Dimethylmercury

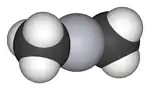

Dimethylmercury is an extremely toxic organomercury compound with the formula (CH3)2Hg. A volatile, flammable, dense and colorless liquid, dimethylmercury is one of the strongest known neurotoxins. Less than 0.1 mL is capable of inducing severe mercury poisoning resulting in death.[2]

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Dimethylmercury[1] | |

| Other names

Mercury dimethanide | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| 3600205 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.008.916 |

| EC Number |

|

| 25889 | |

| MeSH | dimethyl+mercury |

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 2929 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C 2H 6Hg (CH 3) 2Hg | |

| Molar mass | 230.66 g mol−1 |

| Appearance | Colorless liquid |

| Odor | Sweet |

| Density | 2.961 g mL−1 |

| Melting point | −43 °C (−45 °F; 230 K) |

| Boiling point | 93 to 94 °C (199 to 201 °F; 366 to 367 K) |

Refractive index (nD) |

1.543 |

| Thermochemistry | |

Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

57.9–65.7 kJ mol−1 |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards |

Extremely flammable, extremely poisonous, persistent environmental pollutant |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H224, H300+H310+H330, H372, H410 | |

| P260, P264, P273, P280, P284, P301+P310 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | 5 °C (41 °F; 278 K) |

| Related compounds | |

Related compounds |

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Synthesis, structure, and reactions

The compound was one of the earliest organometallics reported, reflecting its considerable stability. The compound was first prepared by George Buckton in 1857 by a reaction of methylmercury iodide with potassium cyanide:[3]

- 2 CH3HgI + 2 KCN → Hg(CH3)2 + 2 KI + (CN)2 + Hg

Later, Frankland discovered that it could be synthesized by treating sodium amalgam with methyl halides:

It can also be obtained by alkylation of mercuric chloride with methyllithium:

- HgCl2 + 2 LiCH3 → Hg(CH3)2 + 2 LiCl

The molecule adopts a linear structure with Hg–C bond lengths of 2.083 Å.[4]

Reactivity and physical properties

Dimethylmercury is stable in water and reacts with mineral acids at a significant rate only at elevated temperatures,[5][6] whereas the corresponding organocadmium and organozinc compounds (and most metal alkyls in general) hydrolyze rapidly. The difference reflects the high electronegativity of Hg (Pauling EN = 2.00) and the low affinity of Hg(II) for oxygen ligands. The compound undergoes a redistribution reaction with mercuric chloride to give methylmercury chloride:

- (CH3)2Hg + HgCl2 → 2 CH3HgCl

Whereas dimethylmercury is a volatile liquid, methylmercury chloride is a crystalline solid.[7]

Use

Dimethylmercury has few applications because of the risks involved. It has been studied for reactions involving bonding methylmercury cations to target molecules, forming potent bactericides, but methylmercury's bioaccumulation and ultimate toxicity has led it to be largely abandoned in favor of the less toxic ethylmercury and diethylmercury compounds, which perform a similar function without the bioaccumulation hazard.

In toxicology, it still finds limited use as a reference toxin. It is also used to calibrate NMR instruments for detection of mercury (δ 0 ppm for 199Hg NMR), although diethylmercury and less toxic mercury salts are now preferred.[8][9][10]

Safety

Dimethylmercury is extremely toxic and dangerous to handle. Absorption of doses as low as 0.1 mL can result in severe mercury poisoning.[2] The risks are enhanced because of the compound's high vapor pressure.[2] It is easily absorbed through the skin and permeating many materials, including plastic and rubber compounds.

Permeation tests showed that several types of disposable latex or polyvinyl chloride gloves (typically, about 0.1 mm thick), commonly used in most laboratories and clinical settings, had high and maximal rates of permeation by dimethylmercury within 15 seconds.[11] The American Occupational Safety and Health Administration advises handling dimethylmercury with highly resistant laminated gloves with an additional pair of abrasion-resistant gloves worn over the laminate pair, and also recommends using a face shield and working in a fume hood.[2][12]

Dimethylmercury is metabolized after several days to methylmercury.[11] Methylmercury crosses the blood–brain barrier easily, probably owing to formation of a complex with cysteine.[12] It is not quickly eliminated from the organism, and therefore has a tendency to bioaccumulate. The symptoms of poisoning may be delayed by months, resulting in cases in which a diagnosis is ultimately discovered, but only at a point in which it is too late or almost too late for an effective treatment regimen to be successful.[12] Methylmercury poisoning is also known as Minamata disease.

Incidents

As early as 1865, two workers in the laboratory of Edward Frankland died after exhibiting progressive neurological symptoms following accidental exposure to the compound.[3]

Karen Wetterhahn, a professor of chemistry at Dartmouth College, died in 1997, ten months after spilling only a few drops of dimethylmercury onto her latex gloves.[2][13] This incident resulted in improved safety procedures for chemical-protection clothing and fume hood use.[14]

Christoph Bulwin, a 40-year-old German database administrator for IG Bergbau, Chemie, Energie, was reportedly attacked with a syringe-tipped umbrella on 15 July 2011 in Hanover, Germany. Bulwin, who died a year later, claimed to have confiscated the syringe, which was later found to contain dimethylmercury;[15] leading to his death from mercury poisoning.[16][17][18] Police investigations, however, revealed a syringe containing a typical mercury thallium compound in Bulwin's car and mercury and thallium in thermometers at his workplace. Inconclusive antemortem and postmortem blood, urine, and tissue analysis cast doubts on the assault account. Alongside, the absence of an identified assailant or motive, and the presence of different mercury compounds in Bulwin's car led police to conclude that the intoxication was likely self-administered, thereby terminating the preliminary investigation.[19]

References

- "dimethylmercury – Compound Summary". PubChem Compound. US: National Center for Biotechnology Information. 16 September 2004. Identification and Related Records. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- "OSHA Hazard Information Bulletins – Dimethylmercury". OSHA.gov. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- The Chemistry of mercury. C. A. McAuliffe. London: Macmillan. 1977. ISBN 978-1-349-02489-6. OCLC 1057702183.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, Egon; Wiberg, Nils (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-352651-5.

- Crabtree, Robert H. (2005). The Organometallic Chemistry of the Transition Metals (4th ed.). Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley. p. 424. ISBN 0471662569. OCLC 61520528.

- Baughman, George L.; Gordon, John A.; Wolfe, N. Lee; Zepp, Richard G. (September 1973). Chemistry of Organomercurials in Aquatic Systems. United States Environmental Protection Agency Ecological Research Series. U.S. Govt. Print. Off. pp. 34–40. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- "Methylmercury chloride". PubChem. National Center for Biotechnology Information, United States National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- O'Halloran, T. V.; Singer, C. P. (10 March 1998). "199Hg Standards". Northwestern University. Archived from the original on 14 May 2005. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- Hoffman, R. (1 August 2011). "(Hg) Mercury NMR". Jerusalem: The Hebrew University. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- "Delayed Toxic Syndromes" (PDF). Terrorism by Fear and Uncertainty. ORAU. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 April 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- Nierenberg, David W.; Nordgren, Richard E.; Chang, Morris B.; Siegler, Richard W.; Blayney, Michael B.; Hochberg, Fred; Toribara, Taft Y.; Cernichiari, Elsa; Clarkson, Thomas (1998). "Delayed Cerebellar Disease and Death after Accidental Exposure to Dimethylmercury". New England Journal of Medicine. 338 (23): 1672–1676. doi:10.1056/NEJM199806043382305. PMID 9614258.

- Cotton, Simon (October 2003). "Dimethylmercury and Mercury Poisoning: The Karen Wetterhahn story". Molecule of the Month. Bristol University School of Chemistry. doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.5245807. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- "DimethylMercury and Mercury poisoning". Molecule of the Month www.chm.bris.ac.uk. October 2003. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- Cavanaugh, Ray (19 February 2019). "The dangers of dimethylmercury". Chemistry World. Royal Society of Chemistry. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- "Namen genannt! Wird der Regenschirm-Mord an Familienvater Christoph (†40) endlich gelöst?". TAG24 (in German). 25 August 2022. Archived from the original on 25 August 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- Albers, Anne; Gies, Ursula; Raatschen, Hans-Jurgen; Klintschar, Michael (1 September 2020). "Another umbrella murder? – A rare case of Minamata disease". Forensic Science, Medicine and Pathology. 16 (3): 504–509. doi:10.1007/s12024-020-00247-y. ISSN 1556-2891. PMC 7449996. PMID 32323188.

- "Umbrella stab victim dies of mercury poisoning". www.thelocal.de. 11 May 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- "Quecksilbervergiftung" [Mercury poisoning]. Der Spiegel (in German). 11 May 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- Albers, Anne; Gies, Ursula; Raatschen, Hans-Jurgen; Klintschar, Michael (1 September 2020). "Another umbrella murder? – A rare case of Minamata disease". Forensic Science, Medicine and Pathology. 16 (3): 504–509. doi:10.1007/s12024-020-00247-y. ISSN 1556-2891. PMC 7449996. PMID 32323188.