Abrahamic religions

The Abrahamic religions are a group of religions, most notably Judaism, Christianity and Islam, centered around the worship of the God of Abraham. Abraham, a Hebrew patriarch, is extensively mentioned in the religious scriptures of the Hebrew and Christian Bibles, and the Quran.[1]

Jewish tradition claims that the Twelve Tribes of Israel are descended from Abraham through his son Isaac and grandson Jacob, whose sons formed the nation of the Israelites in Canaan; Islamic tradition claims that twelve Arab tribes known as the Ishmaelites are descended from Abraham through his son Ishmael in the Arabian Peninsula.[2]

In its early stages, the Israelite religion was derived from the Canaanite religions of the Bronze Age; by the Iron Age, it had become distinct from other Canaanite religions as it shed polytheism for monolatry. The monolatrist nature of Yahwism was further developed in the period following the Babylonian captivity, eventually emerging as a firm religious movement of monotheism.[3][4][5] In the 1st century AD, Christianity emerged as a splinter movement out of Judaism in the Land of Israel, developed under the Apostles of Jesus of Nazareth;[6] it spread widely after it was adopted by the Roman Empire as a state religion in the 4th century AD. In the 7th century AD, Islam was founded by Muhammad in the Arabian Peninsula; it spread widely through the early Muslim conquests, shortly after his death.[6]

Alongside the Indian religions, the Iranian religions, and the East Asian religions, the Abrahamic religions make up the largest major division in comparative religion.[7] By total number of adherents, Christianity and Islam comprise the largest and second-largest religious movements in the world, respectively.[8] Abrahamic religions with fewer adherents include Judaism, the Baháʼí Faith, Druzism, Samaritanism, and Rastafari.[9]

Etymology

The Catholic scholar of Islam Louis Massignon stated that the phrase "Abrahamic religion" means that all these religions come from one spiritual source.[10] The modern term comes from the plural form of a Quranic reference to dīn Ibrāhīm, 'religion of Ibrahim', Arabic form of Abraham's name.[11]

God's promise at Genesis 15:4–8 regarding Abraham's heirs became paradigmatic for Jews, who speak of him as "our father Abraham" (Avraham Avinu). With the emergence of Christianity, Paul the Apostle, in Romans 4:11–12, likewise referred to him as "father of all" those who have faith, circumcised or uncircumcised. Islam likewise conceived itself as the religion of Abraham.[12] All the major Abrahamic religions claim a direct lineage to Abraham:

- Abraham is recorded in the Torah as the ancestor of the Israelites through his son Isaac, born to Sarah through a promise made in Genesis.[13][14]

- Christians affirm the ancestral origin of the Jews in Abraham.[12] Christianity also claims that Jesus was descended from Abraham.[15]

- Muhammad, as an Arab, is believed by Muslims to be descended from Abraham's son Ishmael, through Hagar. Jewish tradition also equates the descendants of Ishmael, Ishmaelites, with Arabs, while the descendants of Isaac by Jacob, who was also later known as Israel, are the Israelites.[16]

- The Bahá'í Faith states in its scripture that Bahá'ullah descended from Abraham through his wife Keturah's sons.[6][17][18]

Debates regarding the term

The appropriateness of grouping Judaism, Christianity, and Islam by the terms "Abrahamic religions" or "Abrahamic traditions" has, at times, been challenged.[19] The common Christian beliefs of Incarnation, Trinity, and the resurrection of Jesus, for example, are not accepted by Judaism or Islam (see for example Islamic view of Jesus' death). There are key beliefs in both Islam and Judaism that are not shared by most of Christianity (such as abstinence from pork), and key beliefs of Islam, Christianity, and the Baháʼí Faith not shared by Judaism (such as the prophetic and Messianic position of Jesus, respectively).[20]

Adam Dodds argues that the term "Abrahamic faiths", while helpful, can be misleading, as it conveys an unspecified historical and theological commonality that is problematic on closer examination. While there is a commonality among the religions, in large measure their shared ancestry is peripheral to their respective foundational beliefs and thus conceals crucial differences.[21] Alan L. Berger, professor of Judaic Studies at Florida Atlantic University, wrote that although "Judaism birthed both Christianity and Islam", the three faiths "understand the role of Abraham" in different ways.[22] Aaron W. Hughes, meanwhile, describes the term as "imprecise" and "largely a theological neologism".[23]

An alternative designation for the "Abrahamic religions", "desert monotheism", may also have unsatisfactory connotations.[24]

Religions

Judaism

One of Judaism's primary texts is the Tanakh, an account of the Israelites' relationship with God from their earliest history until the building of the Second Temple (c. 535 BC). Abraham is hailed as the first Hebrew and the father of the Jewish people. One of his great-grandsons was Judah, from whom the religion ultimately gets its name. The Israelites were initially a number of tribes who lived in the Kingdom of Israel and Kingdom of Judah.

After being conquered and exiled, some members of the Kingdom of Judah eventually returned to Israel. They later formed an independent state under the Hasmonean dynasty in the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, before becoming a client kingdom of the Roman Empire, which also conquered the state and dispersed its inhabitants. From the 2nd to the 6th centuries, Rabbinical Jews (believed to be descended from the historical Pharisees) wrote the Talmud, a lengthy work of legal rulings and Biblical exegesis which, along with the Tanakh, is a key text of Rabbinical Judaism.[25] Karaite Jews (believed to be descended from the Sadducees) and the Beta Israel reject the Talmud and the idea of an Oral Torah, following the Tanakh only.[26]

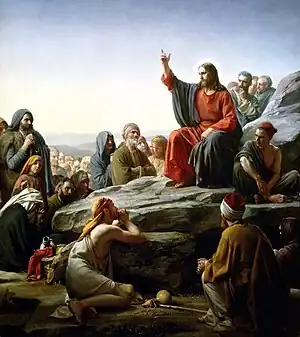

Christianity

Christianity began in the 1st century as a sect within Judaism initially led by Jesus. His followers viewed him as the Messiah, as in the Confession of Peter; after his crucifixion and death they came to view him as God incarnate,[27] who was resurrected and will return at the end of time to judge the living and the dead and create an eternal Kingdom of God. Within a few decades the new movement split from Judaism. Christian teaching is based on the Old and New Testaments of the Bible.

After several periods of alternating persecution and relative peace vis-à-vis the Roman authorities under different administrations, Christianity became the state church of the Roman Empire in 380, but has been split into various churches from its beginning. An attempt was made by the Byzantine Empire to unify Christendom, but this formally failed with the East–West Schism of 1054. In the 16th century, the birth and growth of Protestantism during the Reformation further split Christianity into many denominations. The largest post-Reformation branching is the Latter Day Saint movement.

Islam

Islam is based on the teachings of the Quran. Although it considers Muhammad to be the Seal of the prophets, Islam teaches that every prophet preached Islam, as the word Islam literally means submission, the main concept preached by all Abrahamic prophets. Although the Quran is the central religious text of Islam, which Muslims believe to be a revelation from God,[28] other Islamic books considered to be revealed by God before the Quran, mentioned by name in the Quran are the Tawrat (Torah) revealed to the prophets and messengers amongst the Children of Israel, the Zabur (Psalms) revealed to Dawud (David) and the Injil (the Gospel) revealed to Isa (Jesus). The Quran also mentions God having revealed the Scrolls of Abraham and the Scrolls of Moses.

The teachings of the Quran are believed by Muslims to be the direct and final revelation and words of God. Islam, like Christianity, is a universal religion (i.e. membership is open to anyone). Like Judaism, it has a strictly unitary conception of God, called tawhid, or "strict" monotheism.[29]

Other Abrahamic religions

Historically, the Abrahamic religions have been considered to be Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.[9] Some of this is due to the age and larger size of these three.[9] The other, similar religions were seen as either too new to judge as being truly in the same class, or too small to be of significance to the category.

However, some of the restrictions of Abrahamic to these three is due only to tradition in historical classification. Therefore, restricting the category to these three religions has come under criticism.[30][31] The religions listed below here claim Abrahamic classification, either by the religions themselves, or by scholars who study them.

Baháʼí Faith

The Baháʼí Faith, which developed from Shi'a Islam during the late 19th century, is a world religion that has been listed as Abrahamic by scholarly sources in various fields.[32][33] Monotheistic, it recognizes Abraham as one of a number of Manifestations of God[34] including Adam, Moses, Zoroaster, Krishna, Gautama Buddha, Jesus, Muhammad, the Báb, and ultimately Baháʼu'lláh.[35] God communicates his will and purpose to humanity through these intermediaries, in a process known as progressive revelation. [36][35]

Druzism

_-_Nebi_Shueib_Festival.jpg.webp)

The Druze faith or Druzism is a monotheistic religion based on the teachings of high Islamic figures like Hamza ibn-'Ali ibn-Ahmad and Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, and Greek philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle.[37][lower-alpha 1]

The Epistles of Wisdom is the foundational text of the Druze faith.[41] The Druze faith incorporates elements of Islam's Ismailism,[42] Gnosticism,[43][44] Neoplatonism,[43][44] Pythagoreanism,[45][46] Christianity,[43][44] Hinduism[45][46] and other philosophies and beliefs, creating a distinct and secretive theology known to interpret esoterically religious scriptures, and to highlight the role of the mind and truthfulness.[46] The Druze follow theophany,[47] and believe in reincarnation or the transmigration of the soul.[48] At the end of the cycle of rebirth, which is achieved through successive reincarnations, the soul is united with the Cosmic Mind (Al Aaqal Al Kulli).[49] In the Druze faith, Jesus is considered one of God's important prophets.[50][51]

Rastafari

The heterogeneous Rastafari movement, sometimes termed Rastafarianism, which originated in Jamaica is classified by some scholars as an international socio-religious movement, and by others as a separate Abrahamic religion.[52] Classified as both a new religious movement and social movement, it developed in Jamaica during the 1930s.[52] It lacks any centralised authority and there is much heterogeneity among practitioners, who are known as Rastafari, Rastafarians, or Rastas.[52]

Rastafari refer to their beliefs, which are based on a specific interpretation of the Bible, as "Rastalogy". Central is a monotheistic belief in a single God—referred to as Jah—who partially resides within each individual.[52] The former Emperor of Ethiopia, Haile Selassie, is given central importance; many Rastas regard him as the returned Messiah, the incarnation of Jah on Earth, and as the Second Coming of Christ.[52] Others regard him as a human prophet who fully recognised the inner divinity within every individual. Rastafari is Afrocentric and focuses its attention on the African diaspora, which it believes is oppressed within Western society, or "Babylon".[52] Many Rastas call for the resettlement of the African diaspora in either Ethiopia or Africa more widely, referring to this continent as the Promised Land of "Zion".[52] Other interpretations shift focus on to the adoption of an Afrocentric attitude while living outside of Africa. Rastas refer to their practices as "livity".[52] Communal meetings are known as "groundations", and are typified by music, chanting, discussions, and the smoking of cannabis, the latter being regarded as a sacrament with beneficial properties.[52] Rastas place emphasis on what they regard as living 'naturally', adhering to ital dietary requirements, allowing their hair to form into dreadlocks, and following patriarchal gender roles.[52]

Samaritanism

The Samaritans adhere to the Samaritan Torah, which they believe is the original, unchanged Torah,[53] as opposed to the Torah used by Jews. In addition to the Samaritan Torah, Samaritans also revere their version of the Book of Joshua and recognize some later Biblical figures such as Eli.

Samaritanism is internally described as the religion that began with Moses, unchanged over the millennia that have since passed. Samaritans believe Judaism and the Jewish Torah have been corrupted by time and no longer serve the duties God mandated on Mount Sinai. While Jews view the Temple Mount in Jerusalem as the most sacred location in their faith, Samaritans regard Mount Gerizim, near Nablus, as the holiest spot on Earth.

Other Samaritan religious works include the Memar Markah, the Samaritan liturgy, and Samaritan law codes and biblical commentaries; scholars have various theories concerning the actual relationships between these three texts. The Samaritan Pentateuch first became known to the Western world in 1631, proving the first example of the Samaritan alphabet and sparking an intense theological debate regarding its relative age versus the Masoretic Text.[54]

Mandaeism

Mandaeism (Classical Mandaic: ࡌࡀࡍࡃࡀࡉࡉࡀ mandaiia; Arabic: المندائيّة al-Mandāʾiyya), sometimes also known as Nasoraeanism or Sabianism,[lower-alpha 2] is a Gnostic, monotheistic and ethnic religion.[55]: 4 [56]: 1 Its adherents, the Mandaeans, revere Adam, Abel, Seth, Enos, Noah, Shem, Aram, and especially John the Baptist. Mandaeans consider Adam, Seth, Noah, Shem and John the Baptist prophets, with Adam being the founder of the religion and John being the greatest and final prophet.[57]: 45 [58]

The Mandaeans speak an Eastern Aramaic language known as Mandaic. The name 'Mandaean' comes from the Aramaic manda, meaning knowledge.[59][60] Within the Middle East, but outside their community, the Mandaeans are more commonly known as the صُبَّة Ṣubba (singular: Ṣubbī), or as Sabians (الصابئة, al-Ṣābiʾa). The term Ṣubba is derived from an Aramaic root related to baptism.[61] The term Sabians derives from the mysterious religious group mentioned three times in the Quran. The name of this unidentified group, which is implied in the Quran to belong to the 'People of the Book' (ahl al-kitāb), was historically claimed by the Mandaeans as well as by several other religious groups in order to gain legal protection (dhimma) as offered by Islamic law.[62] Occasionally, Mandaeans are also called "Christians of Saint John".[63]

Origins and history

The civilizations that developed in Mesopotamia influenced some religious texts, particularly the Hebrew Bible and the Book of Genesis. Abraham is said to have originated in Mesopotamia.[64]

Judaism regards itself as the religion of the descendants of Jacob,[lower-alpha 3] a grandson of Abraham. It has a strictly unitary view of God, and the central holy book for almost all branches is the Masoretic Text as elucidated in the Oral Torah. In the 19th century and 20th centuries Judaism developed a small number of branches, of which the most significant are Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform.

Christianity began as a sect of Judaism[lower-alpha 4] in the Mediterranean Basin[lower-alpha 5] of the first century CE and evolved into a separate religion—Christianity—with distinctive beliefs and practices. Jesus is the central figure of Christianity, considered by almost all denominations to be God the Son, one person of the Trinity. (See God in Christianity.[lower-alpha 6]) The Christian biblical canons are usually held to be the ultimate authority, alongside sacred tradition in some denominations (such as the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church). Over many centuries, Christianity divided into three main branches (Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant), dozens of significant denominations, and hundreds of smaller ones.

Islam arose in the Arabian Peninsula in the 7th century CE with a strictly unitary view of God.[lower-alpha 7] Muslims hold the Quran to be the ultimate authority, as revealed and elucidated through the teachings and practices[lower-alpha 8] of a central, but not divine, prophet, Muhammad. The Islamic faith considers all prophets and messengers from Adam through the final messenger (Muhammad) to carry the same Islamic monotheistic principles. Soon after its founding, Islam split into two main branches (Sunni and Shia Islam), each of which now has a number of denominations.

The Baháʼí Faith began within the context of Shia Islam in 19th-century Persia, after a merchant named Siyyid 'Alí Muḥammad Shírází claimed divine revelation and took on the title of the Báb, or "the Gate". The Báb's ministry proclaimed the imminent advent of "He whom God shall make manifest", who Baháʼís accept as Bahá'u'lláh. Baháʼís revere the Torah, Gospels and the Quran, and the writings of the Báb, Bahá'u'lláh, and Abdu'l-Bahá are considered the central texts of the faith. A vast majority of adherents are unified under a single denomination.[65]

Common aspects

All Abrahamic religions accept the tradition that God revealed himself to the patriarch Abraham.[66] All of them are monotheistic, and all of them conceive God to be a transcendent creator and the source of moral law.[67] Their religious texts feature many of the same figures, histories, and places, although they often present them with different roles, perspectives, and meanings.[68] Believers who agree on these similarities and the common Abrahamic origin tend to also be more positive towards other Abrahamic groups.[69]

In the three main Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity and Islam), the individual, God, and the universe are highly separate from each other. The Abrahamic religions believe in a judging, paternal, fully external god to which the individual and nature are both subordinate. One seeks salvation or transcendence not by contemplating the natural world or via philosophical speculation, but by seeking to please God (such as obedience with God's wishes or his law) and see divine revelation as outside of self, nature, and custom.

Monotheism

All Abrahamic religions claim to be monotheistic, worshiping an exclusive God, although one who is known by different names.[66] Each of these religions preaches that God creates, is one, rules, reveals, loves, judges, punishes, and forgives.[21] However, although Christianity does not profess to believe in three gods—but rather in three persons, or hypostases, united in one essence—the Trinitarian doctrine, a fundamental of faith for the vast majority of Christian denominations,[70][71] conflicts with Jewish and Muslim concepts of monotheism. Since the conception of a divine Trinity is not amenable to tawhid, the Islamic doctrine of monotheism, Islam regards Christianity as variously polytheistic.[72]

Christianity and Islam both revere Jesus (Arabic: Isa or Yasu among Muslims and Arab Christians respectively) but with vastly differing conceptions:

- Christians view Jesus as the saviour and regard him as God incarnate.

- Muslims see Isa as a Prophet of Islam[73] and Messiah.

However, the worship of Jesus, or the ascribing of partners to God (known as shirk in Islam and as shituf in Judaism), is typically viewed as the heresy of idolatry by Islam and Judaism.

Theological continuity

All the Abrahamic religions affirm one eternal God who created the universe, who rules history, who sends prophetic and angelic messengers and who reveals the divine will through inspired revelation. They also affirm that obedience to this creator deity is to be lived out historically and that one day God will unilaterally intervene in human history at the Last Judgment. Christianity, Islam, and Judaism have a teleological view on history, unlike the static or cyclic view on it found in other cultures[74] (the latter being common in Indian religions).

Scriptures

All Abrahamic religions believe that God guides humanity through revelation to prophets, and each religion believes that God revealed teachings to prophets, including those prophets whose lives are documented in its own scripture.

Ethical orientation

An ethical orientation: all these religions speak of a choice between good and evil, which is associated with obedience or disobedience to a single God and to Divine Law.

Eschatological world view

An eschatological world view of history and destiny, beginning with the creation of the world and the concept that God works through history, and ending with a resurrection of the dead and final judgment and world to come.[75]

Importance of Jerusalem

Jerusalem is considered Judaism's holiest city. Its origins can be dated to 1004 BCE,[76] when according to Biblical tradition David established it as the capital of the United Kingdom of Israel, and his son Solomon built the First Temple on Mount Moriah.[77] Since the Hebrew Bible relates that Isaac's sacrifice took place there, Mount Moriah's importance for Jews predates even these prominent events. Jews thrice daily pray in its direction, including in their prayers pleas for the restoration and the rebuilding of the Holy Temple (the Third Temple) on mount Moriah, close the Passover service with the wistful statement "Next year in built Jerusalem," and recall the city in the blessing at the end of each meal. Jerusalem has served as the only capital for the five Jewish states that have existed in Israel since 1400 BCE (the United Kingdom of Israel, the Kingdom of Judah, Yehud Medinata, the Hasmonean Kingdom, and modern Israel). It has been majority Jewish since about 1852 and continues through today.[78][79]

Jerusalem was an early center of Christianity. There has been a continuous Christian presence there since.[80] William R. Kenan, Jr., professor of the history of Christianity at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, writes that from the middle of the 4th century to the Islamic conquest in the middle of the 7th century, the Roman province of Palestine was a Christian nation with Jerusalem its principal city.[80] According to the New Testament, Jerusalem was the city Jesus was brought to as a child to be presented at the temple[81] and for the feast of the Passover.[82] He preached and healed in Jerusalem, unceremoniously drove the money changers in disarray from the temple there, held the Last Supper in an "upper room" (traditionally the Cenacle) there the night before he was crucified on the cross and was arrested in Gethsemane. The six parts to Jesus' trial—three stages in a religious court and three stages before a Roman court—were all held in Jerusalem. His crucifixion at Golgotha, his burial nearby (traditionally the Church of the Holy Sepulchre), and his resurrection and ascension and prophecy to return all are said to have occurred or will occur there.

Jerusalem became holy to Muslims, third after Mecca and Medina. The Al-Aqsa, which translates to "farthest mosque" in sura Al-Isra in the Quran and its surroundings are addressed in the Quran as "the holy land". Muslim tradition as recorded in the ahadith identifies al-Aqsa with a mosque in Jerusalem. The first Muslims did not pray toward Kaaba, but toward Jerusalem. The qibla was switched to Kaaba later on to fulfill the order of Allah of praying in the direction of Kaaba (Quran, Al-Baqarah 2:144–150). Another reason for its significance is its connection with the Miʿrāj,[83] where, according to traditional Muslim, Muhammad ascended through the Seven heavens on a winged mule named Buraq, guided by the Archangel Gabriel, beginning from the Foundation Stone on the Temple Mount, in modern times under the Dome of the Rock.[84][85]

Significance of Abraham

Even though members of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam do not all claim Abraham as an ancestor, some members of these religions have tried to claim him as exclusively theirs.[32]

For Jews, Abraham is the founding patriarch of the children of Israel. God promised Abraham: "I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you."[87] With Abraham, God entered into "an everlasting covenant throughout the ages to be God to you and to your offspring to come".[88] It is this covenant that makes Abraham and his descendants children of the covenant. Similarly, converts, who join the covenant, are all identified as sons and daughters of Abraham.

Abraham is primarily a revered ancestor or patriarch (referred to as Avraham Avinu (אברהם אבינו in Hebrew) "Abraham our father") to whom God made several promises: chiefly, that he would have numberless descendants, who would receive the land of Canaan (the "Promised Land"). According to Jewish tradition, Abraham was the first post-Flood prophet to reject idolatry through rational analysis, although Shem and Eber carried on the tradition from Noah.[89][90]

Christians view Abraham as an important exemplar of faith, and a spiritual, as well as physical, ancestor of Jesus. For Christians, Abraham is a spiritual forebear as well as/rather than a direct ancestor depending on the individual's interpretation of Paul the Apostle,[91] with the Abrahamic covenant "reinterpreted so as to be defined by faith in Christ rather than biological descent" or both by faith as well as a direct ancestor; in any case, the emphasis is placed on faith being the only requirement for the Abrahamic Covenant to apply[92] (see also New Covenant and supersessionism). In Christian belief, Abraham is a role model of faith,[93] and his obedience to God by offering Isaac is seen as a foreshadowing of God's offering of his son Jesus.[94][95]

Christian commentators have a tendency to interpret God's promises to Abraham as applying to Christianity subsequent to, and sometimes rather than (as in supersessionism), being applied to Judaism, whose adherents rejected Jesus. They argue this on the basis that just as Abraham as a Gentile (before he was circumcised) "believed God and it was credited to him as righteousness" [96] (cf. Rom. 4:3, James 2:23), "those who have faith are children of Abraham" [97] (see also John 8:39). This is most fully developed in Paul's theology where all who believe in God are spiritual descendants of Abraham.[98][lower-alpha 9] However, with regards to Rom. 4:20[99] and Gal. 4:9,[100] in both cases he refers to these spiritual descendants as the "sons of God"[101] rather than "children of Abraham".[102]

For Muslims, Abraham is a prophet, the "messenger of God" who stands in the line from Adam to Muhammad, to whom God gave revelations,[Quran %3Averse%3D163 4 :163], who "raised the foundations of the House" (i.e., the Kaaba)[Quran %3Averse%3D127 2 :127] with his first son, Isma'il, a symbol of which is every mosque.[103] Ibrahim (Abraham) is the first in a genealogy for Muhammad. Islam considers Abraham to be "one of the first Muslims" (Surah 3)—the first monotheist in a world where monotheism was lost, and the community of those faithful to God,[104] thus being referred to as ابونا ابراهيم or "Our Father Abraham", as well as Ibrahim al-Hanif or "Abraham the Monotheist". Also, the same as Judaism, Islam believes that Abraham rejected idolatry through logical reasoning. Abraham is also recalled in certain details of the annual Hajj pilgrimage.[105]

Differences

God

The Abrahamic God is the conception of God that remains a common feature of all Abrahamic religions.[106] The Abrahamic God is conceived of as eternal, omnipotent, omniscient and as the creator of the universe.[106] God is further held to have the properties of holiness, justice, omnibenevolence, and omnipresence.[106] Proponents of Abrahamic faiths believe that God is also transcendent, but at the same time personal and involved, listening to prayer and reacting to the actions of his creatures. God in Abrahamic religions is always referred to as masculine only.[106]

Jewish theology is strictly monotheistic. God is an absolute one, indivisible and incomparable being who is the ultimate cause of all existence. Jewish tradition teaches that the true aspect of God is incomprehensible and unknowable and that it is only God's revealed aspect that brought the universe into existence, and interacts with mankind and the world. In Judaism, the one God of Israel is the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, who is the guide of the world, delivered Israel from slavery in Egypt, and gave them the 613 Mitzvot at Mount Sinai as described in the Torah.

The national god of the Israelites has a proper name, written Y-H-W-H (Hebrew: יהוה) in the Hebrew Bible. The etymology of the name is unknown.[107] An explanation of the name is given to Moses when YHWH calls himself "I Am that I Am", (Hebrew: אהיה אשר אהיה ’ehye ’ăšer ’ehye), seemingly connecting it to the verb hayah (הָיָה), meaning 'to be', but this is likely not a genuine etymology. Jewish tradition accords many names to God, including Elohim, Shaddai, and Sabaoth.

In Christian theology, God is the eternal being who created and preserves the world. Christians believe God to be both transcendent and immanent (involved in the world).[108][109] Early Christian views of God were expressed in the Pauline Epistles and the early[lower-alpha 10] creeds, which proclaimed one God and the divinity of Jesus.

Around the year 200, Tertullian formulated a version of the doctrine of the Trinity which clearly affirmed the divinity of Jesus and came close to the later definitive form produced by the Ecumenical Council of 381.[110][111] Trinitarians, who form the large majority of Christians, hold it as a core tenet of their faith.[112][113] Nontrinitarian denominations define the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit in a number of different ways.[114]

The theology of the attributes and nature of God has been discussed since the earliest days of Christianity, with Irenaeus writing in the 2nd century: "His greatness lacks nothing, but contains all things."[115] In the 8th century, John of Damascus listed eighteen attributes which remain widely accepted.[116] As time passed, theologians developed systematic lists of these attributes, some based on statements in the Bible (e.g., the Lord's Prayer, stating that the Father is in Heaven), others based on theological reasoning.[117][118]

In Islamic theology, God (Arabic: الله Allāh) is the all-powerful and all-knowing creator, sustainer, ordainer and judge of everything in existence.[119] Islam emphasizes that God is strictly singular (tawḥīd)[120] unique (wāḥid) and inherently One (aḥad), all-merciful and omnipotent.[121] According to Islamic teachings, God exists without place[122] and according to the Quran, "No vision can grasp him, but His grasp is over all vision: He is above all comprehension, yet is acquainted with all things."[123] God, as referenced in the Quran, is the only God.[124][125] Islamic tradition also describes the 99 names of God. These 99 names describe attributes of God, including Most Merciful, The Just, The Peace and Blessing, and the Guardian.

Islamic belief in God is distinct from Christianity in that God has no progeny. This belief is summed up in chapter 112 of the Quran titled Al-Ikhlas, which states "Say, he is Allah (who is) one, Allah is the Eternal, the Absolute. He does not beget nor was he begotten. Nor is there to Him any equivalent."[Quran %3Averse%3D1 112 :1]

Scriptures

All these religions rely on a body of scriptures, some of which are considered to be the word of God—hence sacred and unquestionable—and some the work of religious men, revered mainly by tradition and to the extent that they are considered to have been divinely inspired, if not dictated, by the divine being.

The sacred scriptures of Judaism are the Tanakh, a Hebrew acronym standing for Torah (Law or Teachings), Nevi'im (Prophets) and Ketuvim (Writings). These are complemented by and supplemented with various (originally oral) traditions: Midrash, the Mishnah, the Talmud and collected rabbinical writings. The Tanakh (or Hebrew Bible) was composed between 1,400 BCE, and 400 BCE by Jewish prophets, kings, and priests.

The Hebrew text of the Tanakh, and the Torah in particular is considered holy, down to the last letter: transcribing is done with painstaking care. An error in a single letter, ornamentation or symbol of the 300,000+ stylized letters that make up the Hebrew Torah text renders a Torah scroll unfit for use; hence the skills of a Torah scribe are specialist skills, and a scroll takes considerable time to write and check.

The sacred scriptures of most Christian groups are the Old Testament and the New Testament. Latin Bibles originally contained 73 books; however, 7 books, collectively called the Apocrypha or Deuterocanon depending on one's opinion of them, were removed by Martin Luther due to a lack of original Hebrew sources, and now vary on their inclusion between denominations. Greek Bibles contain additional materials.

The New Testament comprises four accounts of the life and teachings of Jesus (the Four Gospels), as well as several other writings (the epistles) and the Book of Revelation. They are usually considered to be divinely inspired, and together comprise the Christian Bible.

The vast majority of Christian faiths (including Catholicism, Orthodox Christianity, and most forms of Protestantism) recognize that the Gospels were passed on by oral tradition, and were not set to paper until decades after the resurrection of Jesus and that the extant versions are copies of those originals. The version of the Bible considered to be most valid (in the sense of best conveying the true meaning of the word of God) has varied considerably: the Greek Septuagint, the Syriac Peshitta, the Latin Vulgate, the English King James Version and the Russian Synodal Bible have been authoritative to different communities at different times.

The sacred scriptures of the Christian Bible are complemented by a large body of writings by individual Christians and councils of Christian leaders (see canon law). Some Christian churches and denominations consider certain additional writings to be binding; other Christian groups consider only the Bible to be binding (sola scriptura).

Islam's holiest book is the Quran, comprising 114 Suras ("chapters of the Qur'an"). However, Muslims also believe in the religious texts of Judaism and Christianity in their original forms, albeit not the current versions. According to the Quran (and mainstream Muslim belief), the verses of the Quran were revealed by God through the Archangel Jibrail to Muhammad on separate occasions. These revelations were written down and also memorized by hundreds of companions of Muhammad. These multiple sources were collected into one official copy. After the death of Muhammad, Quran was copied on several copies and Caliph Uthman provided these copies to different cities of Islamic Empire.

The Quran mentions and reveres several of the Israelite prophets, including Moses and Jesus, among others (see also: Prophets of Islam). The stories of these prophets are very similar to those in the Bible. However, the detailed precepts of the Tanakh and the New Testament are not adopted outright; they are replaced by the new commandments accepted as revealed directly by God (through Gabriel) to Muhammad and codified in the Quran.

Like the Jews with the Torah, Muslims consider the original Arabic text of the Quran as uncorrupted and holy to the last letter, and any translations are considered to be interpretations of the meaning of the Quran, as only the original Arabic text is considered to be the divine scripture.[126]

Like the Rabbinic Oral Law to the Hebrew Bible, the Quran is complemented by the Hadith, a set of books by later authors recording the sayings of the prophet Muhammad. The Hadith interpret and elaborate Qur'anic precepts. Islamic scholars have categorized each Hadith at one of the following levels of authenticity or isnad: genuine (sahih), fair (hasan) or weak (da'if).[127]

Circumcision

Judaism and Samaritanism commands that males be circumcised when they are eight days old,[128] as does the Sunnah in Islam. Despite its common practice in Muslim-majority nations, circumcision is considered to be sunnah (tradition) and not required for a life directed by Allah.[129] Although there is some debate within Islam over whether it is a religious requirement or mere recommendation, circumcision (called khitan) is practiced nearly universally by Muslim males.

Today, many Christian denominations are neutral about ritual male circumcision, not requiring it for religious observance, but neither forbidding it for cultural or other reasons.[130] Western Christianity replaced the custom of male circumcision with the ritual of baptism,[131] a ceremony which varies according to the doctrine of the denomination, but it generally includes immersion, aspersion, or anointment with water. The Early Church (Acts 15, the Council of Jerusalem) decided that Gentile Christians are not required to undergo circumcision. The Council of Florence in the 15th century[132] prohibited it. Paragraph #2297 of the Catholic Catechism calls non-medical amputation or mutilation immoral.[133][134] By the 21st century, the Catholic Church had adopted a neutral position on the practice, as long as it is not practised as an initiation ritual. Catholic scholars make various arguments in support of the idea that this policy is not in contradiction with the previous edicts.[135][136][137] The New Testament chapter Acts 15 records that Christianity did not require circumcision. The Catholic Church currently maintains a neutral position on the practice of non-religious circumcision,[138] and in 1442 it banned the practice of religious circumcision in the 11th Council of Florence.[139] Coptic Christians practice circumcision as a rite of passage.[140] The Eritrean Orthodox Church and the Ethiopian Orthodox Church calls for circumcision, with near-universal prevalence among Orthodox men in Ethiopia.[141]

Many countries with majorities of Christian adherents in Europe and Latin America have low circumcision rates, while both religious and non-religious circumcision is widely practiced in many predominantly Christian countries and among Christian communities in the Anglosphere countries, Oceania, South Korea, the Philippines, the Middle East and Africa.[142][143] Countries such as the United States,[144] the Philippines, Australia (albeit primarily in the older generations),[145] Canada, Cameroon, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Equatorial Guinea, Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, and many other African Christian countries have high circumcision rates.[146][147][148] Circumcision is near universal in the Christian countries of Oceania.[143] In some African and Eastern Christian denominations male circumcision is an integral or established practice, and require that their male members undergo circumcision.[149] Coptic Christianity and Ethiopian Orthodoxy and Eritrean Orthodoxy still observe male circumcision and practice circumcision as a rite of passage.[140][150] Male circumcision is also widely practiced among Christians from South Korea, Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine, Israel, and North Africa. (See also aposthia.)

Male circumcision is among the rites of Islam and is part of the fitrah, or the innate disposition and natural character and instinct of the human creation.[151]

Circumcision is widely practiced by the Druze, the procedure is practiced as a cultural tradition,[152] and has no religious significance in the Druze faith.[153][154] Some Druses do not circumcise their male children, and refuse to observe this "common Muslim practice".[155]

Circumcision is not a religious practice of the Bahá'í Faith, and leaves that decision up to the parents.[156]

Dietary restrictions

Judaism and Islam have strict dietary laws, with permitted food known as kosher in Judaism, and halal in Islam. These two religions prohibit the consumption of pork; Islam prohibits the consumption of alcoholic beverages of any kind. Halal restrictions can be seen as a modification of the kashrut dietary laws, so many kosher foods are considered halal; especially in the case of meat, which Islam prescribes must be slaughtered in the name of God. Hence, in many places, Muslims used to consume kosher food. However, some foods not considered kosher are considered halal in Islam.[157]

With rare exceptions, Christians do not consider the Old Testament's strict food laws as relevant for today's church; see also Biblical law in Christianity. Most Protestants have no set food laws, but there are minority exceptions.[158]

The Catholic Church believes in observing abstinence and penance. For example, all Fridays through the year and the time of Lent are penitential days.[159] The law of abstinence requires a Catholic from 14 years of age until death to abstain from eating meat on Fridays in honor of the Passion of Jesus on Good Friday. The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops obtained the permission of the Holy See for Catholics in the U.S. to substitute a penitential, or even a charitable, practice of their own choosing.[160] Eastern Catholic Churches have their own penitential practices as specified by the Code of Canons for the Eastern Churches.

The Seventh-day Adventist Church (SDA) embraces numerous Old Testament rules and regulations such as tithing, Sabbath observance, and Jewish food laws. Therefore, they do not eat pork, shellfish, or other foods considered unclean under the Old Covenant. The "Fundamental Beliefs" of the SDA state that their members "are to adopt the most healthful diet possible and abstain from the unclean foods identified in the Scriptures".[161] among others[162]

In the Christian Bible, the consumption of strangled animals and of blood was forbidden by Apostolic Decree[163] and are still forbidden in the Greek Orthodox Church, according to German theologian Karl Josef von Hefele, who, in his Commentary on Canon II of the Second Ecumenical Council held in the 4th century at Gangra, notes: "We further see that, at the time of the Synod of Gangra, the rule of the Apostolic Synod [the Council of Jerusalem of Acts 15] with regard to blood and things strangled was still in force. With the Greeks, indeed, it continued always in force as their Euchologies still show." He also writes that "as late as the eighth century, Pope Gregory the Third, in 731, forbade the eating of blood or things strangled under threat of a penance of forty days."[164]

Jehovah's Witnesses abstain from eating blood and from blood transfusions based on Acts 15:19–21.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints prohibits the consumption of alcohol, coffee, and non-herbal tea. While there is not a set of prohibited food, the church encourages members to refrain from eating excessive amounts of red meat.[165]

Sabbath observance

Sabbath in the Bible is a weekly day of rest and time of worship. It is observed differently in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam and informs a similar occasion in several other Abrahamic faiths. Though many viewpoints and definitions have arisen over the millennia, most originate in the same textual tradition.

Proselytism

Judaism accepts converts, but has had no explicit missionaries since the end of the Second Temple era. Judaism states that non-Jews can achieve righteousness by following Noahide Laws, a set of moral imperatives that, according to the Talmud, were given by God[lower-alpha 11] as a binding set of laws for the "children of Noah"—that is, all of humanity.[166][lower-alpha 12] It is believed that as much as ten percent of the Roman Empire followed Judaism either as fully ritually obligated Jews or the simpler rituals required of non-Jewish members of that faith.[167]

Moses Maimonides, one of the major Jewish teachers, commented: "Quoting from our sages, the righteous people from other nations have a place in the world to come if they have acquired what they should learn about the Creator." Because the commandments applicable to the Jews are much more detailed and onerous than Noahide laws, Jewish scholars have traditionally maintained that it is better to be a good non-Jew than a bad Jew, thus discouraging conversion. In the U.S., as of 2003 28% of married Jews were married to non-Jews.[168] See also Conversion to Judaism.

Christianity encourages evangelism. Many Christian organizations, especially Protestant churches, send missionaries to non-Christian communities throughout the world. See also Great Commission. Forced conversions to Catholicism have been alleged at various points throughout history. The most prominently cited allegations are the conversions of the pagans after Constantine; of Muslims, Jews and Eastern Orthodox during the Crusades; of Jews and Muslims during the time of the Spanish Inquisition, where they were offered the choice of exile, conversion or death; and of the Aztecs by Hernán Cortés. Forced conversions to Protestantism may have occurred as well, notably during the Reformation, especially in England and Ireland (see recusancy and Popish plot).

Forced conversions are now condemned as sinful by major denominations such as the Roman Catholic Church, which officially states that forced conversions pollute the Christian religion and offend human dignity, so that past or present offences are regarded as a scandal (a cause of unbelief). According to Pope Paul VI, "It is one of the major tenets of Catholic doctrine that man's response to God in faith must be free: no one, therefore, is to be forced to embrace the Christian faith against his own will."[169] The Roman Catholic Church has declared that Catholics should fight anti-Semitism.[170]

Dawah is an important Islamic concept which denotes the preaching of Islam. Da‘wah literally means "issuing a summons" or "making an invitation". A Muslim who practices da‘wah, either as a religious worker or in a volunteer community effort, is called a dā‘ī, plural du‘āt. A dā‘ī is thus a person who invites people to understand Islam through a dialogical process and may be categorized in some cases as the Islamic equivalent of a missionary, as one who invites people to the faith, to the prayer, or to Islamic life.

Da'wah activities can take many forms. Some pursue Islamic studies specifically to perform Da'wah. Mosques and other Islamic centers sometimes spread Da'wah actively, similar to evangelical churches. Others consider being open to the public and answering questions to be Da'wah. Recalling Muslims to the faith and expanding their knowledge can also be considered Da'wah.

In Islamic theology, the purpose of Da'wah is to invite people, both Muslims and non-Muslims, to understand the commandments of God as expressed in the Quran and the Sunnah of the Prophet, as well as to inform them about Muhammad. Da'wah produces converts to Islam, which in turn grows the size of the Muslim Ummah, or community of Muslims.

Demographics

Worldwide percentage of adherents by Abrahamic religion, as of 2015[171]

Christianity is the largest Abrahamic religion with about 2.3 billion adherents, constituting about 31.1% of the world's population.[172] Islam is the second largest Abrahamic religion, as well as the fastest-growing Abrahamic religion in recent decades.[172][173] It has about 1.9 billion adherents, called Muslims, which constitute about 24.1% of the world's population. The third largest Abrahamic religion is Judaism with about 14.1 million adherents, called Jews.[172] The Baháʼí Faith has over 8 million adherents, making it the fourth largest Abrahamic religion,[174][175] and the fastest growing religion across the 20th century usually at least twice the rate of population growth.[176] The Druze Faith has between one million and nearly two millions adherents.[177][178]

| Religion | Adherents |

|---|---|

| Baháʼí | ~8 million[174][175] |

| Druze | 1–2 million[177][178] |

| Rastafari | 700,000-1 million[4] |

| Mandaeism | 60,000–100,000[16][179] |

| Azali Bábism | ~1,000–2,000[22][180] |

| Samaritanism | ~840[181] |

See also

- Abraham's family tree

- Abrahamic Family House, a complex in Abu Dhabi built in the spirit of Abrahamic unity

- Abrahamites

- Yahwism

- Ancient Semitic religion

- Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement

- Christianity and Islam

- Christianity and Judaism

- Christianity and other religions

- Gnosticism

- Interfaith dialogue

- Islamic–Jewish relations

- Islam and other religions

- Jewish views on religious pluralism

- Judeo-Christian ethics

- List of burial places of Abrahamic figures

- Mandaeism

- Messianism

- Manichaeism

- Yazidism

- Milah Abraham

- Nigerian Chrislam

- People of the Book

- Sabians

- Table of prophets of Abrahamic religions

- Zoroastrianism

Notes

- Hamza ibn Ali ibn Ahmad is considered the founder of the Druze and the primary author of the Druze manuscripts.[38] Jethro of Midian is considered an ancestor of Druze, who revere him as their spiritual founder and chief prophet.[39][40]

- The term 'Nasoraean' (lit. 'from Nazareth') is used for the initiated among the Mandaeans. For other religious groups sharing a similar name, see Nazarene (sect). The term 'Sabianism' is derived from the mysterious Sabians mentioned in the Quran, a name historically claimed by several religious groups. For other religions sometimes called 'Sabianism', see Sabians § Pagan Sabians.

- Jacob is also called Israel, a name the Bible states he was given by God.

- cf. Christianity in the 1st century, History of early Christianity, Judaizers, Paul the Apostle and Jewish Christianity, and Split of early Christianity and Judaism.

- With several centers, such as Rome, Jerusalem, Alexandria, Thessaloniki and Corinth, Antioch, and later spread outwards, eventually having two main centers in the empire, one for the Western Church and one for the Eastern Church in Rome and Constantinople respectively by the 5th century CE

- Triune God is also called the "Holy Trinity"

- The monotheistic view of God in Islam is called tawhid which is essentially the same as the conception of God in Judaism.

- Teachings and practices of Muhammad are collectively known as the sunnah, similar to the Judaic concepts of oral law and exegesis, or talmud and midrash.

- "So those who have faith are blessed along with Abraham, the man of faith." "In other words, it is not the children by physical descent who are God's children, but it is the children of the promise who are regarded as Abraham's offspring."Romans 9:8

- Perhaps even pre-Pauline creeds.

- According to Encyclopedia Talmudit (Hebrew edition, Israel, 5741/1981, Entry Ben Noah, page 349), most medieval authorities consider that all seven commandments were given to Adam, although Maimonides (Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot M'lakhim 9:1) considers the dietary law to have been given to Noah.

- Compare Genesis 9:4–6.

References

Citations

- Helm, Paul (2010). "Philosophy of Religion". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 21 July 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- Hatcher & Martin (1998), pp. 130–31; Bremer (2015), p. 19–20; Able (2011), p. 219; Dever (2001), pp. 97–102

- Edelman (1995), p. 19; Gnuse (2016), p. 5; Carraway (2013), p. 66: "Second, it was probably not until the exile that monotheism proper was clearly formulated."; Finkelstein & Silberman (2002), p. 234: "The idolatry of the people of Judah was not a departure from their earlier monotheism. It was, instead, the way the people of Judah had worshiped for hundreds of years."

- "BBC Two – Bible's Buried Secrets, Did God Have a Wife?". BBC. 21 December 2011. Archived from the original on 15 January 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2012. Quote from the BBC documentary (prof. Herbert Niehr): "Between the 10th century and the beginning of their exile in 586 there was polytheism as normal religion all throughout Israel; only afterwards things begin to change and very slowly they begin to change. I would say it [the sentence "Jews were monotheists" – n.n.] is only correct for the last centuries, maybe only from the period of the Maccabees, that means the second century BC, so in the time of Jesus of Nazareth it is true, but for the time before it, it is not true."

- Hayes, Christine (3 July 2008). "Moses and the Beginning of Yahwism: (Genesis 37- Exodus 4), Christine Hayes, Open Yale Courses (Transcription), 2006". Center for Online Judaic Studies. Archived from the original on 17 August 2022. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

Only later would a Yahweh-only party polemicize against and seek to suppress certain… what came to be seen as undesirable elements of Israelite-Judean religion, and these elements would be labeled Canaanite, as a part of a process of Israelite differentiation. But what appears in the Bible as a battle between Israelites, pure Yahwists, and Canaanites, pure polytheists, is indeed better understood as a civil war between Yahweh-only Israelites, and Israelites who are participating in the cult of their ancestors.

- Bremer 2015, p. 19-20.

- Adams 2007.

- Wormald 2015.

- Abulafia, Anna Sapir (23 September 2019). "The Abrahamic religions". London: British Library. Archived from the original on 12 July 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- Massignon 1949, pp. 20–23.

- Stroumsa 2017, p. 7.

- Levenson 2012, pp. 178–179.

- Gen. 17:16

- Scherman 2001, pp. 34–35.

- Matthew 1:1–17

- Saheeh al-Bukharee, Book 55, hadith no. 584; Book 56, hadith no. 710

- Able 2011, p. 219.

- Hatcher & Martin 1998, pp. 130–31.

- Boyd, Samuel L. (October 2019). "Judaism, Christianity, and Islam: The problem of 'Abrahamic religions' and the possibilities of comparison". Religion Compass. 13 (10). doi:10.1111/rec3.12339. S2CID 203090839.

- Greenstreet 2006, p. 95.

- Dodds 2009, pp. 230–253.

- "Dr. Alan L. Berger". Florida Atlantic University. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- Hughes 2012, pp. 3–4, 7–8, 17, 32.

- Benjamin 1983, p. 47, "Nineteenth century scholars were convinced that the uniform vastness of the desert was the incentive for Israel's belief in one god. Baly, however, points out that most desert dwellers are polytheists. ... Monotheism, according to Baly, have [sic] never developed in desert cultures; monotheism always develops in cities!".

- Strack, Hermann Leberecht; Stemberger, Gunter (1996). Introduction to the Talmud and Midrash. Fortress Press.

- Lichaa, Shawn (2022). "Karaite Judaism: An Introduction to its Theology and Practices". Routledge Handbook of Jewish Ritual and Practice (1 ed.). Routledge. pp. 179–192. doi:10.4324/9781003032823-15. ISBN 9781003032823.

- Pavlac, Brian A (2010). A Concise Survey of Western Civilization: Supremacies and Diversities. Chapter 6.

- Nasr, Seyyed Hossein (2007). "Qurʼān". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 4 November 2007.

- Religions » Islam » Islam at a glance Archived 21 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine, BBC, 5 August 2009.

-

- Micksch, Jürgen (2009). "Trialog International – Die jährliche Konferenz". Herbert Quandt Stiftung. Archived from the original on 23 May 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- Collins 2004, pp. 157, 160.

- Lubar Institute 2016.

- Beit-Hallahmi 1992, pp. 48–49.

- Smith 2008, p. 106.

- Cole 2012, pp. 438–446.

- Smith 2008, pp. 107–108.

- Dana (2010), p. 314; Morrison (2006), p. 259 Morrison (2006), p. 259; Lev (2010); Blumberg (1985), p. 201; Rosenfeld (1952), p. 290

- Hendrix & Okeja 2018, p. 11.

- Corduan 2013, p. 107.

- Mackey 2009, p. 28.

- Izzeddin 1993, pp. 108.

- Daftary 2013.

- Quilliam 1999, p. 42.

- New Encyclopaedia Britannica 1992, p. 237.

- Rosenthal 2003, p. 296.

- Kapur 2010.

- Swayd, SDSU, Dr. Samy, Druze Spirituality and Asceticism, Eial, archived from the original (an abridged rough draft; RTF) on 5 October 2006

- Nisan 2002, p. 95.

- "Druze". druze.org.au. 2015. Archived from the original on 14 February 2016.

- Hitti 1928, p. 37.

- Dana 2003, p. 17.

- Chryssides 2001, pp. 269–277.

- Tsedaka 2013.

- Florentin 2005.

- Buckley 2002.

- Al-Saadi, Qais; Al-Saadi, Hamed (2019). Ginza Rabba (2nd ed.). Germany: Drabsha.

- Brikhah S. Nasoraia (2012). "Sacred Text and Esoteric Praxis in Sabian Mandaean Religion" (PDF).

- mandaean الصابئة المندايين (21 November 2019). تعرف على دين المندايي في ثلاث دقائق. Retrieved 2 February 2022 – via YouTube.

- Rudolph 1977, p. 15.

- Fontaine, Petrus Franciscus Maria (January 1990). Dualism in ancient Iran, India and China. The Light and the Dark. Vol. 5. Brill. ISBN 9789050630511.

- Häberl 2009, p. 1

- De Blois 1960–2007; Van Bladel 2017, p. 5.

- Edmondo, Lupieri (2004). "Friar of Ignatius of Jesus (Carlo Leonelli) and the First 'Scholarly' Book on Mandaeaism (1652)". ARAM Periodical. 16 (Mandaeans and Manichaeans): 25–46. ISSN 0959-4213.

- Bertman 2005, p. 312.

- "The Baháʼí Faith – The website of the worldwide Baháʼí community". Bahai.org. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

The religions of the world come from the same Source and are in essence successive chapters of one religion from God.

- Peters 2018.

- "Religion: Three Religions – One God". Global Connections of the Middle East. WGBH Educational Foundation. 2002. Archived from the original on 17 September 2009. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- Kunst & Thomsen 2014, pp. 1–14.

- Kunst, Thomsen & Sam 2014, pp. 337–348.

- "The Trinity". BBC. July 2011. Archived from the original on 20 September 2018.

- Perman, Matt (January 2006). "What Is the Doctrine of the Trinity?". desiring God. Archived from the original on 30 October 2018.

- Hoover, Jon. "Islamic Monotheism and the Trinity" (PDF). University of Waterloo. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 January 2013.

- Rubin 2001.

- Huntington 2007, p. 337.

- Wiener, Philip P. Dictionary of the History of Ideas. Archived 21 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine Charles Scribner's Sons, 1973–74. The Electronic Text Center at the University of Virginia Library. Retrieved 4 August 2009.

- Tucker & Roberts 2008, p. 541.

- Fine 2011, pp. 302–303.

- Morgenstern 2006, p. 201.

- Lapidoth & Hirsch 1994, p. 384.

- Wilken 1986, p. 678.

- Luke 2:22

- Luke 2:41

- "Mi'raj – Islam". Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 26 October 2009.

- Perowne, Stewart Henry; Gordon, Buzzy; Prawer, Joshua; Dumper, Michael; Wasserstein, Bernard (13 August 2022). "Jerusalem". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 9 May 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- "Al-Aqsa Mosque – mosque, Jerusalem". Archived from the original on 18 January 2011. Retrieved 26 October 2009.

- Genesis 15

- Gen. 12:2

- Gen. 17:7

- Schultz 1975, pp. 51–52.

- Kaplan 1973, p. 161.

- Rom. 4:9–12

- Blasi, Turcotte, Duhaime, p. 592.

- Heb. 11:8–10

- Rom. 8:32

- MacArthur 1996.

- Gen. 15:6

- Gal. 3:7

- Rom. 4:20, Gal. 4:9

- Romans 4:20 King James Version (Oxford Standard, 1769)

- Galatians 4:9 King James Version (Oxford Standard, 1769)

- Gal. 4:26

- Bickerman, p. 188cf.

- Leeming 2005, p. 209.

- Fischer & Abedi 1990, pp. 163–166.

- Hawting 2006, pp. xviii, xix, xx, xxiii.

- Christiano, Kivisto & Swatos 2015, pp. 254–255.

- Hoffman, Joel (2004). In the Beginning: A Short History of the Hebrew Language. NYU Press. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-8147-3706-4. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- Leith 1993, pp. 55–56.

- Erickson 2001, pp. 87–88.

- Prestige 1963, p. 29.

- Kelly 2017, p. 119.

- Mills & Bullard 2001, p. 935.

- Kelly 2017, p. 23.

- McGrath 2012, pp. 117–120.

- Osborn 2001, pp. 27–29.

- Dyrness et al. 2008, pp. 352–353.

- Guthrie 1994, pp. 100, 111.

- Hirschberger, Johannes. Historia de la Filosofía I, Barcelona: Herder 1977, p. 403

- Böwering, Gerhard. "God and his Attributes". Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān. Brill. doi:10.1163/1875-3922_q3_eqcom_00075.

- Esposito 1999, p. 88.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 01 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 686–687.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 873.

- Quran %3Averse%3D103 6 :103

- Quran %3Averse%3D46 29 :46

- Peters 2003, p. 4.

- Baker & Saldanha 2008, p. 227.

- Ibn al-Ṣalāḥ 2006, p. 5.

- Mark 2003, pp. 94–95.

- Šakūrzāda, Ebrāhīm; Omidsalar, Mahmoud (October 2011). "Circumcision". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. V/6. New York: Columbia University. pp. 596–600. doi:10.1163/2330-4804_EIRO_COM_7731. ISSN 2330-4804. Archived from the original on 19 January 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- Pitts-Taylor 2008, p. 394.

- Kohler, Kaufmann; Krauss, Samuel. "Baptism". Jewish Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 31 August 2022. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

According to rabbinical teachings, which dominated even during the existence of the Temple (Pes. viii. 8), Baptism, next to circumcision and sacrifice, was an absolutely necessary condition to be fulfilled by a proselyte to Judaism (Yeb. 46b, 47b; Ker. 9a; 'Ab. Zarah 57a; Shab. 135a; Yer. Kid. iii. 14, 64d). Circumcision, however, was much more important, and, like baptism, was called a "seal" (Schlatter, "Die Kirche Jerusalems", 1898, p. 70). But as circumcision was discarded by Christianity, and the sacrifices had ceased, Baptism remained the sole condition for initiation into religious life. The next ceremony, adopted shortly after the others, was the imposition of hands, which, it is known, was the usage of the Jews at the ordination of a rabbi. Anointing with oil, which at first also accompanied the act of Baptism, and was analogous to the anointment of priests among the Jews, was not a necessary condition.

- "Ecumenical Council of Florence (1438–1445)" Archived 16 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine. The Circumcision Reference Library. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- Catechism of the Catholic Church: Article 5—The Fifth commandment Archived 29 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Christus Rex et Redemptor Mundi. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- Dietzen, John. "The Morality of Circumcision" Archived 10 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine, The Circumcision Reference Library. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- "Frequently Asked Questions: The Catholic Church and Circumcision". catholicdoors.com. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- "Should Catholics circumcise their sons? – Catholic Answers". Catholic.com. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- Arnold, Michelle. "The Catechism forbids deliberate mutilation, so why is non-therapeutic circumcision allowed?". Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- Slosar & O'Brien 2003, pp. 62–64.

- Eugenius IV 1990.

- "Circumcision". Columbia Encyclopedia. Columbia University Press. 2011. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- Adams & Adams 2012, pp. 291–298.

- Gruenbaum (2015), p. 61: "Christian theology generally interprets male circumcision to be an Old Testament rule that is no longer an obligation ... though in many countries (especially the United States and Sub-Saharan Africa, but not so much in Europe) it is widely practiced among Christians."; Peteet (2017), pp. 97–101: "male circumcision is still observed among Ethiopian and Coptic Christians, and circumcision rates are also high today in the Philippines and the US."; Ellwood (2008), p. 95: "It is obligatory among Jews, Muslims, and Coptic Christians. Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant Christians do not require circumcision. Starting in the last half of the 19th century, however, circumcision also became common among Christians in Europe and especially in North America."

- "Circumcision protest brought to Florence". Associated Press. 30 March 2008. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

However, the practice is still common among Christians in the United States, Oceania, South Korea, the Philippines, the Middle East and Africa. Some Middle Eastern Christians actually view the procedure as a rite of passage.

- Ray, Mary G. "82% of the World's Men are Intact", Mothers Against Circumcision, 1997.

- Richters, J.; Smith, A. M.; de Visser, R. O.; Grulich, A. E.; Rissel, C. E. (August 2006). "Circumcision in Australia: prevalence and effects on sexual health". Int J STD AIDS. 17 (8): 547–54. doi:10.1258/095646206778145730. PMID 16925903. S2CID 24396989.

- Williams, B. G.; et al. (2006). "The potential impact of male circumcision on HIV in sub-Saharan Africa". PLOS Med. 3 (7): e262. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030262. PMC 1489185. PMID 16822094.

- "Questions and answers: NIAID-sponsored adult male circumcision trials in Kenya and Uganda". National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. December 2006. Archived from the original on 9 March 2010.

- "Circumcision amongst the Dogon". The Non-European Components of European Patrimony (NECEP) Database. 2006. Archived from the original on 16 January 2006. Retrieved 3 September 2006.

- Pitts-Taylor 2008, p. 394, "For most part, Christianity does not require circumcision of its followers. Yet, some Orthodox and African Christian groups do require circumcision. These circumcisions take place at any point between birth and puberty.".

- Van Doorn-Harder, Nelly (2006). "Christianity: Coptic Christianity". Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices. 1. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015.

- Australia, Muslim Information Service of. "Male Circumcision in Islam". Archived from the original on 29 November 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- Ubayd 2006, p. 150.

- Jacobs 1998, p. 147.

- Silver 2022, p. 97.

- Betts 2013, p. 56.

- Hassall 2022, pp. 591–602.

- "Halal & Healthy: Is Kosher Halal" Archived 23 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine, SoundVision.com—Islamic information & products. 5 August 2009.

- Schuchmann, Jennifer (January–February 2006). "Does God Care What We Eat?". Today's Christian. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- Canon 1250, 1983. The 1983 Code of Canon Law specifies the obligations of Latin Church Catholic.

- "Fasting and Abstinence" Archived 1 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Catholic Online. 6 August 2009.

- Leviticus 11:1–47

- "Fundamental Beliefs" Archived 10 March 2006 at the Wayback Machine, No. 22. Christian Behavior. Seventh-Day Adventist Church website. 6 August 2009.

- Acts 15:19–21

- Schaff, Philip. "Canon II of The Council of Gangra". The Seven Ecumenical Councils. 6 August 2009. Commentary on Canon II of Gangra Archived 20 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Doctrine and Covenants 89". Church of Jesus Christ. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- Encyclopedia Talmudit (Hebrew edition, Israel, 5741/1981, entry Ben Noah, introduction) states that after the giving of the Torah, the Jewish people were no longer in the category of the sons of Noah; however, Maimonides (Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot M'lakhim 9:1) indicates that the seven laws are also part of the Torah, and the Talmud (Bavli, Sanhedrin 59a, see also Tosafot ad. loc.) states that Jews are obligated in all things that Gentiles are obligated in, albeit with some differences in the details.

- Barraclough, Geoffrey, ed. (1981) [1978]. Spectrum–Times Atlas van de Wereldgeschiedenis [The Times Atlas of World History] (in Dutch). Het Spectrum. pp. 102–103.

- Kornbluth 2003.

- Pope Paul VI. "Declaration on Religious Freedom" Archived 11 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine, 7 December 1965.

- Pullella, Philip (10 December 2015). "Vatican says Catholics should not try to convert Jews, should fight anti-semitism". Reuters. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- Hackett, Conrad; Mcclendon, David (2015). "Christians remain world's largest religious group, but they are declining in Europe". Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- "Religious Composition by Country, 2010–2050". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 2 April 2015. Archived from the original on 4 April 2015. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- "The Future of Global Muslim Population: Projections from 2010 to 2013" Archived 9 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine Accessed July 2013.

- Smith 2022b.

- "Baha'is by Country". World Religion Database. Institute on Culture, Religion, and World Affairs. 2020. Archived from the original on 9 December 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2020.(subscription required)

- Johnson & Grim 2013, pp. 59–62.

- Held 2008, p. 109, "Worldwide, they number 1 million or so, with about 45 to 50 percent in Syria, 35 to 40 percent in Lebanon, and less than 10 percent in Israel. Recently there has been a growing Druze diaspora.".

- Swayd 2015, p. 3, "The Druze world population at present is perhaps nearing two million; ...".

- "The Mandaeans – Who are the Mandaeans?". The Worlds of Mandaean Priests. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- Lev 2010.

- The Samaritan Update Archived 14 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 28 October 2021 "Total [sic] in 2021 – 840 souls Total in 2018 – 810 souls Total number on 1.1.2017 – 796 persons, 381 souls on Mount Gerizim and 415 in the State of Israel, of the 414 males and 382 females."

Works cited

- Able, John (2011). Apocalypse Secrets: Baha'i Interpretation of the Book of Revelation. John Able Books Limited. ISBN 978-0-9702847-7-8. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- Adams, C.J. (14 December 2007). "Classification of religions: Geographical". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 14 December 2007. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- Adams, Gregory; Adams, Kristina (2012). "Circumcision in the Early Christian Church: The Controversy That Shaped a Continent". In Bolnick, David A.; Koyle, Martin; Yosha, Assaf (eds.). Surgical Guide to Circumcision. London: Springer. pp. 291–298. doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-2858-8_26. ISBN 978-1-4471-2857-1. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- al-Misri, Ahmad ibn Naqib (1994). Reliance of the Traveler (edited and translated by Nuh Ha Mim Keller). Amana Publications. ISBN 978-0-915957-72-9.

- Baker, Mona; Saldanha, Gabriela (2008). Routledge encyclopedia of translation studies. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-36930-5. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- Beit-Hallahmi, Benjamin (28 December 1992). Rosen, Roger (ed.). The illustrated encyclopedia of active new religions, sects, and cults (1st ed.). New York: Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8239-1505-7.

- Benjamin, Don C. (1983). Deuteronomy and City Life: A Form Criticism of Texts with the Word City ('îr) in Deuteronomy 4:41–26:19. Reference, Information and Interdisciplinary Subjects Series. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America. ISBN 9780819131393. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- Berger, Alan L., ed. (2 November 2012). Trialogue and Terror: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam after 9/11. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-60899-546-2. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- Bertman, Stephen (2005). Handbook to life in ancient Mesopotamia (Paperback ed.). Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195183641.

- Betts, Robert Brenton (2013). The Sunni-Shi'a Divide: Islam's Internal Divisions and Their Global Consequences. Potomac Books, Inc. ISBN 9781612345239.

- Blasi, Anthony J.; Turcotte, Paul-André; Duhaime, Jean (2002). Handbook of early Christianity: social science approaches. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 978-0-7591-0015-2. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- Blumberg, Arnold (1985). Zion Before Zionism: 1838–1880. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-2336-6.

- Bremer, Thomas S. (2015). "Abrahamic religions". Formed From This Soil: An Introduction to the Diverse History of Religion in America. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-8927-9. LCCN 2014030507. S2CID 127980793. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- Browne, Edward Granville (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 03 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Buckley, Jorunn J. (2002). The Mandaeans: Ancient Texts and Modern People. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Carraway, George (2013). Christ is God Over All: Romans 9:5 in the context of Romans 9-11. The Library of New Testament Studies. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-567-26701-6. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

Second, it was probably not until the exile that monotheism proper was clearly formulated.

- Christiano, Kevin J.; Kivisto, Peter; Swatos, William H. Jr., eds. (2015) [2002]. "Excursus on the History of Religions". Sociology of Religion: Contemporary Developments (3rd ed.). Walnut Creek, California: AltaMira Press. pp. 254–255. doi:10.2307/3512222. ISBN 978-1-4422-1691-4. JSTOR 3512222. LCCN 2001035412. S2CID 154932078. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- Chryssides, George D. (2001) [1999]. "Independent New Religions: Rastafarianism". Exploring New Religions. Issues in Contemporary Religion. London and New York: Continuum International. doi:10.2307/3712544. ISBN 9780826459596. JSTOR 3712544. OCLC 436090427. S2CID 143265918. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- Cole, Juan (30 December 2012) [15 December 1988]. "BAHAISM i. The Faith". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. III/4. New York: Columbia University. ISSN 2330-4804. Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- Collins, William P. (1 September 2004). "Review of: The Children of Abraham : Judaism, Christianity, Islam / F. E. Peters. – New ed. – Princeton, NJ : Princeton University Press, 2004". Library Journal. 129 (14). Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- Corduan, Winfried (4 February 2013). Neighboring Faiths: A Christian Introduction to World Religions. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-7197-1. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- Daftary, Farhad (2 December 2013). A History of Shi'i Islam. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-0-85773-524-9.

- Dana, Léo-Paul (1 January 2010). Entrepreneurship and Religion. Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84980-632-9.

- Dana, Nissim (2003). The Druze in the Middle East: their faith, leadership, identity and status. Brighton [England]: Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 9781903900369.

- De Blois, F.C. (1960–2007). "Ṣābiʾ". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0952.

- Derrida, Jacques (2002). Anidjar, Gil (ed.). Acts of Religion. New York & London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-92401-6. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- Dever, William G. (2001). "Getting at the "History behind the History"". What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It?: What Archeology Can Tell Us About the Reality of Ancient Israel. Grand Rapids, Michigan and Cambridge, U.K.: Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2126-3. OCLC 46394298. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- Dodds, Adam (July 2009). "The Abrahamic Faiths? Continuity and Discontinuity in Christian and Islamic Doctrine". Evangelical Quarterly. 81 (3): 230–253. doi:10.1163/27725472-08103003.

- Drower, Ethel Stefana (1937). The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Dyrness, William A.; Kärkkäinen, Veli-Matti; Martinez, Juan F.; Chan, Simon (2008). Global Dictionary of Theology: A Resource for the Worldwide Church. Inter-Varsity Press. ISBN 978-1-84474-350-6. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- Ellwood, Robert S. (2008). The Encyclopedia of World Religions. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438110387.

- Edelman, Diana V. (1995). The Triumph of Elohim: From Yahwisms to Judaisms. Contributions to biblical exegesis and theology. Kok Pharos. ISBN 978-90-390-0124-0. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- Erickson, Millard J. (2001). Introducing Christian doctrine (2nd ed.). Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Academic. ISBN 0801022509.

- Esposito, John L (1999). The Oxford history of Islam. New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195107999.

- Eugenius IV (1990) [1442]. "Ecumenical Council of Florence (1438–1445): Session 11—4 February 1442; Bull of union with the Copts". In Norman P. Tanner (ed.). Decrees of the ecumenical councils. 2 volumes (in Greek and Latin). Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 978-0-87840-490-2. LCCN 90003209. Archived from the original on 25 April 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2007.

It denounces all who after that time observe circumcision.

- Fine, Steven (17 January 2011). The Temple of Jerusalem: From Moses to the Messiah: In Honor of Professor Louis H. Feldman. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-21471-2. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2002) [2001]. "9. The Transformation of Judah (c. 930-705 BCE)". The Bible Unearthed. Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and The Origin of Its Sacred Texts (First Touchstone Edition 2002 ed.). New York: Touchstone. ISBN 978-0-684-86913-1. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 1 September 2022.