Hib vaccine

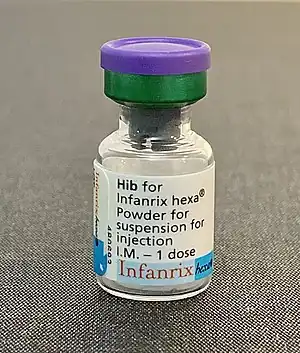

Hib white powder for Infanrix hexa injection | |

| Vaccine description | |

|---|---|

| Target disease | Haemophilus influenzae type b |

| Type | Conjugate vaccine |

| Names | |

| Trade names | ActHIB, Hiberix, OmniHIB, others |

| Clinical data | |

| Main uses | Prevent Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) infection[1] |

| Side effects | Pain at site of injection, fever[2] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of use | IM |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a607015 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status |

|

The Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccine, commonly known as Hib vaccine, is a vaccine used to provide protection against Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), a bacteria that can cause Haemophilus influenzae disease.[1] In countries that include it as a routine vaccine, rates of severe Hib infections have decreased more than 90%.[1] It has therefore resulted in a decrease in the rate of meningitis, pneumonia, and epiglottitis.[2] It is given by injection into a muscle.[2]

It is recommended for all children by both the World Health Organization (WHO) and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).[1][4] Two or three doses should be given before six months of age.[5] In the United States a fourth dose is recommended between 12 and 15 months of age.[6] The first dose is recommended around six weeks of age with at least four weeks between doses.[2] If only two doses are used, another dose later in life is recommended.[2] A booster dose is not required.[7]

Severe side effects are uncommon.[2] About 20 to 25% of people develop pain at the site of injection while about 2% develop a fever.[2] There is no clear association with severe allergic reactions.[2] The Hib vaccine is available by itself, or in various combination with diphtheria/tetanus/pertussis vaccine, polio vaccine, hepatitis B vaccine and meningitis C vaccine.[5] All Hib vaccines that are currently used are conjugate vaccine.[1]

The first Hib vaccine was developed in Finland in the early 1970s and was replaced by conjugate vaccines in the late 1980s.[8] As of 2013, 184 countries include it in their routine vaccinations.[2] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[9] The vaccine in combined form, is inexpensive, costing less than US$2 per dose[1]

Medical uses

%252C_OWID.svg.png.webp)

Hib conjugate vaccines have been shown to be universally effective against all manifestations of Hib disease, with a clinical efficacy among fully vaccinated children estimated to be between 95–100%. The vaccine has also been shown to be immunogenic in patients at high risk of invasive disease. Hib vaccine is not effective against non-type B Haemophilus influenzae. However, non-type B disease is rare in comparison to pre-vaccine rates of Haemophilus influenzae type B disease.[10]

Impact

Prior to introduction of the conjugate vaccine, Hib was a leading cause of childhood meningitis, pneumonia, and epiglottitis in the United States, causing an estimated 20,000 cases a year in the early 1980s, mostly in children under five years old. Since routine vaccination began, the incidence of Hib disease has declined by greater than 99%, effectively eliminating Hib as a public health problem. Similar reductions in disease occurred after introduction of the vaccine in Western Europe and developing countries.

After routine use of the vaccine in the United States from 1980 to 1990, the rate of invasive Hib disease decreased from 40–100 per 100,000 children down to fewer than one per 100,000.[11]

Recommendations

The CDC and the WHO recommend that all infants be vaccinated using a polysaccharide-protein conjugate Hib vaccine, starting after the age of six weeks. The vaccination is also indicated in people without a spleen.[12]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is not established.[13]

Side effects

Clinical trials and ongoing surveillance have shown Hib vaccine to be safe. In general, adverse reactions to the vaccine are mild. The most common reactions are mild fever, loss of appetite, transient redness, swelling, or pain at the site of injection, occurring in 5–30% of vaccine recipients. More severe reactions are extremely rare.[10]

Mechanisms of action

Polysaccharide vaccine

Haemophilus influenzae type b is a bacterium with a polysaccharide capsule; the main component of this capsule is polyribosyl ribitol phosphate (PRP). Anti-PRP antibodies have a protective effect against Hib infections. Thus, purified PRP was considered a good candidate for a vaccine. However, the antibody response to PRP diminished rapidly after administration. This problem was due to recognition of the PRP antigen by B cells, but not T cells. In other words, even though B cell recognition was taking place, T cell recruitment (via MHC class II) was not, which compromised the immune response. This interaction with only B cells is termed T-independent (TI). This process also inhibits the formation of memory B cells, thus compromising long term immune system memory.[14][15]

Conjugate vaccine

PRP covalently linked to a protein carrier was found to elicit a greater immune response than the polysaccharide form of the vaccine. This is due to the protein carrier being highly immunogenic in nature. The conjugate formulations show responses which are consistent with T-cell recruitment (namely a much stronger immune response). A memory effect (priming of the immune system against future attack by Hib) is also observed after administration; indicative that memory B cell formation is also improved over that of the polysaccharide form. Since optimal contact between B cells and T cells is required (via MHC II) to maximize antibody production, it is reasoned that the conjugate vaccine allows B cells to properly recruit T cells, this is in contrast to the polysaccharide form in which it is speculated that B cells do not interact optimally with T cells leading to the TI interaction.[14][15]

History

Polysaccharide vaccine

The first Hib vaccine licensed was a pure polysaccharide vaccine, first marketed in the United States in 1985.[16] Similar to other polysaccharide vaccines, immune response to the vaccine was highly age-dependent. Children under 18 months of age did not produce a positive response for this vaccine. As a result, the age group with the highest incidence of Hib disease was unprotected, limiting the usefulness of the vaccine. The vaccine was withdrawn from the market in 1988.

Conjugate vaccine

The shortcomings of the polysaccharide vaccine led to the production of the Hib polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccine.[16] Attaching Hib polysaccharide to a protein carrier greatly increased the ability of the immune system of young children to recognize the polysaccharide and develop immunity. There are currently three types of conjugate vaccine, utilizing different carrier proteins for the conjugation process: inactivated tetanospasmin (also called tetanus toxoid), mutant diphtheria protein, and meningococcal group B outer membrane protein.

Combination vaccines

Multiple combinations of Hib and other vaccines have been licensed in the United States, reducing the number of injections necessary to vaccinate a child. Hib vaccine combined with diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis–polio vaccines and Hepatitis B vaccines are available in the United States. The World Health Organization (WHO) has certified several Hib vaccine combinations, including a pentavalent diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus-hepatitis B-Hib, for use in developing countries. There is not yet sufficient evidence on how effective this combined pentavalent vaccine is in relation to the individual vaccines.[17]

Menitorix: Hib with meningitis C (MenC-Hib)

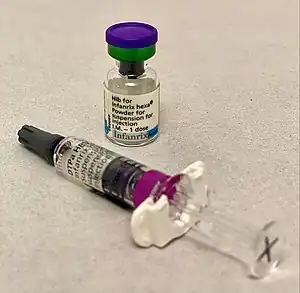

Menitorix: Hib with meningitis C (MenC-Hib) Infanrix hexa: Hib with hepatitis B, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis and poliomyelitis (DTP-IPV-HBV-Hib)

Infanrix hexa: Hib with hepatitis B, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis and poliomyelitis (DTP-IPV-HBV-Hib) Act-HIb

Act-HIb

Developing world

Introduction of Hib vaccine in developing countries lagged behind that in developed countries for several reasons. The expense of the vaccine was large in comparison to the standard EPI vaccines. Poor disease surveillance systems and inadequate hospital laboratories failed to detect the disease, leading many experts to believe that Hib did not exist in their countries. And health systems in many countries were struggling with the current vaccines they were trying to deliver.

GAVI and the Hib Initiative

In order to remedy these issues, the GAVI Alliance took active interest in the vaccine. GAVI offers substantial subsidization of Hib vaccine for countries interested in using the vaccine, as well as financial support for vaccine systems and safe injections. In addition, GAVI created the Hib Initiative to catalyze uptake of the vaccine. The Hib Initiative uses a combination of collecting and disseminating existing data, research, and advocacy to assist countries in the making a decision about using the Hib vaccine. Currently, 61 out of 72 low-income countries are planning on introducing the vaccine by the end of 2009.[18]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mutsaerts, Eleanor A. M. L.; Madhi, Shabir A. (2022). "11.3. Immunisation and vaccination". In Detels, Roger; Karim, Quarraisha Abdool; Baum, Fran (eds.). Oxford Textbook of Global Public Health (7th ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 584–589. ISBN 978-0-19-881680-5. Archived from the original on 20 October 2023. Retrieved 9 October 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 World Health Organization (September 2013). "Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) Vaccination Position Paper — July 2013". Weekly Epidemiological Record. 88 (39): 413–26. hdl:10665/242126. PMID 24143842.

- Lay summary in: (PDF) https://www.who.int/immunization/position_papers/Hib_summary.pdf.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help)

- Lay summary in: (PDF) https://www.who.int/immunization/position_papers/Hib_summary.pdf.

- 1 2 Professional Drug Facts

- ↑ "Haemophilus b conjugate vaccines for prevention of Haemophilus influenzae type b disease among infants and children two months of age and older. Recommendations of the immunization practices advisory committee (ACIP)". MMWR Recomm Rep. 40 (RR-1): 1–7. January 1991. PMID 1899280. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- 1 2 Heininger, Ulrich (2021). "19. Haemophilus influenza Type b (Hib) vaccines". In Vesikari, Timo; Damme, Pierre Van (eds.). Pediatric Vaccines and Vaccinations: A European Textbook (Second ed.). Switzerland: Springer. pp. 195–206. ISBN 978-3-030-77172-0. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ "Hib (Haemophilus Influenzae Type B)". Archived from the original on 8 April 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ↑ Lampiris, Harry W.; maddix, Daniel S. (2020). "Appendix: Vaccines, immune globulins, and other complex biologic products". In Katzung, Bertram G.; Trevor, Anthony J. (eds.). Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (15th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 1228. ISBN 978-1-260-45231-0. Archived from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ↑ Saleh, Amr; Qamar, Shahraz; Tekin, Aysun; Singh, Romil; Kashyap, Rahul (July 2021). "Vaccine Development Throughout History". Cureus. 13 (7): e16635. doi:10.7759/cureus.16635. ISSN 2168-8184. PMID 34462676. Archived from the original on 21 May 2022. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- 1 2 "Recommendation of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee (ACIP) Polysaccharide Vaccine for Prevention of Haemophilus influenzae Type b Disease". MMWR Weekly. 34 (15): 201–5. 19 April 1985. ISSN 0149-2195. Archived from the original on 15 October 2008. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

- ↑ "Haemophilus influenzae Disease (Including Hib)". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 25 September 2012. Archived from the original on 30 January 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ↑ "Asplenia and Adult Vaccination". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 14 February 2019. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ↑ "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 1 July 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- 1 2 Kelly, Dominic F.; Moxon, E. Richard; Pollard, Andrew J. (1 October 2004). "Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccines". Immunology. 113 (2): 163–174. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01971.x. ISSN 1365-2567. PMC 1782565. PMID 15379976.

- 1 2 Finn, Adam (1 January 2004). "Bacterial polysaccharide–protein conjugate vaccines". British Medical Bulletin. 70 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldh021. ISSN 0007-1420. PMID 15339854. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- 1 2 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2006). Atkinson W, Hamborsky J, McIntyre L, Wolfe S (eds.). Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (9th ed.). Washington, D.C.: Public Health Foundation.

- ↑ Bar-On, ES; Goldberg, E; Hellmann, S; Leibovici, L (18 April 2012). "Combined DTP-HBV-HIB vaccine versus separately administered DTP-HBV and HIB vaccines for primary prevention of diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, hepatitis B and Haemophilus influenzae B (HIB)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4 (4): CD005530. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005530.pub3. PMID 22513932.

- ↑ "Hib Initiative". Archived from the original on 5 September 2008. Retrieved 3 October 2008.

61 of 72 GAVI countries have introduced or will introduce Hib vaccine into their routine immunization program [sic] by 2009

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|

- "Haemophilus B Conjugate Vaccine (Meningococcal Protein Conjugate)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 22 July 2017. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- "Haemophilus b Conjugate Vaccine (Tetanus Toxoid Conjugate)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 24 April 2019. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- "Hiberix". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 30 April 2018. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2019.