Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada disease

| Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada syndrome, uveomeningitis syndrome, uveomeningoencephalitic syndrome[1] | |

| |

| Dermatologic manifestation of VKH | |

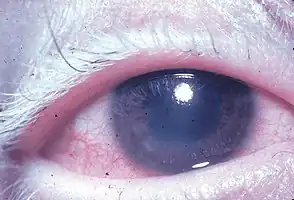

Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada disease (VKH) is a multisystem disease of presumed autoimmune cause that affects pigmented tissues, which have melanin. The most significant manifestation is bilateral, diffuse uveitis, which affects the eyes.[2][3] VKH may variably also involve the inner ear, with effects on hearing, the skin and the meninges of the central nervous system.[2][3][4][5][6]

Signs and symptoms

Overview

The disease is characterised by bilateral diffuse uveitis, with pain, redness and blurring of vision. The eye symptoms may be accompanied by a varying constellation of systemic symptoms, such as auditory (tinnitus,[6] vertigo,[6] and hypoacusis), neurological (meningismus, with malaise, fever, headache, nausea, abdominal pain, stiffness of the neck and back, or a combination of these factors;[6] meningitis,[4] CSF pleocytosis, cranial nerve palsies, hemiparesis, transverse myelitis and ciliary ganglionitis[6]), and cutaneous manifestations, including poliosis, vitiligo, and alopecia.[4][5][6] The vitiligo often is found at the sacral region.[6]

Phases

The sequence of clinical events in VKH is divided into four phases: prodromal, acute uveitic, convalescent, and chronic recurrent.[2][5][6]

The prodromal phase may have no symptoms, or may mimic a non-specific viral infection, marked by flu-like symptoms that typically last for a few days.[6] There may be fever, headache, nausea, meningismus, dysacusia (discomfort caused by loud noises or a distortion in the quality of the sounds being heard), tinnitus, and/or vertigo.[6][7] Eye symptoms can include orbital pain, photophobia and tearing.[6] The skin and hair may be sensitive to touch.[6][7] Cranial nerve palsies and optic neuritis are uncommon.[6]

The acute uveitic phase occurs a few days later and typically lasts for several weeks.[6] This phase is heralded by bilateral panuveitis causing blurring of vision.[6] In 70% of VKH, the onset of visual blurring is bilaterally contemporaneous; if initially unilateral, the other eye is involved within several days.[6] The process can include bilateral granulomatous anterior uveitis, variable degree of vitritis, thickening of the posterior choroid with elevation of the peripapillary retinal choroidal layer, optic nerve hyperemia and papillitis, and multiple exudative bullous serous retinal detachments.[2][5][6]

The convalescent phase is characterized by gradual tissue depigmentation of skin with vitiligo and poliosis, sometimes with nummular depigmented scars, as well as alopecia and diffuse fundus depigmentation resulting in a classic orange-red discoloration ("sunset glow fundus"[5][8][7]) and retinal pigment epithelium clumping and/or migration.[2][6]

The chronic recurrent phase may be marked by repeated bouts of uveitis, but is more commonly a chronic, low-grade, often subclinical, uveitis that may lead to granulomatous anterior inflammation, cataracts, glaucoma and ocular hypertension.[2][3][5][6] Full-blown recurrences are, however, rare after the acute stage is over.[8] Dysacusia may occur in this phase.[7]

Cause

Although there is sometimes a preceding viral infection, or skin or eye trauma,[6] the exact underlying initiator of VKH disease remains unknown.[4] However, VKH is attributed to aberrant T-cell-mediated immune response directed against self-antigens found on melanocytes.[3][4][6] Stimulated by interleukin 23 (IL-23), T helper 17 cells and cytokines such as interleukin 17 (IL-17) appear to target proteins in the melanocyte.[8][9]

Risk factors

Affected individuals are typically 20 to 50 years old.[3][4] The female to male ratio is 2:1.[4][5][6] By definition, there is no history of either surgical or accidental ocular trauma.[3] VKH is more common in Asians, Latinos, Middle Easterners, American Indians, and Mexican Mestizos; it is much less common in Caucasians and in blacks from sub-Saharan Africa.[3][4][5][6]

VKH is associated with a variety of genetic polymorphisms that relate to immune function. For example, VKH has been associated with human leukocyte antigens (HLA) HLA-DR4 and DRB1/DQA1,[10] copy-number variations (CNV) of complement component 4,[10] a variant IL-23R locus[10] and with various other non-HLA genes.[10] HLA-DRB1*0405 in particular appears to play an important susceptibility role.[2][4][8][6]

Diagnosis

If tested in the prodromal phase, CSF pleocytosis is found in more than 80%,[6][7] mainly lymphocytes.[7] This pleocytosis resolves in about 8 weeks even if chronic uveitis persists.[7]

Functional tests may include electroretinogram and visual field testing.[2] Diagnostic confirmation and an estimation of disease severity may involve imaging tests such as retinography, fluorescein or indocyanine green angiography, optical coherence tomography and ultrasound.[2][5][9][7] For example, indocyanine green angiography may detect continuing choroidal inflammation in the eyes without clinical symptoms or signs.[5][8] Ocular MRI may be helpful[6] and auditory symptoms should undergo audiologic testing.[6] Histopathology findings from eye and skin are discussed by Walton.[6]

The diagnosis of VKH is based on the clinical presentation; the diagnostic differential is extensive, and includes (among others) sympathetic ophthalmia, sarcoidosis, primary intraocular B-cell lymphoma, posterior scleritis, uveal effusion syndrome, tuberculosis, syphilis, and multifocal choroidopathy syndromes.[3][6]

Types

Based on the presence of extraocular findings, such as neurological, auditory and integumentary manifestations, the "revised diagnostic criteria" of 2001[2][11] classify the disease as complete (eyes along with both neurological and skin), incomplete (eyes along with either neurological or skin) or probable (eyes without either neurological or skin) .[1][3][5][6][11] By definition, for research homogeneity purposes, there are two exclusion criteria: previous ocular penetrating trauma or surgery, and other concomitant ocular disease similar to VKH disease.[2][6][11]

Management

The acute uveitis phase of VKH is usually responsive to high-dose oral corticosteroids; parenteral administration is usually not required.[2][3][6] However, ocular complications may require a subtenon[6] or intravitreous injection of corticosteroids[4][6] or bevacizumab.[9] In refractory situations, other immunosuppressives such as cyclosporine,[2][3] or tacrolimus,[9] antimetabolites (azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil or methotrexate[9]), or biological agents such as intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) or infliximab may be needed.[2][6]

Outcomes

Visual prognosis is generally good with prompt diagnosis and aggressive immunomodulatory treatment.[2][3][8] Inner ear symptoms usually respond to corticosteroid therapy within weeks to months; hearing usually recovers completely.[6] Chronic eye effects such as cataracts, glaucoma, and optic atrophy can occur.[6] Skin changes usually persist despite therapy.[6]

Eponym

VKH syndrome is named for ophthalmologists Alfred Vogt from Switzerland and Yoshizo Koyanagi and Einosuke Harada from Japan.[12][13][14][15] Several authors, including the Arabic doctor Mohammad-al-Ghâfiqî in the 12th century as well as Jacobi, Nettelship and Tay in the 19th century, had described poliosis, neuralgias and hearing disorders.[15] This constellation was probably often due to sympathetic ophthalmia but likely included examples of VKH.[15] Koyanagi's first description of the disease was in 1914, but was preceded by Jujiro Komoto, Professor of Ophthalmology at the University of Tokyo, in 1911.[15] It was the much later article, published in 1929, that definitively associated Koyanagi with the disease.[15] Harada's 1926 paper is recognized for its comprehensive description of what is now known as Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada disease.[15]

References

- 1 2 "Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease". National Organization for Rare Disorders. 2014. Archived from the original on 2018-08-26. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Sakata VM, da Silva FT, Hirata CE, de Carvalho JF, Yamamoto JH (2014). "Diagnosis and classification of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease". Autoimmun Rev. 13 (4–5): 550–5. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.023. PMID 24440284.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Damico FM, Kiss S, Young LH (2005). "Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease". Semin Ophthalmol. 20 (3): 183–90. doi:10.1080/08820530500232126. PMID 16282153. S2CID 46680743.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Greco A, Fusconi M, Gallo A et al. (2013). "Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome". Autoimmun Rev. 12 (11): 1033–8. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2013.01.004. PMID 23567866.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Cunningham ET, Rathinam SR, Tugal-Tutkun I, Muccioli C, Zierhut M (2014). "Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease". Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 22 (4): 249–52. doi:10.3109/09273948.2014.939530. PMID 25014114. S2CID 45185875.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 Walton RC (Feb 12, 2014). "Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease". Medscape. Archived from the original on August 12, 2020. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Rao, PK; Rao, NA (2006). "Chapter 10. Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada disease and Sympathetic Ophthalmia". In Pleyer, U; Foster, CS (eds.). Uveitis and Immunological Disorders. Essentials in Ophthalmology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 145–155. ISBN 9783540307983.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Damico FM, Bezerra FT, Silva GC, Gasparin F, Yamamoto JH (2009). "New insights into Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease". Arq Bras Oftalmol. 72 (3): 413–20. doi:10.1590/s0004-27492009000300028. PMID 19668980.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 Bordaberry MF (2010). "Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease: diagnosis and treatments update". Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 21 (6): 430–5. doi:10.1097/ICU.0b013e32833eb78c. PMID 20829689. S2CID 205670933.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - 1 2 3 4 Hou S, Kijlstra A, Yang P (2015). "Molecular Genetic Advances in Uveitis". Molecular Biology of Eye Disease. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. Vol. 134. pp. 283–298. doi:10.1016/bs.pmbts.2015.04.009. ISBN 9780128010594. PMID 26310161.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - 1 2 3 Read RW, Holland GN, Rao NA et al. (2001). "Revised diagnostic criteria for Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease: report of an international committee on nomenclature". Am. J. Ophthalmol. 131 (5): 647–52. doi:10.1016/s0002-9394(01)00925-4. PMID 11336942.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ↑ Vogt A. Frühzeitiges Ergrauen der Zilien und Bemerkungen über den sogenannten plötzlichen Eintritt dieser Veränderung. Klinische Monatsblätter für Augenheilkunde, Stuttgart, 1906, 44: 228-242.

- ↑ Koyanagi Y. Dysakusis, Alopecie und Poliosis bei schwerer Uveitis nicht traumatischen Ursprungs. Klinische Monatsblätter für Augenheilkunde, Stuttgart, 1929, 82: 194–211.

- ↑ Harada E. Clinical study of nonsuppurative choroiditis. A report of acute diffuse choroiditis. Acta Societatis ophthalmologicae Japonicae, 1926, 30: 356.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Herbort CP, Mochizuki M (2007). "Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease: inquiry into the genesis of a disease name in the historical context of Switzerland and Japan" (PDF). Int Ophthalmol. 27 (2–3): 67–79. doi:10.1007/s10792-007-9083-4. PMID 17468832. S2CID 32100373. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-12-20. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|

- American Academy of Ophthalmology: Identify and Treat Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Syndrome Archived 2021-03-31 at the Wayback Machine

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)