Infectious mononucleosis

| Infectious mononucleosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Glandular fever, Pfeiffer's disease, Filatov's disease,[1] kissing disease | |

| |

| Swollen lymph nodes in the neck of a person with infectious mononucleosis | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

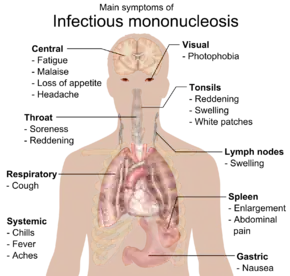

| Symptoms | Fever, sore throat, enlarged lymph nodes in the neck, tiredness[2] |

| Complications | Swelling of the liver or spleen[3] |

| Duration | 2–4 weeks[2] |

| Causes | Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) usually spread via saliva[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms and blood tests[3] |

| Treatment | Drinking enough fluids, getting sufficient rest, pain medications such as paracetamol (acetaminophen) and ibuprofen[2][4] |

| Frequency | 45 per 100,000 per year (USA)[5] |

Infectious mononucleosis (IM, mono), also known as glandular fever, is an infection usually caused by the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV).[2][3] Most people are infected by the virus as children, when the disease produces few or no symptoms.[2] In young adults, the disease often results in fever, sore throat, enlarged lymph nodes in the neck, and tiredness.[2] Most people recover in two to four weeks; however, feeling tired may last for months.[2] The liver or spleen may also become swollen,[3] and in less than one percent of cases splenic rupture may occur.[6]

While usually caused by Epstein–Barr virus, also known as human herpesvirus 4, which is a member of the herpesvirus family,[3] a few other viruses may also cause the disease.[3] It is primarily spread through saliva but can rarely be spread through semen or blood.[2] Spread may occur by objects such as drinking glasses or toothbrushes or through a cough or sneeze.[2][7] Those who are infected can spread the disease weeks before symptoms develop.[2] Mono is primarily diagnosed based on the symptoms and can be confirmed with blood tests for specific antibodies.[3] Another typical finding is increased blood lymphocytes of which more than 10% are atypical.[3][8] The monospot test is not recommended for general use due to poor accuracy.[9]

There is no vaccine for EBV, but infection can be prevented by not sharing personal items or saliva with an infected person.[2] Mono generally improves without any specific treatment.[2] Symptoms may be reduced by drinking enough fluids, getting sufficient rest, and taking pain medications such as paracetamol (acetaminophen) and ibuprofen.[2][4]

Mono most commonly affects those between the ages of 15 to 24 years in the developed world.[8] In the developing world, people are more often infected in early childhood when there are fewer symptoms.[10] In those between 16 and 20 it is the cause of about 8% of sore throats.[8] About 45 out of 100,000 people develop infectious mono each year in the United States.[5] Nearly 95% of people have had an EBV infection by the time they are adults.[5] The disease occurs equally at all times of the year.[8] Mononucleosis was first described in the 1920s and colloquially known as "the kissing disease".[11]

Signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of infectious mononucleosis vary with age.

Children

Before puberty, the disease typically only produces flu-like symptoms, if any at all. When found, symptoms tend to be similar to those of common throat infections (mild pharyngitis, with or without tonsillitis).[13]

Adolescents and young adults

In adolescence and young adulthood, the disease presents with a characteristic triad:[14]

- Fever – usually lasting 14 days;[15] often mild[13]

- Sore throat – usually severe for 3–5 days, before resolving in the next 7–10 days.[16]

- Swollen glands – mobile; usually located around the back of the neck (posterior cervical lymph nodes) and sometimes throughout the body.[8][13][17]

Another major symptom is feeling tired.[2] Headaches are common, and abdominal pains with nausea or vomiting sometimes also occur.[14] Symptoms most often disappear after about 2–4 weeks.[2][18] However, fatigue and a general feeling of being unwell (malaise) may sometimes last for months.[13] Fatigue lasts more than one month in an estimated 28% of cases.[19] Mild fever, swollen neck glands and body aches may also persist beyond 4 weeks.[13][20][21] Most people are able to resume their usual activities within 2–3 months.[20]

The most prominent sign of the disease is often the pharyngitis, which is frequently accompanied by enlarged tonsils with pus—an exudate similar to that seen in cases of strep throat.[13] In about 50% of cases, small reddish-purple spots called petechiae can be seen on the roof of the mouth.[21] Palatal enanthem can also occur, but is relatively uncommon.[13]

A small minority of people spontaneously present a rash, usually on the arms or trunk, which can be macular (morbilliform) or papular.[13] Almost all people given amoxicillin or ampicillin eventually develop a generalized, itchy maculopapular rash, which however does not imply that the person will have adverse reactions to penicillins again in the future.[13][18] Occasional cases of erythema nodosum and erythema multiforme have been reported.[13] Seizures may also occasionally occur.[22]

Complications

Spleen enlargement is common in the second and third weeks, although this may not be apparent on physical examination. Rarely the spleen may rupture. There may also be some enlargement of the liver.[21] Jaundice occurs only occasionally.[13][23]

It generally gets better on its own in people who are otherwise healthy.[24] When caused by EBV, infectious mononucleosis is classified as one of the Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative diseases. Occasionally the disease may persist and result in a chronic infection. This may develop into systemic EBV-positive T cell lymphoma.[24]

Older adults

Infectious mononucleosis mainly affects younger adults.[13] When older adults do catch the disease, they less often have characteristic signs and symptoms such as the sore throat and lymphadenopathy.[13][21] Instead, they may primarily experience prolonged fever, fatigue, malaise and body pains.[13] They are more likely to have liver enlargement and jaundice.[21] People over 40 years of age are more likely to develop serious illness.[25] (See Prognosis.)

Incubation period

The exact length of time between infection and symptoms is unclear. A review of the literature made an estimate of 33–49 days.[26] In adolescents and young adults, symptoms are thought to appear around 4–6 weeks after initial infection.[13] Onset is often gradual, though it can be abrupt.[25] The main symptoms may be preceded by 1–2 weeks of fatigue, feeling unwell and body aches.[13]

Cause

Epstein–Barr virus

About 90% of cases of infectious mononucleosis are caused by the Epstein–Barr virus, a member of the Herpesviridae family of DNA viruses. It is one of the most commonly found viruses throughout the world. Contrary to common belief, the Epstein–Barr virus is not highly contagious. It can only be contracted through direct contact with an infected person's saliva, such as through kissing or sharing toothbrushes.[27] About 95% of the population has been exposed to this virus by the age of 40, but only 15–20% of teenagers and about 40% of exposed adults actually become infected.[28]

Cytomegalovirus

A minority of cases of infectious mononucleosis is caused by human cytomegalovirus (CMV), another type of herpes virus. This virus is found in body fluids including saliva, urine, blood, and tears.[29] A person becomes infected with this virus by direct contact with infected body fluids. Cytomegalovirus is most commonly transmitted through kissing and sexual intercourse. It can also be transferred from an infected mother to her unborn child. This virus is often "silent" because the signs and symptoms cannot be felt by the person infected.[29] However, it can cause life-threatening illness in infants, people with HIV, transplant recipients, and those with weak immune systems. For those with weak immune systems, cytomegalovirus can cause more serious illnesses such as pneumonia and inflammations of the retina, esophagus, liver, large intestine, and brain. Approximately 90% of the human population has been infected with cytomegalovirus by the time they reach adulthood, but most are unaware of the infection.[30] Once a person becomes infected with cytomegalovirus, the virus stays in his/her body fluids throughout the person's lifetime.

Transmission

Epstein–Barr virus infection is spread via saliva, and has an incubation period of four to seven weeks.[31] The length of time that an individual remains contagious is unclear, but the chances of passing the illness to someone else may be the highest during the first six weeks following infection. Some studies indicate that a person can spread the infection for many months, possibly up to a year and a half.[32]

Pathophysiology

The virus replicates first within epithelial cells in the pharynx (which causes pharyngitis, or sore throat), and later primarily within B cells (which are invaded via their CD21). The host immune response involves cytotoxic (CD8-positive) T cells against infected B lymphocytes, resulting in enlarged, atypical lymphocytes (Downey cells).[33]

When the infection is acute (recent onset, instead of chronic), heterophile antibodies are produced.[21]

Cytomegalovirus, adenovirus and Toxoplasma gondii (toxoplasmosis) infections can cause symptoms similar to infectious mononucleosis, but a heterophile antibody test will test negative and differentiate those infections from infectious mononucleosis.[2][34]

Mononucleosis is sometimes accompanied by secondary cold agglutinin disease, an autoimmune disease in which abnormal circulating antibodies directed against red blood cells can lead to a form of autoimmune hemolytic anemia. The cold agglutinin detected is of anti-i specificity.[35][36]

Diagnosis

Diagnostic for infectious mononucleosis may be partly based on:

- Person's age, with highest risk at 10 to 30 years.[21]

- Medical history, such as close contact with other people with infectious mononucleosis, and the presence and time of onset of "mononucleosis-like symptoms" such as fever and sore throat.

- Physical examination, including enlarged lymph nodes in the neck, or enlarged spleen.[37]

- The heterophile antibody test is a screening test that gives results within a day,[38] but has less than full sensitivity (70–92%) in the first two weeks after symptoms begin.[21][39]

- Serological tests take longer time than the heterophile antibody test, but are more accurate.

The most useful tests are a high lymphocyte count and atypical lymphocytes.[40]

Physical examination

The presence of an enlarged spleen, and swollen posterior cervical, axillary, and inguinal lymph nodes are the most useful to suspect a diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis. On the other hand, the absence of swollen cervical lymph nodes and fatigue are the most useful to dismiss the idea of infectious mononucleosis as the correct diagnosis. The insensitivity of the physical examination in detecting an enlarged spleen means it should not be used as evidence against infectious mononucleosis.[21] A physical examination may also show petechiae in the palate.[21]

Heterophile antibody test

The heterophile antibody test, or monospot test, works by agglutination of red blood cells from guinea pig, sheep and horse. This test is specific but not particularly sensitive (with a false-negative rate of as high as 25% in the first week, 5–10% in the second, and 5% in the third).[21] About 90% of diagnosed people have heterophile antibodies by week 3, disappearing in under a year. The antibodies involved in the test do not interact with the Epstein–Barr virus or any of its antigens.[41]

The monospot test is not recommended for general use by the CDC due to its poor accuracy.[9]

Serology

Serologic tests detect antibodies directed against the Epstein–Barr virus. Immunoglobulin G (IgG), when positive, mainly reflects a past infection, whereas immunoglobulin M (IgM) mainly reflects a current infection. EBV-targeting antibodies can also be classified according to which part of the virus they bind to:

- Viral capsid antigen (VCA):

- Early antigen (EA)

- Anti-EA IgG appears in the acute phase of illness and disappears after 3 to 6 months. It is associated with having an active infection. Yet, 20% of people may have antibodies against EA for years despite having no other sign of infection.[9]

- EBV nuclear antigen (EBNA)

- Antibody to EBNA slowly appears 2 to 4 months after onset of symptoms and persists for the rest of a person’s life.[9]

When negative, these tests are more accurate than the heterophile antibody test in ruling out infectious mononucleosis. When positive, they feature similar specificity to the heterophile antibody test. Therefore, these tests are useful for diagnosing infectious mononucleosis in people with highly suggestive symptoms and a negative heterophile antibody test.

Other tests

- Epstein–Barr nuclear antigen detection. While it is not normally recognizable until several weeks into the disease, and is useful for distinguishing between a recent-onset of infectious mononucleosis and symptoms caused by a previous infection.

- Elevated hepatic transaminase levels is highly suggestive of infectious mononucleosis, occurring in up to 50% of people.[21]

- By blood film, one diagnostic criterion for infectious mononucleosis is the presence of 50% lymphocytes with at least 10% atypical lymphocytes (large, irregular nuclei),[41] while the person also has fever, pharyngitis, and swollen lymph nodes. The atypical lymphocytes resembled monocytes when they were first discovered, thus the term "mononucleosis" was coined.

- A fibrin ring granuloma may be present.

Differential diagnosis

About 10% of people who present a clinical picture of infectious mononucleosis do not have an acute Epstein–Barr-virus infection.[42] A differential diagnosis of acute infectious mononucleosis needs to take into consideration acute cytomegalovirus infection and Toxoplasma gondii infections. Because their management is much the same, it is not always helpful, or possible, to distinguish between Epstein–Barr-virus mononucleosis and cytomegalovirus infection. However, in pregnant women, differentiation of mononucleosis from toxoplasmosis is important, since it is associated with significant consequences for the fetus.

Acute HIV infection can mimic signs similar to those of infectious mononucleosis, and tests should be performed for pregnant women for the same reason as toxoplasmosis.[21]

People with infectious mononucleosis are sometimes misdiagnosed with a streptococcal pharyngitis (because of the symptoms of fever, pharyngitis and adenopathy) and are given antibiotics such as ampicillin or amoxicillin as treatment.

Other conditions from which to distinguish infectious mononucleosis include leukemia, tonsillitis, diphtheria, common cold and influenza (flu).[41]

Treatment

Infectious mononucleosis is generally self-limiting, so only symptomatic or supportive treatments are used.[43] The need for rest and return to usual activities after the acute phase of the infection may reasonably be based on the person's general energy levels.[21] Nevertheless, in an effort to decrease the risk of splenic rupture experts advise avoidance of contact sports and other heavy physical activity, especially when involving increased abdominal pressure or the Valsalva maneuver (as in rowing or weight training), for at least the first 3–4 weeks of illness or until enlargement of the spleen has resolved, as determined by a treating physician.[21][44]

Medications

Paracetamol (acetaminophen) and NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen, may be used to reduce fever and pain. Prednisone, a corticosteroid, while used to try to reduce throat pain or enlarged tonsils, remains controversial due to the lack of evidence that it is effective and the potential for side effects.[45][46] Intravenous corticosteroids, usually hydrocortisone or dexamethasone, are not recommended for routine use but may be useful if there is a risk of airway obstruction, a very low platelet count, or hemolytic anemia.[47][48]

There is little evidence to support the use of antivirals such as aciclovir and valacyclovir although they may reduce initial viral shedding.[49][50] Although antivirals are not recommended for people with simple infectious mononucleosis, they may be useful (in conjunction with steroids) in the management of severe EBV manifestations, such as EBV meningitis, peripheral neuritis, hepatitis, or hematologic complications.[51]

Although antibiotics exert no antiviral action they may be indicated to treat bacterial secondary infections of the throat,[52] such as with streptococcus (strep throat). However, ampicillin and amoxicillin are not recommended during acute Epstein–Barr virus infection as a diffuse rash may develop.[53]

Observation

Splenomegaly is a common symptom of infectious mononucleosis and health care providers may consider using abdominal ultrasonography to get insight into the enlargement of a person's spleen.[54] However, because spleen size varies greatly, ultrasonography is not a valid technique for assessing spleen enlargement and should not be used in typical circumstances or to make routine decisions about fitness for playing sports.[54]

Prognosis

Serious complications are uncommon, occurring in less than 5% of cases:[55][56]

- CNS complications include meningitis, encephalitis, hemiplegia, Guillain–Barré syndrome, and transverse myelitis. Prior infectious mononucleosis has been linked to the development of multiple sclerosis.[57]

- Hematologic: Hemolytic anemia (direct Coombs test is positive) and various cytopenias, and bleeding (caused by thrombocytopenia) can occur.[35]

- Mild jaundice

- Hepatitis with the Epstein–Barr virus is rare.

- Upper airway obstruction from tonsillar hypertrophy is rare.

- Fulminant disease course of immunocompromised people are rare.

- Splenic rupture is rare.

- Myocarditis and pericarditis are rare.

- Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome

- Chronic fatigue syndrome

- Cancers associated with the Epstein-Barr virus include: Burkitt's lymphoma, Hodgkin's lymphoma and lymphomas in general as well as nasopharyngeal and gastric carcinoma.[58]

Once the acute symptoms of an initial infection disappear, they often do not return. But once infected, the person carries the virus for the rest of their life. The virus typically lives dormantly in B lymphocytes. Independent infections of mononucleosis may be contracted multiple times, regardless of whether the person is already carrying the virus dormantly. Periodically, the virus can reactivate, during which time the person is again infectious, but usually without any symptoms of illness.[2] Usually, a person with IM has few, if any, further symptoms or problems from the latent B lymphocyte infection. However, in susceptible hosts under the appropriate environmental stressors, the virus can reactivate and cause vague physical symptoms (or may be subclinical), and during this phase the virus can spread to others.[2][59][60]

History

The characteristic symptomatology of infectious mononucleosis does not appear to have been reported until the late nineteenth century.[61] In 1885, the renowned Russian pediatrician Nil Filatov reported an infectious process he called "idiopathic adenitis" exhibiting symptoms that correspond to infectious mononucleosis, and in 1889 a German balneologist and pediatrician, Emil Pfeiffer, independently reported similar cases (some of lesser severity) that tended to cluster in families, for which he coined the term Drüsenfieber ("glandular fever").[62][63][64]

The word mononucleosis has several senses.[65] It can refer to any monocytosis (excessive numbers of circulating monocytes),[65] but today it usually is used in its narrower sense of infectious mononucleosis, which is caused by EBV and of which monocytosis is a finding.

The term "infectious mononucleosis" was coined in 1920 by Thomas Peck Sprunt and Frank Alexander Evans in a classic clinical description of the disease published in the Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, entitled "Mononuclear leukocytosis in reaction to acute infection (infectious mononucleosis)".[62][66] A lab test for infectious mononucleosis was developed in 1931 by Yale School of Public Health Professor John Rodman Paul and Walls Willard Bunnell based on their discovery of heterophile antibodies in the sera of persons with the disease.[67] The Paul-Bunnell Test or PBT was later replaced by the heterophile antibody test.

The Epstein–Barr virus was first identified in Burkitt's lymphoma cells by Michael Anthony Epstein and Yvonne Barr at the University of Bristol in 1964. The link with infectious mononucleosis was uncovered in 1967 by Werner and Gertrude Henle at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, after a laboratory technician handling the virus contracted the disease: comparison of serum samples collected from the technician before and after the onset revealed development of antibodies to the virus.[68][69]

Yale School of Public Health epidemiologist Alfred E. Evans confirmed through testing that mononucleosis was transmitted mainly through kissing leading to it being referred to colloquially as "the kissing disease".[70]

References

- ↑ Filatov's disease at Who Named It?

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 "About Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV)". CDC. January 7, 2014. Archived from the original on August 8, 2016. Retrieved Aug 10, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "About Infectious Mononucleosis". CDC. January 7, 2014. Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- 1 2 Ebell, MH (12 April 2016). "JAMA PATIENT PAGE. Infectious Mononucleosis". JAMA. 315 (14): 1532. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.2474. PMID 27115282.

- 1 2 3 Tyring, Stephen; Moore, Angela Yen; Lupi, Omar (2016). Mucocutaneous Manifestations of Viral Diseases: An Illustrated Guide to Diagnosis and Management (2 ed.). CRC Press. p. 123. ISBN 9781420073133. Archived from the original on 2017-09-11.

- ↑ Handin, Robert I.; Lux, Samuel E.; Stossel, Thomas P. (2003). Blood: Principles and Practice of Hematology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 641. ISBN 9780781719933. Archived from the original on 2017-09-11.

- ↑ "Mononucleosis - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ebell, MH; Call, M; Shinholser, J; Gardner, J (12 April 2016). "Does This Patient Have Infectious Mononucleosis?: The Rational Clinical Examination Systematic Review". JAMA. 315 (14): 1502–9. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.2111. PMID 27115266.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Epstein-Barr Virus and Infectious Mononucleosis Laboratory Testing". CDC. January 7, 2014. Archived from the original on 7 August 2016. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- ↑ Marx, John; Walls, Ron; Hockberger, Robert (2013). Rosen's Emergency Medicine - Concepts and Clinical Practice (8 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1731. ISBN 978-1455749874. Archived from the original on 2017-09-11.

- ↑ Smart, Paul (1998). Everything You Need to Know about Mononucleosis. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 11. ISBN 9780823925506.

- ↑ Stöppler, Melissa Conrad (7 September 2011). Shiel, William C. Jr. (ed.). "Infectious Mononucleosis (Mono)". MedicineNet. medicinenet.com. Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Cohen JI (2008). "Epstein-Barr Infections, Including Infectious Mononucleosis". In Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J (eds.). Harrison's principles of internal medicine (17th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division. pp. 380–91. ISBN 978-0-07-146633-2.

- 1 2 Cohen, Jeffrey I. (2005). "Clinical Aspects of Epstein-Barr Infection". In Robertson, Erle S. (ed.). Epstein-Barr Virus. Horizon Scientific Press. pp. 35–42. ISBN 978-1-904455-03-5. Archived from the original on 24 February 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ↑ Cohen, Jonathan; Powderly, William G.; Opal, Steven M. (2016). Infectious Diseases. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 79. ISBN 9780702063381. Archived from the original on 2017-09-11.

- ↑ Bennett, John E.; Dolin, Raphael; Blaser, Martin J. (2014). Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1760. ISBN 9781455748013. Archived from the original on 2017-09-11.

- ↑ Weiss, LM; O'Malley, D (2013). "Benign lymphadenopathies". Modern Pathology. 26 (Supplement 1): S88–S96. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2012.176. PMID 23281438.

- 1 2 Johannsen, EC; Kaye, KM (2009). "Epstein-Barr virus (infectious mononucleosis, Epstein-Barr virus-associated malignant disease, and other diseases)". In Mandell, GL; Bennett, JE; Dolin, R (eds.). Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious disease (7th ed.). Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0443068393.

- ↑ Robertson, Erle S. (2005). Epstein-Barr Virus. Horizon Scientific Press. p. 36. ISBN 9781904455035. Archived from the original on 2017-09-11.

- 1 2 Luzuriaga, K; Sullivan, JL (May 27, 2010). "Infectious mononucleosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 362 (21): 1993–2000. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1001116. PMID 20505178.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Ebell MH (November 2004). "Epstein-Barr virus infectious mononucleosis". American Family Physician. 70 (7): 1279–87. PMID 15508538.

- ↑ Shorvon, Simon D.; Andermann, Frederick; Guerrini, Renzo (2011). The Causes of Epilepsy: Common and Uncommon Causes in Adults and Children. Cambridge University Press. p. 470. ISBN 9781139495783. Archived from the original on 2018-01-04.

- ↑ Evans, Alfred S. (1 January 1948). "Liver involvement in infectious mononucleosis". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 27 (1): 106–110. doi:10.1172/JCI101913. PMC 439479. PMID 16695521.

- 1 2 Rezk SA, Zhao X, Weiss LM (September 2018). "Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated lymphoid proliferations, a 2018 update". Human Pathology. 79: 18–41. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2018.05.020. PMID 29885408.

- 1 2 Odumade OA, Hogquist KA, Balfour HH (January 2011). "Progress and problems in understanding and managing primary Epstein-Barr virus infections". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 24 (1): 193–209. doi:10.1128/CMR.00044-10. PMC 3021204. PMID 21233512.

- ↑ Richardson, M; Elliman, D; Maguire, H; Simpson, J; Nicoll, A (April 2001). "Evidence base of incubation periods, periods of infectiousness and exclusion policies for the control of communicable diseases in schools and preschools". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 20 (4): 380–91. doi:10.1097/00006454-200104000-00004. PMID 11332662.

- ↑ Mononucleosis and Epstein-Barr: What's the connection? Archived 2013-06-06 at the Wayback Machine. MayoClinic.com (2011-11-22). Retrieved on 2013-08-03.

- ↑ Schonbeck, John and Frey, Rebecca. The Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Vol. 2. 4th ed. Detroit: Gale, 2011. Online.

- 1 2 Larsen, Laura. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Sourcebook. Health Reference Series Detroit: Omnigraphics, Inc., 2009. Online.

- ↑ Carson-DeWitt and Teresa G. The Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Vol. 2. 3rd ed. Detroit: Gale, 2006.

- ↑ Cozad J (March 1996). "Infectious mononucleosis". The Nurse Practitioner. 21 (3): 14–6, 23, 27–8. doi:10.1097/00006205-199603000-00002. PMID 8710247.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ Elana Pearl Ben-Joseph. "How Long Is Mono Contagious?". Kidshealth.org. Archived from the original on 2016-11-19. Retrieved 2016-11-19. Date reviewed: January 2013

- ↑ ped/705 at eMedicine

- ↑ "The Lymphatic System". Lymphangiomatosis & Gorham's disease Alliance. Archived from the original on 2010-01-28. Retrieved 2010-02-08.

- 1 2 Ghosh, Amit K.; Habermann, Thomas (2007). Mayo Clinic Internal Medicine Concise Textbook. Informa Healthcare. ISBN 978-1-4200-6749-1.

- ↑ Rosenfield RE; Schmidt PJ; Calvo RC; McGinniss MH (1965). "Anti-i, a frequent cold agglutinin in infectious mononucleosis". Vox Sanguinis. 10 (5): 631–634. doi:10.1111/j.1423-0410.1965.tb01418.x. PMID 5864820.

- ↑ Hoagland RJ (June 1975). "Infectious mononucleosis". Primary Care. 2 (2): 295–307. PMID 1046252.

- ↑ "Mononucleosis". Mayo Clinic. 2017-08-03. Archived from the original on 2016-11-19. Retrieved 2017-08-06.

- ↑ Elgh, F; Linderholm, M (1996). "Evaluation of six commercially available kits using purified heterophile antigen for the rapid diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis compared with Epstein-Barr virus-specific serology". Clinical and Diagnostic Virology. 7 (1): 17–21. doi:10.1016/S0928-0197(96)00245-0. PMID 9077426.

- ↑ Cai, X; Ebell, MH; Haines, L (November 2021). "Accuracy of Signs, Symptoms, and Hematologic Parameters for the Diagnosis of Infectious Mononucleosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine : JABFM. 34 (6): 1141–1156. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2021.06.210217. PMID 34772769.

- 1 2 3 Longmore, Murray; Ian Wilkinson; Tom Turmezei; Chee Kay Cheung (2007). Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine, 7th edition. Oxford University Press. p. 389. ISBN 978-0-19-856837-7.

- ↑ Bravender, T (August 2010). "Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and infectious mononucleosis". Adolescent Medicine: State of the Art Reviews. 21 (2): 251–64, ix. PMID 21047028.

- ↑ Mark H. Beers ... (2006). Beers MH, Porter RS, Jones TV, Kaplan JL, Berkwits M (eds.). The Merck manual of diagnosis and therapy (18th ed.). Whitehouse Station (NJ): Merck Research Laboratories. ISBN 978-0-911910-18-6.

- ↑ Putukian, M; O'Connor, FG; Stricker, P; McGrew, C; Hosey, RG; Gordon, SM; Kinderknecht, J; Kriss, V; Landry, G (July 2008). "Mononucleosis and athletic participation: an evidence-based subject review" (PDF). Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 18 (4): 309–15. doi:10.1097/JSM.0b013e31817e34f8. PMID 18614881. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ↑ National Center for Emergency Medicine Informatics - Mononucleosis "Mononucleosis (Glandular Fever)". Archived from the original on 2009-05-15. Retrieved 2009-09-11.

- ↑ Rezk, Emtithal; Nofal, Yazan H.; Hamzeh, Ammar; Aboujaib, Muhammed F.; AlKheder, Mohammad A.; Al Hammad, Muhammad F. (2015-11-08). "Steroids for symptom control in infectious mononucleosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11): CD004402. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004402.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7047551. PMID 26558642.

- ↑ "Infectious Mononucleosis". WebMD. January 24, 2006. Archived from the original on July 6, 2006. Retrieved 2006-07-10.

- ↑ Antibiotic Expert Group. Therapeutic guidelines: Antibiotic. 13th ed. North Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines; 2006.

- ↑ Torre D, Tambini R; Tambini (1999). "Acyclovir for treatment of infectious mononucleosis: a meta-analysis". Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 31 (6): 543–47. doi:10.1080/00365549950164409. PMID 10680982.

- ↑ De Paor, M; O'Brien, K; Fahey, T; Smith, SM (8 December 2016). "Antiviral agents for infectious mononucleosis (glandular fever)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12: CD011487. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011487.pub2. PMC 6463965. PMID 27933614.

- ↑ Rafailidis PI, Mavros MN, Kapaskelis A, Falagas ME (2010). "Antiviral treatment for severe EBV infections in apparently immunocompetent patients". J. Clin. Virol. 49 (3): 151–57. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2010.07.008. PMID 20739216.

- ↑ "Glandular fever - NHS". National Health Service (NHS). 2010-09-09. Archived from the original on 2010-09-08. Retrieved 2010-09-09.

- ↑ Tyring, Stephen; Moore, Angela Yen; Lupi, Omar (2016). Mucocutaneous Manifestations of Viral Diseases: An Illustrated Guide to Diagnosis and Management (2 ed.). CRC Press. p. 125. ISBN 9781420073133. Archived from the original on 2017-09-11.

- 1 2 American Medical Society for Sports Medicine (24 April 2014), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Medical Society for Sports Medicine, archived from the original on 29 July 2014, retrieved 29 July 2014, which cites

- Putukian, M; O'Connor, FG; Stricker, P; McGrew, C; Hosey, RG; Gordon, SM; Kinderknecht, J; Kriss, V; Landry, G (Jul 2008). "Mononucleosis and athletic participation: an evidence-based subject review". Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 18 (4): 309–15. doi:10.1097/JSM.0b013e31817e34f8. PMID 18614881.

- Spielmann, AL; DeLong, DM; Kliewer, MA (Jan 2005). "Sonographic evaluation of spleen size in tall healthy athletes". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 184 (1): 45–9. doi:10.2214/ajr.184.1.01840045. PMID 15615949.

- ↑ Jensen, Hal B (June 2000). "Acute complications of Epstein-Barr virus infectious mononucleosis". Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 12 (3): 263–268. doi:10.1097/00008480-200006000-00016. ISSN 1040-8703. PMID 10836164.

- ↑ Aghenta A; Osowo, A; Thomas, J (May 2008). "Symptomatic atrial fibrillation with infectious mononucleosis". Canadian Family Physician. 54 (5): 695–696. PMC 2377232. PMID 18474702.

- ↑ Handel AE, Williamson AJ, Disanto G, Handunnetthi L, Giovannoni G, Ramagopalan SV (September 2010). "An updated meta-analysis of risk of multiple sclerosis following infectious mononucleosis". PLOS One. 5 (9): e12496. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...512496H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012496. PMC 2931696. PMID 20824132.

- ↑ Pattle, SB; Farrell, PJ (November 2006). "The role of Epstein-Barr virus in cancer". Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 6 (11): 1193–205. doi:10.1517/14712598.6.11.1193. PMID 17049016.

- ↑ Sitki-Green D, Covington M, Raab-Traub N (February 2003). "Compartmentalization and Transmission of Multiple Epstein-Barr Virus Strains in Asymptomatic Carriers". Journal of Virology. 77 (3): 1840–1847. doi:10.1128/JVI.77.3.1840-1847.2003. PMC 140987. PMID 12525618.

- ↑ Hadinoto V, Shapiro M, Greenough TC, Sullivan JL, Luzuriaga K, Thorley-Lawson DA (February 1, 2008). "On the dynamics of acute EBV infection and the pathogenesis of infectious mononucleosis". Blood. 111 (3): 1420–1427. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-06-093278. PMC 2214734. PMID 17991806.

- ↑ Altschuler, EL (1 September 1999). "Antiquity of Epstein-Barr virus, Sjögren's syndrome, and Hodgkin's disease--historical concordance and discordance". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 91 (17): 1512–3. doi:10.1093/jnci/91.17.1512A. PMID 10469761. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- 1 2 Evans, AS (March 1974). "The history of infectious mononucleosis". The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 267 (3): 189–95. doi:10.1097/00000441-197403000-00006. PMID 4363554.

- ↑ Н. Филатов: Лекции об острых инфекционных болезнях у детей [N. Filatov: Lektsii ob ostrikh infeksionnîkh boleznyakh u dietei]. 2 volumes. Moscow, A. Lang, 1887.

- ↑ E. Pfeiffer: Drüsenfieber. Jahrbuch für Kinderheilkunde und physische Erziehung, Wien, 1889, 29: 257–264.

- 1 2 Elsevier, Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary, Elsevier, archived from the original on 2014-01-11, retrieved 2020-07-24. Headword "mononucleosis".

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ↑ Sprunt TPV, Evans FA. Mononuclear leukocytosis in reaction to acute infection (infectious mononucleosis). Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital. Baltimore, 1920;31:410-417.

- ↑ "Historical Timeline | Yale School of Public Health". publichealth.yale.edu. Archived from the original on 2019-06-19. Retrieved 2019-01-04.

- ↑ Miller, George (December 21, 2006). "Book Review: Epstein–Barr Virus". New England Journal of Medicine. 355 (25): 2708–2709. doi:10.1056/NEJMbkrev39523.

- ↑ Henle G, Henle W, Diehl V (January 1968). "Relation of Burkitt's tumor-associated herpes-ytpe virus to infectious mononucleosis". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 59 (1): 94–101. Bibcode:1968PNAS...59...94H. doi:10.1073/pnas.59.1.94. PMC 286007. PMID 5242134.

- ↑ Fountain, Henry (1996-01-25). "Alfred S. Evans, 78, Expert On Origins of Mononucleosis". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2019-01-05. Retrieved 2019-01-04.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Infectious mononucleosis at Curlie