Neverver language

Neverver (Nevwervwer), also known as Lingarak, is an Oceanic language. Neverver is spoken in Malampa Province, in central Malekula, Vanuatu. The names of the villages on Malekula Island where Neverver is spoken are Lingarakh and Limap.

| Neverver | |

|---|---|

| Lingarak | |

| Native to | Vanuatu |

| Region | Central Malekula |

Native speakers | 560 (2012)[1] |

| Dialects |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | lgk |

| Glottolog | ling1265 |

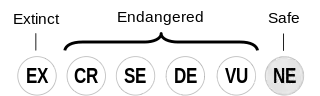

Neverver is not endangered according to the classification system of the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

Neverver is a threatened language, and native languages are protected and secured by the local government that is in charge. Sixty percent of the children are able to speak this language.[2] However, the dominant languages in the community, such as Bislama, English, and French are pushed to be used within these language communities.[3] Bislama is the most widely used language within this region. English and French are the two most distinguished languages within this region because they are connected with the schooling system. In the Malampa Province, English and French are the primary languages taught for education. English is used for business transactions within this region and helps generate revenue within the region.[2] This is due to the fact that before this province gained its independence in 1980 they were governed by the joint French-English colonial rule. Overall, there are only 550 native speakers of Neverver.

Neverver falls under the Oceanic branch of the Austronesian language family (based on comparison of cognates, morphology, phonology and other evidence markers), which is the second largest language family in the world.[4] There are two dialects of the Neverver language; Mindu and Wuli.[5]

Phonology

Consonants

Neverver contains a total of 27 consonant phonemes in five distinct places of articulation and six distinct manners of articulation.[1] A notable feature of Neverver is that some voiced consonants appear only in its prenasalized form.[1] Another feature of Neverver's consonants is that some have a contrastive geminate counterpart: /pː/, /tː/, /kː/, /mː/, /nː/, /lː/, /rː/, and /sː/.[1] The consonant phonemes are given in the table below using the International Phonemic Alphabet (IPA).

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasals | m | n | ŋ | ||

| Plosives/ Affricates |

plain | p | t | k | |

| prenasalized | ᵐb | ⁿd | ⁿdʒ | ᵑɡ | |

| Fricatives | β | s | ɣ | ||

| Trills | plain | r | |||

| prenasalized | ᵐᵇʙ | ⁿᵈr | |||

| Approximants | l | j | w | ||

Voiced obstruents, including the fricatives /β/ and /ɣ/, and the prenasalized trills /mbʙ/ and /ndr/ are devoiced in word-final position in rapid speech. Among younger speakers, the prenasalized plosives become simple nasals in word-final position.

The plosive /p/ becomes a voiceless trill [ʙ̥] before the vowel /u/.[6]

Vowels

Neverver contains a total of eight vowel phonemes, five regular vowels and three diphthongs. However, there is evidence that /y/ and /ø/ are contrastive among older speakers, bringing the total number of vowels to ten for some speakers.[1] The vowel phonemes are given in the table on the left IPA. A list of diphthongs are also provided in the table on the right along with examples.[1]

Syllable structure

Neverver allows for syllables with up to one consonant in the onset and in the coda, including syllables with only a nucleus. This means the structure of syllables is (C)V(C).[1] An example of the possible syllable structures is given in the table below where the corresponding syllables are in bold:[1]

| Template | Instantiation | English Translation |

|---|---|---|

| V | /ei/ | "he" |

| CV | /nau/ | "cane" |

| VC | /i.βu.ŋis.il/ | "he made smile" |

| CVC | /tox/ | "exist" |

Stress

Stress in Neverver is regular and not contrastive. It generally falls on the singular syllable of monosyllabic words and on the penultimate syllable of multisyllabic words. In compounds, each stem is treated separately so stress is assigned to each following the general stress pattern.[1] Examples of the assignment of stress in common words are given in the table below.[1]

| Example | English Translation |

|---|---|

| ['naus] | "rain" |

| ['naɣ.len] | "water" |

| [ni.'te.rix] | "child" |

Verbs follow a stress pattern that is different from the general stress pattern. In verbs, stress falls on the first syllable of the verb stem, disregarding the obligatory prefix; however, in imperative statements, stress is placed on the subject/mood prefix and on the first syllable of the verb stem. During reduplication, primary stress is assigned to the first instance of the reduplication.[1] Examples of the assignment of stress in verbs, instances of reduplication, and imperative statements are given in the table below.[1]

| Example | English Translation |

|---|---|

| [is.'ɣam] | "one" |

| [im.'ʙu.lem] | "(s)he will come" |

| [na.mbit.'liŋ.liŋ] | "we will leave (her)" |

| [nit.'mal.ma.lu] | "we dispersed" |

| ['kam.'tuɸ] | "go away!" |

| ['kum.'ʙu.lem] | "come!" |

Pronoun and person markers

Neverver uses different pronominal and nominal forms. There are three main noun classes: common, personal, and local nouns. There is also another fourth pronominal-noun category which blends features of the Neverver pronominal system with properties of the three major noun classes. There are three pronoun paradigms in Neverver: independent personal pronouns, possessive determiners, and possessive pronouns. Like most Austronesian languages, in Neverver the inclusive/exclusive distinction only applies to the 1st person plural category. Personal nouns in Neverver include personal proper names as well as personal kin terms.

Independent personal pronouns

Independent personal pronouns encode basic person and number contrasts. This includes the optionally articulated i-, which can indicate either a subject or object. Although this initial i- is optional with the pronouns, it is obligatory with the personal interrogative. For example, i-sikh means 'who'. Independent personal pronouns usually refer to animate entities, unless in some particular circumstances such as reflexive constructions. Below is a table showing the independent pronoun paradigm:[7]

| Singular | Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | Inclusive | (i-)na | (i-)git |

| Exclusive | (i-)nam ~ (gu)mam | ||

| 2nd person | (i-)okh | (i-)gam | |

| 3rd person | ei | adr | |

Subject/mood

Furthermore, all subjects, both nominal and pronominal, are cross-referenced with a subject/mood prefix which is attached to the verb stem in realis tense. These subject/mood prefixes differ from independent personal pronouns because there is a further dual distinction in addition to the singular and plural distinction. Subject/mood prefixes are also obligatory in all verbal constructions, unlike independent pronouns. Below is a table showing the subject/mood paradigm:[8]

| Singular | Dual | Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | Inclusive | ni- | nir(i)- | nit(i)- |

| Exclusive | nar(i)- | nat(i)- | ||

| 2nd person | ku- | kar(i)- | kat(i)- | |

| 3rd person | i- | ar(i)- | at(i)- | |

The table shows that the 3rd person form is irregular.

Gender

In Neverver there are gendered pronominal nouns, with vinang expressing a female and mang expressing a male. These can be obligatory modified with a demonstrative or a relative clause. Gender can also be expressed using third person singular pronouns. In Neverver, when there are two human participants involved of different genders, one is expressed with a gender-coded form and the other can be coded with an optional gender-neutral ei. The gender-coded form to express a female participant as the grammatical subject of the first clause, is encoded in the subject/mood prefix i-. If the male becomes the grammatical subject in the next clause, this is distinguished with the male pronominal-noun mang. For example:[9]

I-vlem,

3:REAL:SG-come

mang

man:ANA

i-lav

3:REAL:SG-get

ei

3SG

'She came and the man married her.' [NVKS10.112]

In the above example there is a male and female participant involved. The subject/mood prefix i- encodes that the female is the subject of the first clause. When the subject shifts to the male, the pronominal-noun mang is used to show this shift. To show that the female has become the object again, the 3rd person pronoun ei expresses this.

Possessive determiners

Prefixes derive possessive determiners in Neverver. Most of these begin with the possessive prefix t-. In Neverver, possessive determiners refer exclusively to human possessors, and a different construction is used to express non-human possessors. Below is a table showing the possessive determiners paradigm:[9]

| Singular | Non-singular | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | Inclusive | (t-)na | (t-)git |

| Exclusive | (t-)nam ~ (t-)mam | ||

| 2nd person | (t-)ox | (t-)gam | |

| 3rd person | titi ~ ei | titi-dr ~ adr | |

3. Possessive pronouns

Prefixes also derive possessive pronouns in Neverver. Possessive pronouns are made up of a nominalising prefix at- and the possessive prefix t-, which are both attached to the base pronominal morpheme (the independent pronoun). Furthermore, when the nominalising prefix is attached, the possessive pronoun can become the head of the noun phrase by itself. Below is a table showing the possessive pronoun paradigm:[10]

| Singular | Non-singular | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | Inclusive | at-t-na | at-t-git |

| Exclusive | at-t-nam | ||

| 2nd person | at-t-okh | at-t-gam | |

| 3rd person | at-titi | at-titi-dr | |

As the table shows, the 3rd person form uses the suppleted titi morpheme rather than the independent personal pronoun form. For example, at-t-na means 'mine' and at-titi-dr means 'theirs'.

Personal nouns

In Neverver, personal nouns are one of the three main noun classes, along with common nouns and local nouns. These personal nouns can include personal proper names and personal kin terms. Many of the women's personal proper names are traditionally marked with the morphemes le- or li; however, there is no morpheme associated with men's traditional personal proper names. Neverver also has a small set of kin terms that can express family relations as well as other name avoidance strategies.[11]

Syntax

Basic word order

The basic word order of Neverver is SVO, including intransitive, transitive, and ditransitive verbs.[1] Examples of sentences with intransitive, transitive, and ditransitive verbs are given below.[1]

Subject

Nibisbokh

rat

ang

ANA

Verb (Intransitive)

i-dum

3:REAL:SG-run

"The rat ran."

Subject

Nibisbokh

rat

ang

ANA

Verb (Transitive)

i-te

3:REAL:SG-cut

Primary Object

noron

leaf

nidaro.

taro

"The rat cut taro leaves."

Subject

Niterikh

child

Verb (Ditransitive)

i-sus-ikh

3:REAL:SG-ask-APPL

Primary Object

nida

mother

titi

3:POSS:SG

Secondary Object

ni-kkan-ian

NPR-eat-NSF

"The child asked his mother for food."

Possession

In Neverver, there are a numerous ways to describe possession. The correlation between an object and what matter it is made up of can make a difference in describing possession.[2] There are seven main types of possession in the language of Neverver. This includes:[12]

- Human Possession

- Inherent possessions without nominal modifier

- Associative possession with nominal modifier

- Relative clause without nominal modifier

- Relative clause with nominal modifier

- Number relative clause without nominal modifier

- Number relative clause with nominal modifier

Some examples of possession from Barbour are:[2]

- Human possession: nida (mother) t-na "my mother"

- Associative possession with nominal modifier: wido (window) an (nmod) nakhmal (house) ang (the) "The window of the house"

- Number relative clause with nominal modifier: nimokhmokh-tro (female old) an (nmod) i-ru (two) ang (the) "the two old women/wives"

Reduplication

Reduplication of words occur in the language of Neverver. They occur in conjunction with verbs in this language. Words are reduplicated by reproducing and repeating the entire word or partially of it.[4] For example, the word 'tukh' of Neverver means strike, when duplicated to 'tukh tukh' it produces the word for beat.[2]

Reduplication Constraint One is used within Neverver. This is when a word's prefix being reduplicated follows the constant-verb format.[2] The table below shows examples of this:[13]

| Simple Stem | Reduplicated Stem |

|---|---|

| CV te 'hit' |

CV-CV tete 'fight' |

| CVC tas 'scratch' |

CVC-CVC tas-tas 'sharpen' |

| CVCV malu 'leave' |

CVC-CVCV mal-malu 'disperse' |

| CCV tnga 'search' |

CV-CCV ta-tnga 'search' (duration) |

| CCVC sber 'reach' |

CV-CCVC se-sber 'touch' |

The most useful process of Reduplication in Neverver is to acquire a stative verb from a verb encoding action. Some examples of this can be seen in the table below.[14]

| Base | Reduplicant |

|---|---|

| tur 'stand up' | turtur 'stand' |

| ngot 'break' | ngotngot 'be broken' |

| jing 'lie down' | jingjing 'be lying down' |

There are irregular reduplications within Neverver that do not follow the constant-verb format. According to Julie Barbour, the word vlem, which means "come", does not follow this format.[15] It would be implied that the reduplication of this word would ve-vlem. Julie Barbour uses the example sentence "Ari vle-vle-vle-vlem" which translates into "They came closer and closer."[15]

Negation

Negation is a grammatical construction that semantically expresses a contradiction to a part of or an entire sentence.[16] In Lingarak, negatives typically contradict verb constructions.

Forming negations

Verb clauses in Lingarak are negated using the negative particle si.[17] This negative particle always occurs after the verb. Thus, the particle is typically called a post-verbal negative particle. It can be used to negate the following constructions:

- Declarative clause - clauses that are typically used to express statements.[18]

- Imperative clauses - clauses that are typically used to give commands.[19] This can be observed in example 15 below.

- Realis mood - a mood of language, where the proposition is strongly asserted to be true and apparent, and can be readily backed up with evidence.[20] Realis verb forms typically involve the past tense.

- Irrealis mood - a mood of language, where the proposition is weakly asserted to be true, and not readily backed up with evidence. Irrealis verb forms typically involve certain modals.

In example 1 below, a declarative clause in the realis mood has been negated.[21] The verb i-vu meaning 'go' in third person singular realis mood is negated using the post-verbal negative particle si.

Be

but

mama

father

i-vu

3:REAL:SG-go

si.

NEG

But the father didn't go

Similar to example 1 above, the post-verbal negative particle si is also used to negate the first person singular nibi-kkan meaning 'eat' in example 2 below.[21] However, the following should be noted:

- The post-verbal negative particle si directly follows the verbal construction that it is negating. In this case nibi-kkan. This is important in this example because there are two verbs involved. Since si directly follows nibi-kkan, it only negates nibi-kkan and not i-ver.

- It is also important to notice that the verb that is being negated nibi-kkan, directly precedes si, and that si directly precedes the reduced exclamatory particle in. Any part of a sentence that is being negated and occurs after the negated verb construction will occur after si in the negated construction. There are however certain exceptions for this as shown in examples 6 to 9 where si affixes to form new aspect markers, and also in examples 10 to 13 where si occurs with serial verb constructions.

Vinang

woman:ANA

i-ver

3:REAL:SG-say

"Na

1SG

nibi-kkan

1:IRR:SG-eat

si

NEG

in!"

EXCLAM

The woman said, "I won't eat!"

Example 3 below shows another example of negation using the post-verbal negative particle si.[21] However, in this example it is important to observe that any words (that can take a mood) after si in example 3 are written in the irrealis mood. This is another characteristic of negation in Lingarak. When something in the realis mood is negated in Lingarak, then elements following the si particle will be written in irrealis mood.[21]

Ei

3SG

i-khan

3:REAL:SG-eat

si

NEG

navuj

banana

ibi-skhan.

3:IRR:SG-one.

He didn't eat a banana

Existential negation

In Lingarak, verb constructions that express the meaning of existence, also known as existential constructions, are treated like other common verbs when being negated.[17] Thus, to negate the verb tokh in Lingarak which means ‘to exist’, only a si particle is required to follow it as shown in example 4 below.[21]

Nakhabb

fire

vangvang

be alight

i-takh

3:REAL:SG-exist

si.

NEG

There was no fire

This is atypical of Oceanic languages since Oceanic languages typically have special negative existential verbs as shown below in example 5.[22] This example is in Tokelauan which is spoken in Polynesia. In contrast to the Lingarak, Tokelauan uses a verb in the negative form for 'exist' instead of a post-verbal negative particle.

Kua

PERF

hēai

NEG:exist

he

INDEF

huka.

sugar

There isn't any more sugar

Affixing si with aspect markers

In Lingarak, the aspect of continuity is expressed with mo. When a verb that is occurring continuously is negated, the si particle is used as an affix and is connected to the end of mo. Thus, creating a new particle mosi which means ‘no longer’.[17] This is demonstrated in example 6 below.[17] Similar to examples 1 and 2 above, the negative particle si occurs after the verbal construction. (In this case Nimt-uv-uv, meaning 'go'.) In order to express the continuous aspect of the verb Nimt-uv-uv, si is affixed into the end of the aspect marker mo to form mosi. This now gives the negation the meaning of 'no longer' as shown in the free translation of example 6.

Nimt-uv-uv

1PL:INCL:IRR-REDUP-go

mo-si

CONT-NEG

il

CAUS

naut

place

i-met

3SG:REAL-dark

We can't go anymore because it's dark

It should also be noted that the affixes mo- and -si in example 6 above are interchangeable in terms of affix order. This is demonstrated in example 7 below.[21] In contrast to mosi in example 6 above, si precedes the continuous aspect marker mo to form the continuous negation particle simo.[17] Similar to the particle mosi in example 6, simo also has the meaning of 'no longer' as shown in the free translation of example 7.

Git

1NSG:INCL

nimt-uv-uv

1PL:INCL:IRR:REDUP-go

si-mo

NEG-CONT

We can't go anymore

Similar to the aspect of continuation, the aspect of ‘not yet’ can also be expressed by the particle vas which is short for vasi.[21] This particle is formed by reducing the affixation of si onto the particle va. Unlike mo, va in Lingarak is not a free morpheme. Thus, it is inseparable from si. Example 8 presented below demonstrates an instances of vasi.[21]

Nabbun

smell

nitan-jakh

thing:DEF-be here

nit-rongil

1PL:INCL:REAL:know

vasi

not yet

'The smell of this thing, we don't know it yet.'

A sentence using the reduced form of vasi which is vas as discussed above, is presented in example 9 below.[21]

Ar

3NSG

at-rongil

3PL:REAL-REDUP-leave

vas

not yet

deb

CONT

nemaki

denizen

Litslits

Litzlitz

They still don't know the people of Litzlitz yet

Negating serial verb constructions

In Lingarak, verbs can be strung together to form a single complex nucleus. This is process of compounding two verbs can be analysed as an instance of serialisation.[23] These instances of verb constructions are typically referred to as serialised verb constructions and also typically behave like a single verb. In this way, they can only have one subject argument, and one si particle for negation. An example of negating one of these serialised verbs is demonstrated in example 10 below.[17]

Na

1SG

ni-ver

1:SG:REAL-say

te

COMP

ei

3SG

ib-lav-bir

3SG:IRR-get-break/win

si

NEG

I said he didn't return it

As seen in example 10 above, the serialised verb construction ib-lav-bir, is negated with the post verbal particle si like all other typical scenarios of verb clause negation in Lingarak.[24] This is because this serialised verb construction behaves like a single verb. However, the placement of the si particle begins to change when the second verb in the construction begins to play a more prepositional role (rather than verbal) as discussed below.

The form delivs in Lingarak means 'go around'. However, this verb never occurs independently, but instead will serialise on the end of other verbs to form serial verb constructions. The serial constructions are presented in the table below. However, it is important to note that these serialisations only occur for verbs that have meaning of motion or posture.

| Verb of motion or posture | English equivalent of verb | Serialised verb construction | English equivalent of serialised verb construction |

|---|---|---|---|

| sav | 'dance' | sav delvis | 'dance around' |

| dum | 'run' | dum delvis | 'run around' |

| vavu | 'walk' | vavu delvis | 'walk around' |

| vor | 'sit' | vor delvis | 'sit around' |

Despite the prepositional like meaning of delvis, when serialised with other verbs, the serialised verb construction behaves like ib-lav-bir when being negated by the post-verbal negative particle si since it is inherently a verb meaning 'go around'. This behaviour is illustrated in example 11 below.[24]

sav

dance

delvis

around

si

NEG

In addition to delvis, the form sur in Lingarak means 'near', 'along', in some other cases it also means 'by'. When compounded with verbs to create a compound verb construction, the placement of si begins to vary when negating these compounded constructions. Like sav delvis in example 11, example 12 is also negated using a post-verbal negative particle after a word with a prepositional like meaning sur.[24]

At-savsav-sur

3PL:REAL-climb-along

si

NEG

nakha

tree

They didn't climb along the tree

In contrast to example 12 above, example 13 below places the negative particle between i-vlem 'come' and sur. Thus, as stated above, si has broken a compound verb construction. The placement of the si particle has changed when negating verb constructions which have sur in the position of the second verb of a serialised verb construction. Thus as discussed above, the placement of si begins to change when the second verb in the construction begins to play a more prepositional role. It is possible that this inconsistent nature of sur is occurring because sur is currently undergoing re-analysis from verb to preposition.[24]

Nimkhut

man

i-vlem

3SG:REAL-come

si

NEG

sur

near

nesal

road

The man didn’t come near the road

Negative verbs

There is also a repertoire of negative verbs in Lingarak. These are presented in the table below.[21]

| Positive | Negative | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| rongrok | 'want' | rosikh | 'not want' |

| khita | 'like/ love' | sre | 'dislike' |

| dadikh | 'be sufficient' | varikh | 'be insufficient' |

| (rongil) | 'know' | melmelikh | 'know nothing about' |

| gang | 'be like that' | skhen | 'be not so' |

These negative verbs are used like other verbs in Lingarak to express negative meaning and do not require si for negation of the negative counterparts are used. This can be shown in example 14 below.[21]

Kon

corn

le-lleng

REDUP-hang.down

i-skhen

3SG:REAL-not.so

ing

EXCLAM

It's not droopy corn

Forming prohibitions

When the post-verbal negative particle si is used alongside reduplication, negative imperatives and prohibitions can be formed. This is demonstrated in example 15 below.[25]

No,

no

ar-ver-ver

IMP:REAL-REDUP-say

si!

NEG

No, don't say that!

Expressing inability using mosi

The inability to perform an action can also be expressed by using mosi to negate action.[25] This is illustrated in example 16 below. In example 16, the function of mosi is expresses the 'loss of an ability' to perform an action.

Ga

then

i-yel-yel

3SG:REAL-REDUP-scoop-out

mo

CONT

si

NEG

i-vlem

3SG:REAL-come

aiem

home

Then she couldn't scoop out coconuts anymore and she came home

Negative condition

Negative 'if' conditions can be constructed using the post-verbal negative particle si in conjunction with reduplication[25] and besi (meaning 'if) as shown in example 17 below.

Besi

if

man-jakh

man-be.here

adr

PL

abit-ve-ve

3PL:IRR-REDUP-do

si

NEG

im-gang

3SG:IRR-like.so

If only these men hadn’t done it like that

Numbering System

Numbers one through nine follow a quinary pattern. It can either possess realis or irrealis mood and polarity of a main clause.

Below is a table showing the numerals, one through nine. A key characteristic of Neververs numbering system is associated with definiteness.[26]

| Realis | Irrealis | Number |

|---|---|---|

| i-skham | ibi-skham | one |

| i-ru | ib-ru | two |

| i-tl | ibi-tl | three |

| i-vas | im-bbwas | four |

| i-lim | ib-lim | five |

| i-jo-s | im-jo-s | six |

| i-jo-ru | im-jo-ru | seven |

| i-jo-tl | im-jo-tl | eight |

| i-jo-vas | im-jo-vas | nine |

Numbers in the form of ten or greater take on the form of a noun rather than a verb, as shown in the table below:[27]

| Number | Name |

|---|---|

| 10^1 (Ten) | nangavul |

| 10^2 (Hundred) | nagat |

| 10^3 (Thousand) | netar |

| 10^4 (Ten Thousand) | namul |

Clear cut numbers greater than ten contain the term 'nangavul nidruman':[28]

| Name | Number |

|---|---|

| nanguavul nidruman i-skham | eleven |

| nanguavul nidruman i-ru | twelve |

| nanguavul nidruman i-tl | thirteen |

| nanguavul nidruman i-vas | fourteetn |

| nanguavul nidruman i-lim | fifteen |

| nanguavul nidruman i-jo-s | sixteen |

| nanguavul nidruman i-jo-ru | seventeen |

| nanguavul nidruman i-jo-tl | eighteen |

| nanguavul nidruman i-jo-vas | nineteen |

| nanguavul i-ru | twenty |

| nanguavul i-ru nidruman i-skham | twenty one |

| nagat i-shkam nanguavul i-ru nidruman i-vas | one hundred and twenty four |

References

- Barbour 2012

- Barbour 2012.

- "Did you know Neverver is vulnerable?". Endangered Languages. Retrieved 2016-09-16.

- Sato, Hiroko; Terrell, Jacob (eds.). Language in Hawai'i and the Pacific.

- Neverver language at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- Barbour 2012, pp. 24–25.

- Barbour 2012, p. 72.

- Barbour 2012, p. 73.

- Barbour 2012, p. 75.

- Barbour 2012, p. 76.

- Barbour 2012, pp. 87–90.

- Barbour 2012, pp. 132–133.

- Barbour 2012, p. 230.

- Barbour 2012, p. 244.

- Barbour 2012, p. 232.

- Crystal 2009, pp. 323, 324

- Barbour 2012, p. 279

- Crystal 2009, p. 130

- Crystal 2009, p. 237

- Crystal 2009, pp. 402, 403

- Barbour 2012, pp. 280–282

- Hovdhaugen, Even (2000). Negation in Oceanic Languages: Typological Studies. Lincom Europa. ISBN 3895866024. OCLC 963109055.

- Margetts, Anna (1999), Valence and Transitivity in Saliba, an Oceanic Language of Papua New Guinea, Katholieke Universiteit Nijmegen, OCLC 812759222

- Barbour 2012, pp. 316, 321–324

- Barbour 2012, pp. 257, 258

- Barbour 2012, p. 157.

- Barbour 2012, p. 158.

- Barbour 2012, p. 159.