charles E. (January–February 2006). "Fallout from Nuclear Weapons Tests and Cancer Risks". American Scientist. 94: 48–57. doi:10.1511/2006.1.48.

In 1997, NCI conducted a detailed evaluation of dose to the thyroid glands of U.S. residents from I-131 in fallout from tests in Nevada. (...) we evaluated the risks of thyroid cancer from that exposure and estimated that about 49,000 fallout-related cases might occur in the United States, almost all of them among persons who were under age 20 at some time during the period 1951–57, with 95-percent uncertainty limits of 11,300 and 212,000.

- ↑ "National Cancer Institute calculator for thyroid cancer risk as a result of I-131 intake after nuclear testing before 1971 in Nevada". Ntsi131.nci.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ↑ Guiraud-Vitaux, F.; Elbast, M.; Colas-Linhart, N.; Hindie, E. (February 2008). "Thyroid cancer after Chernobyl: is iodine 131 the only culprit ? Impact on clinical practice". Bulletin du Cancer. 95 (2): 191–5. doi:10.1684/bdc.2008.0574 (inactive 31 October 2021). PMID 18304904.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of October 2021 (link) - ↑ Centre for Disease Control (2002). The Hanford Thyroid Disease Study (PDF). Retrieved 17 June 2012.

no associations between Hanford's iodine-131 releases and thyroid disease were observed. [The findings] show that if there is an increased risk of thyroid disease from exposure to Hanford's iodine-131, it is probably too small to observe using the best epidemiologic methods available

Executive summary - ↑ Chattopadhyay, Sankha; Saha Das, Sujata (2010). "Recovery of 131I from alkaline solution of n-irradiated tellurium target using a tiny Dowex-1 column". Applied Radiation and Isotopes. 68 (10): 1967–9. doi:10.1016/j.apradiso.2010.04.033. PMID 20471848.

- ↑ "I-131 Fact Sheet" (PDF). Nordion. August 2011. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

- ↑ "Nuclear Data for Safeguards, Table C-3, Cumulative Fission Yields". International Atomic Energy Agency. Retrieved 14 March 2011. (thermal neutron fission)

- ↑ Effluent Releases from Nuclear Power Plants and Fuel-Cycle Facilities. National Academies Press (US). 29 March 2012.

- ↑ "Nuclide Safety Data Sheet" (PDF). Retrieved 26 October 2010.

- ↑ Skugor, Mario (2006). Thyroid Disorders. A Cleveland Clinic Guide. Cleveland Clinic Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-59624-021-6.

- ↑ Council, National Research (11 February 2003). Exposure of the American Population to Radioactive Fallout from Nuclear Weapons Tests: A Review of the CDC-NCI Draft Report on a Feasibility Study of the Health Consequences to the American Population from Nuclear Weapons Tests Conducted by the United States and Other Nations. nap.edu. doi:10.17226/10621. ISBN 978-0-309-08713-1. PMID 25057651. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ↑ Robbins, Jacob; Schneider, Arthur B. (2000). "Thyroid cancer following exposure to radioactive iodine". Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders. 1 (3): 197–203. doi:10.1023/A:1010031115233. ISSN 1389-9155. PMID 11705004. S2CID 13575769.

- ↑ Frot, Jacques. "The Causes of the Chernobyl Event". Ecolo.org. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ↑ "Radioactive I-131 from Fallout". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- ↑ "Individual Dose and Risk Calculator for Nevada Test Site fallout". National Cancer Institute. 1 October 2007. Archived from the original on 18 October 2007. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- ↑ "Low Concentrations Of Radiation Found In Mass. | WCVB Home – WCVB Home". Thebostonchannel.com. 27 March 2011. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ↑ "Traces of radioactive iodine found in Washington state milk" Los Angeles Times

- ↑ Sepe, S. M.; Clark, R. A. (March 1985). "Oxidant membrane injury by the neutrophil myeloperoxidase system. I. Characterization of a liposome model and injury by myeloperoxidase, hydrogen peroxide, and halides". Journal of Immunology. 134 (3): 1888–1895. ISSN 0022-1767. PMID 2981925.

- ↑ Kowalsky RJ, Falen, SW. Radiopharmaceuticals in Nuclear Pharmacy and Nuclear Medicine. 2nd ed. Washington DC: American Pharmacists Association; 2004.

- ↑ Olivier, Pierre; et al. (29 December 2002). "Guideline for Radioiodinated MIBG Scintigraphy in Children" (PDF). European Association of Nuclear Medicine. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ↑ Guidelines for Iodine Prophylaxis following Nuclear Accidents (PDF), Geneva: World Health Organization, 1999

- ↑ "Potable Aqua Questions and Answers". www.pharmacalway.com. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ↑ Lemar, H. J. (1995). "Thyroid adaptation to chronic tetraglycine hydroperiodide water purification tablet use". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 80 (1): 220–223. doi:10.1210/jc.80.1.220. PMID 7829615.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Greer, Monte A.; Goodman, Gay; Pleus, Richard C.; Greer, Susan E. (2002). "Health Effects Assessment for Environmental Perchlorate Contamination: The Dose Response for Inhibition of Thyroidal Radioiodine Uptake in Humans". Environmental Health Perspectives. 110 (9): 927–37. doi:10.1289/ehp.02110927. PMC 1240994. PMID 12204829.

- 1 2 Wolff, J. (1998). "Perchlorate and the thyroid gland". Pharmacological Reviews. 50 (1): 89–105. PMID 9549759.

- ↑ Barzilai, D.; Sheinfeld, M. (1966). "Fatal complications following use of potassium perchlorate in thyrotoxicosis. Report of two cases and a review of the literature". Israel Journal of Medical Sciences. 2 (4): 453–6. PMID 4290684.

- ↑ Woenckhaus, U.; Girlich, C. (2005). "Therapie und Prävention der Hyperthyreose" [Therapy and prevention of hyperthyroidism]. Der Internist (in German). 46 (12): 1318–23. doi:10.1007/s00108-005-1508-4. PMID 16231171. S2CID 13214666.

- 1 2 Bartalena, L.; Brogioni, S.; Grasso, L.; Bogazzi, F.; Burelli, A.; Martino, E. (1996). "Treatment of amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis, a difficult challenge: Results of a prospective study". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 81 (8): 2930–3. doi:10.1210/jc.81.8.2930. PMID 8768854.

- ↑ Lawrence, J. E.; Lamm, S. H.; Pino, S.; Richman, K.; Braverman, L. E. (2000). "The Effect of Short-Term Low-Dose Perchlorate on Various Aspects of Thyroid Function". Thyroid. 10 (8): 659–63. doi:10.1089/10507250050137734. PMID 11014310.

- ↑ Lamm, Steven H.; Braverman, Lewis E.; Li, Feng Xiao; Richman, Kent; Pino, Sam; Howearth, Gregory (1999). "Thyroid Health Status of Ammonium Perchlorate Workers: A Cross-Sectional Occupational Health Study". Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine. 41 (4): 248–60. doi:10.1097/00043764-199904000-00006. PMID 10224590.

- ↑ "Nuclear Chemistry: Half-Lives and Radioactive Dating – For Dummies". Dummies.com. 6 January 2010. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ↑ Nakajo, M., Shapiro, B. Sisson, J.C., Swanson, D.P., and Beierwaltes, W.H. Salivary gland uptake of Meta-[I131]Iodobenzylguanidine. J Nucl Med 25:2–6, 1984

- ↑ Carpi, Angelo; Mechanick, Jeffrey I. (2016). Thyroid Cancer: From Emergent Biotechnologies to Clinical Practice Guidelines. CRC Press. p. 148. ISBN 9781439862223.

- 1 2 Stokkel, Marcel P. M.; Handkiewicz Junak, Daria; Lassmann, Michael; Dietlein, Markus; Luster, Markus (13 July 2010). "EANM procedure guidelines for therapy of benign thyroid disease". European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 37 (11): 2218–2228. doi:10.1007/s00259-010-1536-8. PMID 20625722. S2CID 9062561.

- ↑ Brunton, Laurence L. et. al. Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 12e. 2011. Chapter 39

- ↑ Silberstein, E. B.; Alavi, A.; Balon, H. R.; Clarke, S. E. M.; Divgi, C.; Gelfand, M. J.; Goldsmith, S. J.; Jadvar, H.; Marcus, C. S.; Martin, W. H.; Parker, J. A.; Royal, H. D.; Sarkar, S. D.; Stabin, M.; Waxman, A. D. (11 July 2012). "The SNMMI Practice Guideline for Therapy of Thyroid Disease with 131I 3.0". Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 53 (10): 1633–1651. doi:10.2967/jnumed.112.105148. PMID 22787108. S2CID 13558098.

- ↑ Yama, Naoya; Sakata, Koh-ichi; Hyodoh, Hideki; Tamakawa, Mitsuharu; Hareyama, Masato (June 2012). "A retrospective study on the transition of radiation dose rate and iodine distribution in patients with I-131-treated well-differentiated thyroid cancer to improve bed control shorten isolation periods". Annals of Nuclear Medicine. 26 (5): 390–396. doi:10.1007/s12149-012-0586-3. ISSN 1864-6433. PMID 22382609. S2CID 19799564.

- ↑ Rao, V. P.; Sudhakar, P.; Swamy, V. K.; Pradeep, G.; Venugopal, N. (2010). "Closed system vacuum assisted administration of high dose radio iodine to cancer thyroid patients: NIMS techniqe". Indian J Nucl Med. 25 (1): 34–5. doi:10.4103/0972-3919.63601. PMC 2934601. PMID 20844671.

- ↑ Luster, M.; Clarke, S. E.; Dietlein, M.; Lassmann, M.; Lind, P.; Oyen, W. J. G.; Tennvall, J.; Bombardieri, E. (1 August 2008). "Guidelines for radioiodine therapy of differentiated thyroid cancer". European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 35 (10): 1941–1959. doi:10.1007/s00259-008-0883-1. PMID 18670773. S2CID 81465.

- ↑ Nuclear medicine in thyroid cancer management: a practical approach. Vienna: International Atomic Energy Agency. 2009. ISBN 978-92-0-113108-9.

- ↑ Valentine, J. (June 2004). "ICRP Publication 94: Release of Nuclear Medicine Patients after Therapy with Unsealed Sources". Annals of the ICRP. 34 (2): 1–27. doi:10.1016/j.icrp.2004.08.003. S2CID 71901469.

- ↑ "Radioiodine Therapy: Information for Patients" (PDF). AACE. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2008.

- ↑ "Instructions for Receiving Radioactive Iodine Therapy after a Thyroid Cancer Survey". University of Washington Medical Center. Archived from the original on 28 February 2009. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- ↑ "Precautions after Out-patient Radioactive Iodine (I-131) Therapy" (PDF). Department of Nuclear Medicine McMaster University Medical Centre. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2011.

- ↑ Biosafety Manual for Perdue University (PDF). Indianapolis. 2002. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ↑ Sutton, Jane (29 January 2007). "Radioactive patients". reuters. Retrieved 15 May 2009.

- ↑ "Medical isotopes the likely cause of radiation in Ottawa waste". CBC News. 4 February 2009. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ↑ Moser, H.; Rauert, W. (2007). "Isotopic Tracers for Obtaining Hydrologic Parameters". In Aggarwal, Pradeep K.; Gat, Joel R.; Froehlich, Klaus F. (eds.). Isotopes in the water cycle : past, present and future of a developing science. Dordrecht: Springer. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-4020-6671-9. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ↑ Rao, S. M. (2006). "Radioisotopes of hydrological interest". Practical isotope hydrology. New Delhi: New India Publishing Agency. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-81-89422-33-2. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ↑ "Investigating leaks in Dams & Reservoirs" (PDF). IAEA.org. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ↑ Araguás, Luis Araguás; Plata Bedmar, Antonio (2002). "Artificial radioactive tracers". Detection and prevention of leaks from dams. Taylor & Francis. pp. 179–181. ISBN 978-90-5809-355-4. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ↑ Reis, John C. (1976). "Radioactive materials". Environmental Control in Petroleum Engineering. Gulf Professional Publishers. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-88415-273-6.

- ↑ McKinley, R. M. (1994). "Radioactive tracer surveys" (PDF). Temperature, radioactive tracer, and noise logging for injection well integrity. Washington: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ↑ Schlumberger Ltd. "Radioactive-tracer log". Schlumberger.com. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ↑ US patent 5635712, Scott, George L., "Method for monitoring the hydraulic fracturing of a subterranean formation", published 1997-06-03

- ↑ US patent 4415805, Fertl, Walter H., "Method and apparatus for evaluating multiple stage fracturing or earth formations surrounding a borehole", published 1983-11-15

- ↑ US patent 5441110, Scott, George L., "System and method for monitoring fracture growth during hydraulic fracture treatment", published 1995-08-15

External links

- "ANL factsheet" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2003.

- RadiologyInfo – The radiology information resource for patients: Radioiodine (I −131) Therapy

- Case Studies in Environmental Medicine: Radiation Exposure from Iodine 131

- Sensitivity of Personal Homeland Security Radiation Detectors to Medical Radionuclides and Implications for Counseling of Nuclear Medicine Patients

- NLM Hazardous Substances Databank – Iodine, Radioactive