Pantheism

Pantheism is the philosophical religious belief that reality,[1] the universe and the cosmos are identical to divinity and a supreme being or entity. The physical universe is thus understood as an immanent deity, still expanding and creating, which has existed since the beginning of time.[2] The term 'pantheist' designates one who holds both that everything constitutes a unity and that this unity is divine, consisting of an all-encompassing, manifested god or goddess.[3][4] All astronomical objects are thence viewed as parts of a sole deity.

The worship of all gods of every religion is another definition, but it is more precisely termed Omnism.[5] Pantheist belief does not recognize a distinct personal god,[6] anthropomorphic or otherwise, but instead characterizes a broad range of doctrines differing in forms of relationships between reality and divinity.[7] Pantheistic concepts date back thousands of years, and pantheistic elements have been identified in various religious traditions. The term pantheism was coined by mathematician Joseph Raphson in 1697[8][9] and since then, it has been used to describe the beliefs of a variety of people and organizations.

Pantheism was popularized in Western culture as a theology and philosophy based on the work of the 17th-century philosopher Baruch Spinoza, in particular, his book Ethics.[10] A pantheistic stance was also taken in the 16th century by philosopher and cosmologist Giordano Bruno.[11]

Etymology

Pantheism derives from the Greek word πᾶν pan (meaning "all, of everything") and θεός theos (meaning "god, divine"). The first known combination of these roots appears in Latin, in Joseph Raphson's 1697 book De Spatio Reali seu Ente Infinito,[9] where he refers to the "pantheismus" of Spinoza and others.[8] It was subsequently translated into English as "pantheism" in 1702.

Definitions

| Part of a series on |

| Spirituality |

|---|

| Outline |

| Influences |

| Research |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Irreligion |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Theism |

|---|

There are numerous definitions of pantheism. Some consider it a theological and philosophical position concerning God.[14]: p.8

A doctrine which identifies God with the universe, or regards the universe as a manifestation of God.

Pantheism is the view that everything is part of an all-encompassing, immanent God. All forms of reality may then be considered either modes of that Being, or identical with it.[15] Some hold that pantheism is a non-religious philosophical position. To them, pantheism is the view that the Universe (in the sense of the totality of all existence) and God are identical.[16]

History

Pre-modern times

Early traces of pantheist thought can be found within animistic beliefs and tribal religions throughout the world as an expression of unity with the divine, specifically in beliefs that have no central polytheist or monotheist personas. Hellenistic theology makes early recorded reference to pantheism within the ancient Greek religion of Orphism, where pan (the all) is made cognate with the creator God Phanes (symbolizing the universe),[17] and with Zeus, after the swallowing of Phanes.[18]

Pantheistic tendencies existed in a number of Gnostic groups, with pantheistic thought appearing throughout the Middle Ages.[19] These included the beliefs of mystics such as Ortlieb of Strasbourg, David of Dinant, Amalric of Bena, and Eckhart.[19]: pp. 620–621

The Catholic Church has long regarded pantheistic ideas as heresy.[20][21] Sebastian Franck was considered an early Pantheist.[22] Giordano Bruno, an Italian friar who evangelized about a transcendent and infinite God, was burned at the stake in 1600 by the Roman Inquisition. He has since become known as a celebrated pantheist and martyr of science.[23][24]

Baruch Spinoza

In the West, pantheism was formalized as a separate theology and philosophy based on the work of the 17th-century philosopher Baruch Spinoza.[14]: p.7 Spinoza was a Dutch philosopher of Portuguese descent raised in the Sephardi Jewish community in Amsterdam.[26] He developed highly controversial ideas regarding the authenticity of the Hebrew Bible and the nature of the Divine, and was effectively excluded from Jewish society at age 23, when the local synagogue issued a herem against him.[27] A number of his books were published posthumously, and shortly thereafter included in the Catholic Church's Index of Forbidden Books. The breadth and importance of Spinoza's work would not be realized for many years – as the groundwork for the 18th-century Enlightenment[28] and modern biblical criticism,[29] including modern conceptions of the self and the universe.[30]

In the posthumous Ethics, "Spinoza wrote the last indisputable Latin masterpiece, and one in which the refined conceptions of medieval philosophy are finally turned against themselves and destroyed entirely."[31] In particular, he opposed René Descartes' famous mind–body dualism, the theory that the body and spirit are separate.[32] Spinoza held the monist view that the two are the same, and monism is a fundamental part of his philosophy. He was described as a "God-intoxicated man," and used the word God to describe the unity of all substance.[32] This view influenced philosophers such as Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, who said, "You are either a Spinozist or not a philosopher at all."[33] Spinoza earned praise as one of the great rationalists of 17th-century philosophy[34] and one of Western philosophy's most important thinkers.[35] Although the term "pantheism" was not coined until after his death, he is regarded as the most celebrated advocate of the concept.[36] Ethics was the major source from which Western pantheism spread.[10]

Heinrich Heine, in his Concerning the History of Religion and Philosophy in Germany (1833–36), remarked that "I don't remember now where I read that Herder once exploded peevishly at the constant preoccupation with Spinoza, "If Goethe would only for once pick up some other Latin book than Spinoza!" But this applies not only to Goethe; quite a number of his friends, who later became more or less well-known as poets, paid homage to pantheism in their youth, and this doctrine flourished actively in German art before it attained supremacy among us as a philosophic theory."

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe rejected Jacobi’s personal belief in God as the "hollow sentiment of a child’s brain" (Goethe 15/1: 446) and, in the "Studie nach Spinoza" (1785/86), proclaimed the identity of existence and wholeness. When Jacobi speaks of Spinoza’s "fundamentally stupid universe" (Jacobi [31819] 2000: 312), Goethe praises nature as his "idol" (Goethe 14: 535).[37]

In their The Holy Family (1844) Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels note, "Spinozism dominated the eighteenth century both in its later French variety, which made matter into substance, and in deism, which conferred on matter a more spiritual name.... Spinoza's French school and the supporters of deism were but two sects disputing over the true meaning of his system...."

In George Henry Lewes's words (1846), "Pantheism is as old as philosophy. It was taught in the old Greek schools — by Plato, by St. Augustine, and by the Jews. Indeed, one may say that Pantheism, under one of its various shapes, is the necessary consequence of all metaphysical inquiry, when pushed to its logical limits; and from this reason do we find it in every age and nation. The dreamy contemplative Indian, the quick versatile Greek, the practical Roman, the quibbling Scholastic, the ardent Italian, the lively Frenchman, and the bold Englishman, have all pronounced it as the final truth of philosophy. Wherein consists Spinoza's originality? — what is his merit? — are natural questions, when we see him only lead to the same result as others had before proclaimed. His merit and originality consist in the systematic exposition and development of that doctrine — in his hands, for the first time, it assumes the aspect of a science. The Greek and Indian Pantheism is a vague fanciful doctrine, carrying with it no scientific conviction; it may be true — it looks true — but the proof is wanting. But with Spinoza there is no choice: if you understand his terms, admit the possibility of his science, and seize his meaning; you can no more doubt his conclusions than you can doubt Euclid; no mere opinion is possible, conviction only is possible."[38]

S. M. Melamed (1933) noted, "It may be observed, however, that Spinoza was not the first prominent monist and pantheist in modern Europe. A generation before him Bruno conveyed a similar message to humanity. Yet Bruno is merely a beautiful episode in the history of the human mind, while Spinoza is one of its most potent forces. Bruno was a rhapsodist and a poet, who was overwhelmed with artistic emotions; Spinoza, however, was spiritus purus and in his method the prototype of the philosopher."[39]

18th century

The first known use of the term "pantheism" was in Latin ("pantheismus"[8]) by the English mathematician Joseph Raphson in his work De Spatio Reali seu Ente Infinito, published in 1697.[9] Raphson begins with a distinction between atheistic "panhylists" (from the Greek roots pan, "all", and hyle, "matter"), who believe everything is matter, and Spinozan "pantheists" who believe in "a certain universal substance, material as well as intelligence, that fashions all things that exist out of its own essence."[40][41] Raphson thought that the universe was immeasurable in respect to a human's capacity of understanding, and believed that humans would never be able to comprehend it.[42] He referred to the pantheism of the Ancient Egyptians, Persians, Syrians, Assyrians, Greek, Indians, and Jewish Kabbalists, specifically referring to Spinoza.[43]

The term was first used in English by a translation of Raphson's work in 1702. It was later used and popularized by Irish writer John Toland in his work of 1705 Socinianism Truly Stated, by a pantheist.[44][19]: pp. 617–618 Toland was influenced by both Spinoza and Bruno, and had read Joseph Raphson's De Spatio Reali, referring to it as "the ingenious Mr. Ralphson's (sic) Book of Real Space".[45] Like Raphson, he used the terms "pantheist" and "Spinozist" interchangeably.[46] In 1720 he wrote the Pantheisticon: or The Form of Celebrating the Socratic-Society in Latin, envisioning a pantheist society that believed, "All things in the world are one, and one is all in all things ... what is all in all things is God, eternal and immense, neither born nor ever to perish."[47][48] He clarified his idea of pantheism in a letter to Gottfried Leibniz in 1710 when he referred to "the pantheistic opinion of those who believe in no other eternal being but the universe".[19][49][50][51]

In the mid-eighteenth century, the English theologian Daniel Waterland defined pantheism this way: "It supposes God and nature, or God and the whole universe, to be one and the same substance—one universal being; insomuch that men's souls are only modifications of the divine substance."[19][52] In the early nineteenth century, the German theologian Julius Wegscheider defined pantheism as the belief that God and the world established by God are one and the same.[19][53]

Pantheism controversy

Between 1785–89, a major controversy about Spinoza's philosophy arose between the German philosophers Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi (a critic) and Moses Mendelssohn (a defender). Known in German as the Pantheismusstreit (pantheism controversy), it helped spread pantheism to many German thinkers.[54] A 1780 conversation with the German dramatist Gotthold Ephraim Lessing led Jacobi to a protracted study of Spinoza's works. Lessing stated that he knew no other philosophy than Spinozism. Jacobi's Über die Lehre des Spinozas (1st ed. 1785, 2nd ed. 1789) expressed his strenuous objection to a dogmatic system in philosophy, and drew upon him the enmity of the Berlin group, led by Mendelssohn. Jacobi claimed that Spinoza's doctrine was pure materialism, because all Nature and God are said to be nothing but extended substance. This, for Jacobi, was the result of Enlightenment rationalism and it would finally end in absolute atheism. Mendelssohn disagreed with Jacobi, saying that pantheism shares more characteristics of theism than of atheism. The entire issue became a major intellectual and religious concern for European civilization at the time.[55]

Willi Goetschel argues that Jacobi's publication significantly shaped Spinoza's wide reception for centuries following its publication, obscuring the nuance of Spinoza's philosophic work.[56]

Growing influence

During the beginning of the 19th century, pantheism was the viewpoint of many leading writers and philosophers, attracting figures such as William Wordsworth and Samuel Coleridge in Britain; Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Schelling and Hegel in Germany; Knut Hamsun in Norway; and Walt Whitman, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau in the United States. Seen as a growing threat by the Vatican, in 1864 it was formally condemned by Pope Pius IX in the Syllabus of Errors.[57]

A letter written in 1886 by William Herndon, Abraham Lincoln's law partner, was sold at auction for US$30,000 in 2011.[58] In it, Herndon writes of the U.S. President's evolving religious views, which included pantheism.

"Mr. Lincoln's religion is too well known to me to allow of even a shadow of a doubt; he is or was a Theist and a Rationalist, denying all extraordinary – supernatural inspiration or revelation. At one time in his life, to say the least, he was an elevated Pantheist, doubting the immortality of the soul as the Christian world understands that term. He believed that the soul lost its identity and was immortal as a force. Subsequent to this he rose to the belief of a God, and this is all the change he ever underwent."[58][59]

The subject is understandably controversial, but the content of the letter is consistent with Lincoln's fairly lukewarm approach to organized religion.[59]

Comparison with non-Christian religions

Some 19th-century theologians thought that various pre-Christian religions and philosophies were pantheistic. They thought Pantheism was similar to ancient Hinduism[19]: pp. 618 philosophy of Advaita (non-dualism) to the extent that the 19th-century German Sanskritist Theodore Goldstücker remarked that Spinoza's thought was "... a western system of philosophy which occupies a foremost rank amongst the philosophies of all nations and ages, and which is so exact a representation of the ideas of the Vedanta, that we might have suspected its founder to have borrowed the fundamental principles of his system from the Hindus."[60]

19th-century European theologians also considered Ancient Egyptian religion to contain pantheistic elements and pointed to Egyptian philosophy as a source of Greek Pantheism.[19]: pp. 618–620 The latter included some of the Presocratics, such as Heraclitus and Anaximander.[61] The Stoics were pantheists, beginning with Zeno of Citium and culminating in the emperor-philosopher Marcus Aurelius. During the pre-Christian Roman Empire, Stoicism was one of the three dominant schools of philosophy, along with Epicureanism and Neoplatonism.[62][63] The early Taoism of Laozi and Zhuangzi is also sometimes considered pantheistic, although it could be more similar to Panentheism.[49]

Cheondoism, which arose in the Joseon Dynasty of Korea, and Won Buddhism are also considered pantheistic. The Realist Society of Canada believes that the consciousness of the self-aware universe is reality, which is an alternative view of Pantheism.[64]

20th century

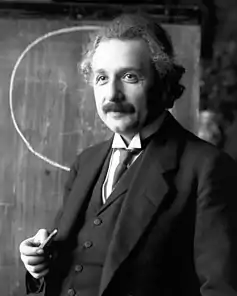

In a letter written to Eduard Büsching (25 October 1929), after Büsching sent Albert Einstein a copy of his book Es gibt keinen Gott ("There is no God"), Einstein wrote, "We followers of Spinoza see our God in the wonderful order and lawfulness of all that exists and in its soul [Beseeltheit] as it reveals itself in man and animal."[65] According to Einstein, the book only dealt with the concept of a personal god and not the impersonal God of pantheism.[65] In a letter written in 1954 to philosopher Eric Gutkind, Einstein wrote "the word God is for me nothing more than the expression and product of human weaknesses."[66][67] In another letter written in 1954 he wrote "I do not believe in a personal God and I have never denied this but have expressed it clearly."[66] In Ideas And Opinions, published a year before his death, Einstein stated his precise conception of the word God:

Scientific research can reduce superstition by encouraging people to think and view things in terms of cause and effect. Certain it is that a conviction, akin to religious feeling, of the rationality and intelligibility of the world lies behind all scientific work of a higher order. [...] This firm belief, a belief bound up with a deep feeling, in a superior mind that reveals itself in the world of experience, represents my conception of God. In common parlance this may be described as "pantheistic" (Spinoza).[68]

In the late 20th century, some declared that pantheism was an underlying theology of Neopaganism,[69] and pantheists began forming organizations devoted specifically to pantheism and treating it as a separate religion.[49]

21st century

Dorion Sagan, son of scientist and science communicator Carl Sagan, published the 2007 book Dazzle Gradually: Reflections on the Nature of Nature, co-written with his mother Lynn Margulis. In the chapter "Truth of My Father", Sagan writes that his "father believed in the God of Spinoza and Einstein, God not behind nature, but as nature, equivalent to it."[70]

In 2009, pantheism was mentioned in a Papal encyclical[71] and in a statement on New Year's Day, 2010,[72] criticizing pantheism for denying the superiority of humans over nature and seeing the source of man's salvation in nature.[71]

In 2015 The Paradise Project, an organization "dedicated to celebrating and spreading awareness about pantheism," commissioned Los Angeles muralist Levi Ponce to paint the 75-foot mural in Venice, California near the organization's offices.[73] The mural depicts Albert Einstein, Alan Watts, Baruch Spinoza, Terence McKenna, Carl Jung, Carl Sagan, Emily Dickinson, Nikola Tesla, Friedrich Nietzsche, Ralph Waldo Emerson, W.E.B. Du Bois, Henry David Thoreau, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Rumi, Adi Shankara, and Laozi.[74][75]

Categorizations

There are multiple varieties of pantheism[19][76]: 3 and various systems of classifying them relying upon one or more spectra or in discrete categories.

Degree of determinism

The philosopher Charles Hartshorne used the term Classical Pantheism to describe the deterministic philosophies of Baruch Spinoza, the Stoics, and other like-minded figures.[77] Pantheism (All-is-God) is often associated with monism (All-is-One) and some have suggested that it logically implies determinism (All-is-Now).[32][78][79][80][81] Albert Einstein explained theological determinism by stating,[82] "the past, present, and future are an 'illusion'". This form of pantheism has been referred to as "extreme monism", in which – in the words of one commentator – "God decides or determines everything, including our supposed decisions."[83] Other examples of determinism-inclined pantheisms include those of Ralph Waldo Emerson,[84] and Hegel.[85]

However, some have argued against treating every meaning of "unity" as an aspect of pantheism,[86] and there exist versions of pantheism that regard determinism as an inaccurate or incomplete view of nature. Examples include the beliefs of John Scotus Eriugena,[87] Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling and William James.[88]

Degree of belief

It may also be possible to distinguish two types of pantheism, one being more religious and the other being more philosophical. The Columbia Encyclopedia writes of the distinction:

- "If the pantheist starts with the belief that the one great reality, eternal and infinite, is God, he sees everything finite and temporal as but some part of God. There is nothing separate or distinct from God, for God is the universe. If, on the other hand, the conception taken as the foundation of the system is that the great inclusive unity is the world itself, or the universe, God is swallowed up in that unity, which may be designated nature."[89]

Form of monism

Philosophers and theologians have often suggested that pantheism implies monism.[90] [note 1]

Other

In 1896, J. H. Worman, a theologian, identified seven categories of pantheism: Mechanical or materialistic (God the mechanical unity of existence); Ontological (fundamental unity, Spinoza); Dynamic; Psychical (God is the soul of the world); Ethical (God is the universal moral order, Fichte); Logical (Hegel); and Pure (absorption of God into nature, which Worman equates with atheism).[19]

In 1984, Paul D. Feinberg, professor of biblical and systematic theology at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, also identified seven: Hylozoistic; Immanentistic; Absolutistic monistic; Relativistic monistic; Acosmic; Identity of opposites; and Neoplatonic or emanationistic.[96]

Demographics

Prevalence

According to censuses of 2011, the UK was the country with the most Pantheists.[97] As of 2011, about 1,000 Canadians identified their religion as "Pantheist", representing 0.003% of the population.[98] By 2021, the number of Canadian pantheists had risen to 1,855 (0.005%).[99] In Ireland, Pantheism rose from 202 in 1991,[100] to 1106 in 2002,[100] to 1,691 in 2006,[101] 1,940 in 2011.[102] In New Zealand, there was exactly one pantheist man in 1901.[103] By 1906, the number of pantheists in New Zealand had septupled to 7 (6 male, 1 female).[104] This number had further risen to 366 by 2006.[105]

Age, ethnicity, and gender

The 2021 Canadian census showed that pantheists were somewhat more likely to be in their 20s and 30s compared to the general population. The age group least likely to be pantheist were those aged under 15, who were about four times less likely to be pantheist than the general population.[111]

The 2021 Canadian census also showed that pantheists were less likely to be part of a recognized minority group compared to the general population, with 90.3% of pantheists not being part of any minority group (compared to 73.5% of the general population). The census did not register any pantheists who were Arab, Southeast Asian, West Asian, Korean, or Japanese.[111]

In Canada (2011), there was no gender difference in regards to pantheism.[98] However, in Ireland (2011), pantheists were slightly more likely to be female (1074 pantheists, 0.046% of women) than male (866 pantheists, 0.038% of men).[102] In contrast, Canada (2021) showed pantheists to be slightly more likely to be male, with men representing 51.5% of pantheists.[111]

| Comparison of pantheists in Canada against the general population (2021)[111] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| General population | Pantheists | ||

| Total population | 36,328,480 | 1,855 | |

| Gender | Male | 17,937,165 (49.4%) | 955 (51.5%) |

| Female | 18,391,315 (50.6%) | 895 (48.2%) | |

| Age | 0 to 14 | 5,992,555 (16.5%) | 75 (4%) |

| 15 to 19 | 2,003,200 (5.5%) | 40 (2%) | |

| 20 to 24 | 2,177,860 (6%) | 125 (6.7%) | |

| 25 to 34 | 4,898,625 (13.5%) | 405 (21.8%) | |

| 35 to 44 | 4,872,425 (13.4%) | 380 (20.5%) | |

| 45 to 54 | 4,634,850 (12.8%) | 245 (13.2%) | |

| 55 to 64 | 5,162,365 (14.2%) | 245 13.2%) | |

| 65 and over | 6,586,600 (18.1%) | 325 (17.5%) | |

| Ethnicity | Non-minority | 26,689,275 (73.5%) | 1,675 (90.3%) |

| South Asian | 2,571,400 (7%) | 20 (1.1%) | |

| Chinese | 1,715,770 (4.7%) | 45 (2.4%) | |

| Black | 1,547,870 (4.3%) | 45 (2.4%) | |

| Filipino | 957,355 (2.6%) | 10 (0.5%) | |

| Arab | 694,015 (1.9%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Latin American | 580,235 (1.6%) | 25 (1.3%) | |

| Southeast Asian | 390,340 (1.1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| West Asian | 360,495 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Korean | 218,140 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Japanese | 98,890 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Visible minority, n.i.e. | 172,885 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Multiple visible minorities | 331,805 (0.9%) | 15 (0.8%) | |

Related concepts

Nature worship or nature mysticism is often conflated and confused with pantheism. It is pointed out by at least one expert, Harold Wood, founder of the Universal Pantheist Society, that in pantheist philosophy Spinoza's identification of God with nature is very different from a recent idea of a self identifying pantheist with environmental ethical concerns. His use of the word nature to describe his worldview may be vastly different from the "nature" of modern sciences. He and other nature mystics who also identify as pantheists use "nature" to refer to the limited natural environment (as opposed to man-made built environment). This use of "nature" is different from the broader use from Spinoza and other pantheists describing natural laws and the overall phenomena of the physical world. Nature mysticism may be compatible with pantheism but it may also be compatible with theism and other views.[7] Pantheism has also been involved in animal worship especially in primal religions.[112]

Nontheism is an umbrella term which has been used to refer to a variety of religions not fitting traditional theism, and under which pantheism has been included.[7]

Panentheism (from Greek πᾶν (pân) "all"; ἐν (en) "in"; and θεός (theós) "God"; "all-in-God") was formally coined in Germany in the 19th century in an attempt to offer a philosophical synthesis between traditional theism and pantheism, stating that God is substantially omnipresent in the physical universe but also exists "apart from" or "beyond" it as its Creator and Sustainer.[113]: p.27 Thus panentheism separates itself from pantheism, positing the extra claim that God exists above and beyond the world as we know it.[114] The line between pantheism and panentheism can be blurred depending on varying definitions of God, so there have been disagreements when assigning particular notable figures to pantheism or panentheism.[113]: pp. 71–72, 87–88, 105 [115]

Pandeism is another word derived from pantheism, and is characterized as a combination of reconcilable elements of pantheism and deism.[116] It assumes a Creator-deity that is at some point distinct from the universe and then transforms into it, resulting in a universe similar to the pantheistic one in present essence, but differing in origin.

Panpsychism is the philosophical view that consciousness, mind, or soul is a universal feature of all things.[117] Some pantheists also subscribe to the distinct philosophical views hylozoism (or panvitalism), the view that everything is alive, and its close neighbor animism, the view that everything has a soul or spirit.[118]

Pantheism in religion

Traditional religions

Many traditional and folk religions including African traditional religions[119] and Native American religions[120][121] can be seen as pantheistic, or a mixture of pantheism and other doctrines such as polytheism and animism. According to pantheists, there are elements of pantheism in some forms of Christianity.[122][123][124]

Ideas resembling pantheism existed in Eastern religions before the 18th century (notably Sikhism, Hinduism, Confucianism, and Taoism). Although there is no evidence that these influenced Spinoza's work, there is such evidence regarding other contemporary philosophers, such as Leibniz, and later Voltaire.[125][126] In the case of Hinduism, pantheistic views exist alongside panentheistic, polytheistic, monotheistic, and atheistic ones.[127][128][129] In the case of Sikhism, stories attributed to Guru Nanak suggest that he believed God was everywhere in the physical world, and the Sikh tradition typically describes God as the preservative force within the physical world, present in all material forms, each created as a manifestation of God. However, Sikhs view God as the transcendent creator,[130] "immanent in the phenomenal reality of the world in the same way in which an artist can be said to be present in his art".[131] This implies a more panentheistic position.

Spirituality and new religious movements

Pantheism is popular in modern spirituality and new religious movements, such as Neopaganism and Theosophy.[132] Two organizations that specify the word pantheism in their title formed in the last quarter of the 20th century. The Universal Pantheist Society, open to all varieties of pantheists and supportive of environmental causes, was founded in 1975.[133] The World Pantheist Movement is headed by Paul Harrison, an environmentalist, writer and a former vice president of the Universal Pantheist Society, from which he resigned in 1996. The World Pantheist Movement was incorporated in 1999 to focus exclusively on promoting naturalistic pantheism – a strict metaphysical naturalistic version of pantheism,[134] considered by some a form of religious naturalism.[135] It has been described as an example of "dark green religion" with a focus on environmental ethics.[136]

See also

- Astrotheology

- Animism

- Biocentrism (ethics)

- Irreligion

- List of pantheists

- Monism

- Mother nature

- Panentheism

- Theopanism, a term that is philosophically distinct but derived from the same root words

Notes

- Different types of monism include:[91][92]

- Substance monism, "the view that the apparent plurality of substances is due to different states or appearances of a single substance".[91]

- Attributive monism, "the view that whatever the number of substances, they are of a single ultimate kind".[91]

- Partial monism, "within a given realm of being (however many there may be) there is only one substance".[91]

- Existence monism, the view that there is only one concrete object token (The One, "Τὸ Ἕν" or the Monad).[93]

- Priority monism, "the whole is prior to its parts" or "the world has parts, but the parts are dependent fragments of an integrated whole."[92]

- Property monism: the view that all properties are of a single type (e.g. only physical properties exist).

- Genus monism: "the doctrine that there is a highest category; e.g., being".[92]

- Metaphysical dualism, which asserts that there are two ultimately irreconcilable substances or realities such as Good and Evil, for example, Manichaeism.[94]

- Metaphysical pluralism, which asserts three or more fundamental substances or realities.[94]

- Nihilism, negates any of the above categories (substances, properties, concrete objects, etc.).

- Idealism, phenomenalism, or mentalistic monism, which holds that only mind or spirit is real.[94]

- Neutral monism, which holds that one sort of thing fundamentally exists,[95] to which both the mental and the physical can be reduced.

- Material monism (also called Physicalism and Materialism), which holds that only the physical is real, and that the mental or spiritual can be reduced to the physical:[94][95]

- a. Eliminative materialism, according to which everything is physical and mental things do not exist.[95]

- b. Reductive physicalism, according to which mental things do exist and are a kind of physical thing,[95] Such as Behaviourism, Type-identity theory and Functionalism.

References

- "Pantheism – Definition, Meaning & Synonyms". Vocabulary.com. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- The New Oxford Dictionary of English. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1998. p. 1341. ISBN 978-0-19-861263-6.

- Encyclopedia of Philosophy ed. Paul Edwards. New York: Macmillan and Free Press. 1967. p. 34.

- Reid-Bowen, Paul (2016). Goddess as Nature: Towards a Philosophical Thealogy. Taylor & Francis. p. 70. ISBN 978-1317126348.

- "Definition of Pantheism".

- Charles Taliaferro; Paul Draper; Philip L. Quinn (eds.). A Companion to Philosophy of Religion. p. 340.

They deny that God is 'totally other' than the world or ontologically distinct from it.

- Levine 1994, pp. 44, 274–275:

- "The idea that Unity that is rooted in nature is what types of nature mysticism (e.g. Wordsworth, Robinson Jeffers, Gary Snyder) have in common with more philosophically robust versions of pantheism. It is why nature mysticism and philosophical pantheism are often conflated and confused for one another."

- "[Wood's] pantheism is distant from Spinoza's identification of God with nature, and much closer to nature mysticism. In fact it is nature mysticism."

- "Nature mysticism, however, is as compatible with theism as it is with pantheism."

- Taylor, Bron (2008). Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature. A&C Black. pp. 1341–1342. ISBN 978-1441122780. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- Ann Thomson; Bodies of Thought: Science, Religion, and the Soul in the Early Enlightenment, 2008, page 54.

- Lloyd, Genevieve (1996). Routledge Philosophy GuideBook to Spinoza and The Ethics. Routledge Philosophy Guidebooks. Routledge. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-415-10782-2.

- Birx, Jams H. (11 November 1997). "Giordano Bruno". Mobile, AL: The Harbinger. Archived from the original on 27 July 2017. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

Bruno was burned to death at the stake for his pantheistic stance and cosmic perspective.

- Pearsall, Judy (1998). The New Oxford Dictionary Of English (1st ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 1341. ISBN 978-0-19-861263-6.

- Edwards, Paul (1967). Encyclopedia of Philosophy. New York: Macmillan. p. 34.

- Picton, James Allanson (1905). Pantheism: its story and significance. Chicago: Archibald Constable & CO LTD. ISBN 978-1419140082.

- Owen, H. P. Concepts of Deity. London: Macmillan, 1971, p. 65.

- The New Oxford Dictionary Of English. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1998. p. 1341. ISBN 978-0-19-861263-6.

- Damascius, referring to the theology delivered by Hieronymus and Hellanicus in "The Theogonies". sacred-texts.com.:"... the theology now under discussion celebrates as Protogonus (First-born) [Phanes], and calls him Dis, as the disposer of all things, and the whole world: upon that account he is also denominated Pan."

- Betegh, Gábor, The Derveni Papyrus, Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp. 176–178 ISBN 978-0-521-80108-9

- Worman, J. H., "Pantheism", in Cyclopædia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature, Volume 1, John McClintock, James Strong (Eds), Harper & Brothers, 1896, pp. 616–624.

- Collinge, William, Historical Dictionary of Catholicism, Scarecrow Press, 2012, p 188, ISBN 9780810879799.

- "What is pantheism?". catholic.com. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017.

- Kołakowski, Leszek (11 June 2009). The Two Eyes of Spinoza & Other Essays on Philosophers – Leszek Kołakowski – Google Books. St. Augustine's Press. ISBN 9781587318757. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- McIntyre, James Lewis, Giordano Bruno, Macmillan, 1903, p 316.

- "Bruno Was a Martyr for Magic, Not Science | Science 2.0". 27 August 2014.

-

- Fraser, Alexander Campbell "Philosophy of Theism", William Blackwood and Sons, 1895, p 163.

- Gottlieb, Anthony (18 July 1999). "God Exists, Philosophically (review of "Spinoza: A Life" by Steven Nadler)". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- "Why Spinoza Was Excommunicated". National Endowment for the Humanities. 1 September 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- Yalom, Irvin (21 February 2012). "The Spinoza Problem". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- Yovel, Yirmiyahu (1992). Spinoza and Other Heretics: The Adventures of Immanence. Princeton University Press. p. 3.

- "Destroyer and Builder". The New Republic. 3 May 2012. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- Scruton 1986 (2002 ed.), ch. 1, p.32.

- Plumptre, Constance (1879). General sketch of the history of pantheism, Volume 2. London: Samuel Deacon and Co. pp. 3–5, 8, 29. ISBN 9780766155022.

- Hegel's History of Philosophy. SUNY Press. 2003. ISBN 9780791455432. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- Scruton 1986 (2002 ed.), ch. 2, p.26

- Deleuze, Gilles (1990). "(translator's preface)". Expressionism in Philosophy: Spinoza. Zone Books. Referred to as "the prince" of the philosophers.

- Shoham, Schlomo Giora (2010). To Test the Limits of Our Endurance. Cambridge Scholars. p. 111. ISBN 978-1443820684.

- Bollacher, Martin (2020). "Pantheism". In Kirchhoff, T. (ed.). Online Encyclopedia Philosophy of Nature. Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg. p. 5. doi:10.11588/oepn.2020.0.76525.; "Goethe 14" and "Goethe 15/1" in the passage refers to volumes of Johann Wolfgang Goethe 1987–2013: Sämtliche Werke. Briefe, Tagebücher und Gespräche. Vierzig Bände. Frankfurt/M., Deutscher Klassiker Verlag.

- Lewes, George Henry (1846). A Biographical History of Philosophy, Volumes III & IV. London: C. Knight & Company.

- Melamed, S. M. (1933). Spinoza and Buddha: Visions of a Dead God. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Raphson, Joseph (1697). De spatio reali (in Latin). Londini. p. 2.

- Suttle, Gary. "Joseph Raphson: 1648–1715". Pantheist Association for Nature. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- Koyré, Alexander (1957). From the Closed World to the Infinite Universe. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins Press. pp. 190–204. ISBN 978-0801803475.

- Bennet, T (1702). The History of the Works of the Learned. H.Rhodes. p. 498. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- Dabundo, Laura (2009). Encyclopedia of Romanticism (Routledge Revivals). Routledge. pp. 442–443. ISBN 978-1135232351. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- Daniel, Stephen H. "Toland's Semantic Pantheism," in John Toland's Christianity not Mysterious, Text, Associated Works and Critical Essays. Edited by Philip McGuinness, Alan Harrison, and Richard Kearney. Dublin, Ireland: The Lilliput Press, 1997.

- R.E. Sullivan, "John Toland and the Deist controversy: A Study in Adaptations", Harvard University Press, 1982, p. 193.

- Harrison, Paul. "Toland: The father of modern pantheism". Pantheist History. World Pantheist Movement. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- Toland, John, Pantheisticon, 1720; reprint of the 1751 edition, New York and London: Garland, 1976, p. 54.

- Paul Harrison, Elements of Pantheism, 1999.

- Honderich, Ted, The Oxford Companion to Philosophy, Oxford University Press, 1995, p. 641: "First used by John Toland in 1705, the term 'pantheist' designates one who holds both that everything there is constitutes a unity and that this unity is divine."

- Thompson, Ann, Bodies of Thought: Science, Religion, and the Soul in the Early Enlightenment, Oxford University Press, 2008, p. 133, ISBN 9780199236190.

- Worman cites Waterland, Works, viii, p. 81.

- Worman cites Wegscheider, Institutiones theologicae dogmaticae, p. 250.

- Giovanni, di; Livieri, Paolo (6 December 2001). "Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- Dahlstrom (3 December 2002). "Moses Mendelssohn". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- Goetschel, Willi (2004). Spinoza's Modernity: Mendelssohn, Lessing, and Heine. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0299190804.

- Pope BI. Pius IX (9 June 1862). "Syllabus of Errors 1.1". Papal Encyclicals Online. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- Herndon, William (4 February 1866). "Sold – Herndon's Revelations on Lincoln's Religion" (Excerpt and review). Raab Collection. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- Adams, Guy (17 April 2011). "'Pantheist' Lincoln would be unelectable today". The Independent. Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- Literary Remains of the Late Professor Theodore Goldstucker, W. H. Allen, 1879. p. 32.

- Thilly, Frank (2003) [1908]. "Pantheism". In Hastings, James (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics, Part 18. Kessinger Publishing. p. 614. ISBN 9780766136953.

- Armstrong, AH (1967). The Cambridge History of Later Greek and Early Medieval Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 57, 60, 161, 186, 222. ISBN 978052104-0549.

- McLynn, Frank (2010). Marcus Aurelius: A Life. Da Capo Press. p. 232. ISBN 9780306819162.

- "About Realism". The Realist Society of Canada. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- Jammer (2011), Einstein and Religion: Physics and Theology, Princeton University Press, p. 51; original at Einstein Archive, reel 33-275.

- "Belief in God a 'product of human weaknesses': Einstein letter". CBC News. 13 May 2008. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- "Richard Dawkins Foundation, Der Einstein-Gutkind Brief – Mit Transkript und Englischer Übersetzung". 31 May 2017.

- Einstein, Albert (2010). Ideas And Opinions. New York: Three Rivers Press. p. 262.

- Adler, Margot (1986). Drawing Down the Moon. Beacon Press.

- Sagan, Dorion, "Dazzle Gradually: Reflections on the Nature of Nature" 2007, p. 14.

- Caritas In Veritate, 7 July 2009.

- "43rd World Day of Peace 2010, If You Want to Cultivate Peace, Protect Creation | BENEDICT XVI". www.vatican.va. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- "New Mural in Vence: "Luminaries of Pantheism"". VenicePaparazzi. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- Rod, Perry. "About the Paradise Project". The Paradise Project. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- Wood, Harold (Summer 2017). "New Online Pantheism Community Seeks Common Ground". Pantheist Vision. 34 (2): 5.

- Levine, Michael (2020). "Pantheism". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Charles Hartshorne and William Reese, ed. (1953). Philosophers Speak of God. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 165–210.

- Goldsmith, Donald; Marcia Bartusiak (2006). E = Einstein: His Life, His Thought, and His Influence on Our Culture. New York: Stirling Publishing. p. 187. ISBN 9781402763199.

- F.C. Copleston, "Pantheism in Spinoza and the German Idealists," Philosophy 21, 1946, p. 48.

- Literary and Philosophical Society of Liverpool, "Proceedings of the Liverpool Literary & Philosophical Society, Volumes 43–44", 1889, p. 285.

- John Ferguson, "The Religions of the Roman Empire", Cornell University Press, 1970, p. 193.

- Isaacson, Walter (2007). Einstein: His Life and Universe. Simon and Schuster. p. 391. ISBN 9781416539322.

I am a determinist.

- Lindsay Jones, ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of Religion: Volume 10 (2nd ed.). USA: MacMillan. ISBN 978-0028657332.

- Dependence and Freedom: The Moral Thought of Horace Bushnell by David Wayne Haddorff Emerson's belief was "monistic determinism".

- Creatures of Prometheus: Gender and the Politics of Technology by Timothy Vance Kaufman-Osborn, Prometheus ((Writer)) "Things are in a saddle, and ride mankind."

- Emerson's position is "soft determinism" (a variant of determinism) .

- "The 'fate' Emerson identifies is an underlying determinism." (Fate is one of Emerson's essays) .

- Hegel was a determinist" (also called a combatibilist a.k.a. soft determinist). "Hegel and Marx are usually cited as the greatest proponents of historical determinism."

- Levine, Michael P. (August 1992). "Pantheism, substance and unity". International Journal for Philosophy of Religion. 32 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1007/bf01313557. JSTOR 40036697. S2CID 170517621.

- Moran, Dermot; Guiu, Adrian (2019), "John Scottus Eriugena", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2019 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 19 March 2020

-

- Theories of the will in the history of philosophy by Archibald Alexander p. 307 Schelling holds "...that the will is not determined but self-determined."

- The Dynamic Individualism of William James by James O. Pawelski p. 17 "[His] fight against determinism" "My first act of free will shall be to believe in free will."

- "Pantheism". The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. Columbia University Press. 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- Owen, H. P. (1971). Concepts of Deity. London: Macmillan. p. 67.

- Urmson 1991, p. 297.

- Schaffer, Jonathan. "Monism: The Priority of the Whole" (PDF). johnathanschaeffer.org. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- Schaffer, Jonathan (19 March 2007). "Monism". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2015 ed.).

- Brugger 1972.

- Mandik 2010, p. 76.

- Evangelical Dictionary of Theology, edited by Walter A. Elwell, p. 887.

- "Pantheists Around the World".

- "2011 National Household Survey: Data tables". Statistics Canada. 8 May 2013. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (26 October 2022). "Religion by visible minority and generation status: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations with parts". www150.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- Gilmour, Desmond A. (January 2006). "Changing Religions in the Republic of Ireland, 1991–2002". Irish Geography. 39 (2): 111–128. doi:10.1080/00750770609555871.

- "Census 2006: Volume 13 – Religion" (PDF). Dublin, Ireland: Central Statistics Office. 2007. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- "Statistical Tables" (PDF). cso.ie. p. 47. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- "Results of a Census of the Colony of New Zealand Taken for the Night of the 31st March 1901". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- "Results of a Census of the Colony of New Zealand Taken for the Night of the 29th April, 1906". Statistics New Zealand. 29 April 1906. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- 2006 New Zealand census.

- 2011 Australia Census

- 2001 Scotland Census

- "2011 Census: Religion". Census Office for National Statistics. 2011. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- "Census 2011: Religion – Full Detail: QS218NI – Northern Ireland". nisra.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- 2006 Uruguay Census

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (26 October 2022). "Religion by visible minority and generation status: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations with parts". www150.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- McDowell, Michael; Brown, Nathan Robert (2009). World Religions at Your Fingertips – Michael McDowell, Nathan Robert Brown – Google Books. Penguin. ISBN 9781592578467. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- Cooper, John W. (2006). The Other God of the Philosophers. Baker Academic.

- Levine 1994, p. 11.

- Craig, Edward, ed. (1998). "Genealogy to Iqbal". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. p. 100. ISBN 9780415073103.

- Johnston, Sean F. (2009). The History of Science: A Beginner's Guide. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-85168-681-0.

- Seager, William; Allen-Hermanson, Sean (23 May 2001). "Panpsychism". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2012 ed.).

- Haught, John F. (1990). What Is Religion?: An Introduction. Paulist Press. p. 19.

- Parrinder, EG (1970). "Monotheism and Pantheism in Africa". Journal of Religion in Africa. 3 (2): 81–88. doi:10.1163/157006670x00099. JSTOR 1594816.

- Levine 1994, p. 67.

- Harrison, Paul. "North American Indians: the spirituality of nature". World Pantheist Movement. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- Harrison, Paul. "The origins of Christian pantheism". Pantheist history. World Pantheists Movement. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- Fox, Michael W. "Christianity and Pantheism". Universal Pantheist Society. Archived from the original on 9 March 2001. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- Zaleha, Bernard. "Recovering Christian Pantheism as the Lost Gospel of Creation". Fund for Christian Ecology, Inc. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- Mungello, David E (1971). "Leibniz's Interpretation of Neo-Confucianism". Philosophy East and West. 21 (1): 3–22. doi:10.2307/1397760. JSTOR 1397760.

- Lan, Feng (2005). Ezra Pound and Confucianism: remaking humanism in the face of modernity. University of Toronto Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-8020-8941-0.

- Fowler 1997, p. 2.

- Fowler 2002, p. 15-32.

- Long 2011, p. 128.

- Singh, Nikky-Guninder Kaur (1992). "The Myth of the Founder: The Janamsākhīs and Sikh Tradition". History of Religions. 31 (4): 329–343. doi:10.1086/463291. S2CID 161226516.

- Ahluwalia, Jasbir Singh (March 1974). "Anti-Feudal Dialectic of Sikhism". Social Scientist. 2 (8): 22–26. doi:10.2307/3516312. JSTOR 3516312.

- Carpenter, Dennis D. (1996). "Emergent Nature Spirituality: An Examination of the Major Spiritual Contours of the Contemporary Pagan Worldview". In Lewis, James R., Magical Religion and Modern Witchcraft. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-2890-0. p. 50.

- "Home page". Universal Pantheist Society. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- World Pantheist Movement. "Naturalism and Religion: can there be a naturalistic & scientific spirituality?". Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- Stone, Jerome Arthur (2008). Religious Naturalism Today: The Rebirth of a Forgotten Alternative. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 10. ISBN 978-0791475379.

- Bron Raymond Taylor, "Dark Green Religion: Nature Spirituality and the Planetary Future", University of California Press, 2010, pp. 159–160.

Sources

- Fowler, Jeaneane D. (1997), Hinduism: Beliefs and Practices, Sussex Academic Press

- Fowler, Jeaneane D. (2002), Perspectives of Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Hinduism, Sussex Academic Press

- Levine, Michael (1994), Pantheism: A Non-Theistic Concept of Deity, Psychology Press, ISBN 9780415070645

- Long, Jeffrey D. (2011), Historical Dictionary of Hinduism, Scarecrow Press

- Urmson, James Opie (1991), The Concise Encyclopedia of Western Philosophy and Philosophers, Routledge

- Brugger, Walter, ed. (1972), Diccionario de Filosofía, Barcelona: Herder, art. dualismo, monismo, pluralismo

- Mandik, Pete (2010), Key Terms in Philosophy of Mind, Continuum International Publish.

Further reading

- Amryc, C. Pantheism: The Light and Hope of Modern Reason, 1898. online

- Harrison, Paul, Elements of Pantheism, Element Press, 1999. preview

- Hunt, John, Pantheism and Christianity, William Isbister Limited, 1884. online

- Levine, Michael, Pantheism: A Non-Theistic Concept of Deity, Psychology Press, 1994, ISBN 9780415070645

- Picton, James Allanson, Pantheism: Its story and significance, Archibald Constable & Co., 1905. online.

- Plumptre, Constance E., General Sketch of the History of Pantheism, Cambridge University Press, 2011 (reprint, originally published 1879), ISBN 9781108028028 online

- Russell, Sharman Apt, Standing in the Light: My Life as a Pantheist, Basic Books, 2008, ISBN 0465005179

- Urquhart, W. S. Pantheism and the Value of Life, 1919. online

External links

- Bollacher, Martin 2020: pantheism. In: Kirchhoff, T. (Hg.): Online Encyclopedia Philosophy of Nature. Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg

- Pantheism entry by Michael Levine (earlier article on pantheism in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

- Mander, William. "Pantheism". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- The Pantheist Index, pantheist-index.net

- An Introduction to Pantheism (wku.edu)

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- The Universal Pantheist Society (pantheist.net)

- The World Pantheist Movement (pantheism.net)

- Pantheism.community by The Paradise Project (pantheism.com)

- Pantheism and Judaism (chabad.org)

- On Whitehead's process pantheism : Michel Weber, Whitehead's Pancreativism. The Basics. Foreword by Nicholas Rescher, Frankfurt / Paris, Ontos Verlag, 2006.