Methyl salicylate

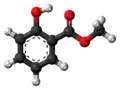

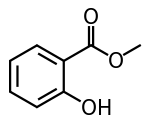

Methyl salicylate (oil of wintergreen or wintergreen oil) is an organic compound with the formula C8H8O3. It is the methyl ester of salicylic acid. It is a colorless, viscous liquid with a sweet, fruity odor reminiscent of root beer (in which it is used as a flavoring),[4] but often associatively called "minty", as it is an ingredient in mint candies.[5] It is produced by many species of plants, particularly wintergreens. It is also produced synthetically, used as a fragrance and as a flavoring agent.

| |||

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Methyl 2-hydroxybenzoate | |||

Other names

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.925 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID |

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C8H8O3 | |||

| Molar mass | 152.149 g/mol | ||

| Appearance | Colorless liquid | ||

| Odor | Sweet, rooty | ||

| Density | 1.174 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | −8.6 °C (16.5 °F; 264.5 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 222 °C (432 °F; 495 K)[1] Decomposes at 340–350 °C[2] | ||

| 0.639 g/L (21 °C) 0.697 g/L (30 °C)[2] | |||

| Solubility | Miscible in organic solvents | ||

| Solubility in acetone | 10.1 g/g (30 °C)[2] | ||

| Vapor pressure | 1 mmHg (54 °C)[1] | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 9.8[3] | ||

| −8.630×10−5 cm3/mol | |||

Refractive index (nD) |

1.538 | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |||

Main hazards |

Harmful | ||

| GHS labelling: | |||

[1] [1] | |||

| Warning | |||

| H302[1] | |||

| P264, P270, P280, P301+P312, P302+P352, P305+P351+P338, P321, P330, P332+P313, P337+P313, P362, P501 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | 96 °C (205 °F; 369 K)[1] | ||

| 452.7 °C (846.9 °F; 725.8 K)[1] | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |||

Biosynthesis and occurrence

Methyl salicylate was first isolated (from the plant Gaultheria procumbens) in 1843 by the French chemist Auguste André Thomas Cahours (1813–1891), who identified it as an ester of salicylic acid and methanol.[6][7]

The biosynthesis of methyl salicylate arises via the hydroxylation of benzoic acid by a cytochrome P450 followed by methylation by a methylase enzyme.[8]

Methyl salicylate as a plant metabolite

Many plants produce methyl salicylate in small quantities. Methyl salicylate levels are often upregulated in response to biotic stress, especially infection by pathogens, where it plays a role in the induction of resistance. Methyl salicylate is believed to function by being metabolized to the plant hormone salicylic acid. Since methyl salicylate is volatile, these signals can spread through the air to distal parts of the same plant or even to neighboring plants, whereupon they can function as a mechanism of plant-to-plant communication, "warning" neighbors of danger.[9] Methyl salicylate is also released in some plants when they are damaged by herbivorous insects, where they may function as a cue aiding in the recruitment of predators.[10]

Some plants produce methyl salicylate in larger quantities, where it likely involved in direct defense against predators or pathogens. Examples of this latter class include: some species of the genus Gaultheria in the family Ericaceae, including Gaultheria procumbens, the wintergreen or eastern teaberry; some species of the genus Betula in the family Betulaceae, particularly those in the subgenus Betulenta such as B. lenta, the black birch; all species of the genus Spiraea in the family Rosaceae, also called the meadowsweets; species of the genus Polygala in the family Polygalaceae. Methyl salicylate can also be a component of floral scents, especially in plants dependent on nocturnal pollinators like moths,[11] scarab beetles, and (nocturnal) bees.[12]

Commercial production

Methyl salicylate can be produced by esterifying salicylic acid with methanol.[13] Commercial methyl salicylate is now synthesized, but in the past, it was commonly distilled from the twigs of Betula lenta (sweet birch) and Gaultheria procumbens (eastern teaberry or wintergreen).

Uses

Methyl salicylate is used in high concentrations as a rubefacient and analgesic in deep heating liniments (such as Bengay) to treat joint and muscular pain. Randomised double blind trials report that evidence of its effectiveness is weak, but stronger for acute pain than chronic pain, and that effectiveness may be due entirely to counterirritation. However, in the body it metabolizes into salicylates, including salicylic acid, a known NSAID.[14][15][16]

Methyl salicylate is used in low concentrations (0.04% and under)[17] as a flavoring agent in root beer,[4] chewing gum and mints. When mixed with sugar and dried, it is a potentially entertaining source of triboluminescence, for example by crushing Wint-O-Green Life Savers in a dark room. When crushed, sugar crystals emit light; methyl salicylate amplifies the spark because it fluoresces, absorbing ultraviolet light and re-emitting it in the visible spectrum.[18][19] It is used as an antiseptic in Listerine mouthwash produced by the Johnson & Johnson company.[20] It provides fragrance to various products and as an odor-masking agent for some organophosphate pesticides.

Methyl salicylate is also used as a bait for attracting male orchid bees for study, which apparently gather the chemical to synthesize pheromones,[21] and to clear plant or animal tissue samples of color, and as such is useful for microscopy and immunohistochemistry when excess pigments obscure structures or block light in the tissue being examined. This clearing generally only takes a few minutes, but the tissue must first be dehydrated in alcohol.[22] It has also been discovered that methyl salicylate works as a kairomone that attracts some insects, such as the spotted lanternfly.[23]

Additional applications include: used as a simulant or surrogate for the research of chemical warfare agent sulfur mustard, due to its similar chemical and physical properties,[24] in restoring (at least temporarily) the elastomeric properties of old rubber rollers, especially in printers,[25] as a transfer agent in printmaking (to release toner from photocopied images and apply them to other surfaces),[26] and as a penetrating oil to loosen rusted parts.

Safety and toxicity

Methyl salicylate is potentially deadly, especially for young children who may accidentally ingest preparations containing methyl salicylate such as an essential oil solution. A single teaspoon (5 mL) of methyl salicylate contains approximately 6 g of salicylate,[27] which is equivalent to almost twenty 300 mg aspirin tablets (5 mL × 1.174 g/mL = 5.87 g). Toxic ingestions of salicylates typically occur with doses of approximately 150 mg/kg body weight. This can be achieved with 1 mL of oil of wintergreen, which equates to 140 mg/kg of salicylates for a 10 kg child (22 lbs).[28] The lowest published lethal dose is 101 mg/kg body weight in adult humans,[29][30] (or 7.07 grams for a 70 kg adult). It has proven fatal to small children in doses as small as 4 mL.[17] A seventeen-year-old cross-country runner at Notre Dame Academy on Staten Island died in April 2007 after her body absorbed methyl salicylate through excessive use of topical muscle-pain relief products (using multiple patches against the manufacturer's instructions).[31]

Most instances of human toxicity due to methyl salicylate are a result of overapplication of topical analgesics, especially involving children. Salicylate, the major metabolite of methyl salicylate, may accumulate in blood, plasma or serum to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients or to assist in an autopsy.[32]

Compendial status

See also

References

- Sigma-Aldrich Co., Methyl salicylate.

- "Methyl salicylate". chemister.ru. Archived from the original on 2014-05-24. Retrieved 2014-05-23.

- Scully, F. E.; Hoigné, J. (January 1987). "Rate constants for reactions of singlet oxygen with phenols and other compounds in water". Chemosphere. 16 (4): 681–694. Bibcode:1987Chmsp..16..681S. doi:10.1016/0045-6535(87)90004-X.

- Markus, John R. (13 February 2020). "Determination of Methyl Salicylate in Root Beer". Journal of AOAC International. 57 (4): 1002–1004. doi:10.1093/jaoac/57.4.1002. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- "The Good Scents Company - Aromatic/Hydrocarbon/Inorganic Ingredients Catalog information". Archived from the original on 2019-12-06. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- Cahours, A. A. T. (1843). "Recherches sur l'huile de Gaultheria procumbens" [Investigations into the oil of Gaultheria procumbens]. Comptes Rendus. 16: 853–856. Archived from the original on 2015-11-24. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- Cahours, A. A. T. (1843). "Sur quelques réactions du salicylate de méthylène" [On some reactions of methyl salicylate]. Comptes Rendus. 17: 43–47. Archived from the original on 2015-11-25. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- Vogt, T. (2010). "Phenylpropanoid Biosynthesis". Molecular Plant. 3: 2–20. doi:10.1093/mp/ssp106. PMID 20035037.

- Shulaev, V.; Silverman, P.; Raskin, I. (1997). "Airborne signalling by methyl salicylate in plant pathogen resistance". Nature. 385 (6618): 718–721. Bibcode:1997Natur.385..718S. doi:10.1038/385718a0. S2CID 4370291.

- James, D. G.; Price, T. S. (2004). "Field-testing of methyl salicylate for recruitment and retention of beneficial insects in grapes and hops". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 30 (8): 1613–1628. doi:10.1023/B:JOEC.0000042072.18151.6f. PMID 15537163. S2CID 36124603.

- Knudsen, J. T.; Tollsten, L. (1993). "Trends in floral scent chemistry in pollination syndromes: floral scent composition in moth-pollinated taxa". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. Oxford Academic. 113 (3): 263–284. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1993.tb00340.x.

- Cordeiro, G. D.; Fernandes dos Santos, I. G.; da Silva, C. I.; Schlindwein, C.; Alves-dos-Santos, I.; Dötterl, S. (2019). "Nocturnal floral scent profiles of Myrtaceae fruit crops". Phytochemistry. 162: 193–198. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2019.03.011. PMID 30939396. S2CID 92997657.

- Boullard, Olivier; Leblanc, Henri; Besson, Bernard (2012). "Salicylic Acid". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a23_477.

- "Topical analgesics introduction". Medicine.ox.ac.uk. 2003-05-26. Archived from the original on 2012-08-04. Retrieved 2012-11-07.

- Mason, L.; Moore, R. A.; Edwards, J. E.; McQuay, H. J.; Derry, S.; Wiffen, P. J. (2004). "Systematic review of efficacy of topical rubefacients containing salicylates for the treatment of acute and chronic pain". British Medical Journal. 328 (7446): 995. doi:10.1136/bmj.38040.607141.EE. PMC 404501. PMID 15033879.

- Tramer, M. R. (2004). "It's not just about rubbing—topical capsaicin and topical salicylates may be useful as adjuvants to conventional pain treatment". British Medical Journal. 328 (7446): 998. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7446.998. PMC 404503. PMID 15105325.

- Wintergreen Archived 2018-03-19 at the Wayback Machine at Drugs.com

- Harvey, E. N. (1939). "The luminescence of sugar wafers". Science. 90 (2324): 35–36. Bibcode:1939Sci....90...35N. doi:10.1126/science.90.2324.35. PMID 17798129.

- "Why do Wint-O-Green Life Savers spark in the dark?". HowStuffWorks. Archived from the original on 2007-08-17. Retrieved 2008-04-27.

- Listerine. "Original Listerine Antiseptic Mouthwash". Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- Schiestl, F. P.; Roubik, D. W. (2004). "Odor Compound Detection in Male Euglossine Bees". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 29 (1): 253–257. doi:10.1023/A:1021932131526. PMID 12647866. S2CID 2845587.

- Altman, J. S.; Tyrer, N. M. (1980). "Filling selected neurons with cobalt through cut axons". In Strausfeld, N. J.; Miller, T. A. (eds.). Neuroanatomical Techniques. Springer-Verlag. pp. 373–402.

- Cooperband, Miriam F.; Wickham, Jacob; Cleary, Kaitlin; Spichiger, Sven-Erik; Zhang, Longwa; Baker, John; Canlas, Isaiah; Derstine, Nathan; Carrillo, Daniel (2019-03-21). "Discovery of three kairomones in relation to trap and lure development for spotted lanternfly (Hemiptera: Fulgoridae)". Journal of Economic Entomology. 112 (2): 671–682. doi:10.1093/jee/toy412. ISSN 0022-0493. PMID 30753676.

- Bartlet-Hunt, S. L.; Knappe, D. R. U.; Barlaz, M. A. (2008). "A Review of Chemical Warfare Agent Simulants for the Study of Environmental Behaviour". Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology. 38 (2): 112–136. doi:10.1080/10643380701643650. S2CID 97484598.

- "MG Chemicals – Rubber Renue Safety Data Sheet" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-26.

- Modrak, Rebekah and Bill Anthes. "Image Transfer & Rubbing Techniques – Reframing Photography". www.reframingphotography.com. Retrieved 2021-09-07.

- "Salicylate Poisoning – Patient UK". Patient.info. 2011-04-20. Archived from the original on 2015-08-18. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- Hoffman, R. (2015). Goldfrank's Toxicologic Emergencies (10th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. pp. 915–922. ISBN 978-0-07-180184-3.

- "Safety (MSDS) data for methyl salicylate". University of Oxford Department of Chemistry MSDS. 2010-09-15. Archived from the original on 2011-06-07. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- "Methyl Salicyclate" (PDF). CAMEO Chemicals. June 1999. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 Dec 2016. Retrieved 24 Apr 2023.

- "Muscle-Pain Reliever Is Blamed For Staten Island Runner's Death". New York Times. 10 June 2007. Archived from the original on 18 January 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- Baselt, R. (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 1012–1014. ISBN 978-0-9626523-7-0.

- The British Pharmacopoeia Secretariat (2009). "Index, BP 2009" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2009. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- "NIHS Japan". Moldb.nihs.go.jp. Archived from the original on 2013-02-17. Retrieved 2013-07-01.