Lemierre syndrome

| Lemierre syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Lemierre's syndrome,[1] postanginal septicemia,[1] necrobacillosis,[1] septic phlebitis of the internal jugular vein, postanginal sepsis secondary to oropharyngeal infection, Lemierre's disease | |

| |

| Fusobacterium necrophorum, the most common bacteria involved in Lemierre | |

| Specialty | ENT surgery, infectious disease[1] |

| Symptoms | Early: Fever, neck pain[1] Later: Pneumonia, pleural empyema, sepsis, brain abscess, septic emboli[1][2] |

| Complications | Septic shock, end organ failure[2] |

| Usual onset | 10 to 35 years old[2] |

| Causes | Throat infection due to Fusobacterium necrophorum[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, medical imaging[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Throat infection, mononucleosis[2] |

| Treatment | Antibiotics, anticoagulation, surgery[3][1] |

| Frequency | 1 to 6 per million people per year[1][3] |

Lemierre syndrome is infectious thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein.[2][4] Initial symptoms include fever, neck pain, and neck swelling.[1][2] Generally the pain and swelling is one sided and occurs at the angle of the jaw.[2] Later symptoms may include pneumonia, pleural empyema, sepsis, brain abscess, and septic emboli.[1][2] Complications may include septic shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and end organ failure.[2]

It most commonly occurs follow a throat infection due to the bacteria Fusobacterium necrophorum.[3] Other bacteria that may be involved include Fusobacterium nucleatum, streptococci, staphylococci, and Klebsiella pneumoniae.[1] The underlying mechanism involves spread of infection to the lateral pharyngeal space.[2] Diagnosis is generally based on symptoms and ultrasound or CT scan; as culture results take around a week.[1]

Treatment is generally with around two weeks of antibiotics by intravenous followed by up to another six weeks of antibiotics by mouth.[3] Other measures include anticoagulation and surgery to drain any abscesses.[3][1] With treatment, the risk of death is 5 to 18%.[2] Before the availability of antibiotics, the risk of death was 90% over about 2 weeks.[3][1]

Lemierre's syndrome occurs in 1 to 6 per million people per year.[1][3] Young adults males are most commonly affected.[1] In 1936, André Lemierre described 20 cases where throat infections was followed by sepsis.[5][2]

Signs and symptoms

.jpg.webp)

Symptoms of Lemierre's syndrome vary, but usually start with a sore throat, fever, and general body weakness. These are followed by extreme lethargy, spiked fevers, rigors, swollen cervical lymph nodes, and a swollen, tender or painful neck. Often there is abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea and vomiting during this phase. These signs and symptoms usually occur several days to two weeks after the initial symptoms. Symptoms of pulmonary involvement can be shortness of breath, cough and painful breathing (pleuritic chest pain). Rarely, blood is coughed up. Painful or inflamed joints can occur when the joints are involved.

Septic shock can also arise. This presents with low blood pressure, increased heart rate, decreased urine output and an increased rate of breathing. Some cases will also present with meningitis, which will typically manifest as neck stiffness, headache and sensitivity of the eyes to light. Liver enlargement and spleen enlargement can be found, but are not always associated with liver or spleen abscesses.[6][7] Other symptoms may include:

- Headache (unrelated to meningitis)

- Memory loss

- Muscle pain

- Jaundice

- Decreased ability to open the jaw

- Crepitations are sometimes heard over the lungs

- Pericardial friction rubs as a sign of pericarditis (rare)

- Cranial nerve paralysis and Horner's syndrome (both rare)

Cause

The bacteria causing the thrombophlebitis are anaerobic bacteria that are typically normal components of the microorganisms that inhabit the mouth and throat. Species of Fusobacterium, specifically Fusobacterium necrophorum, are most commonly the causative bacteria, but various bacteria have been implicated. One 1989 study found that 81% of Lemierres's syndrome had been infected with Fusobacterium necrophorum, while 11% were caused by other Fusobacterium species.[8] MRSA might also be an issue in Lemierre infections.[9] Rarely Lemierre's syndrome is caused by other (usually Gram-negative) bacteria, which include Bacteroides fragilis and Bacteroides melaninogenicus, Peptostreptococcus spp., Streptococcus microaerophile, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Eikenella corrodens.[8][10]

Pathophysiology

Lemierre's syndrome begins with an infection of the head and neck region, with most primary sources of infection in the palatine tonsils and peritonsillar tissue.[11] Usually this infection is a pharyngitis (which occurred in 87.1% of patients as reported by a literature review[7]), and can be preceded by infectious mononucleosis as reported in several cases.[11] It can also be initiated by infections of the ear, mastoid bone, sinuses, or saliva glands.

During the primary infection, F. necrophorum colonizes the infection site and the infection spreads to the parapharyngeal space. The bacteria then invade the peritonsillar blood vessels where they can spread to the internal jugular vein.[6] In this vein, the bacteria cause the formation of a thrombus containing these bacteria. Furthermore, the internal jugular vein becomes inflamed. This septic thrombophlebitis can give rise to septic microemboli[12] that disseminate to other parts of the body where they can form abscesses and septic infarctions. The first capillaries that the emboli encounter where they can nestle themselves are the pulmonary capillaries. As a consequence, the most frequently involved site of septic metastases are the lungs, followed by the joints (knee, hip, sternoclavicular joint, shoulder and elbow[13]). In the lungs, the bacteria cause abscesses, nodulary and cavitary lesions. Pleural effusion is often present.[7] Other sites involved in septic metastasis and abscess formation are the muscles and soft tissues, liver, spleen, kidneys and nervous system (intracranial abscesses, meningitis).[6]

Production of bacterial toxins such as lipopolysaccharide leads to secretion of cytokines by white blood cells which then both lead to symptoms of sepsis. F. necrophorum produces hemagglutinin which causes platelet aggregation that can lead to diffuse intravascular coagulation and thrombocytopenia.[14][15]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis and the imaging (and laboratory) studies to be ordered largely depend on the patient history, signs and symptoms. If a persistent sore throat with signs of sepsis are found, physicians are cautioned to screen for Lemierre's syndrome.

Laboratory investigations reveal signs of a bacterial infection with elevated C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and white blood cells (notably neutrophils). Platelet count can be low or high. Liver and kidney function tests are often abnormal.

Thrombosis of the internal jugular vein can be displayed with sonography. Thrombi that have developed recently have low echogenicity or echogenicity similar to the flowing blood, and in such cases pressure with the ultrasound probe show a non-compressible jugular vein - a sure sign of thrombosis. Also color or power Doppler ultrasound identify a low echogenicity blood clot. A CT scan or an MRI scan is more sensitive in displaying the thrombus of the intra-thoracic retrosternal veins, but are rarely needed.

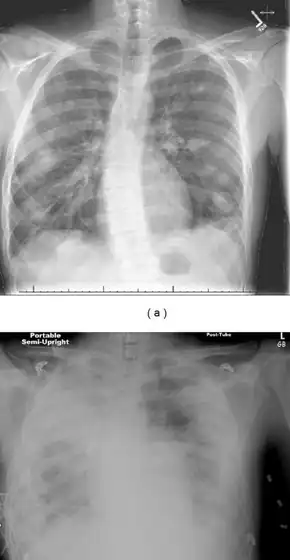

Chest X-ray and chest CT may show pleural effusion, nodules, infiltrates, abscesses and cavitations.

Bacterial cultures taken from the blood, joint aspirates or other sites can identify the causative agent of the disease.

Differential diagnosis

Other illnesses that can appear similar include:

Treatment

Lemierre's syndrome is primarily treated with antibiotics given intravenously. Fusobacterium necrophorum is generally highly susceptible to beta-lactam antibiotics, metronidazole, clindamycin and third generation cephalosporins while the other fusobacteria have varying degrees of resistance to beta-lactams and clindamycin.[15] Additionally, there may exist a co-infection by another bacterium. For these reasons is often advised not to use monotherapy in treating Lemierre's syndrome. Penicillin and penicillin-derived antibiotics can thus be combined with a beta-lactamase inhibitor such as clavulanic acid or with metronidazole.[6][10] Clindamycin can be given as monotherapy.

If antibiotic therapy is unsuccessful, additional treatments include draining of any abscesses and ligation of the internal jugular vein where the antibiotic cannot penetrate.[7][10][16] There is no evidence to opt for or against the use of anticoagulation therapy. The low incidence of Lemierre's syndrome has not made it possible to set up clinical trials to study the disease.[10]

Prognosis

The mortality rate was 90% prior to antibiotic therapy. In the contemporary era, a mortality of 4% has been estimated.[17] Since this disease is not well known and often remains undiagnosed, mortality might be much higher. Approximately 10% of those with the condition experience clinical sequelae, including cranial nerve palsy and orthopaedic limitations.[17]

Epidemiology

Lemierre's syndrome is currently rare, but was more common in the early 20th century before the discovery of penicillin. The reduced use of antibiotics for sore throats may have increased the risk of this disease, with 19 cases in 1997 and 34 cases in 1999 reported in the UK.[18] The estimated incidence rate is 0.8 to 3.6 cases per million in the general population, but is higher in healthy young adults. The number of cases reported is increasing; however, because of its rarity, physicians may be unaware of its existence, possibly leading to underdiagnosis.[19]

History

Sepsis following from a throat infection was described by Hugo Schottmüller in 1918.[20] In 1936, André Lemierre published a series of 20 cases where throat infections were followed by identified anaerobic sepsis, of whom 18 patients died.[5]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Lee, WS; Jean, SS; Chen, FL; Hsieh, SM; Hsueh, PR (August 2020). "Lemierre's syndrome: A forgotten and re-emerging infection". Journal of microbiology, immunology, and infection = Wei mian yu gan ran za zhi. 53 (4): 513–517. doi:10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.027. PMID 32303484.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Allen, BW; Anjum, F; Bentley, TP (January 2022). "Lemierre Syndrome". PMID 29763021.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Welkoborsky, Hans J.; Jecker, Peter (1 July 2019). Ultrasonography of the Head and Neck: An Imaging Atlas. Springer. p. 222. ISBN 978-3-030-12641-4. Archived from the original on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ↑ "Lemierre syndrome" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- 1 2 Lemierre A (1936). "On certain septicemias due to anaerobic organisms". Lancet. 1 (5874): 701–3. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)57035-4.

- 1 2 3 4 Syed MI, Baring D, Addidle M, Murray C, Adams C (September 2007). "Lemierre syndrome: two cases and a review". The Laryngoscope. 117 (9): 1605–1610. doi:10.1097/MLG.0b013e318093ee0e. PMID 17762792. S2CID 12675030.

- 1 2 3 4 Chirinos JA, Lichtstein DM, Garcia J, Tamariz LJ (November 2002). "The evolution of Lemierre syndrome: report of 2 cases and review of the literature". Medicine (Baltimore). 81 (6): 458–465. doi:10.1097/00005792-200211000-00006. PMID 12441902. S2CID 28941739.

- ↑ NCBI PubMed; Bentley TP; Brennan DF (August 2009). "Lemierre's syndrome: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) finds a new home". Medicine (Orlando). 37 (2): 131–4. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.07.066. PMID 18280087.

- 1 2 3 4 Puymirat E, Biais M, Camou F, Lefèvre J, Guisset O, Gabinski C (March 2008). "A Lemierre's syndrome variant caused by Staphylococcus aureus". American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 26 (3): 380–387. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2007.05.020. PMID 18358967.

- 1 2 Eilbert, Wesley; Singla, Nitin (2013-10-23). "Lemierre's syndrome". International Journal of Emergency Medicine. 6 (1): 40. doi:10.1186/1865-1380-6-40. ISSN 1865-1380. PMC 4015694. PMID 24152679.

- ↑ Screaton NJ, Ravenel JG, Lehner PJ, Heitzman ER, Flower CD (November 1999). "Lemierre Syndrome: Forgotten but Not Extinct-Report of Four Cases". Radiology. 213 (2): 369–374. doi:10.1148/radiology.213.2.r99nv09369. PMID 10551214. Archived from the original on 2009-06-12. Retrieved 2022-08-19.

The absence of proximal thrombus at CT pulmonary angiography suggests that microemboli, rather than the macroembolic clot burden more typical of acute pulmonary embolism, are responsible for the pulmonary findings in Lemierre syndrome

- ↑ Beldman TF, Teunisse HA, Schouten TJ (November 1997). "Septic arthritis of the hip by Fusobacterium necrophorum after tonsillectomy: a form of Lemierre syndrome?". European Journal of Pediatrics. 156 (11): 856–857. doi:10.1007/s004310050730. PMID 9392400. S2CID 30745447.

- ↑ Kanoe M, Yamanaka M, Inoue M (1989). "Effects of Fusobacterium necrophorum on the mesenteric microcirculation of guinea pigs". Medical Microbiology and Immunology. 178 (2): 99–104. doi:10.1007/bf00203305. PMID 2659950. S2CID 35453227.

- 1 2 Hagelskjaer Kristensen L, Prag J (Aug 2000). "Human necrobacillosis, with emphasis on Lemierre's syndrome". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 31 (2): 524–532. doi:10.1086/313970. PMID 10987717.

- ↑ Aspesberro F, Siebler T, Van Nieuwenhuyse JP, Panosetti E, Berthet F (September 2008). "Lemierre syndrome in a 5-month-old male infant: Case report and review of the pediatric literature". Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 9 (5): e35–7. doi:10.1097/PCC.0b013e31817319fa. PMID 18779698. S2CID 52858512.

- 1 2 Valerio, Luca; Zane, Federica (2020). "Patients with Lemierre syndrome have a high risk of new thromboembolic complications, clinical sequelae, and death: an analysis of 712 cases". Journal of Internal Medicine. 289 (3): 325–339. doi:10.1111/joim.13114. PMID 32445216.

- ↑ UK Chief Medical Officer Update 29 February 2001 (CMO Update29 Feb 2001 Archived 11 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine)

- ↑ Valerio, Luca; Corsi, Gabriele (2020). "Lemierre syndrome: Current evidence and rationale of the Bacteria-Associated Thrombosis, Thrombophlebitis and LEmierre syndrome (BATTLE) registry". Thrombosis Research. 196: 494–499. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2020.10.002. PMID 33091703.

- ↑ Schottmuller H (1918). "Ueber die Pathogenität anaërober Bazillen". Dtsch Med Wochenschr (in Deutsch). 44: 1440.

External links

| Classification |

|

|---|---|

| External resources |

|