This article was co-authored by Language Academia. Language Academia is a private, online language school founded by Kordilia Foxstone. Kordilia and her team specialize in teaching foreign languages and accent reduction. Language Academia offers courses in several languages, including English, Spanish, and Mandarin.

There are 10 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 44,783 times.

English pronunciation can be tricky, especially for ESL (English as a Second Language) learners. Start by introducing how to pronounce English vowels and consonants. Some sounds rarely occur in other languages, so clearly explain how students should use their lips and tongues to form unfamiliar sounds. Since stress, rhythm, and intonation express nuanced meanings, offer plenty of examples of how these qualities function. Understanding native speakers’ speech habits is a key skill, so you should also help your students recognize how words blend together, contractions, and slang.

Steps

Introducing Basic Sounds

-

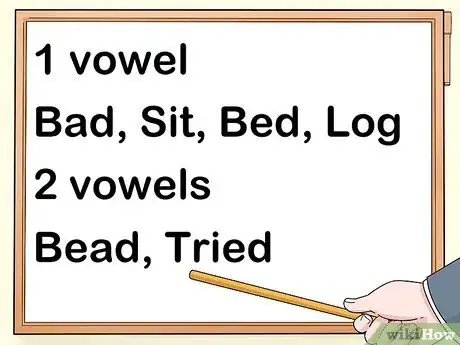

1Go over the basic rules of English phonics. Start with the English pronunciation of the Latin alphabet. Distinguish vowels and consonants, and note that every syllable in every word must contain a vowel (note that “y” sometimes count as a vowel). Discuss general rules for recognizing whether vowels are long or short, and note exceptions.[1]

- For instance, explain that a vowel in a 1-syllable word that ends in a consonant is usually short, as in “bad,” “bed,” “sit,” “log,” and “but.” Note exceptions, such as “told,” “scold,” or “child.”

- When 2 vowels are next to each other, the first vowel is usually long and the second is silent, as in “bead” or “tried.” Note exceptions to the rule, such as “chief” or the past tense usage of “read.”

-

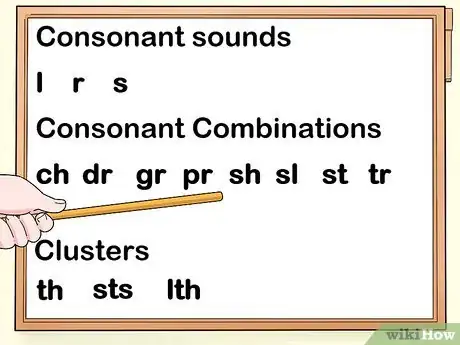

2Show students how to make sounds that combine consonants. After introducing simple consonant sounds, such as “l,” “r,” and “s,” add consonant combinations, including “ch,” “dr,” “gr,” “pr,” “sh,” “sl,” “st,” and “tr.” Clusters such as “th,” “str,” “sts,” and “lth,” might be challenging for some students. While many of these consonant combinations occur in other languages, some students might have difficulty with sounds that are unique to English.[2]

- For example, “th” occurs rarely in other languages and can be difficult for most ESL learners to master.

- Vietnamese native speakers typically have trouble with the consonant clusters “sts,” “ts,” and “str.”

- Mandarin and Korean native speakers often have trouble with combinations that include “r” or “l.”

Advertisement -

3Demonstrate sounds by exaggerating your mouth, lips, and tongue. Show students exactly how to use their mouth and tongue to make phonemes, or the basic sounds of the English language. Exaggerate your mouth’s round shape for the long “o” in “boat” and “low.” Tell students how and where to place their tongue to pronounce sounds like “th” and “l.”[3]

- Show students how you curl your tongue and touch it to the roof of your mouth to make the “l” in “lid.”

- Explain how you press your lips together to make a “b,” then quickly use your tongue to make the “l” in “blur.”

- Exaggerate how your tongue grazes and peeks past your upper front teeth to say the “th” in “that.”

-

4Encourage students to practice unfamiliar sounds diligently. Gently correct students if they use a more familiar sound when trying to make a sound that's challenging or doesn’t exist in their language. Tell them not to be discouraged if they have trouble, and explain that it takes time to train their mouth and tongue to move in unfamiliar ways.[4]

- The sound “th” is especially difficult, and students often substitute it with “t,” “f,” or “s.” Depending on a student’s native language, other tough sounds could include “l,” “r,” and soft “g” or “j.” Differentiating between “b” and “v” or “b” and “p” can also give students trouble.

- Remind students that using familiar sounds in place of more difficult ones can create important differences in meaning. Let them know that they could unintentionally say something inappropriate or be misunderstood if they use 1 sound in place of another.

-

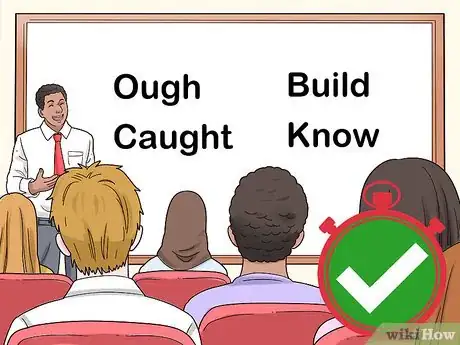

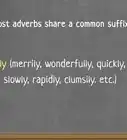

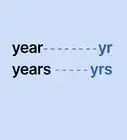

5Assign weekly vocabulary words to help students memorize exceptions. Covering the basic rules is a good starting point, but English is notorious for strange exceptions to every rule. Depending on age level, have students practice and memorize at least 10 to 20 words that don’t follow ordinary rules.[5]

- Examples include words with “ough,” such as “though,” “thought, “tough,” and “bough.” Other oddballs include “laugh,” “caught,” “friend,” “build,” “ocean,” and “know.”

-

6Use rubber bands to visualize voiced and unvoiced consonants. Hold a rubber band between your thumbs. Keep it short to help students understand how a syllable with an unvoiced consonant sounds short. Extend the rubber band to show how a syllable with a voiced consonant sounds longer.[6]

- For example, keep the rubber band short for “rice,” then extend it for “rise.” Both words end with an “s” sound, but the “s” is unvoiced in “rice” and voiced in “rise.” Note how the voiced “s” takes slightly longer to say and sounds more like a “z.”

- It’s relatively easy to hear the difference between the short “a” in “bat” and the long “a” in “base.” However, distinguishing voiced and unvoiced consonants can be trickier.

- Practicing syllable length with rubber bands is a good way to transition from teaching basic sounds to incorporating rhythm and stress.

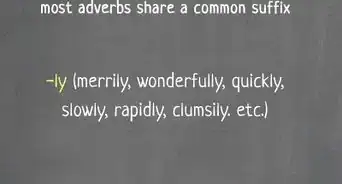

Practicing Rhythm and Stress

-

1Compare stress-timed and syllable-timed languages. If you’re teaching ESL, keep in mind that many of your students’ native languages are syllable-timed. Mention to students that they might be used to evenly stressing each word or every other syllable. Explain that, in English, particular words and syllables are stressed in order to convey meaning, focus, and emotion.[7]

- For example, in Romance languages, such as French, Spanish, and Italian, speech is rapid and words blend into each other with little or no stress. In Mandarin, tones and pitch can change an individual word's meaning, but stress and rhythm don't impact a statement's message or the emotions it conveys.

-

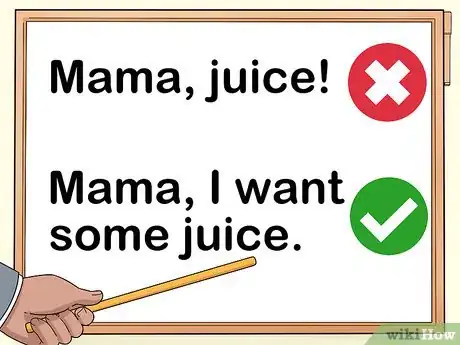

2Describe the differences between content and function words. Teach students that content words are essential to a phrase’s main idea. These words are usually stressed more than function words, which are used for grammatical purposes.[8]

- For instance, a toddler might use the content words “Mama, juice!” A complete, grammatically correct phrase would be, “Mama, I want some juice.” The focus word, or the most stressed word, is often the last content word of a sentence, as “juice” is in this example.

-

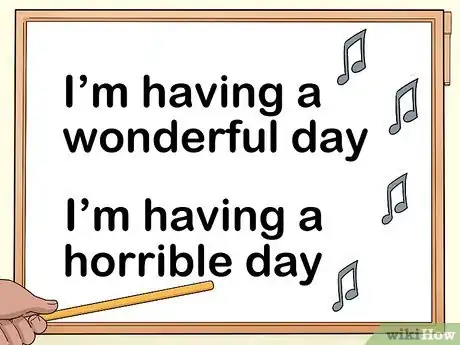

3Use kazoos to show students how to stress words and syllables. Provide examples of English sentences, and use a kazoo to hum their stresses and pitch changes. This will provide clear cues for students who have trouble recognizing emphasis and rhythm in speech alone. Students can also use their own kazoos to practice stress and rhythm.

- For example, hum the rhythm for “I’m having a wonderful day” and “I’m having a horrible day.”

- The kazoo will also come in handy when you teach students about rising and falling intonations in declarative sentences and questions.

-

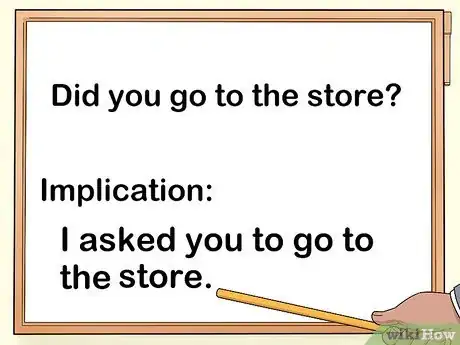

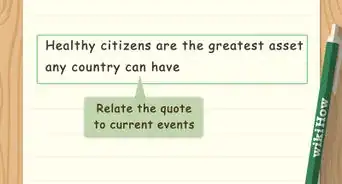

4Demonstrate how emphasis can change a phrase’s meaning. Recite a sentence with the same words, but change your emphasis with each repetition. Explain to students that changing the stressed word changes the statement’s implied meaning.

- For example, “Did you go to the store?” might imply, “I asked you to go to the store and want to know if you completed this task.”

- “Did you go to the store?” can mean, “Did you go to the store or to some other location?”

- ”Did you go to the store?” implies “Was it you or someone else who went to the store?”

Teaching Proper Intonation

-

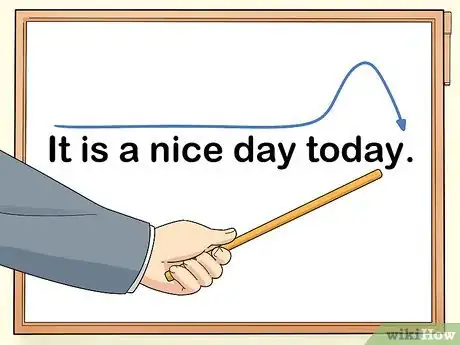

1Demonstrate falling intonation at the end of a declarative sentence. Explain that intonation usually falls at the end of a complete thought. The speaker lowers their pitch to indicate that they’ve finished making a declarative statement. Hum intonation for example sentences with a kazoo to make it easier for students to recognize changes in pitch.[9]

- A declarative sentence claims or asserts something. An imperative sentence gives a command, and intonation usually falls at the ends of these sentences, too.

- The other types of sentences are interrogative, which ask a question, and exclamatory, which declare something with excitement or emotion. Intonation usually rises at the ends of these sentences.

-

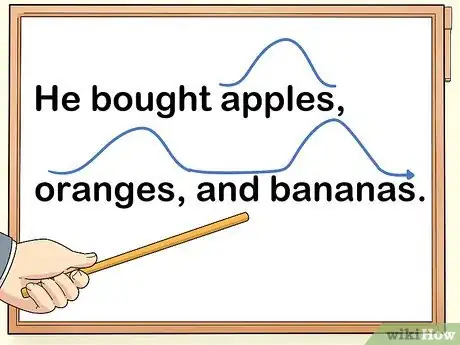

2Explain how intonation waves after a mid-sentence clause. Demonstrate how intonation waves, or falls and rises just slightly, to anticipate the statements that follow a clause or come next in a list. Provide examples such as independent clauses set off by commas, lists separated by serial commas, and phone numbers.

- For example, recite, “He bought apples, oranges, and bananas.” Exaggerate how you inflect “apples” and “oranges” to anticipate the next word in the list, but lower your pitch on “bananas” to indicate you’ve completed your thought.

- A more complex example would be, “When you go to the store, which is on your way home from work, please buy apples, oranges, and bananas.” Intonation subtly waves at “store” and “work” to anticipate the sentence’s next clauses, and rises and falls when the fruits are listed.

-

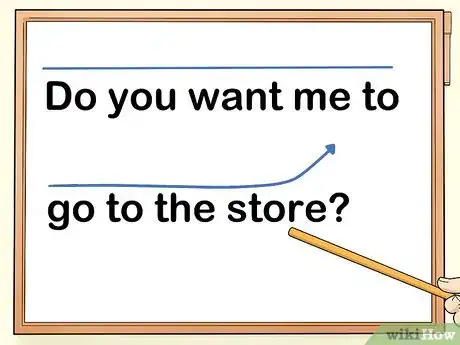

3Show students how intonation rises at the end of a question. Note that some statements are straightforward, such as “How was your day?” or “Will you hold this for me?” However, a speaker might end a seemingly declarative statement with a rising tone to ask for clarification or make an exclamation.[10]

- For example, “I should go to the store” looks like a declarative sentence. However, a speaker might raise their pitch at “store,” as if to say, “Do you want me to go to the store?”

- Additionally, rising intonation can indicate shock, surprise, or confusion. Exclamations such as "I am so proud of you!" or "Get out of the way!" typically begin at a higher pitch than a speaker's normal speech. Intonation often rises suddenly at the end of the exclamation.

-

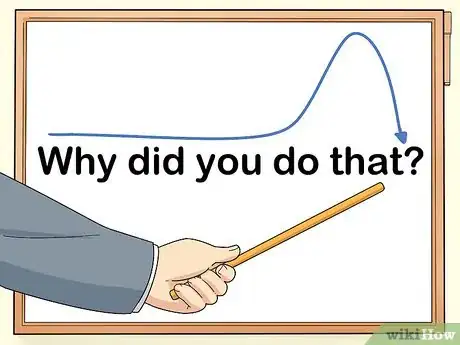

4Provide examples of subtle intonation cues that express meaning. Mention that speakers might end a question with a lower pitch to express dissatisfaction or sarcasm. Since these examples can be subtle, exaggerate your falling tone or use the kazoo to clearly mark the lower pitch.[11]

- An example could be, “Why did you do that,” as if to say, “I’m frustrated that you did that.”

- For ”What did they do now,” intonation might be lower and syllable length longer for “now,” which implies exasperation.

-

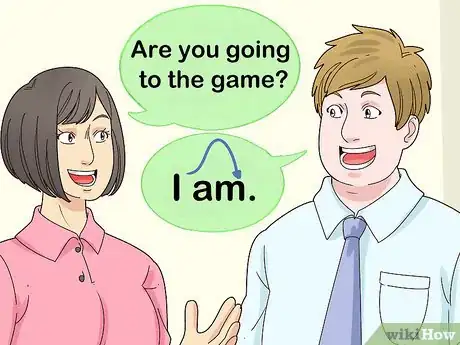

5Recite the same dialogue with enthusiastic and flat pitches. Demonstrate how important intonation is by performing 2 versions of a sample dialogue with a student. Have them ask you questions, and respond with varied, enthusiastic intonation. Perform the dialogue again, and respond to their questions with flat, uninterested, or sarcastic intonation.[12]

- Suppose the first question is, “Are you going to the game?” Explain how saying “I am” with a rising intonation expresses excitement, while replying with a falling intonation can indicate disappointment or disinterest.

- Use your facial expressions and body language to clarify how different pitches communicate emotions.

Explaining Linked and Reduced Sounds

-

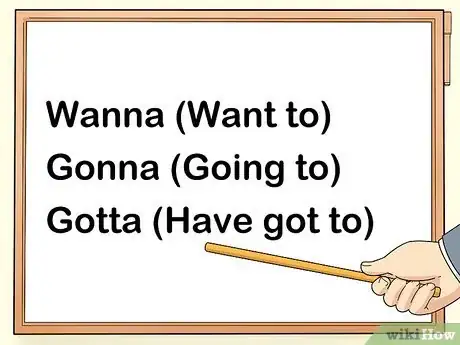

1Describe the schwa sound and its role in natural English pronunciation. Schwa sounds like a short “u,” as in “cup,” or the “a” in “about.” It’s the most common sound in the English language, and using it makes pronunciation sound more natural. Since native speakers commonly use it in place of precise pronunciation, it can also pose a challenge for ESL students.

- Examples of schwa include the second “o” in “doctor,” the “a” in “wizard,” and the “e” in “summer.”[13]

- Schwa is frequently used to reduce words and syllables. Note examples such as “wanna” instead of “want to,” “gonna” for “going to,” and “gotta” for “have a” or “have got to.”

-

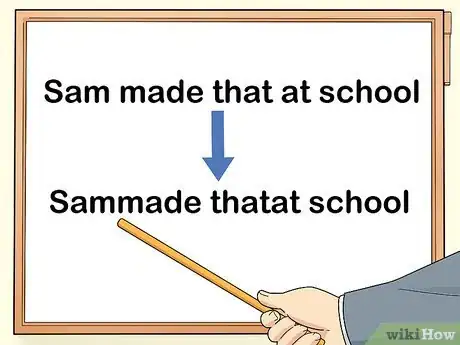

2Explain how words blend with magnetic blocks and phonetic writing. Write words on magnetic blocks or other objects that can be joined together. Stick the blocks together to show how vowels and consonants blend into each other when words are used in a sentence. Writing phrases phonetically will also help students understand liaison, or how words blend together.

- For example, when the same consonant ends 1 word and begins another, it’s usually only pronounced once: “Sam made that,” or “Sammade that.” A consonant at the end of a word usually blends with the vowel that begins the next word: “Sam made that at school,” or “Sammade thatat school.”[14]

-

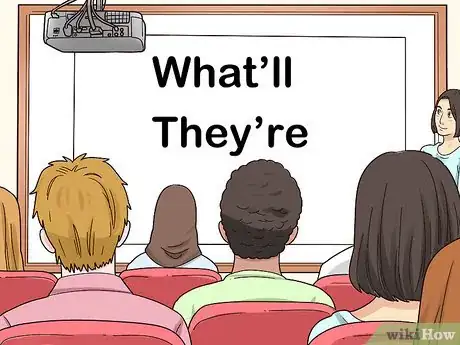

3Use listening exercises to help students recognize contractions. Play a variety of movie clips, radio and television programs, podcasts, and other media. Choose examples that frequently use contractions. After playing a short sample, have students identify which contractions they heard.[15]

- Students might easily recognize “what’ll” or “they’re” in writing. However, it’s more difficult to understand contractions during an actual conversation.

-

4Play recordings to expose students to slang and idioms. In addition to contractions, slang and idioms can pose significant challenges to ESL learners. Use a range of media examples to provide students with an assortment of individual and regional language quirks.To assess their understanding, try playing 1 part of a recorded conversation, then have students respond using their own words.[16]

- Pronunciation is usually taught with clear examples and written texts. However, students must learn how to recognize the spontaneous speech habits of native English speakers in order to master conversational skills.

- Some early lessons you should teach ESL students are pronouns and basic vocabulary. For example, family members, animals, numbers, and basic actions.

- They should learn to build a basic sentence.

- And also know about the present simple, past simple, and future simple tense.

References

- ↑ http://web.ntpu.edu.tw/~language/workshop/phonics.pdf

- ↑ https://www.press.umich.edu/pdf/0472031341-sample2.pdf

- ↑ http://esl.yourdictionary.com/esl/esl-lessons-and-materials/tips-resources-for-teaching-esl-pronunciation.html

- ↑ http://esl.yourdictionary.com/esl/esl-lessons-and-materials/tips-resources-for-teaching-esl-pronunciation.html

- ↑ http://www.ameprc.mq.edu.au/docs/fact_sheets/03Pronunciation.pdf

- ↑ https://bayanebartar.org/file-dl/library/IELTS8/American-Accent-Training/American-Accent-Training.pdf

- ↑ https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1078438.pdf

- ↑ http://esl.yourdictionary.com/esl/esl-lessons-and-materials/tips-resources-for-teaching-esl-pronunciation.html

- ↑ https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/using-intonation

- ↑ http://esl.yourdictionary.com/esl/esl-lessons-and-materials/tips-resources-for-teaching-esl-pronunciation.html

- ↑ http://esl.yourdictionary.com/esl/esl-lessons-and-materials/tips-resources-for-teaching-esl-pronunciation.html

- ↑ http://www.ameprc.mq.edu.au/docs/fact_sheets/03Pronunciation.pdf

- ↑ http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/learningenglish/pronunciation/pdf/exercises/schwa_exercises.pdf

- ↑ http://esl.yourdictionary.com/esl/esl-lessons-and-materials/tips-resources-for-teaching-esl-pronunciation.html

- ↑ https://helenslanguagehome.com/my-language-blog/listening-contractions-spoken-english/

- ↑ https://library.nwacc.edu/esol/websites