Heroin

Heroin, also known as diacetylmorphine and diamorphine among other names,[1] is a morphinan opioid substance synthesized from the dried latex of the Papaver somniferum plant and is mainly used as a recreational drug for its euphoric effects. Medical-grade diamorphine is used as a pure hydrochloride salt. Various white and brown powders sold illegally around the world as heroin are routinely diluted with cutting agents. Black tar heroin is a variable admixture of morphine derivatives—predominantly 6-MAM (6-monoacetylmorphine), which is the result of crude acetylation during clandestine production of street heroin.[3] Heroin is used medically in several countries to relieve pain, such as during childbirth or a heart attack, as well as in opioid replacement therapy.[8][9][10]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | Heroin: /ˈhɛroʊɪn/ |

| Other names | Diacetylmorphine, acetomorphine, (dual) acetylated morphine, morphine diacetate, Diamorphine[1] (BAN UK) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | heroin |

| Dependence liability | Very high[2] |

| Addiction liability | Very high[3] |

| Routes of administration | Intravenous, inhalation, transmucosal, by mouth, intranasal, rectal, intramuscular, subcutaneous, intrathecal |

| Drug class | Opioid |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | <35% (by mouth), 44–61% (inhaled)[4] |

| Protein binding | 0% (morphine metabolite 35%) |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Onset of action | Within minutes[5] |

| Elimination half-life | 2–3 minutes[6] |

| Duration of action | 4 to 5 hours[7] |

| Excretion | 90% kidney as glucuronides, rest biliary |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII |

|

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.008.380 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

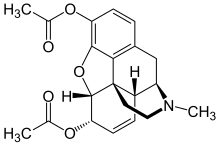

| Formula | C21H23NO5 |

| Molar mass | 369.417 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

It is typically injected, usually into a vein, but it can also be snorted, smoked, or inhaled. In a clinical context, the route of administration is most commonly intravenous injection; it may also be given by intramuscular or subcutaneous injection, as well as orally in the form of tablets.[11][3][12][13] The onset of effects is usually rapid and lasts for a few hours.[3]

Common side effects include respiratory depression (decreased breathing), dry mouth, drowsiness, impaired mental function, constipation, and addiction.[12] Use by injection can also result in abscesses, infected heart valves, blood-borne infections, and pneumonia.[12] After a history of long-term use, opioid withdrawal symptoms can begin within hours of the last use.[12] When given by injection into a vein, heroin has two to three times the effect of a similar dose of morphine.[3] It typically appears in the form of a white or brown powder.[12]

Treatment of heroin addiction often includes behavioral therapy and medications.[12] Medications can include buprenorphine, methadone, or naltrexone.[12] A heroin overdose may be treated with naloxone.[12] An estimated 17 million people as of 2015 use opiates, of which heroin is the most common,[14][15] and opioid use resulted in 122,000 deaths.[16] The total number of heroin users worldwide as of 2015 is believed to have increased in Africa, the Americas, and Asia since 2000.[17] In the United States, approximately 1.6 percent of people have used heroin at some point.[12][18] When people die from overdosing on a drug, the drug is usually an opioid and often heroin.[14][19]

Heroin was first made by C. R. Alder Wright in 1874 from morphine, a natural product of the opium poppy.[20] Internationally, heroin is controlled under Schedules I and IV of the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs,[21] and it is generally illegal to make, possess, or sell without a license.[22] About 448 tons of heroin were made in 2016.[17] In 2015, Afghanistan produced about 66% of the world's opium.[14] Illegal heroin is often mixed with other substances such as sugar, starch, caffeine, quinine, or other opioids like fentanyl.[3][23]

Uses

Recreational

Bayer's original trade name of heroin is typically used in non-medical settings. It is used as a recreational drug for the euphoria it induces. Anthropologist Michael Agar once described heroin as "the perfect whatever drug."[24] Tolerance develops quickly, and increased doses are needed in order to achieve the same effects. Its popularity with recreational drug users, compared to morphine, reportedly stems from its perceived different effects.[25]

Short-term addiction studies by the same researchers demonstrated that tolerance developed at a similar rate to both heroin and morphine. When compared to the opioids hydromorphone, fentanyl, oxycodone, and pethidine (meperidine), former addicts showed a strong preference for heroin and morphine, suggesting that heroin and morphine are particularly susceptible to misuse and causing dependence. Morphine and heroin were also much more likely to produce euphoria and other "positive" subjective effects when compared to these other opioids.[26]

Medical uses

In the United States, heroin is not accepted as medically useful.[3]

Under the generic name diamorphine, heroin is prescribed as a strong pain medication in the United Kingdom, where it is administered via oral, subcutaneous, intramuscular, intrathecal, intranasal or intravenous routes. It may be prescribed for the treatment of acute pain, such as in severe physical trauma, myocardial infarction, post-surgical pain and chronic pain, including end-stage terminal illnesses. In other countries it is more common to use morphine or other strong opioids in these situations. In 2004, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence produced guidance on the management of caesarean section, which recommended the use of intrathecal or epidural diamorphine for post-operative pain relief. For women who have had intrathecal opioids, there should be a minimum hourly observation of respiratory rate, sedation and pain scores for at least 12 hours for diamorphine and 24 hours for morphine. Women should be offered diamorphine (0.3–0.4 mg intrathecally) for intra- and postoperative analgesia because it reduces the need for supplemental analgesia after a caesarean section. Epidural diamorphine (2.5–5 mg) is a suitable alternative.[27]

Diamorphine continues to be widely used in palliative care in the UK, where it is commonly given by the subcutaneous route, often via a syringe driver if patients cannot easily swallow morphine solution. The advantage of diamorphine over morphine is that diamorphine is more fat soluble and therefore more potent by injection, so smaller doses of it are needed for the same effect on pain. Both of these factors are advantageous if giving high doses of opioids via the subcutaneous route, which is often necessary for palliative care.

It is also used in the palliative management of bone fractures and other trauma, especially in children. In the trauma context, it is primarily given by nose in hospital; although a prepared nasal spray is available.[28] It has traditionally been made by the attending physician, generally from the same "dry" ampoules as used for injection. In children, Ayendi nasal spray is available at 720 micrograms and 1600 micrograms per 50 microlitres actuation of the spray, which may be preferable as a non-invasive alternative in pediatric care, avoiding the fear of injection in children.[29]

Maintenance therapy

A number of European countries prescribe heroin for treatment of heroin addiction.[30] The initial Swiss HAT (heroin-assisted treatment) trial ("PROVE" study) was conducted as a prospective cohort study with some 1,000 participants in 18 treatment centers between 1994 and 1996, at the end of 2004, 1,200 patients were enrolled in HAT in 23 treatment centers across Switzerland.[31][32] Diamorphine may be used as a maintenance drug to assist the treatment of opiate addiction, normally in long-term chronic intravenous (IV) heroin users. It is only prescribed following exhaustive efforts at treatment via other means. It is sometimes thought that heroin users can walk into a clinic and walk out with a prescription, but the process takes many weeks before a prescription for diamorphine is issued. Though this is somewhat controversial among proponents of a zero-tolerance drug policy, it has proven superior to methadone in improving the social and health situations of addicts.[33]

The UK Department of Health's Rolleston Committee Report[34] in 1926 established the British approach to diamorphine prescription to users, which was maintained for the next 40 years: dealers were prosecuted, but doctors could prescribe diamorphine to users when withdrawing. In 1964, the Brain Committee recommended that only selected approved doctors working at approved specialized centres be allowed to prescribe diamorphine and cocaine to users. The law was made more restrictive in 1968. Beginning in the 1970s, the emphasis shifted to abstinence and the use of methadone; currently, only a small number of users in the UK are prescribed diamorphine.[35]

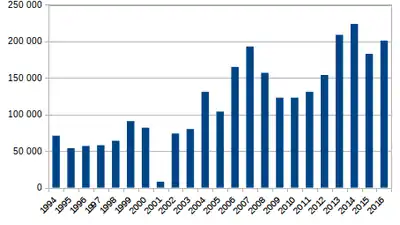

In 1994, Switzerland began a trial diamorphine maintenance program for users that had failed multiple withdrawal programs. The aim of this program was to maintain the health of the user by avoiding medical problems stemming from the illicit use of diamorphine. The first trial in 1994 involved 340 users, although enrollment was later expanded to 1000, based on the apparent success of the program. The trials proved diamorphine maintenance to be superior to other forms of treatment in improving the social and health situation for this group of patients.[33] It has also been shown to save money, despite high treatment expenses, as it significantly reduces costs incurred by trials, incarceration, health interventions and delinquency.[36] Patients appear twice daily at a treatment center, where they inject their dose of diamorphine under the supervision of medical staff. They are required to contribute about 450 Swiss francs per month to the treatment costs.[37] A national referendum in November 2008 showed 68% of voters supported the plan,[38] introducing diamorphine prescription into federal law. The previous trials were based on time-limited executive ordinances. The success of the Swiss trials led German, Dutch,[39] and Canadian[40] cities to try out their own diamorphine prescription programs.[41] Some Australian cities (such as Sydney) have instituted legal diamorphine supervised injecting centers, in line with other wider harm minimization programs.

Since January 2009, Denmark has prescribed diamorphine to a few addicts who have tried methadone and buprenorphine without success.[42] Beginning in February 2010, addicts in Copenhagen and Odense became eligible to receive free diamorphine. Later in 2010, other cities including Århus and Esbjerg joined the scheme. It was estimated that around 230 addicts would be able to receive free diamorphine.[43]

However, Danish addicts would only be able to inject heroin according to the policy set by Danish National Board of Health.[44] Of the estimated 1500 drug users who did not benefit from the then-current oral substitution treatment, approximately 900 would not be in the target group for treatment with injectable diamorphine, either because of "massive multiple drug abuse of non-opioids" or "not wanting treatment with injectable diamorphine".[45]

In July 2009, the German Bundestag passed a law allowing diamorphine prescription as a standard treatment for addicts; a large-scale trial of diamorphine prescription had been authorized in the country in 2002.[46]

On 26 August 2016, Health Canada issued regulations amending prior regulations it had issued under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act; the "New Classes of Practitioners Regulations", the "Narcotic Control Regulations", and the "Food and Drug Regulations", to allow doctors to prescribe diamorphine to people who have a severe opioid addiction who have not responded to other treatments.[47][48] The prescription heroin can be accessed by doctors through Health Canada's Special Access Programme (SAP) for "emergency access to drugs for patients with serious or life-threatening conditions when conventional treatments have failed, are unsuitable, or are unavailable."[47]

Routes of administration

| Recreational uses:

Medicinal uses: |

| Contraindications: |

| Central nervous system:

Neurological: Psychological: Cardiovascular & Respiratory: Gastrointestinal:

Musculoskeletal: Skin:

Miscellaneous:

|

The onset of heroin's effects depends upon the route of administration. Smoking is the fastest route of drug administration, although intravenous injection results in a quicker rise in blood concentration.[49] These are followed by suppository (anal or vaginal insertion), insufflation (snorting), and ingestion (swallowing).

A 2002 study suggests that a fast onset of action increases the reinforcing effects of addictive drugs. Ingestion does not produce a rush as a forerunner to the high experienced with the use of heroin, which is most pronounced with intravenous use. While the onset of the rush induced by injection can occur in as little as a few seconds, the oral route of administration requires approximately half an hour before the high sets in. Thus, with both higher the dosage of heroin used and faster the route of administration used, the higher the potential risk for psychological dependence/addiction.[50]

Large doses of heroin can cause fatal respiratory depression, and the drug has been used for suicide or as a murder weapon. The serial killer Harold Shipman used diamorphine on his victims, and the subsequent Shipman Inquiry led to a tightening of the regulations surrounding the storage, prescribing and destruction of controlled drugs in the UK.

Because significant tolerance to respiratory depression develops quickly with continued use and is lost just as quickly during withdrawal, it is often difficult to determine whether a heroin lethal overdose was accidental, suicide or homicide. Examples include the overdose deaths of Sid Vicious, Janis Joplin, Tim Buckley, Hillel Slovak, Layne Staley, Bradley Nowell, Ted Binion, and River Phoenix.[51]

By mouth

Use of heroin by mouth is less common than other methods of administration, mainly because there is little to no "rush", and the effects are less potent.[52] Heroin is entirely converted to morphine by means of first-pass metabolism, resulting in deacetylation when ingested. Heroin's oral bioavailability is both dose-dependent (as is morphine's) and significantly higher than oral use of morphine itself, reaching up to 64.2% for high doses and 45.6% for low doses; opiate-naive users showed far less absorption of the drug at low doses, having bioavailabilities of only up to 22.9%. The maximum plasma concentration of morphine following oral administration of heroin was around twice as much as that of oral morphine.[53]

Injection

Injection, also known as "slamming", "banging", "shooting up", "digging" or "mainlining", is a popular method which carries relatively greater risks than other methods of administration. Heroin base (commonly found in Europe), when prepared for injection, will only dissolve in water when mixed with an acid (most commonly citric acid powder or lemon juice) and heated. Heroin in the east-coast United States is most commonly found in the hydrochloride salt form, requiring just water (and no heat) to dissolve. Users tend to initially inject in the easily accessible arm veins, but as these veins collapse over time, users resort to more dangerous areas of the body, such as the femoral vein in the groin. Some medical professionals have expressed concern over this route of administration, as they suspect that it can lead to deep vein thrombosis.[54]

Intravenous users can use a variable single dose range using a hypodermic needle. The dose of heroin used for recreational purposes is dependent on the frequency and level of use.

As with the injection of any drug, if a group of users share a common needle without sterilization procedures, blood-borne diseases, such as HIV/AIDS or hepatitis, can be transmitted. The use of a common dispenser for water for the use in the preparation of the injection, as well as the sharing of spoons and filters can also cause the spread of blood-borne diseases. Many countries now supply small sterile spoons and filters for single use in order to prevent the spread of disease.[55]

Smoking

Smoking heroin refers to vaporizing it to inhale the resulting fumes, rather than burning and inhaling the smoke. It is commonly smoked in glass pipes made from glassblown Pyrex tubes and light bulbs. Heroin may be smoked from aluminium foil that is heated by a flame underneath it, with the resulting smoke inhaled through a tube of rolled up foil, a method also known as "chasing the dragon".[56]

Insufflation

Another popular route to intake heroin is insufflation (snorting), where a user crushes the heroin into a fine powder and then gently inhales it (sometimes with a straw or a rolled-up banknote, as with cocaine) into the nose, where heroin is absorbed through the soft tissue in the mucous membrane of the sinus cavity and straight into the bloodstream. This method of administration redirects first-pass metabolism, with a quicker onset and higher bioavailability than oral administration, though the duration of action is shortened. This method is sometimes preferred by users who do not want to prepare and administer heroin for injection or smoking but still experience a fast onset. Snorting heroin becomes an often unwanted route, once a user begins to inject the drug. The user may still get high on the drug from snorting, and experience a nod, but will not get a rush. A "rush" is caused by a large amount of heroin entering the body at once. When the drug is taken in through the nose, the user does not get the rush because the drug is absorbed slowly rather than instantly.

Heroin for pain has been mixed with sterile water on site by the attending physician, and administered using a syringe with a nebulizer tip.[57] Heroin may be used for fractures, burns, finger-tip injuries, suturing, and wound re-dressing, but is inappropriate in head injuries.[57]

Suppository

Little research has been focused on the suppository (anal insertion) or pessary (vaginal insertion) methods of administration, also known as "plugging". These methods of administration are commonly carried out using an oral syringe. Heroin can be dissolved and withdrawn into an oral syringe which may then be lubricated and inserted into the anus or vagina before the plunger is pushed. The rectum or the vaginal canal is where the majority of the drug would likely be taken up, through the membranes lining their walls.

Adverse effects

Heroin is classified as a hard drug in terms of drug harmfulness. Like most opioids, unadulterated heroin may lead to adverse effects. The purity of street heroin varies greatly, leading to overdoses when the purity is higher than expected.[59]

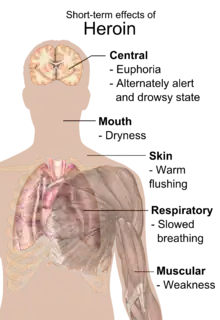

Short-term effects

Users report an intense rush, an acute transcendent state of euphoria, which occurs while diamorphine is being metabolized into 6-monoacetylmorphine (6-MAM) and morphine in the brain. Some believe that heroin produces more euphoria than other opioids; one possible explanation is the presence of 6-monoacetylmorphine, a metabolite unique to heroin – although a more likely explanation is the rapidity of onset. While other opioids of recreational use produce only morphine, heroin also leaves 6-MAM, also a psycho-active metabolite.

However, this perception is not supported by the results of clinical studies comparing the physiological and subjective effects of injected heroin and morphine in individuals formerly addicted to opioids; these subjects showed no preference for one drug over the other. Equipotent injected doses had comparable action courses, with no difference in subjects' self-rated feelings of euphoria, ambition, nervousness, relaxation, drowsiness, or sleepiness.[26]

The rush is usually accompanied by a warm flushing of the skin, dry mouth, and a heavy feeling in the extremities. Nausea, vomiting, and severe itching may also occur. After the initial effects, users usually will be drowsy for several hours; mental function is clouded; heart function slows, and breathing is also severely slowed, sometimes enough to be life-threatening. Slowed breathing can also lead to coma and permanent brain damage.[61] Heroin use has also been associated with myocardial infarction.[62]

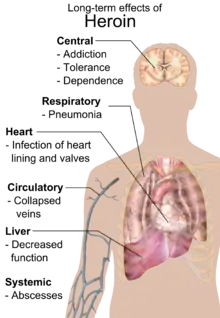

Long-term effects

Repeated heroin use changes the physical structure and physiology of the brain, creating long-term imbalances in neuronal and hormonal systems that are not easily reversed. Studies have shown some deterioration of the brain's white matter due to heroin use,[63] which may affect decision-making abilities, the ability to regulate behavior, and responses to stressful situations. Heroin also produces profound degrees of tolerance and physical dependence. Tolerance occurs when more and more of the drug is required to achieve the same effects. With physical dependence, the body adapts to the presence of the drug, and withdrawal symptoms occur if use is reduced abruptly.[61]

Injection

Intravenous use of heroin (and any other substance) with needles and syringes or other related equipment may lead to:

- Contracting blood-borne pathogens such as HIV and hepatitis via the sharing of needles

- Contracting bacterial or fungal endocarditis and possibly venous sclerosis

- Abscesses

- Poisoning from contaminants added to "cut" or dilute heroin

- Decreased kidney function (nephropathy), although it is not currently known if this is because of adulterants or infectious diseases[64]

Withdrawal

The withdrawal syndrome from heroin may begin within as little as two hours of discontinuation of the drug; however, this time frame can fluctuate with the degree of tolerance as well as the amount of the last consumed dose, and more typically begins within 6–24 hours after cessation. Symptoms may include sweating, malaise, anxiety, depression, akathisia, priapism, extra sensitivity of the genitals in females, general feeling of heaviness, excessive yawning or sneezing, rhinorrhea, insomnia, cold sweats, chills, severe muscle and bone aches, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, cramps, watery eyes,[65] fever, cramp-like pains, and involuntary spasms in the limbs (thought to be an origin of the term "kicking the habit"[66]).[67][68]

Overdose

Heroin overdose is usually treated with the opioid antagonist naloxone. This reverses the effects of heroin and causes an immediate return of consciousness but may result in withdrawal symptoms. The half-life of naloxone is shorter than some opioids, such that it may need to be given multiple times until the opioid has been metabolized by the body.

Between 2012 and 2015, heroin was the leading cause of drug-related deaths in the United States.[69] Since then, fentanyl has been a more common cause of drug-related deaths.[69]

Depending on drug interactions and numerous other factors, death from overdose can take anywhere from several minutes to several hours. Death usually occurs due to lack of oxygen resulting from the lack of breathing caused by the opioid. Heroin overdoses can occur because of an unexpected increase in the dose or purity or because of diminished opioid tolerance. However, many fatalities reported as overdoses are probably caused by interactions with other depressant drugs such as alcohol or benzodiazepines.[70] Since heroin can cause nausea and vomiting, a significant number of deaths attributed to heroin overdose are caused by aspiration of vomit by an unconscious person. Some sources quote the median lethal dose (for an average 75 kg opiate-naive individual) as being between 75 and 600 mg.[71][72] Illicit heroin is of widely varying and unpredictable purity. This means that the user may prepare what they consider to be a moderate dose while actually taking far more than intended. Also, tolerance typically decreases after a period of abstinence. If this occurs and the user takes a dose comparable to their previous use, the user may experience drug effects that are much greater than expected, potentially resulting in an overdose. It has been speculated that an unknown portion of heroin-related deaths are the result of an overdose or allergic reaction to quinine, which may sometimes be used as a cutting agent.[73]

Pharmacology

When taken orally, heroin undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism via deacetylation, making it a prodrug for the systemic delivery of morphine.[74] When the drug is injected, however, it avoids this first-pass effect, very rapidly crossing the blood–brain barrier because of the presence of the acetyl groups, which render it much more fat soluble than morphine itself.[75] Once in the brain, it then is deacetylated variously into the inactive 3-monoacetylmorphine and the active 6-monoacetylmorphine (6-MAM), and then to morphine, which bind to μ-opioid receptors, resulting in the drug's euphoric, analgesic (pain relief), and anxiolytic (anti-anxiety) effects; heroin itself exhibits relatively low affinity for the μ receptor.[76] Analgesia follows from the activation of the μ receptor G-protein coupled receptor, which indirectly hyperpolarizes the neuron, reducing the release of nociceptive neurotransmitters, and hence, causes analgesia and increased pain tolerance.[77]

Unlike hydromorphone and oxymorphone, however, administered intravenously, heroin creates a larger histamine release, similar to morphine, resulting in the feeling of a greater subjective "body high" to some, but also instances of pruritus (itching) when they first start using.[78][79]

Normally, GABA, which is released from inhibitory neurones, inhibits the release of dopamine. Opiates, like heroin and morphine, decrease the inhibitory activity of such neurones. This causes increased release of dopamine in the brain which is the reason for euphoric and rewarding effects of heroin.[80]

Both morphine and 6-MAM are μ-opioid agonists that bind to receptors present throughout the brain, spinal cord, and gut of all mammals. The μ-opioid receptor also binds endogenous opioid peptides such as β-endorphin, leu-enkephalin, and met-enkephalin. Repeated use of heroin results in a number of physiological changes, including an increase in the production of μ-opioid receptors (upregulation).[81] These physiological alterations lead to tolerance and dependence, so that stopping heroin use results in uncomfortable symptoms including pain, anxiety, muscle spasms, and insomnia called the opioid withdrawal syndrome. Depending on usage it has an onset 4–24 hours after the last dose of heroin. Morphine also binds to δ- and κ-opioid receptors.

There is also evidence that 6-MAM binds to a subtype of μ-opioid receptors that are also activated by the morphine metabolite morphine-6β-glucuronide but not morphine itself.[82] The third subtype of third opioid type is the mu-3 receptor, which may be a commonality to other six-position monoesters of morphine. The contribution of these receptors to the overall pharmacology of heroin remains unknown.

A subclass of morphine derivatives, namely the 3,6 esters of morphine, with similar effects and uses, includes the clinically used strong analgesics nicomorphine (Vilan), and dipropanoylmorphine; there is also the latter's dihydromorphine analogue, diacetyldihydromorphine (Paralaudin). Two other 3,6 diesters of morphine invented in 1874–75 along with diamorphine, dibenzoylmorphine and acetylpropionylmorphine, were made as substitutes after it was outlawed in 1925 and, therefore, sold as the first "designer drugs" until they were outlawed by the League of Nations in 1930.

Chemistry

Diamorphine is produced from acetylation of morphine derived from natural opium sources, generally using acetic anhydride.[83]

The major metabolites of diamorphine, 6-MAM, morphine, morphine-3-glucuronide, and morphine-6-glucuronide, may be quantitated in blood, plasma or urine to monitor for use, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning, or assist in a medicolegal death investigation. Most commercial opiate screening tests cross-react appreciably with these metabolites, as well as with other biotransformation products likely to be present following usage of street-grade diamorphine such as 6-Monoacetylcodeine and codeine.[84] However, chromatographic techniques can easily distinguish and measure each of these substances. When interpreting the results of a test, it is important to consider the diamorphine usage history of the individual, since a chronic user can develop tolerance to doses that would incapacitate an opiate-naive individual, and the chronic user often has high baseline values of these metabolites in his system. Furthermore, some testing procedures employ a hydrolysis step before quantitation that converts many of the metabolic products to morphine, yielding a result that may be 2 times larger than with a method that examines each product individually.[85]

History

The opium poppy was cultivated in lower Mesopotamia as long ago as 3400 BC.[86] The chemical analysis of opium in the 19th century revealed that most of its activity could be ascribed to the alkaloids codeine and morphine.

Diamorphine was first synthesized in 1874 by C. R. Alder Wright, an English chemist working at St. Mary's Hospital Medical School in London who had been experimenting combining morphine with various acids. He boiled anhydrous morphine alkaloid with acetic anhydride for several hours and produced a more potent, acetylated form of morphine which is now called diacetylmorphine or morphine diacetate. He sent the compound to F. M. Pierce of Owens College in Manchester for analysis. Pierce told Wright:

Doses… were subcutaneously injected into young dogs and rabbit… with the following general results… great prostration, fear, and sleepiness speedily following the administration, the eyes being sensitive, and pupils constrict, considerable salivation being produced in dogs, and a slight tendency to vomiting in some cases, but no actual emesis. Respiration was at first quickened, but subsequently reduced, and the heart's action was diminished and rendered irregular. Marked want of coordinating power over the muscular movements, and loss of power in the pelvis and hind limbs, together with a diminution of temperature in the rectum of about 4°.[87]

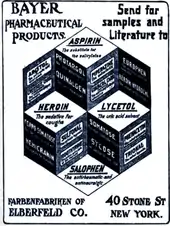

Wright's invention did not lead to any further developments, and diamorphine became popular only after it was independently re-synthesized 23 years later by chemist Felix Hoffmann.[88] Hoffmann was working at Bayer pharmaceutical company in Elberfeld, Germany, and his supervisor Heinrich Dreser instructed him to acetylate morphine with the objective of producing codeine, a constituent of the opium poppy that is pharmacologically similar to morphine but less potent and less addictive. Instead, the experiment produced an acetylated form of morphine one and a half to two times more potent than morphine itself. Hoffmann synthesized heroin on August 21, 1897, just eleven days after he had synthesized aspirin.[89]

The head of Bayer's research department reputedly coined the drug's new name of "heroin", based on the German heroisch which means "heroic, strong" (from the ancient Greek word "heros, ήρως"). Bayer scientists were not the first to make heroin, but their scientists discovered ways to make it, and Bayer led the commercialization of heroin.[90]

Bayer marketed diacetylmorphine as an over-the-counter drug under the trademark name Heroin.[91] It was developed chiefly as a morphine substitute for cough suppressants that did not have morphine's addictive side-effects. Morphine at the time was a popular recreational drug, and Bayer wished to find a similar but non-addictive substitute to market. However, contrary to Bayer's advertising as a "non-addictive morphine substitute", heroin would soon have one of the highest rates of addiction among its users.[92]

From 1898 through to 1910, diamorphine was marketed under the trademark name Heroin as a non-addictive morphine substitute and cough suppressant.[93] In the 11th edition of Encyclopædia Britannica (1910), the article on morphine states: "In the cough of phthisis minute doses [of morphine] are of service, but in this particular disease morphine is frequently better replaced by codeine or by heroin, which checks irritable coughs without the narcotism following upon the administration of morphine."

In the US, the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act was passed in 1914 to control the sale and distribution of diacetylmorphine and other opioids, which allowed the drug to be prescribed and sold for medical purposes. In 1924, the United States Congress banned its sale, importation, or manufacture. It is now a Schedule I substance, which makes it illegal for non-medical use in signatory nations of the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs treaty, including the United States.

The Health Committee of the League of Nations banned diacetylmorphine in 1925, although it took more than three years for this to be implemented. In the meantime, the first designer drugs, viz. 3,6 diesters and 6 monoesters of morphine and acetylated analogues of closely related drugs like hydromorphone and dihydromorphine, were produced in massive quantities to fill the worldwide demand for diacetylmorphine—this continued until 1930 when the Committee banned diacetylmorphine analogues with no therapeutic advantage over drugs already in use, the first major legislation of this type.

Bayer lost some of its trademark rights to heroin (as well as aspirin) under the 1919 Treaty of Versailles following the German defeat in World War I.[94][95]

Use of heroin by jazz musicians in particular was prevalent in the mid-twentieth century, including Billie Holiday, saxophonists Charlie Parker and Art Pepper, guitarist Joe Pass and piano player/singer Ray Charles; a "staggering number of jazz musicians were addicts".[96] It was also a problem with many rock musicians, particularly from the late 1960s through the 1990s. Pete Doherty is also a self-confessed user of heroin.[97] Nirvana lead singer Kurt Cobain's heroin addiction was well documented.[98] Pantera frontman Phil Anselmo turned to heroin while touring during the 1990s to cope with his back pain.[99] James Taylor, Jimmy Page, John Lennon, Eric Clapton, Johnny Winter, Keith Richards and Janis Joplin also used heroin. Many musicians have made songs referencing their heroin usage.[100][101][102][103][104]

Society and culture

Names

"Diamorphine" is the Recommended International Nonproprietary Name and British Approved Name.[105][106] Other synonyms for heroin include: diacetylmorphine, and morphine diacetate. Heroin is also known by many street names including dope, H, smack, junk, horse, scag, and brown, among others.[107]

Asia

In Hong Kong, diamorphine is regulated under Schedule 1 of Hong Kong's Chapter 134 Dangerous Drugs Ordinance. It is available by prescription. Anyone supplying diamorphine without a valid prescription can be fined $5,000,000 (HKD) and imprisoned for life. The penalty for trafficking or manufacturing diamorphine is a $5,000,000 (HKD) fine and life imprisonment. Possession of diamorphine without a license from the Department of Health is illegal with a $1,000,000 (HKD) fine and 7 years of jail time.[108][109]

Europe

In the Netherlands, diamorphine is a List I drug of the Opium Law. It is available for prescription under tight regulation exclusively to long-term addicts for whom methadone maintenance treatment has failed. It cannot be used to treat severe pain or other illnesses.[110]

In the United Kingdom, diamorphine is available by prescription, though it is a restricted Class A drug. According to the 50th edition of the British National Formulary (BNF), diamorphine hydrochloride may be used in the treatment of acute pain, myocardial infarction, acute pulmonary oedema, and chronic pain. The treatment of chronic non-malignant pain must be supervised by a specialist. The BNF notes that all opioid analgesics cause dependence and tolerance but that this is "no deterrent in the control of pain in terminal illness". When used in the palliative care of cancer patients, diamorphine is often injected using a syringe driver.[111]

In Switzerland, heroin is produced in injectable or tablet form under the name Diaphin by a private company under contract to the Swiss government.[112] Swiss-produced heroin has been imported into Canada with government approval.[113]

Australia

In Australia, diamorphine is listed as a schedule 9 prohibited substance under the Poisons Standard (October 2015).[114] A schedule 9 drug is outlined in the Poisons Act 1964 as "Substances which may be abused or misused, the manufacture, possession, sale or use of which should be prohibited by law except when required for medical or scientific research, or for analytical, teaching or training purposes with approval of the CEO."[115]

North America

In Canada, diamorphine is a controlled substance[116] under Schedule I of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA).[117] Any person seeking or obtaining diamorphine without disclosing authorization 30 days before obtaining another prescription from a practitioner is guilty of an indictable offense and subject to imprisonment for a term not exceeding seven years. Possession of diamorphine for the purpose of trafficking is an indictable offense and subject to imprisonment for life.

In the United States, diamorphine is a Schedule I drug according to the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, making it illegal to possess without a DEA license.[118] Possession of more than 100 grams of diamorphine or a mixture containing diamorphine is punishable with a minimum mandatory sentence of 5 years of imprisonment in a federal prison.

In 2021, the US state of Oregon became the first state to decriminalize the use of heroin after voters passed Ballot Measure 110 in 2020.[119] This measure will allow people with small amounts to avoid arrest.[120]

Turkey

Turkey maintains strict laws against the use, possession or trafficking of illegal drugs. If convicted under these offences, one could receive a heavy fine or a prison sentence of 4 to 24 years.[121]

Misuse of prescription medication

Misused prescription medicine, such as opioids, can lead to heroin use and dependence.[122] The number of death from illegal opioid overdose follows the increasing number of death caused by prescription opioid overdoses.[123] Prescription opioids are relatively easy to obtain.[124] This may ultimately lead to heroin injection because heroin is cheaper than prescribed pills.[122]

Production

Diamorphine is produced from acetylation of morphine derived from natural opium sources. One such method of heroin production involves isolation of the water-soluble components of raw opium, including morphine, in a strongly basic aqueous solution, followed by recrystallization of the morphine base by addition of ammonium chloride. The solid morphine base is then filtered out. The morphine base is then reacted with acetic anhydride, which forms heroin. This highly impure brown heroin base may then undergo further purification steps, which produces a white-colored product; the final products have a different appearance depending on purity and have different names.[83] Heroin purity has been classified into four grades. No.4 is the purest form – white powder (salt) to be easily dissolved and injected. No.3 is "brown sugar" for smoking (base). No.1 and No.2 are unprocessed raw heroin (salt or base).[125]

Trafficking

Traffic is heavy worldwide, with the biggest producer being Afghanistan. According to a U.N. sponsored survey,[126] in 2004, Afghanistan accounted for production of 87 percent of the world's diamorphine.[127] Afghan opium kills around 100,000 people annually.[128]

In 2003 The Independent reported:[129][130]

The cultivation of opium [in Afghanistan] reached its peak in 1999, when 350 square miles (910 km2) of poppies were sown ... The following year the Taliban banned poppy cultivation, ... a move which cut production by 94 percent ... By 2001 only 30 square miles (78 km2) of land were in use for growing opium poppies. A year later, after American and British troops had removed the Taliban and installed the interim government, the land under cultivation leapt back to 285 square miles (740 km2), with Afghanistan supplanting Burma to become the world's largest opium producer once more.

Opium production in that country has increased rapidly since, reaching an all-time high in 2006. War in Afghanistan once again appeared as a facilitator of the trade.[131] Some 3.3 million Afghans are involved in producing opium.[132]

At present, opium poppies are mostly grown in Afghanistan (224,000 hectares (550,000 acres)), and in Southeast Asia, especially in the region known as the Golden Triangle straddling Burma (57,600 hectares (142,000 acres)), Thailand, Vietnam, Laos (6,200 hectares (15,000 acres)) and Yunnan province in China. There is also cultivation of opium poppies in Pakistan (493 hectares (1,220 acres)), Mexico (12,000 hectares (30,000 acres)) and in Colombia (378 hectares (930 acres)).[133] According to the DEA, the majority of the heroin consumed in the United States comes from Mexico (50%) and Colombia (43–45%) via Mexican criminal cartels such as Sinaloa Cartel.[134] However, these statistics may be significantly unreliable, the DEA's 50/50 split between Colombia and Mexico is contradicted by the amount of hectares cultivated in each country and in 2014, the DEA claimed most of the heroin in the US came from Colombia.[135] As of 2015, the Sinaloa Cartel is the most active drug cartel involved in smuggling illicit drugs such as heroin into the United States and trafficking them throughout the United States.[136] According to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, 90% of the heroin seized in Canada (where the origin was known) came from Afghanistan.[137] Pakistan is the destination and transit point for 40 percent of the opiates produced in Afghanistan, other destinations of Afghan opiates are Russia, Europe and Iran.[138][139]

A conviction for trafficking heroin carries the death penalty in most Southeast Asian, some East Asian and Middle Eastern countries (see Use of death penalty worldwide for details), among which Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand are the strictest. The penalty applies even to citizens of countries where the penalty is not in place, sometimes causing controversy when foreign visitors are arrested for trafficking, for example, the arrest of nine Australians in Bali, the death sentence given to Nola Blake in Thailand in 1987, or the hanging of an Australian citizen Van Tuong Nguyen in Singapore.

Trafficking history

The origins of the present international illegal heroin trade can be traced back to laws passed in many countries in the early 1900s that closely regulated the production and sale of opium and its derivatives including heroin. At first, heroin flowed from countries where it was still legal into countries where it was no longer legal. By the mid-1920s, heroin production had been made illegal in many parts of the world. An illegal trade developed at that time between heroin labs in China (mostly in Shanghai and Tianjin) and other nations. The weakness of the government in China and conditions of civil war enabled heroin production to take root there. Chinese triad gangs eventually came to play a major role in the illicit heroin trade. The French Connection route started in the 1930s.

Heroin trafficking was virtually eliminated in the US during World War II because of temporary trade disruptions caused by the war. Japan's war with China had cut the normal distribution routes for heroin and the war had generally disrupted the movement of opium. After World War II, the Mafia took advantage of the weakness of the postwar Italian government and set up heroin labs in Sicily which was located along the historic route opium took westward into Europe and the United States.[140] Large-scale international heroin production effectively ended in China with the victory of the communists in the civil war in the late 1940s. The elimination of Chinese production happened at the same time that Sicily's role in the trade developed.

Although it remained legal in some countries until after World War II, health risks, addiction, and widespread recreational use led most western countries to declare heroin a controlled substance by the latter half of the 20th century. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the CIA supported anti-Communist Chinese Nationalists settled near the Sino-Burmese border and Hmong tribesmen in Laos. This helped the development of the Golden Triangle opium production region, which supplied about one-third of heroin consumed in the US after the 1973 American withdrawal from Vietnam. In 1999, Burma, the heartland of the Golden Triangle, was the second-largest producer of heroin, after Afghanistan.[141]

The Soviet-Afghan war led to increased production in the Pakistani-Afghan border regions, as US-backed mujaheddin militants raised money for arms from selling opium, contributing heavily to the modern Golden Crescent creation. By 1980, 60 percent of the heroin sold in the US originated in Afghanistan.[141] It increased international production of heroin at lower prices in the 1980s. The trade shifted away from Sicily in the late 1970s as various criminal organizations violently fought with each other over the trade. The fighting also led to a stepped-up government law enforcement presence in Sicily.

Following the discovery at a Jordanian airport of a toner cartridge that had been modified into an improvised explosive device, the resultant increased level of airfreight scrutiny led to a major shortage (drought) of heroin from October 2010 until April 2011. This was reported in most of mainland Europe and the UK which led to a price increase of approximately 30 percent in the cost of street heroin and increased demand for diverted methadone. The number of addicts seeking treatment also increased significantly during this period. Other heroin droughts (shortages) have been attributed to cartels restricting supply in order to force a price increase and also to a fungus that attacked the opium crop of 2009. Many people thought that the American government had introduced pathogens into the Afghanistan atmosphere in order to destroy the opium crop and thus starve insurgents of income.

On 13 March 2012, Haji Bagcho, with ties to the Taliban, was convicted by a US District Court of conspiracy, distribution of heroin for importation into the United States and narco-terrorism.[142][143][144][145][146] Based on heroin production statistics[147] compiled by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, in 2006, Bagcho's activities accounted for approximately 20 percent of the world's total production for that year.[143][144][145][146]

Street price

The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction reports that the retail price of brown heroin varies from €14.5 per gram in Turkey to €110 per gram in Sweden, with most European countries reporting typical prices of €35–40 per gram. The price of white heroin is reported only by a few European countries and ranged between €27 and €110 per gram.[148]

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime claims in its 2008 World Drug Report that typical US retail prices are US$172 per gram.[149]

Research

Researchers are attempting to reproduce the biosynthetic pathway that produces morphine in genetically engineered yeast.[150] In June 2015 the S-reticuline could be produced from sugar and R-reticuline could be converted to morphine, but the intermediate reaction could not be performed.[151]

See also

- Allegations of CIA drug trafficking – Claims

- Cheese (recreational drug) – Heroin-based recreational drug

- The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia – 1972 non-fiction book

References

- Sweetman SC, ed. (2009). Martindale: the complete drug reference (36th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-85369-840-1.

- Bonewit-West K, Hunt SA, Applegate E (2012). Today's Medical Assistant: Clinical and Administrative Procedures. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 571. ISBN 9781455701506.

- "Heroin". Drugs.com. 18 May 2014. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- Rook EJ, van Ree JM, van den Brink W, Hillebrand MJ, Huitema AD, Hendriks VM, Beijnen JH (January 2006). "Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of high doses of pharmaceutically prepared heroin, by intravenous or by inhalation route in opioid-dependent patients". Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 98 (1): 86–96. doi:10.1111/j.1742-7843.2006.pto_233.x. PMID 16433897.

- Riviello RJ (2010). Manual of forensic emergency medicine: a guide for clinicians. Sudbury, Mass.: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-7637-4462-5. Archived from the original on 18 March 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- "Diamorphine Hydrochloride Injection 30 mg – Summary of Product Characteristics". electronic Medicines Compendium. ViroPharma Limited. 24 September 2013. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- Field J (2012). The Textbook of Emergency Cardiovascular Care and CPR. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 447. ISBN 978-1-4698-0162-9. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- Friedrichsdorf SJ, Postier A (2014). "Management of breakthrough pain in children with cancer". Journal of Pain Research. 7: 117–23. doi:10.2147/JPR.S58862. PMC 3953108. PMID 24639603.

- National Collaborating Centre for Cancer (UK) (May 2012). Opioids in Palliative Care: Safe and Effective Prescribing of Strong Opioids for Pain in Palliative Care of Adults. Cardiff (UK): National Collaborating Centre for Cancer (UK). PMID 23285502.

- Uchtenhagen AA (March 2011). "Heroin maintenance treatment: from idea to research to practice" (PDF). Drug and Alcohol Review. 30 (2): 130–7. doi:10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00266.x. PMID 21375613. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- "Diamorphine". SPS – Specialist Pharmacy Service. 15 February 2013.

- "DrugFacts—Heroin". National Institute on Drug Abuse. October 2014. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- National Institutes on Drug Abuse (2014). Research Report Series: Heroin (PDF). National Institutes on Drug Abuse. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 December 2016.

Highly pure heroin can be snorted or smoked and may be more appealing to new users because it eliminates the stigma associated with injection drug use…. Impure heroin is usually dissolved, diluted, and injected into veins, muscles, or under the skin.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (May 2016). "Statistical tables" (PDF). World Drug Report 2016. Vienna, Austria. p. xii, 18, 32. ISBN 978-92-1-057862-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Information sheet on opioid overdose". WHO. August 2018. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, et al. (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- World Drug Report 2017 Part 3 (PDF). United Nations. May 2017. pp. 14, 24. ISBN 978-92-1-148294-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 July 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- "What is the scope of heroin use in the United States?". National Institute on Drug Abuse. Archived from the original on 10 December 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- Valencia M (23 June 2016). "Record 29 million people drug-dependent worldwide; heroin use up sharply – UN report". United Nations Sustainable Development. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- A Century of International Drug Control. United Nations Publications. 2010. p. 49. ISBN 9789211482454. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- "Yellow List: List of Narcotic Drugs Under International Control" (PDF). International Narcotics Control Board. December 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2006. Referring URL = "Yellow List". Archived from the original on 21 June 2006. Retrieved 21 June 2006.

- Lyman MD (2013). Drugs in Society: Causes, Concepts, and Control. Routledge. p. 45. ISBN 9780124071674. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- Cole C (2010). CUT: a guide to adulterants, bulking agents and other contaminants found in illicit drugs. Liverpool: Centre for Public Health. Faculty of Health and Applied Social Sciences, John Moores University. ISBN 978-1-907441-47-9. OCLC 650080999.

- Agar M. "Dope Double Agent: The Naked Emperor on Drugs". Archived from the original on 17 November 2009. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

What a great New York drug heroin was, I thought. As any city, but more than most, New York is an information overload, a constant perceptual tornado that surrounds you most places you walk on the streets. Heroin is the audio-visual technology that helps manage that overload by dampening it in general and allowing a focus on some part of it that the human perceptual equipment was, in fact, designed to handle.

- Tschacher W, Haemmig R, Jacobshagen N (January 2003). "Time series modeling of heroin and morphine drug action". Psychopharmacology. 165 (2): 188–93. doi:10.1007/s00213-002-1271-3. PMID 12404073. S2CID 33612363.

- Martin WR, Fraser HF (September 1961). "A comparative study of physiological and subjective effects of heroin and morphine administered intravenously in postaddicts". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 133: 388–99. PMID 13767429.

- "National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2011) Caesarean section.NICE Guideline (CG132)". 23 November 2011. Archived from the original on 25 October 2015. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- "Ayendi 720microgram/actuation Nasal Spray – Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) – (emc)". www.medicines.org.uk. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- "BNFc is only available in the UK". NICE. NICE – national institute for health and care excellence. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- Lintzeris N (2009). "Prescription of heroin for the management of heroin dependence: current status". CNS Drugs. 23 (6): 463–76. doi:10.2165/00023210-200923060-00002. PMID 19480466. S2CID 11018732.

- "Preliminary Pages". Prescriptions of Narcotics for Heroin Addicts. Medical Prescription of Narcotics. Vol. 1. 1999. doi:10.1159/000062984. ISBN 3-8055-6791-X.

- Fischer B, Oviedo-Joekes E, Blanken P, Haasen C, Rehm J, Schechter MT, et al. (July 2007). "Heroin-assisted treatment (HAT) a decade later: a brief update on science and politics". Journal of Urban Health. 84 (4): 552–62. doi:10.1007/s11524-007-9198-y. PMC 2219559. PMID 17562183.

- Haasen C, Verthein U, Degkwitz P, Berger J, Krausz M, Naber D (July 2007). "Heroin-assisted treatment for opioid dependence: randomised controlled trial". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 191: 55–62. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.026112. PMID 17602126.

- "Rolleston Report". Departmental Commission on Morphine and Heroin Addiction, United Kingdom. 1926. Archived from the original on 17 April 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- Goldacre B (1998). "Methadone and Heroin: An Exercise in Medical Scepticism". Archived from the original on 4 March 2007. Retrieved 18 December 2006.

- "Heroin Assisted Treatment for Opiate Addicts – The Swiss Experience". Parl.gc.ca. 31 March 1995. Archived from the original on 20 January 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- Nadelmann E (10 July 1995). "Switzerland's Heroin Experiment". Drug Policy Alliance. Archived from the original on 29 November 2004. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- "Swiss approve prescription heroin". BBC News Online. 30 November 2008. Archived from the original on 30 November 2008. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- "Heroin prescription 'cuts costs'". BBC News. 5 June 2005. Archived from the original on 28 June 2006. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- "About the study". North American Opiate Medication Initiative. Archived from the original on 4 November 2006. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- Nordt C, Stohler R (June 2006). "Incidence of heroin use in Zurich, Switzerland: a treatment case register analysis" (PDF). Lancet. 367 (9525): 1830–4. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.190.1876. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68804-1. PMID 16753485. S2CID 46366844. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2010.

- "Danmark redo för skattebetalt heroin" [Denmark ready for tax-paid heroin] (in Swedish). November 2008. Archived from the original on 3 December 2008. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- "Gratis heroin klar til danske narkomaner" [Free heroin ready for Danish drug addicts] (in Danish). Information. January 2010. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- Dahlin U (February 2009). "Heroin-behandling bliver kun i kanyler" [Heroin treatment stays only in needles] (in Danish). Information. Archived from the original on 20 February 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- Prescription of injectable heroin for drug users (Report). Danish National Boad of Health. October 2007. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- "Durchbruch für die Behandlung von Schwerstopiatabhängigen" [Breakthrough for the treatment of heavily addicted opiate users] (in German). Bundesministerium für Gesundheit (German ministry of health). 28 May 2009. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- "Regulations Amending Certain Regulations Made Under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (Access to Diacetylmorphine for Emergency Treatment)". Canada Gazette Directorate. 7 September 2016. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- "Prescription heroin gets green light in Canada". CNN. 14 September 2016. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- Budman SH, Grimes Serrano JM, Butler SF (May 2009). "Can abuse deterrent formulations make a difference? Expectation and speculation". Harm Reduction Journal. 6 (8): 8. doi:10.1186/1477-7517-6-8. PMC 2694768. PMID 19480676.

- Winger G, Hursh SR, Casey KL, Woods JH (May 2002). "Relative reinforcing strength of three N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonists with different onsets of action". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 301 (2): 690–7. doi:10.1124/jpet.301.2.690. PMID 11961074. S2CID 17860947.

- Eason K, Naughton P (13 March 2012). "First murder charge over heroin mix that killed 400". Times Online. London. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- sepulfreak (8 July 2005). "Erowid Experience Vaults: Heroin – Catching the Waves – 41495". Erowid.org. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- Halbsguth U, Rentsch KM, Eich-Höchli D, Diterich I, Fattinger K (December 2008). "Oral diacetylmorphine (heroin) yields greater morphine bioavailability than oral morphine: bioavailability related to dosage and prior opioid exposure". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 66 (6): 781–91. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03286.x. PMC 2675771. PMID 18945270.

- Strang J, Gossop M (2005). Heroin Addiction and the British System: Treatment and policy responses. Psychology Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-415-29817-9.

- Thakarar K, Nenninger K, Agmas W (September 2020). "Harm Reduction Services to Prevent and Treat Infectious Diseases in People Who Use Drugs". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 34 (3): 605–620. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2020.06.013. PMC 7596878. PMID 32782104.

- Strang J, Griffiths P, Gossop M (June 1997). "Heroin smoking by 'chasing the dragon': origins and history". Addiction. 92 (6): 673–83, discussion 685–95. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.1997.9266734.x. PMID 9246796.

- "Clinical Policy for the Use of Intranasal Diamorphine for Analgesia in Children Attending the Paediatric Emergency Department, SASH" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- Nutt DJ, King LA, Phillips LD (November 2010). "Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis". Lancet. 376 (9752): 1558–65. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.690.1283. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. PMID 21036393. S2CID 5667719.

- Seelye KQ (25 March 2016). "Heroin Epidemic Is Yielding to a Deadlier Cousin: Fentanyl". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 January 2022.

- "Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP): Heroin Facts & Figures". Whitehousedrugpolicy.gov. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. "What are the immediate (short-term) effects of heroin use?". Archived from the original on 8 September 2018. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- Karoli R, Fatima J, Singh P, Kazmi KI (July 2012). "Acute myocardial involvement after heroin inhalation". Journal of Pharmacology & Pharmacotherapeutics. 3 (3): 282–4. doi:10.4103/0976-500X.99448. PMC 3487283. PMID 23129970.

- Hampton WH, Hanik I, Olson IR (2019). "[Substance Abuse and White Matter: Findings, Limitations, and Future of Diffusion Tensor Imaging Research]". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 197 (4): 288–298. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.02.005. PMC 6440853. PMID 30875650.

- Dettmeyer RB, Preuss J, Wollersen H, Madea B (January 2005). "Heroin-associated nephropathy". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 4 (1): 19–28. doi:10.1517/14740338.4.1.19. PMID 15709895. S2CID 11646280.

- Myaddiction (16 May 2012). "Heroin Withdrawal Symptoms". MyAddiction. Archived from the original on 11 May 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- Stephens R (1991). The Street Addict Role: A Theory of Heroin Addiction. SUNY Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-7914-0619-9.

- "Narcotic Drug Withdrawal". Discovery Place. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- "Opiate and opioid withdrawal: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- "Drugs Most Frequently Involved in Drug Overdose Deaths: United States, 2011–2016" (PDF). CDC. 12 December 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2018. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- Darke S, Zador D (December 1996). "Fatal heroin 'overdose': a review". Addiction. 91 (12): 1765–72. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.911217652.x. PMID 8997759.

- "Toxic Substances in water". Lincoln.pps.k12.or.us. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- Breecher E. "The Consumers Union Report on Licit and Illicit Drugs". Archived from the original on 8 February 2007.

- Brecher EM, et al. (Editors of Consumer Reports Magazine) (1972). "Chapter 12. The "heroin overdose" mystery and other occupational hazards of addiction". The Consumers Union Report on Licit and Illicit Drugs. Schaffer Library of Drug Policy. Archived from the original on 8 February 2007.

- Sawynok J (January 1986). "The therapeutic use of heroin: a review of the pharmacological literature". Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 64 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1139/y86-001. PMID 2420426.

- Klous MG, Van den Brink W, Van Ree JM, Beijnen JH (December 2005). "Development of pharmaceutical heroin preparations for medical co-prescription to opioid dependent patients". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 80 (3): 283–95. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.04.008. PMID 15916865.

- Inturrisi CE, Schultz M, Shin S, Umans JG, Angel L, Simon EJ (1983). "Evidence from opiate binding studies that heroin acts through its metabolites". Life Sciences. 33 (Suppl 1): 773–6. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(83)90616-1. PMID 6319928.

- Hitchings A, Lonsdale D, Burrage D, Baker E (2014). Top 100 drugs: clinical pharmacology and practical prescribing. Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 9780702055164.

- "Histamine release by morphine and diamorphine in man". Archived from the original on 12 August 2010.

- Del Giudice P (January 2004). "Cutaneous complications of intravenous drug abuse". The British Journal of Dermatology. 150 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05607.x. PMID 14746612. S2CID 32380001. Archived from the original on 23 November 2012.

- Papich MG (2016). "Codeine". Saunders Handbook of Veterinary Drugs (Fourth ed.). W.B. Saunders. pp. 183–184. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-24485-5.00175-3. ISBN 9780323244855.

- Hammers A, Asselin MC, Hinz R, Kitchen I, Brooks DJ, Duncan JS, Koepp MJ (April 2007). "Upregulation of opioid receptor binding following spontaneous epileptic seizures". Brain. 130 (Pt 4): 1009–16. doi:10.1093/brain/awm012. PMID 17301080.

- Brown GP, Yang K, King MA, Rossi GC, Leventhal L, Chang A, Pasternak GW (July 1997). "3-Methoxynaltrexone, a selective heroin/morphine-6beta-glucuronide antagonist". FEBS Letters. 412 (1): 35–8. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00710-2. PMID 9257684. S2CID 45475657.

- "Documentation of a heroin manufacturing process in Afghanistan. BULLETIN ON NARCOTICS, Volume LVII, Nos. 1 and 2, 2005" (PDF). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 July 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- "Opiates - Mayo Clinic Laboratories". www.mayocliniclabs.com. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- Baselt R (2011). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (9th ed.). Seal Beach, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 793–7. ISBN 978-0-9626523-8-7.

- "Opium Throughout History". PBS Frontline. Archived from the original on 23 September 2006. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- Wright CR (12 August 2003). "On the action of organic acids and their anhydrides on the natural alkaloids". Archived from the original on 6 June 2004. Note: this is an annotated excerpt of Wright CR (1874). "On the action of organic acids and their anhydrides on the natural alkaloids". Journal of the Chemical Society. 27: 1031–1043. doi:10.1039/js8742701031.

- "Felix Hoffmann". Science History Institute. June 2016. Archived from the original on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Schaefer, Bernd (2015). Natural Products in the Chemical Industry. Springer. p. 316. ISBN 9783642544613. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- Edwards J (17 November 2011). "Yes, Bayer Promoted Heroin for Children – Here Are The Ads That Prove It". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 1 May 2015.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- "The Most Addictive Drugs". Archived from the original on 13 February 2010.

- Moore D (24 August 2014). "Heroin: A brief history of unintended consequences". Times Union. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015.

- Schlager N, Lauer J (2001). Science and Its Times: Understanding the Social Significance of Scientific Discovery. Detroit: Gale Group. pp. 360. ISBN 078763932X. OCLC 43836551.

- "Happy birthday to the wonder drug that changed our lives". The Guardian. 6 March 1999.

- Martin H, Waters K (25 January 2008). Essential Jazz: The First 100 Years. Cengage Learning. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-495-50525-9. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- Michaels S (28 June 2012). "Pete Doherty skips T in the Park to enter rehab". The Guardian.

- Azerrad M (1993). Come as You Are: The Story of Nirvana (1st ed.). New York: Doubleday. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-385-47199-2.

- "Philip Anselmo Opens Up About His Heroin Addiction, Pantera's Breakup". Blabbermouth.net. 19 August 2009. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- Sweeting A (9 July 2004). "I died. I do remember that". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016.

- Brown P (2002) [1983]. The Love You Make: An Insider's Story of The Beatles. New York: McGraw-Hill / New American Library. p. 331. ISBN 978-0-07-008159-8.

- Bates M (December 2008). "Loaded – Great heroin songs of the rock era" (PDF). pp. 26–27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2008. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- Liner notes, Music Bank box set. 1999.

- Howard G (18 September 2009). "Death of a Poet: Saying goodbye to Jim Carroll". Slate. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- Rang HP, Ritter JM, Flower RJ, Henderson G (2014). Rang & Dale's Pharmacology (8th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 515. ISBN 9780702054976. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

While 'diamorphine' is the recommended International Nonproprietary Name (rINN), this drug is widely known as heroin.

- Rang HP, Ritter JM, Flower RJ, Henderson G (2011). Rang & Dale's pharmacology (7th ed.). Edinburgh, UK: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-7020-3471-8.

- "Nicknames and Street Names for Heroin". Thecyn.com. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- "Heroin, the Poppy". Addiction Recovery Expose. Randolph Online Solutions Inc. Archived from the original on 22 August 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- "Hong Kong Police – The Dangerous Drug Ordinance – Chapter 134". The Hong Kong Police website. The Hong Kong Police. Archived from the original on 5 October 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "Canada now allows prescription heroin in severe opioid addiction". cbc.ca. CBC News. Archived from the original on 15 January 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- "Heroin". NACADA. Archived from the original on 3 December 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- Ochsenbein G (14 February 2014). "'Federal dealer' on 20 years of heroin scheme". SWI swissinfo.ch. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- "List of Drugs for an Urgent Public Health Need". Health Canada. 28 June 2017. Archived from the original on 6 December 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- Poisons Standard October 2015 "Poisons Standard October 2015". Commonwealth of Australia. Archived from the original on 19 January 2016. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- "Poisons Act" (PDF). Government of Australia. 1964. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2015.

- Ubelacker S (12 March 2012). "Medically prescribed heroin more cost-effective than methadone, study suggests". The Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 16 April 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- "Heroin Legal Status". Vaults of Erowid. Erowid. Archived from the original on 14 May 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- "Title 21 of the Code of Federal Regulations (21 CFR) 1308.11". 18 October 2012. Archived from the original on 27 August 2009.

(CSA Sched I) with changes through 77 FR 64032

{{cite web}}: External link in|quote= - "Oregon decriminalizes possession of hard drugs, as four other states legalize recreational marijuana". The Washington Post. 5 November 2020.

- "Oregon becomes first US state to decriminalize possession of hard drugs". The Guardian. 4 November 2020.

- "Turkey Travel Advice". GOV.UK. Archived from the original on 7 June 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. "How is heroin linked to prescription drug abuse?". Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- "Opioid Data Analysis | Drug Overdose | CDC Injury Center". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- "What's A Pill Mill?". Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- "Heroin—Illicit Drug Report" (PDF). Government of Australia. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 February 2014. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- "Afghanistan opium survey – 2004" (PDF). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2006. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- McGirk T (2 August 2004). "Terrorism's Harvest: How al-Qaeda is tapping into the opium trade to finance its operations and destabilize Afghanistan". Time Asia. Archived from the original on 23 January 2007. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- "World failing to dent heroin trade, U.N. warns". CNN. 21 October 2009. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- Andy McSmith and Phil Reeves. "Afghanistan regains its Title as World's biggest Heroin Dealer" in The Independent, 22 June 2003

- North A (10 February 2004). "The drugs threat to Afghanistan". BBC. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- Gall C (3 September 2006). "Opium Harvest at Record Level in Afghanistan". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 December 2007. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- Walsh D (30 August 2007). "UN horrified by surge in opium trade in Helmand". Guardian. London. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- Government of Colombia (July 2015). "Coca cultivation survey" (PDF). Report. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). p. 67. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- "50% of the Heroin consumed in the United States is produced in Mexico". The Yucatan Times. 26 November 2014. Archived from the original on 2 November 2015.

- Yagoub M (26 May 2016). "Sinaloa Cartel's Takeover of US Heroin Market Questionable". Website. InSight Crime. Archived from the original on 27 May 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- "2015 National Drug Threat Assessment Summary" (PDF). Drug Enforcement Administration. United States Department of Justice: Drug Enforcement Administration. October 2015. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

Mexican TCOs pose the greatest criminal drug threat to the United States; no other group is currently positioned to challenge them. These Mexican poly-drug organizations traffic heroin, methamphetamine, cocaine, and marijuana throughout the United States, using established transportation routes and distribution networks. ... While all of these Mexican TCOs transport wholesale quantities of illicit drugs into the United States, the Sinaloa Cartel appears to be the most active supplier. The Sinaloa Cartel leverages its expansive resources and dominance in Mexico to facilitate the smuggling and transportation of drugs throughout the United States.

- Berthiaume L (20 November 2014). "U.S. raises alarm over Afghan heroin flowing through Canada". Ottawa Citizen. Archived from the original on 15 June 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- Editorial Board (26 October 2014). "Afghanistan's Unending Addiction". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 August 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- "Country Profile: Pakistan". United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- Eric C. Schneider, Smack: Heroin and the American City, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008, chapter one

- "War Views: Afghan heroin trade will live on". Richard Davenport-Hines. BBC. October 2001. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- "Haji Bagcho Sentenced To Life in Prison on Narco-Terrorism, Drug Trafficking Charges – Funded Taliban, Responsible for Almost 20 Percent of World's Heroin Production, More Than a Quarter-Billion in Drug Proceeds, Property Forfeited". The Aiken Leader. Archived from the original on 15 June 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- "Haji Bagcho Convicted by Federal Jury in Washington, D.C., on Drug Trafficking and Narco-terrorism Charges – Afghan National Trafficked More Than 123,000 Kilograms of Heroin in 2006". US Department of Justice. 13 March 2012. Archived from the original on 13 July 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- "Haji Bagcho Sentenced to Life in Prison on Trafficking/Narco-Terrorism Charges". Surfky News. Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- Foster Z (23 March 2012). "Haji Bagcho, One of World's Largest Heroin Traffickers, Convicted on Drug Trafficking, Narco-Terrorism Charges". War on Terrorism Online. Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- Tucker E (12 June 2012). "Afghan heroin trafficker gets life in US prison". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- "2007 WORLD DRUG REPORT" (PDF). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 September 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2008). Annual report: the state of the drugs problem in Europe (PDF). Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. p. 70. ISBN 978-92-9168-324-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 April 2013.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2008). World drug report (PDF). United Nations Publications. p. 49. ISBN 978-92-1-148229-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2008.

- Le Page M (18 May 2015). "Home-brew heroin: soon anyone will be able to make illegal drugs". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 13 April 2016.

- Service RF (25 June 2015). "Final step in sugar-to-morphine conversion deciphered". Science. Archived from the original on 21 August 2015.

External links

- Heroin at Curlie

- NIDA InfoFacts on Heroin

- ONDCP Drug Facts

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal – Heroin

- BBC Article entitled 'When Heroin Was Legal'. References to the United Kingdom and the United States

- Drug-poisoning Deaths Involving Heroin: United States, 2000–2013 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.

- Heroin Trafficking in the United States (2016) by Kristin Finklea, Congressional Research Service.