Rifapentine

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Priftin |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Macrolactam |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| Defined daily dose | 0.1 gram[2] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a616011 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | increases when administered with food |

| Chemical and physical data | |

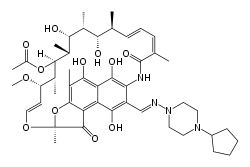

| Formula | C47H64N4O12 |

| Molar mass | 877.031 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 179 to 180 °C (354 to 356 °F) |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Rifapentine, sold under the brand name Priftin, is an antibiotic used in the treatment of tuberculosis.[3] In active tuberculosis it is used together with other antituberculosis medications.[3] In latent tuberculosis it is typically used with isoniazid.[4] It is taken by mouth.[3]

Common side effects include low neutrophil counts in the blood, elevated liver enzymes, and white blood cells in the urine.[3] Serious side effects may include liver problems or Clostridium difficile associated diarrhea.[3] It is unclear if use during pregnancy is safe.[3] Rifapentine is in the rifamycin family of medication and works by blocking DNA-dependent RNA polymerase.[3]

Rifapentine was approved for medical use in the United States in 1998.[3] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[5] In the United States it costs $100–200 per month.[6] In many areas of the world it is not easy to get as of 2015.[7]

Medical uses

A systematic review of regimens for prevention of active tuberculosis in HIV-negative individuals with latent TB found that a weekly, directly observed regimen of rifapentine with isoniazid for three months was as effective as a daily, self-administered regimen of isoniazid for nine months. The 3-month rifapentine-isoniazid regimen had higher rates of treatment completion and lower rates of hepatotoxicity. However, the rate of treatment-limiting adverse events was higher in the rifapentine-isoniazid regimen compared to the 9-month isoniazid regimen.[8]

Pregnancy

Rifapentine has been assigned a pregnancy category C by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Rifapentine in pregnant women has not been studied, but animal reproduction studies have resulted in fetal harm and were teratogenic. If rifapentine or rifampin are used in late pregnancy, coagulation should be monitored due to a possible increased risk of maternal postpartum hemorrhage and infant bleeding.[9]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 0.1 gram (by mouth).[2]

Side effects

Common side effects are hyperuricemia, pyuria, hematuria, urinary tract infection, proteinuria, neutropenia, anemia, and hypoglycemia.[9]

Contraindications

Rifapentine should be avoided in patients with an allergy to the rifamycin class of drugs.[9] This drug class includes rifampicin and rifabutin. [10]

Interactions

Rifapentine induces metabolism by CYP3A4, CYP2C8 and CYP2C9 enzymes. It may be necessary to adjust the dosage of drugs metabolized by these enzymes if they are taken with rifapentine. Examples of drugs that may be affected by rifapentine include warfarin, propranolol, digoxin, protease inhibitors and birth control pills.[9]

Chemistry

The chemical structure of rifapentine is similar to that of rifamycin, with the notable substitution of a methyl group for a cyclopentane (C5H9) group.

History

Rifapentine was first synthesized in 1965, by the same company that produced rifampicin. The drug was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in June 1998.[11][12] It is made from rifampicin.

Rifapentine was granted orphan drug designation by the FDA in June 1995,[13] and by the European Commission in June 2010.[14]

See also

References

- ↑ "Rifapentine (Priftin) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 2 December 2019. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- 1 2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Rifapentine". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2015). The selection and use of essential medicines. Twentieth report of the WHO Expert Committee 2015 (including 19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines and 5th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for Children). Geneva: World Health Organization. pp. 35–8. hdl:10665/189763. ISBN 9789241209946. ISSN 0512-3054. WHO technical report series;994.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 53. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ↑ Nieburg, Phillip; Dubovi, Talia; Angelo, Sahil (2015). Tuberculosis—A Complex Health Threat: A Policy Primer of Global TB Challenges. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 15. ISBN 9781442240957. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20.

- ↑ Sharma SK, Sharma A, Kadhiravan T, et al. (July 2013). "Rifamycins (rifampicin, rifabutin and rifapentine) compared to isoniazid for preventing tuberculosis in HIV-negative people at risk of active TB". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7: CD007545. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007545.pub2. PMC 6532682. PMID 23828580.

- 1 2 3 4 "Priftin- rifapentine tablet, film coated". DailyMed. 22 October 2019. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ↑ CDC. (2013) Core Curriculum on Tuberculosis: What the Clinician Should Know. Retrieved from "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-07-11. Retrieved 2017-09-10.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). - ↑ "Drug Approval Package: Priftin/Rifapentine NDA# 21024". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 30 March 2001. Archived from the original on 30 March 2021. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ↑ "Priftin". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ↑ "Rifapentine Orphan Drug Designation and Approval". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 24 December 1999. Archived from the original on 21 July 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ↑ "EU/3/10/750". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 21 June 2010. EMA/COMP/165383/2010. Archived from the original on 16 March 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

External links

- "Rifapentine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2020-02-10. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

| Identifiers: |

|---|