Ammonium fluorosilicate

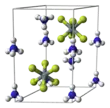

Ammonium fluorosilicate (also known as ammonium hexafluorosilicate, ammonium fluosilicate or ammonium silicofluoride) has the formula (NH4)2SiF6. It is a toxic chemical, like all salts of fluorosilicic acid.[4] It is made of white crystals,[5] which have at least three polymorphs[6] and appears in nature as rare minerals cryptohalite or bararite.

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Ammonium hexafluorosilicate | |||

| Other names

Ammonium fluorosilicate Ammonium fluosilicate | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.037.229 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

PubChem CID |

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 2854 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| (NH4)2[SiF6] | |||

| Appearance | White crystals | ||

| Density | 2.0 g cm−3 | ||

| Melting point | 100 °C (212 °F; 373 K) (decomposes)[1] | ||

| Solubility | dissolves in water and alcohol | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Other cations |

Hexafluorosilicic acid | ||

| Hazards[2][3] | |||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| |||

| Danger | |||

| H301, H311, H315, H319, H331, H335, H372 | |||

| P260, P261, P264, P270, P271, P280, P301+P310, P302+P352, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P312, P314, P321, P330, P332+P313, P337+P313, P362, P403+P233, P405, P501 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | ChemicalBook MSDS | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |||

Structure

Ammonium fluorosilicate has three major polymorphs: α-(NH4)2[SiF6] form is cubic (space group Fm3m, No. 225) and corresponds to the mineral cryptohalite. The β form is trigonal (scalenohedral) and occurs in nature as mineral bararite.[7] A third (γ) form was discovered in 2001 and identified with the hexagonal 6mm symmetry. In all three configurations, the [SiF6]2− octahedra are arranged in layers. In the α form, these layers are perpendicular to [111] directions. In the β- and γ- forms, the layers are perpendicular to the c-axis.[6] (Note: trigonal symmetry is part of the hexagonal group, but not all hexagonal crystals are trigonal.[8]) The silicon atoms of α-(NH4)2[SiF6] (alpha), have cubic close packing (CCP). The γ form has hexagonal close packing and the β-(NH4)2[SiF6] has primitive hexagonal packing.[9] In all three phases, 12 fluorine atoms neighbor the (NH4)+.[6]

Although bararite was claimed to be metastable at room temperature,[10] it does not appear one polymorph has ever turned into another.[6] Still, bararite is fragile enough that grinding it for spectroscopy will produce a little cryptohalite.[11] Even so, ammonium fluorosilicate assumes a trigonal form at pressures of 0.2 to 0.3 GPa. The reaction is irreversible. If it is not bararite, the phase is at least very closely related.[6]

The hydrogen bonding in (NH4)2[SiF6] allows this salt to change phases in ways that normal salts cannot. Interactions between cations and anions are especially important in how ammonium salts change phase.[6] (To learn more about the β-structure, see Bararite.)

Natural occurrence

This chemical makes rare appearances in nature.[12] It is found as a sublimation product of fumaroles and coal fires. As a mineral, it is either called cryptohalite or bararite, the two being two polymorphs of the compound.[7]

Chemical properties and health hazards

Ammonium fluorosilicate is noncombustible, but it will still release dangerous fumes in a fire, including hydrogen fluoride, silicon tetrafluoride, and nitrogen oxides. It will corrode aluminium. In water, ammonium fluorosilicate dissolves to form an acid solution.[5]

Inhaling dust can lead to pulmonary irritation, possibly death. Ingestion may also prove fatal. Irritation of the eyes comes from contact with the dust, as well as irritation or ulceration of the skin.[5]

Uses

Ammonium fluorosilicate finds use as a disinfectant, and it is useful in etching glass, metal casting, and electroplating.[5] It is also used to help neutralize washing machine water as laundry sour.

See also

References

- ammonium silicofluoride

- "Ammonium Hexafluorosilicate". PubChem. National Institute of Health. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

- "SAFETY DATA SHEET Ammonium hexafluorosilicate, 99.999%". Fisher Scientific. Archived from the original on 2017-10-16. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- Wiberg, E., Wiberg, N., and Holleman, A. F. (2001) Inorganic chemistry. Academic Press, San Diego.

- Ammonium fuorosilicate, CAMEO Chemicals, NOAA

- Boldyreva, E. V.; Shakhtshneider, T. P.; Sowa, H.; Ahsbas, H. (2007). "Effect of hydrostatic pressure up to 6 GPa on the crystal structures of ammonium and sodium hexafluorosilicates, (NH4)2[SiF6] and Na2[SiF6]; a phase transition in (NH4)2[SiF6] at 0.2–0.3 GPa". Zeitschrift für Kristallographie. 222: 23–29. doi:10.1524/zkri.2007.222.1.23. S2CID 97174719.

- Anthony, J. W., Bideaux, R. A., Bladh, K. W., and Nichols, M. C. (1997) Handbook of Mineralogy, Volume III: Halides, Hydroxides, Oxides. Mineral Data Publishing, Tucson.

- link to bararite Archived 2016-04-01 at the Wayback Machine

- link to cryptohalite Archived 2021-12-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Klein, C. and Dutrow, B. (2008) The 23rd Edition of the Manual of Mineral Science. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ.

- To learn about the primitive hexagonal structure, see Primitive hexagonal packing Archived 2009-05-26 at the Wayback Machine.

- Schlemper, Elmer O. (1966). "Structure of Cubic Ammonium Fluosilicate: Neutron-Diffraction and Neutron-Inelastic-Scattering Studies". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 44 (6): 2499–2505. doi:10.1063/1.1727071.

- Oxton, I. A., Knop, O., and Falk, M. (1975) "Infrared Spectra of the Ammonium Ion in Crystals". II. The Ammonium Ion in Trigonal Environments, with a Consideration of Hydrogen Bonding. Canadian Journal of Chemistry, 53, 3394–3400.

- Barnes, J. and Lapham, D. (1971) "Rare Minerals Found in Pennsylvania". Pennsylvania Geology, 2, 5, 6–8.