Peptostreptococcus

| Peptostreptococcus | |

|---|---|

| |

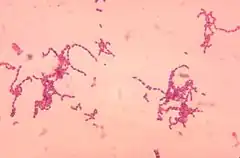

| Peptostreptococcus spp. growing in characteristic chain formations. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Peptostreptococcus |

| Species | |

|

Peptostreptococcus anaerobius | |

Peptostreptococcus is a genus of anaerobic, Gram-positive, non-spore forming bacteria. The cells are small, spherical, and can occur in short chains, in pairs or individually. They typically move using cilia.[2] Peptostreptococcus are slow-growing bacteria with increasing resistance to antimicrobial drugs.[3] Peptostreptococcus is a normal inhabitant of the healthy lower reproductive tract of women.[4][5]

Pathogenesis

Peptostreptococcus species are commensal organisms in humans, living predominantly in the mouth, skin, gastrointestinal, vagina and urinary tracts, and are members of the gut microbiota. Under immunosuppressed or traumatic conditions these organisms can become pathogenic, as well as septicemic, harming their host. Peptostreptococcus can cause brain, liver, breast, and lung abscesses, as well as generalized necrotizing soft tissue infections. They participate in mixed anaerobic infections, a term which is used to describe infections that are caused by multiple bacteria that do not require or may even be harmed by oxygen.[6]

Peptostreptococcus species are susceptible to beta-lactam antibiotics.[7]

They are isolated with high frequency from all specimen sources. Anaerobic gram-positive cocci such as Peptostreptococcus are the second most frequently recovered anaerobes and account for approximately one quarter of anaerobic isolates found. Most often Anaerobic gram-positive cocci are usually recovered mixed in with other anaerobic or aerobic bacteria from various infections at different sites of the human body. This contributes to the difficulty of isolating Peptostreptococcus organisms.[8]

Infections

Peptostreptococcus species that are found in clinical infections were once part of the genus formerly known as Peptococcus. Peptostreptococcus is the only genus among anaerobic gram-positive cocci that is encountered in clinical infections. As such, Peptostreptococcus species are viewed as being clinically significant anaerobic cocci. Other similar clinically significant anaerobic cocci include Veillonella species (gram-negative cocci), and microaerophilic streptococci (aerotolerant). Anaerobic gram-positive cocci include various clinically significant species of the genus Peptostreptococcus.[9]

One clinically significant Peptostreptococcus species is Peptostreptococcus tetradius (formerly Gaffkya anaerobia). The species of anaerobic gram-positive cocci isolated most commonly include Peptostreptococcus magnus, Peptostreptococcus asaccharolyticus, Peptostreptococcus anaerobius, Peptostreptococcus prevotii, and Peptostreptococcus micros.

Anaerobic gram-positive cocci that produce large amounts of lactic acid during the process of carbohydrate fermentation were reclassified as Streptococcus parvulus and Streptococcus morbillorum from Peptococcus or Peptostreptococcus. Most of these organisms are anaerobic, but some are microaerophilic.

Due to a large amount of new research done on the human microbe and more information on bacteria, many species of bacteria have been renamed and re-classified. Based on DNA homology and whole-cell polypeptide-pattern study findings supported by phenotypic characteristics, the DNA homology group of microaerobic streptococci that was formerly known as Streptococcus anginosus or Streptococcus milleri is now composed of three distinct species: S anginosus, Streptococcus constellatus, and Streptococcus intermedius. The microaerobic species S morbillorum was transferred into the genus Gemella. A new species within the genus Peptostreptococcus is Peptostreptococcus hydrogenalis; it contains the indole-positive, saccharolytic strains of the genus.[10]

Peptostreptococcus infections occur in/on all body sites, including the CNS, head, neck, chest, abdomen, pelvis, skin, bone, joint, and soft tissues. Adequate therapy must be taken against infections, or it could result in clinical failures. Peptostreptoccocci are often overlooked and they are very difficult to isolate, appropriate specimen collection is required. Peptostreptococci grow slowly which makes them increasingly resistant to antimicrobrials.[9]

The most common Peptostreptococcus species found in infections are P. magnus (18% of all anaerobic gram-positive cocci and microaerophilic streptococci), P asaccharolyticus (17%), P anaerobius (16%), P prevotii (13%), P micros (4%), Peptostreptococcus saccharolyticus (3%), and Peptostreptococcus intermedius (2%).[11]

P magnus were highly recovered in bone and chest infections. P asaccharolyticus and P anaerobius and the highest recovery rate in obstetrical/gynecological and respiratory tract infections and wounds. When anaerobic and facultative cocci were recovered most of the infection were polymicrobial. Most patients from whom microaerophilic streptococci were recovered in pure culture had abscesses (e.g., dental, intracranial, pulmonary), bacteremia, meningitis, or conjunctivitis. P. Magnus is the most commonly isolated anaerobic cocci and is often recovered in pure culture. Other common Peptostreptococci in the different infectious sites are P anaerobius which occurs in oral infections; P micros in respiratory tract infection.s, P magnus, P micros, P asaccharolyticus, Peptostreptococcus vaginalis, and P anaerobius in skin and soft tissue infections; P magnus and P micros in deep organ abscesses; P magnus, P micros, and P anaerobius in gastrointestinal tract–associated infections; P magnus, P micros, P asaccharolyticus, P vaginalis, P tetradius, and P anaerobius in female genitourinary infections; and P magnus, P asaccharolyticus, P vaginalis, and P anaerobius in bone and joint infections and leg and foot ulcers.[12]

Many infections caused by peptostreptococcus bacteria are synergistic. Bacterial synergy, the presence of which is determined by mutual induction of sepsis enhancement, increased mortality, increased abscess inducement, and enhancement of the growth of the bacterial components in mixed infections, is found between anaerobic gram-positive cocci and their aerobic and anaerobic counterparts. The ability of anaerobic gram-positive cocci and microaerophilic streptococci to produce capsular material is an important virulence mechanism, but other factors may also influence the interaction of these organisms in mixed infections.[13]

Although anaerobic cocci can be isolated from infections at all body sites, a predisposition for certain sites has been observed. In general, Peptostreptococcus species, particularly P magnus, have been recovered more often from subcutaneous and soft tissue abscesses and diabetes-related foot ulcers than from intra-abdominal infections. Peptostreptococcus infections occur more often in chronic infections.[9]

Frequency of infections

It is difficult to determine the exact frequency of peptostreptococcus infections because of inappropriate collection methods, transportation, and specimen cultivation. Peptostreptococcus infections are most commonly found in patients who have had or have chronic infections. Patients who have predisposing conditions are shown to have 5% higher recovery rate of the bacteria in blood cultures.[14]

Of all anaerobic bacteria recovered at hospitals from 1973 to 1985, anaerobic gram-positive cocci accounted for 26% of it. The infected sited where these organisms were found in the greatest abundance were obstetrical and gynecological sites (35%), bones (39%) cysts (40%), and ears (53%). Occasionally found in other places such as abdomen, lymph nodes, bile, and eyes.[14]

Frequency of infections is greater in developing countries because treatment is often slow, or it is impossible to get the adequate treatment, but mortality due to peptostreptococcus infections have decreased in the last 30 years and will continue to do so due to better treatment.

All ages are susceptible to peptostreptococcus infections, however children are more likely to get head and neck infections.

Infection types

Skin and soft tissue infections

Anaerobic gram-positive cocci and microaerophilic streptococci are often recovered in polymicrobial skin and soft tissue infections, such as gangrene, fasciitis, ulcers, diabetes-related foot infections, burns, human or animal bites, infected cysts, abscesses of the breast, rectum, and anus. Anaerobic gram-positive cocci and microaerophilic streptococci are generally found mixed with other aerobic and anaerobic bacteria that originate from the mucosal surface adjacent to the infected site or that have been inoculated into the infected site.

Peptostreptococcus spp. can cause infections such as gluteal decubitus ulcers, diabetes-related foot infections, and rectal abscesses. Anaerobic gram-positive cocci and microaerophilic streptococci are part of the normal skin microbiota, so it is hard to avoid contamination by these bacteria when obtaining specimens.[8][9]

CNS infections

CNS infections can be isolated from subdural empyema and brain abscesses which are a result of chronic infections. Also isolated from sinuses, teeth and mastoid. 46% of 39 brain abscesses in one study showed anaerobic gram-positive cocci and microaerophilic streptococci.[8][9]

Upper respiratory tract and dental infections

There is a high rate of anaerobic cocci colonization which accounts for the organisms significance in these infections. Anaerboci gram-positive cocci and micraerophilic streptococci are often recovered in these infections. They have been recovered in 15% of patients with chronic mastoiditis. When Peptostreptococci and other anaerobes predominate, aggressive treatment of acute infection can prevent chronic infection. When the risk of anaerobic infection is high, as with intra-abdominal and post-surgical infections, proper antimicrobial prophylaxis may reduce the risk 90% of the time, other organisms were mixed in with the anaerobic gram-positive cocci and microaerophilic streptococci. This includes streptococcus species, and staphylococcus aureus.[8][9] Peptostreptococcus micros has a moderate association with periodontal disease.

Bacteremia and endocarditis

Peptostreptococci can cause fatal endocarditis, paravalvular abscess, and pericarditis. The most frequent source of bacteremia due to Peptostreptococcus are infections of the oropharynx, lower respiratory tract, female genital tract, abdomen, skin, and soft tissues. Recent gynecological surgery, immunosuppression, dental procedures, infections of the female genital tract, abdominal and soft tissue along with gastrointestinal surgery are predisposing factors for bacteremia due to peptostreptococcus.

Microaerophilic streptococci typically account for 5-10% of cases of endocarditis; however, Peptostreptococci have only rarely been isolated.[8][9]

Anaerobic pleuropulmonary infections

Anaerobic gram-positive cocci and microaerophilic streptococci are most frequently found in aspiration pneumonia, empyema, lung abscesses, and mediastinitis. These bacteria account for 10-20% of anaerobic isolated recovered from pulmonary infections. It is difficult to obtain appropriate culture specimens. It requires a direct lung puncture, or the use of trans-tracheal aspiration.[8][9]

Abdominal infections

Anaerobic gram-positive cocci are part of the normal gastrointestinal microbiota. They are isolated in approximately 20% of specimens from intra-abdominal infections, such as peritonitis. Found in abscesses of the liver, spleen, and abdomen. Like in upper respiratory tract and dental infections, anaerobic gram-positive cocci are recovered mixed with other bacteria. In this case they are mixed with organisms of intestinal origin such as E coli, bacteroides fragilis group, and clostridium species.[8][9]

Female pelvic infections

Anaerobic gram-positive cocci are frequently isolated from anaerobically infected bones and joints., they accounted for 40% of anaerobic isolates of osteomyelitis caused by anaerobic bacteria and 20% of anaerobic isolates of arthritis caused by anaerobic bacteria. P magnus and P prevotii are the predominant bone and joint isolates. Management of these infections requires prolonged courses of antimicrobials and is enhanced by removal of the foreign material.[8][9]

Peptostreptococcus species are part of the microbiota of the lower reproductive tract of women.[4][5]

Causes of infection

Infections with anaerobic gram-positive cocci and microaerophilic streptococci are often caused by:

- Trauma

- Immunodeficiency

- Steroid therapy

- Vascular disease

- Malignancy

- Reduced blood supply

- Previous surgery

- Presence of a foreign body

- Sickle cell anemia

- Diabetes

Treatment

When Peptostreptococci and other anaerobes predominate, aggressive treatment of acute infection can prevent chronic infection. When the risk of anaerobic infection is high, as with intra-abdominal and post-surgical infections, proper antimicrobial prophylaxis may reduce the risk. Therapy with antimicrobials (e.g., aminoglycosides, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, older quinolones) often does not eradicate anaerobes.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Parte, A.C. "Peptostreptococcus". LPSN.

- ↑ Ryan KJ; Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- ↑ Higaki S, Kitagawa T, Kagoura M, Morohashi M, Yamagishi T (2000). "Characterization of Peptostreptococcus species in skin infections". J Int Med Res. 28 (3): 143–7. doi:10.1177/147323000002800305. PMID 10983864. S2CID 30682359.

- 1 2 Hoffman, Barbara (2012). Williams gynecology (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 65. ISBN 978-0071716727.

- 1 2 Senok, Abiola C; Verstraelen, Hans; Temmerman, Marleen; Botta, Giuseppe A; Senok, Abiola C (2009). "Probiotics for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD006289. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006289.pub2. PMID 19821358.

- ↑ Mader JT, Calhoun J (1996). Baron S, et al. (eds.). Bone, Joint, and Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infections. In: Baron's Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1. (via NCBI Bookshelf).

- ↑ Brook I. Treatment of anaerobic infection. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2007; 5:991-1006

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Finegold SM. Anaerobic Bacteria in Human Disease. Orlando, Fla: Academic Press; 1977.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Brook I. Anaerobic Infections. In: Diagnosis and Management. 4th Edition. New York: Informa Healthcare USA Inc.; 2007.

- ↑ Brook I. Recovery of anaerobic bacteria from clinical specimens in 12 years at two military hospitals. J Clin Microbiol. Jun 1988;26(6):1181-8. [Medline].

- ↑ Bourgault AM, Rosenblatt JE, Fitzgerald RH. Peptococcus magnus: a significant human pathogen. Ann Intern Med. Aug 1980;93(2):244-8. [Medline].

- ↑ Brook I. Peptostreptococcal infection in children. Scand J Infect Dis. 1994;26(5):503-10. [Medline].

- ↑ Araki H, Kuriyama T, Nakagawa K, Karasawa T. The microbial synergy of Peptostreptococcus micros and Prevotella intermedia in a urine abscess model. Oral Microbiol Immunol. Jun 2004;19(3):177-81. [Medline].

- 1 2 Martin WJ. Isolation and identification of anaerobic bacteria in the clinical laboratory. A 2-year experience. Mayo Clin Proc. May 1974;49(5):300-8. [Medline].

External links

- Peptostreptococcus infections from eMedicine.