History of the Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946)

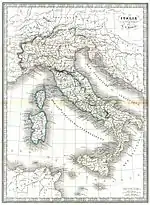

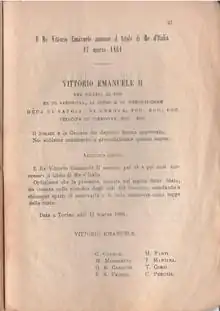

This article covers the history of Italy as a monarchy and in the World Wars. The Kingdom of Italy (Italian: Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia was proclaimed King of Italy, until 2 June 1946, when civil discontent led to an institutional referendum to abandon the monarchy and form the modern Italian Republic. The state resulted from a decades-long process, the Risorgimento, of consolidating the different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single state. That process was influenced by the Savoy-led Kingdom of Sardinia, which can be considered Italy's legal predecessor state.

| History of Italy |

|---|

|

|

|

In 1866, Italy declared war on Austria in alliance with Prussia and received the region of Veneto following their victory. Italian troops entered Rome in 1870, ending more than one thousand years of Papal temporal power. Italy entered into a Triple Alliance with the German Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1882, following strong disagreements with France about their respective colonial expansions. Although relations with Berlin became very friendly, the alliance with Vienna remained purely formal, due in part to Italy's desire to acquire Trentino and Trieste from Austria-Hungary. As a result, Italy accepted the British invitation to join the Allied Powers during World War I, as the western powers promised territorial compensation (at the expense of Austria-Hungary) for participation that was more generous than Vienna's offer in exchange for Italian neutrality. Victory in the war gave Italy a permanent seat in the Council of the League of Nations.

In 1922, Benito Mussolini became prime minister of Italy, ushering in an era of National Fascist Party government known as "Fascist Italy". The Italian Fascists imposed totalitarian rule and crushed the political and intellectual opposition while promoting economic modernization, traditional social values, and a rapprochement with the Roman Catholic Church through the Lateran Treaties which created the Vatican City as a rump sovereign replacement for the Papal States. In the late 1930s, the Fascist government began a more aggressive foreign policy. This included war against Ethiopia, launched from Italian Eritrea and Italian Somaliland, which resulted in its annexation;[1] confrontations with the League of Nations, leading to sanctions; growing economic autarky; and the signing of the Pact of Steel.

Fascist Italy became a leading member of the Axis powers in World War II. By 1943, the German-Italian defeat on multiple fronts and the subsequent Allied landings in Sicily led to the fall of the Fascist regime. Mussolini was placed under arrest by order of the King Victor Emmanuel III. The new government signed an armistice with the Allies on September 1943. German forces occupied northern and central Italy, setting up the Italian Social Republic, a collaborationist puppet state still led by Mussolini and his Fascist loyalists. As a consequence, the country descended into civil war, with the Italian Co-belligerent Army and the resistance movement contending with the Social Republic's forces and its German allies.

Shortly after the war and the country's liberation, civil discontent led to the institutional referendum on whether Italy would remain a monarchy or become a republic. Italians decided to abandon the monarchy and form the Italian Republic, the present-day Italian state.

Italian unification (1814–1870)

The Risorgimento was the political and social process that unified different states of the Italian peninsula into the single nation of Italy.

It is difficult to pin down exact dates for the beginning and end of Italian reunification, but most scholars agree that it began with the end of Napoleonic rule and the Congress of Vienna in 1815, and approximately ended with the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, though the last "città irredente" did not join the Kingdom of Italy until the Italian victory in World War I.

As Napoleon's reign began to fail, other national monarchs he had installed tried to keep their thrones by feeding those nationalistic sentiments, setting the stage for the revolutions to come. Among these monarchs were the viceroy of Italy, Eugène de Beauharnais, who tried to get Austrian approval for his succession to the Kingdom of Italy, and Joachim Murat, who called for Italian patriots' help for the unification of Italy under his rule.[2] Following the defeat of Napoleonic France, the Congress of Vienna (1815) was convened to redraw the European continent. In Italy, the Congress restored the pre-Napoleonic patchwork of independent governments, either directly ruled or strongly influenced by the prevailing European powers, particularly Austria.

.jpg.webp)

In 1820, Spaniards successfully revolted over disputes about their Constitution, which influenced the development of a similar movement in Italy. Inspired by the Spaniards (who, in 1812, had created their constitution), a regiment in the army of the Kingdom of Two Sicilies, commanded by Guglielmo Pepe, a Carbonaro (member of the secret republican organization),[5] mutinied, conquering the peninsular part of Two Sicilies. The king, Ferdinand I, agreed to enact a new constitution. The revolutionaries, though, failed to court popular support and fell to Austrian troops of the Holy Alliance. Ferdinand abolished the constitution and began systematically persecuting known revolutionaries. Many supporters of revolution in Sicily, including the scholar Michele Amari, were forced into exile during the decades that followed.[6]

The leader of the 1821 revolutionary movement in Piedmont was Santorre di Santarosa, who wanted to remove the Austrians and unify Italy under the House of Savoy. The Piedmont revolt started in Alessandria, where troops adopted the green, white, and red tricolore of the Cisalpine Republic. The king's regent, prince Charles Albert, acting while the king Charles Felix was away, approved a new constitution to appease the revolutionaries, but when the king returned he disavowed the constitution and requested assistance from the Holy Alliance. Di Santarosa's troops were defeated, and the would-be Piedmontese revolutionary fled to Paris.[7]

At the time, the struggle for Italian unification was perceived to be waged primarily against the Austrian Empire and the Habsburgs, since they directly controlled the predominantly Italian-speaking northeastern part of present-day Italy and were the single most powerful force against unification. The Austrian Empire vigorously repressed nationalist sentiment growing on the Italian peninsula, as well as in the other parts of Habsburg domains. Austrian Chancellor Franz Metternich, an influential diplomat at the Congress of Vienna, stated that the word Italy was nothing more than "a geographic expression."[8]

Artistic and literary sentiment also turned towards nationalism; and perhaps the most famous of proto-nationalist works was Alessandro Manzoni's I Promessi Sposi (The Betrothed). Some read this novel as a thinly veiled allegorical critique of Austrian rule. The novel was published in 1827 and extensively revised in the following years. The 1840 version of I Promessi Sposi used a standardized version of the Tuscan dialect, a conscious effort by the author to provide a language and force people to learn it.

Those in favour of unification also faced opposition from the Holy See, particularly after failed attempts to broker a confederation with the Papal States, which would have left the Papacy with some measure of autonomy over the region. The pope at the time, Pius IX, feared that giving up power in the region could mean the persecution of Italian Catholics.[9]

Even among those who wanted to see the peninsula unified into one country, different groups could not agree on what form a unified state would take. Vincenzo Gioberti, a Piedmontese priest, had suggested a confederation of Italian states under rulership of the Pope. His book, Of the Moral and Civil Primacy of the Italians, was published in 1843 and created a link between the Papacy and the Risorgimento. Many leading revolutionaries wanted a republic, but eventually it was a king and his chief minister who had the power to unite the Italian states as a monarchy.

One of the most influential revolutionary groups was the Carbonari (charcoal-burners), a secret organization formed in southern Italy early in the 19th century. Inspired by the principles of the French Revolution, its members were mainly drawn from the middle class and intellectuals. After the Congress of Vienna divided the Italian peninsula among the European powers, the Carbonari movement spread into the Papal States, the Kingdom of Sardinia, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, the Duchy of Modena and the Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia.

The revolutionaries were so feared that the reigning authorities passed an ordinance condemning to death anyone who attended a Carbonari meeting. The society, however, continued to exist and was at the root of many of the political disturbances in Italy from 1820 until after unification. The Carbonari condemned Napoleon III to death for failing to unite Italy, and the group almost succeeded in assassinating him in 1858. Many leaders of the unification movement were at one time members of this organization. (Note: Napoleon III, as a young man, fought on the side of the 'Carbonari'.)

In this context, in 1847, the first public performance of the song Il Canto degli Italiani, the Italian national anthem since 1946, took place.[10][11] Il Canto degli Italiani, written by Goffredo Mameli set to music by Michele Novaro, is also known as the Inno di Mameli, after the author of the lyrics, or Fratelli d'Italia, from its opening line.

Two prominent radical figures in the unification movement were Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi. The more conservative constitutional monarchic figures included the Count of Cavour and Victor Emmanuel II, who would later become the first king of a united Italy.

Mazzini's activity in revolutionary movements caused him to be imprisoned soon after he joined. While in prison, he concluded that Italy could – and therefore should – be unified and formulated his program for establishing a free, independent, and republican nation with Rome as its capital. After Mazzini's release in 1831, he went to Marseille, where he organized a new political society called La Giovine Italia (Young Italy). The new society, whose motto was "God and the People," sought the unification of Italy.

The creation of the Kingdom of Italy was the result of concerted efforts by Italian nationalists and monarchists loyal to the House of Savoy to establish a united kingdom encompassing the entire Italian Peninsula.

The Kingdom of Sardinia industrialized from 1830 onward. A constitution, the Statuto Albertino was enacted in the year of revolutions, 1848, under liberal pressure. Under the same pressure, the First Italian War of Independence was declared on Austria. After initial success the war took a turn for the worse and the Kingdom of Sardinia lost.

Garibaldi, a native of Nice (then part of the Kingdom of Sardinia), participated in an uprising in Piedmont in 1834, was sentenced to death, and escaped to South America. He spent fourteen years there, taking part in several wars, and returned to Italy in 1848.

After the Revolutions of 1848, the apparent leader of the Italian unification movement was Italian nationalist Giuseppe Garibaldi. He was popular amongst southern Italians.[12] Garibaldi led the Italian republican drive for unification in southern Italy, but the northern Italian monarchy of the House of Savoy in the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia whose government was led by Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, also had the ambition of establishing a united Italian state. Although the kingdom had no physical connection to Rome (deemed the natural capital of Italy), the kingdom had successfully challenged Austria in the Second Italian War of Independence, liberating Lombardy–Venetia from Austrian rule. On the basis of the Plombières Agreement, the Kingdom of Sardinia ceded Savoy and Nice to France, an event that caused the Niçard exodus, that was the emigration of a quarter of the Niçard Italians to Italy.[13] The kingdom also had established important alliances which helped it improve the possibility of Italian unification, such as Britain and France in the Crimean War.

Giuseppe Garibaldi was elected in 1871 in Nice at the National Assembly where he tried to promote the annexation of his hometown to the newborn Italian unitary state, but he was prevented from speaking.[14] Because of this denial, between 1871 and 1872 there were riots in Nice, promoted by the Garibaldini and called "Niçard Vespers",[15] which demanded the annexation of the city and its area to Italy.[16] Fifteen Nice people who participated in the rebellion were tried and sentenced.[17]

Unifying multiple bureaucracies

A major challenge for the prime ministers of the new Kingdom of Italy was integrating the political and administrative systems of the seven different major components into a unified set of policies. The different regions were proud of their historical patterns and could not easily be fitted into the Sardinian model. Cavour started planning but died before it was fully developed – indeed, the challenges of administration of various bureaucracies are thought to have hastened his death. The easiest challenge was to harmonize the administrative bureaucracies of Italy's regions. They practically all followed the Napoleonic precedent, so harmonization was straightforward. The second challenge was to develop a parliamentary system. Cavour and most liberals up and down the peninsula highly admired the British system, so it became the model for Italy to this day. Harmonizing the Army and Navy was much more complex, chiefly because the systems of recruiting soldiers and selecting and promoting officers were so different and needed to be grandfathered over decades. The disorganization helps explain why the Italian naval performance in the 1866 war was so abysmal. The military system was slowly integrated over several decades. Uniforming the several diverse education systems proved complicated as well. Shortly before his death, Cavour appointed Francesco De Sanctis as minister of education. De Sanctis was an eminent scholar from the University of Naples who proved an able and patient administrator. The addition of Veneto in 1866 and Rome in 1870 further complicated the challenges of bureaucratic coordination.[18]

Southern question and Italian diaspora

The transition was not smooth for the south (the "Mezzogiorno"). The path to unification and modernization created a divide between Northern and Southern Italy. People condemned the South for being "backwards" and barbaric, when in truth, compared to Northern Italy, "where there was backwardness, the lag, never excessive, was always more or less compensated by other elements".[19] Of course, there had to be some basis for singling out the South like Italy did. The entire region south of Naples was afflicted with numerous deep economic and social liabilities.[20] However, many of the South's political problems and its reputation of being "passive" or lazy (politically speaking) was due to the new government (that was born out of Italy's want for development) that alienated the South and prevented the people of the South from any say in important matters. However, on the other hand, transportation was difficult, soil fertility was low with extensive erosion, deforestation was severe, many businesses could stay open only because of high protective tariffs, large estates were often poorly managed, most peasants had only very small plots, and there was chronic unemployment and high crime rates.[21]

Cavour decided the basic problem was poor government, and believed that could be remedied by strict application of the Piedmonese legal system. The main result was an upsurge in brigandage, which turned into a bloody civil war that lasted almost ten years. The insurrection reached its peak mainly in Basilicata and northern Apulia, headed by the brigands Carmine Crocco and Michele Caruso.[22] With the end of the southern riots, there was a heavy outflow of millions of peasants in the Italian diaspora, especially to the United States and South America. Others relocated to the northern industrial cities such as Genoa, Milan and Turin, and sent money home.[21]

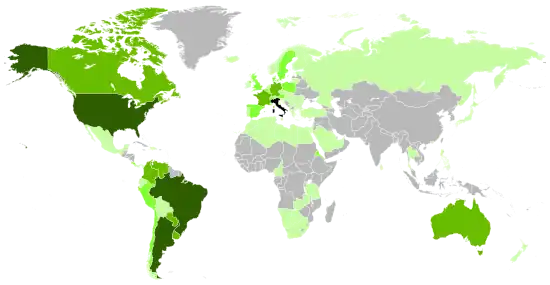

The first Italian diaspora began around 1880, two decades after the Unification of Italy, and ended in the 1920s to the early 1940s with the rise of Fascist Italy.[23] Poverty was the main reason for emigration, specifically the lack of land as mezzadria sharecropping flourished in Italy, especially in the South, and property became subdivided over generations. Especially in Southern Italy, conditions were harsh.[23] Until the 1860s to 1950s, most of Italy was a rural society with many small towns and cities and almost no modern industry in which land management practices, especially in the South and the Northeast, did not easily convince farmers to stay on the land and to work the soil.[24]

Another factor was related to the overpopulation of Southern Italy as a result of the improvements in socioeconomic conditions after Unification.[25] That created a demographic boom and forced the new generations to emigrate en masse in the late 19th century and the early 20th century, mostly to the Americas.[26] The new migration of capital created millions of unskilled jobs around the world and was responsible for the simultaneous mass migration of Italians searching for "work and bread" (Italian: pane e lavoro, pronounced [ˈpaːne e llaˈvoːro]).[27]

_07.jpg.webp)

The Unification of Italy broke down the feudal land system, which had survived in the south since the Middle Ages, especially where land had been the inalienable property of aristocrats, religious bodies or the king. The breakdown of feudalism, however, and redistribution of land did not necessarily lead to small farmers in the south winding up with land of their own or land they could work and make profit from. Many remained landless, and plots grew smaller and smaller and so less and less productive, as land was subdivided amongst heirs.[24]

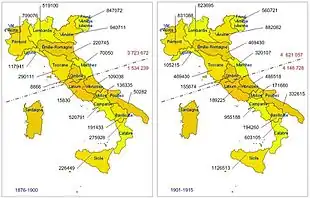

Between 1860 and World War I, 9 million Italians left permanently of a total of 16 million who emigrated, most travelling to North or South America.[28] The numbers may have even been higher; 14 million from 1876 to 1914, according to another study. Annual emigration averaged almost 220,000 in the period 1876 to 1900, and almost 650,000 from 1901 through 1915. Prior to 1900 the majority of Italian immigrants were from northern and central Italy. Two-thirds of the migrants who left Italy between 1870 and 1914 were men with traditional skills. Peasants were half of all migrants before 1896.[26]

The bond of the emigrants with their mother country continued to be very strong even after their departure. Many Italian emigrants made donations to the construction of the Altare della Patria (1885–1935), a part of the monument dedicated to King Victor Emmanuel II of Italy, and in memory of that, the inscription of the plaque on the two burning braziers perpetually at the Altare della Patria next to the tomb of the Italian Unknown Soldier, reads "Gli italiani all'estero alla Madre Patria" ("Italians abroad to the Motherland").[29] The allegorical meaning of the flames that burn perpetually is linked to their symbolism, which is centuries old, since it has its origins in classical antiquity, especially in the cult of the dead.[30] A fire that burns eternally symbolizes that the memory, in this case of the sacrifice of the Unknown Soldier and the bond of the country of origin, is perpetually alive in Italians, even in those who are far from their country, and will never fade.[30]

Liberal era (1861–1922)

_-_Cavour_cropped.jpg.webp)

Italy became a nation-state belatedly on 17 March 1861, when most of the states of the peninsula were united under king Victor Emmanuel II of the House of Savoy, which ruled over Piedmont. The architects of Italian unification were Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, the Chief Minister of Victor Emmanuel, and Giuseppe Garibaldi, a general and national hero. In 1866, Prussian Prime Minister Otto von Bismarck offered Victor Emmanuel II an alliance with the Kingdom of Prussia in the Austro-Prussian War. In exchange Prussia would allow Italy to annex Austrian-controlled Venice. King Emmanuel agreed to the alliance and the Third Italian War of Independence began. The victory against Austria allowed Italy to annex Venice. The one major obstacle to Italian unity remained Rome.

In 1870, France started the Franco-Prussian War and brought home its soldiers in Rome, where they had kept the pope in power. Italy marched in to take over the Papal State. Italian unification was completed, and the capital was moved from Florence to Rome.[31]

Some of the states that had been targeted for unification (terre irredente), Trentino-Alto Adige and Julian March, did not join the Kingdom of Italy until 1918 after Italy defeated Austria-Hungary in the First World War. For this reason, historians sometimes describe the unification period as continuing past 1871, including activities during the late 19th century and the First World War (1915–1918), and reaching completion only with the Armistice of Villa Giusti on 4 November 1918. This more expansive definition of the unification period is the one presented at the Central Museum of the Risorgimento at the Altare della Patria in Rome.[32][33]

In Northern Italy, industrialisation and modernisation began in the last part of the 19th century. The south, at the same time, was overpopulated, forcing millions of people to search for a better life abroad. It is estimated that around one million Italian people moved to other European countries such as France, Switzerland, Germany, Belgium and Luxembourg, and to the Americas.

Parliamentary democracy developed considerably in the 19th century. The Sardinian Statuto Albertino of 1848, extended to the whole Kingdom of Italy in 1861, provided for basic freedoms, but the electoral laws excluded the non-propertied and uneducated classes from voting.

Italy's political arena was sharply divided between broad camps of left and right which created frequent deadlock and attempts to preserve governments, which led to instances such as conservative Prime Minister Marco Minghetti enacting economic reforms to appease the opposition such as the nationalization of railways. In 1876, Minghetti lost power and was replaced by the Democrat Agostino Depretis, who began a period of political dominance in the 1880s, but continued attempts to appease the opposition to hold power.

Agostino Depretis

The results of the 1876 election resulted in only four representatives from the right being elected, allowing the government to be dominated by Agostino Depretis. Despotic and corrupt actions are believed to be the key means in which Depretis managed to keep support in southern Italy. Depretis put through authoritarian measures, such as banning public meetings, placing "dangerous" individuals in internal exile on remote penal islands across Italy, and adopting militarist policies. Depretis enacted controversial legislation for the time, such as abolishing arrest for debt, making elementary education free and compulsory while ending compulsory religious teaching in elementary schools.[34]

The first government of Depretis collapsed after his dismissal of his Interior Minister, and ended with his resignation in 1877. The second government of Depretis started in 1881. Depretis' goals included widening suffrage in 1882 and increasing the tax intake from Italians by expanding the minimum requirements of who could pay taxes and the creation of a new electoral system called which resulted in large numbers of inexperienced deputies in the Italian parliament.[35] In 1887, Depretis was finally pushed out of office after years of political decline.

Depretis was the founder and the main proponent of Trasformismo ("Transformism"), a method of making a flexible centrist coalition of government which isolated the extremes of the left and the right. The process was initiated in 1883, when he moved to the right and reshuffled his government to include Marco Minghetti's conservatives. This was a move Depretis had been considering for a while before 1883. The aim was to ensure a stable government that would avoid weakening the institutions by extreme shifts to the left or right. Depretis felt that a secure government could ensure calm in Italy.

At this time middle class politicians were more concerned with making deals with each other and less about political philosophies and principles. Large coalitions were formed, with members being bribed to join them. The liberals, the main political group, was tied together by informal "gentleman's agreements", but these were always in matters of enriching themselves. Indeed, actual governing did not seem to be happening at all, but since only 2 million men had franchises, most of these wealthy landowners did not have to concern themselves with such things as improving the lives of the people they were supposedly representing democratically.

However trasformismo fed into the debates that the Italian parliamentary system was weak and actually failing; it ultimately became associated with corruption. It was perceived as the sacrifice of principles and policies for short term gain. The system of trasformismo was little loved and seemed to be creating a huge gap between 'Legal' (parliamentary and political) Italy, and 'Real' Italy where the politicians became increasingly isolated. This system brought almost no advantages, illiteracy remained the same in 1912 as before the unification era, and backward economic policies, combined with poor sanitary conditions, continued to prevent the country's rural areas from improving.

Francesco Crispi

Francesco Crispi (1818–1901) was Prime Minister for a total of six years, from 1887 until 1891 and again from 1893 until 1896. Historian R.J.B. Bosworth says of his foreign policy that Crispi:

Pursued policies whose openly aggressive character would not be equaled until the days of the Fascist regime. Crispi increased military expenditure, talked cheerfully of a European conflagration, and alarmed his German or British friends with his suggestions of preventative attacks on his enemies. His policies were ruinous, both for Italy's trade with France, and, more humiliatingly, for colonial ambitions in East Africa. Crispi's lust for territory there was thwarted when on 1 March 1896, the armies of Ethiopian Emperor Menelik routed Italian forces at Adowa, ... In what has been defined as an unparalleled disaster for a modern army. Crispi, whose private life (he was perhaps a trigamist) and personal finances...were objects of perennial scandal, went into dishonorable retirement.[36]

Crispi had been in the Depretis cabinet minister and was once a Garibaldi republican. Crispi's major concerns before during 1887–91 was protecting Italy from Austria-Hungary. Crispi worked to build Italy as a great world power through increased military expenditures, advocation of expansionism, and trying to win Germany's favor even by joining the Triple Alliance which included both Germany and Austria-Hungary in 1882 which remained officially intact until 1915. While helping Italy develop strategically, he continued trasformismo and was authoritarian, once suggesting the use of martial law to ban opposition parties. Despite being authoritarian, Crispi put through liberal policies such as the Public Health Act of 1888 and establishing tribunals for redress against abuses by the government.[37]

The overwhelming attention paid to foreign policy alienated the agricultural community which needed help. Both radical and conservative forces in the Italian parliament demanded that the government investigate how to improve agriculture in Italy.[38] The investigation which started in 1877 and was released eight years later, showed that agriculture was not improving, that landowners were swallowing up revenue from their lands and contributing almost nothing to the development of the land. There was aggravation by lower class Italians to the break-up of communal lands which benefited only landlords. Most of the workers on the agricultural lands were not peasants but short-term labourers who at best were employed for one year. Peasants without stable income were forced to live off meager food supplies, disease was spreading rapidly, plagues were reported, including a major cholera epidemic which killed at least 55,000 people.[39]

The Italian government could not deal with the situation effectively due to the mass overspending of the Depretis government that left Italy in huge debt. Italy also suffered economically because of overproduction of grapes for their vineyards in the 1870s and 1880s when France's vineyard industry was suffering from vine disease caused by insects. Italy during that time prospered as the largest exporter of wine in Europe but following the recovery of France in 1888, southern Italy was overproducing and had to split in two which caused greater unemployment and bankruptcies.[40]

Crispi was a colourful and intensely patriotic character. He was a man of enormous energy but with a violent temper. His whole life, public and private, was turbulent, dramatic and marked by a succession of bitter personal hostilities.[41] According to some Crispi's "fiery pride, almost insane touchiness and indifference to sound methods of government" were due to his Albanian inheritance.[42] Although he began life as a revolutionary and democratic figure, his premiership was authoritarian and he showed disdain for Italian liberals. He was born as a firebrand and died as a firefighter.[43] At the end of the 19th century, Crispi was the dominant figure of Italian politics for a decade. He was saluted by Giuseppe Verdi as 'the great patriot'. He was a more scrupulous statesman than Cavour, a more realistic conspirator than Mazzini, a more astute figure than Garibaldi. His death resulted in lengthier obituaries in Europe's press than for any Italian politician since Cavour.[44]

As prime minister in the 1880s and 1890s, Crispi was internationally famous and often mentioned along with world statesmen such as Bismarck, Gladstone and Salisbury. Originally an enlightened Italian patriot and democratic liberal, he went on to become a bellicose authoritarian prime minister and ally and admirer of Bismarck.

Early colonialism

In the late 19th and early 20th century, Italy attempted to join the Great Powers in acquiring colonies, though it found this difficult due to resistance and unprofitable due to heavy military costs and the lesser economic value of spheres of influence remaining when Italy began to colonize.

A number of colonial projects were undertaken by the government. These were done to gain support of Italian nationalists and imperialists, who wanted to rebuild a Roman Empire. Already, there were large Italian communities in Alexandria, Cairo, and Tunis. Italy first attempted to gain colonies by entering a variety of failed negotiations with other world powers to make colonial concessions. Another approach by Italy was to investigate uncolonized, undeveloped lands by sending missionaries to them. The most promising and realistic lands for colonization were parts of Africa. Italian missionaries had already established a foothold at Massawa in the 1830s and had entered deep into Ethiopia.[45]

During the construction of the Suez Canal in Egypt by Britain and France in the 1850s, Cavour believed that this presented an opportunity for Italian access to the East and had wanted the Italian merchant marine to take advantage of the Suez Canal's creation. Following Cavour's initiative, a man named Sapeto was given permission by the Rubattino shipping company to use a ship to establish a station in east Africa as a means of creating a route to the east. Sapeto landed at the Bay of Assab, a part of modern-day Eritrea in 1869. One year later, the land was purchased from the local Sultan by the Rubattino shipping company acting on the behalf of the Italian government. In 1882, Assab officially became an Italian territory, making it Italy's first colony. Though Tunisia would have been a preferable target because of its close proximity to Italy, the threat of reaction by the French made the attempt too dangerous to pursue. Italy could not afford the threat of war, as its industry was not developed. Assab stood as the start of the small colonial adventures that Italy would initially undertake.[46]

.jpg.webp)

On 5 February 1885, taking advantage of Egypt's conflict with Britain, Italian soldiers landed at Massawa in present-day Eritrea, shortly after the fall of Egyptian rule in Khartoum. As was key in Italian foreign policy, the British backed Italy's taking of Massawa from the Egyptians as it aided their occupation efforts.[47] In 1888, Italy annexed Massawa by force, allowing it to pursue its creation of the colony of Italian Eritrea.

In 1885, Italy offered Britain military support for the occupation of Egyptian Sudan, but the British decided that they did not need Italian support to crush the remainder of Egypt, as the forces of Sudanese Muslim rebel Muhammad Ahmad, called the Mahdist army in Sudan, already had crushed remaining Egyptian forces, and Ethiopia's (then called Abyssinia) intervention in Sudan also aided the British.[48] Italy's earlier intervention in Assab set off tensions with Ethiopia, which had territorial aims on Assab, and Italy's official annexation of Ethiopian-claimed Massawa in 1888 increased tensions further.

In 1889, Ethiopia's Emperor Yohannes IV died in battle in Sudan, Menelik II replaced Yohannes as Emperor. Menelik believed he could negotiate with Italy to avoid war and in error allowed Italy's claim to Massawa. Menelik made another serious blunder when he signed an agreement which declared that Ethiopia would work alongside the King of Italy in its dealings with foreign powers, which the Italians interpreted to declare that Ethiopia had in effect made itself a protectorate of Italy.[49] Menelik opposed the Italian interpretation and the differences between the two states grew.

In October 1889, Menelik met with a Russian officer who was sent to discuss merging the Russian and Abyssinian orthodox churches, but Menelik was more concerned over Italy's massing army in Eritrea.[49] The meeting was used by Menelik to show unity between Ethiopia and Russia against Italian interests in the area.[49]

Russia's own interests in East Africa led Russia's government to send large amounts of modern weaponry to the Ethiopians to hold back an Italian invasion. In response, Britain decided to back the Italians to challenge Russian influence in Africa and declared that all of Ethiopia was within the sphere of Italian interest. On the verge of war, Italian militarism and nationalism reached a peak, with Italians flocking to the Italian army, hoping to take part in the upcoming war.[50]

In 1895, Ethiopia abandoned its agreement to follow Italian foreign policy, and Italy used the renunciation as a reason to invade Ethiopia, with the support of the United Kingdom.[51] The Italian and British army failed on the battlefield of Adowa, as the Ethiopians were numerical superior and supported by Russia and France with modern weapons; the sheer large numbers of the Ethiopian warriors forced Italy eventually to retreat into Eritrea.[52] Ethiopia would remain independent from Italy and other colonial powers until it was occupied in 1936 but then subsequently liberated after World War II.

Giovanni Giolitti

In 1892, Giovanni Giolitti became Prime Minister of Italy for his first term. Though his first government quickly collapsed a year later, Giolitti returned in 1903 to lead Italy's government during a fragmented reign that lasted until 1914. Giolitti had spent his earlier life as a civil servant, and then took positions within the cabinets of Crispi. Giolitti was the first long-term Italian Prime Minister in many years and was so because he mastered the political concept of trasformismo by manipulating, coercing and bribing officials to his side. In elections during Giolitti's government, voting fraud was common, and Giolitti helped improve voting only in well-off, more supportive areas, while attempting to isolate and intimidate poor areas where opposition was strong.[53]

On May 5, 1898, workers in Milan organized a strike to demonstrate against the government of Antonio Starrabba di Rudinì, holding it responsible for the general increase of prices and for the famine that was affecting the country. In response infantry, cavalry and artillery were brought into the city and General Fiorenzo Bava Beccaris ordered his troops to fire on demonstrators. According to the government, there were 118 dead and 450 wounded. King Umberto I praised the General and awarded him the medal of Grande Ufficiale dell'Ordine Militare dei Savoia. The decoration exacerbated the Italian population's indignation. On the other hand, Antonio di Rudinì was forced to resign in July 1898.

On 29 July 1900, at Monza, King Umberto I was assassinated by the anarchist Gaetano Bresci who claimed he had come directly from America to avenge the victims of the repression, and the offense given by the decoration awarded to General Bava Beccaris.

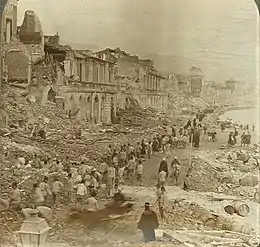

Southern Italy was in terrible shape prior to and during Giolitti's tenure as Prime Minister. Four-fifths of southern Italians were illiterate and the dire situation there ranged from problems of large numbers of absentee landlords to rebellion and even starvation.[54] Corruption was such a large problem that Giolitti himself admitted that there were places "where the law does not operate at all".[55] Natural disasters like earthquakes and landslides were a common source of destruction in southern Italy, often killing hundreds of people in each disaster, and southern Italy's poverty made repair work very difficult to do. Giolitti's small response to the major earthquake in Messina in 1908 was blamed for the high number of deaths which numbered at 50,000 people. The Messina earthquake infuriated southern Italians who claimed that Giolitti favoured the rich north over them. One study released in 1910 examined tax rates in north, central and southern Italy indicated that northern Italy with 48% of the nation's wealth paid 40% of the nation's taxes, while the south with 27% of the nation's wealth paid 32% of the nation's taxes.[56]

According to his biographer Alexander De Grand, Giolitti was Italy's most notable Prime Minister after Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour.[57] Like Cavour, Giolitti came from Piedmont; like other leading Piedmontese politicians, he combined a pragmatism with an Enlightenment faith in progress through material advancement. An able bureaucrat, he had little sympathy for the idealism that had inspired much of the Risorgimento. He tended to see discontent as rooted in frustrated self-interest and believed that most opponents had their price and could be transformed eventually into allies.[58]

The primary objective of Giolittian politics was to govern from the political centre with slight and well controlled fluctuations, now in a conservative direction, then in a progressive one, trying to preserve the institutions and the existing social order.[57] Critics from the political right considered him a socialist due to the courting of socialist votes in parliament in exchange for political favours; writing for the Corriere della Sera, Luigi Albertini mockingly described Giolitti as "the Bolshevik from the Most Holy Annunciation" after his Dronero speech advocating Italy's neutrality during World War I like the Socialists. Critics from the political left called him ministro della malavita ("Minister of the Underworld"), a term coined by the historian Gaetano Salvemini, accusing him of winning elections with the support of criminals.[57][59]

According to one study, Giolitti represented a new kind of liberalism, noting that "Giolitti's ability to muster the votes in the Chamber for the reforms he deemed necessary established him as the undisputed political leader of Italy for over a decade. His program of reforms also made him the most significant Italian practitioner of European New Liberalism. Giolitti did not contribute theoretical works to this new intellectual current, but he put into practice several of the tenets of New Liberalism before some of the theorists of the intellectual current had shown awareness of them."[60]

Political upheavals

Politics were in turmoil. The expansion of the electorate from 3 million to 8.5 million voters in 1912 brought in many workers and peasants, with gains for the Socialist and Catholic forces. New interest groups became better organized, with local organizations and influential newspapers, such as the Catholics, the nationalists, the farmers and the sugar growers. Giolitti lost his once-powerful hold on the press. During Giolitti's three-year absence, the Italian liberal establishment weakened with the rise of Italian nationalism. The nationalists were becoming a popular movement with popular leadership figures such as Enrico Corradini and the revolutionary Gabriele D'Annunzio. Nationalists began demanding the return of Italian-populated territories in Austria, demanded Croatian-populated Dalmatia, spoke of the need for Italy to expand territorially into Africa, particularly Libya. Giolitti negotiated with the nationalists demands and began planning an invasion of Ottoman Turkish-held Libya.[61]

The Italian Catholic Electoral Union (Unione elettorale cattolica italiana) was formed in 1905 to coordinate Catholic voters. It was formed in 1905 after the suppression of the Opera dei Congressi following the encyclical Il fermo proposito of Pope Pius X. The Union was headed in 1909–16 by Count Ottorino Gentiloni. The Gentiloni pact of 1913 brought many new Catholic voters into politics, where they supported the Liberal party of Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti. By the terms of the pact, the Union directed Catholic voters to Giolitti supporters who agreed to favor the Church's position on such key issues as funding private Catholic schools, and blocking a law allowing divorce.[62]

However the Socialists divided over Italy's conquest of Libya in 1911–12. Meanwhile, the nationalists grew in power. The Gentiloni pact brought new Catholic support to the Liberals, who were thus moving to more conservative positions. Increasingly the Radicals and Socialists on the Left rejected Giolitti, especially his pro-Catholic policies. In October 1913 he formed a new government with the clericals. Giolitti stepped down and the new government was headed by Antonio Salandra, a right-wing conservative.[63]

Until 1922, Italy was a constitutional monarchy with a parliament; in 1913, the first universal male suffrage election was held. The so-called Statuto Albertino, which Carlo Alberto conceded in 1848 remained unchanged, even if the kings usually abstained from abusing their extremely large powers (for example, senators were not elected but chosen by the king).

Colonial empire

In 1911, Giolitti's government agreed to sending forces to occupy Libya. Italy declared war on the Ottoman Empire which held Libya as a colony. The war ended only a year later, but the occupation resulted in acts of extreme discrimination towards Libyans such as the forced deportation of Libyans to the Tremiti Islands in October 1911 and by 1912, a third of these Libyan refugees had died due to lack of food supplies and shelter from the Italian occupation forces.[64] Italian control of the area was weak, leading to twenty years of conflict with the Senussi religious order which was the main political and religious authority in the Libyan hinterlands. The invasion of Libya did mark a turn in direction for the opposition to the Italian government, revolutionaries became divided, some adopting nationalist lines, while others retaining socialist lines.[65] The annexation of Libya caused nationalists to advocate Italy's domination of the Mediterranean Sea by occupying Greece as well as the Adriatic coastal region of Dalmatia.[65]

While the success of the Libyan War improved the status of the nationalists, it did not help Giolitti's administration as a whole. The war radicalized the Italian Socialist Party with anti-war revolutionaries led by future-Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini calling for violence to bring down the government. Giolitti could no longer rely on the dwindling reformist socialist elements and was forced to concede even further to the right, Giolitti dropped all anticlericalism and reached out to clericals which alienated his moderate liberal base leaving him with an unsteady coalition which collapsed in 1914. By the end of his tenure, Italians detested him and the liberal establishment for the fraudulent elections, the divided society, and the failure and corruption of trasformiso organized governments. Giolitti would return as Prime Minister only briefly in 1920, but the era of liberalism was effectively over in Italy.

Italian colonial ventures began with the acquisition of the ports of Asseb in 1869 and Massawa in 1885 in what is now Eritrea. These areas were claimed by Ethiopia at the time, and when Ethiopia went into turmoil at the death of Emperor Yohannes IV Italy moved into the northern Ethiopian highlands. However, further expansion was checked by a revival of Ethiopian power under Emperor Menelik II which led to the defeat of Italian forces at the battle of Adua. However, Italy was still able to secure the northern highlands in the Treaty of Wuchale, ending its conflict with Ethiopia until 1935.

Around the same time Italy began to colonize Somalia. It avoided the other powers carving out domains in that area but gradually gained the southern Somali coast beginning with the Sultanate of Hobyo and the Sultanate of Majeerteen in 1888 and continuing with gradual acquisitions until 1925 when Chisimayu Region belonging to the British protectorate of Zanzibar was given to Italy.

World War I and failure of the liberal state

Prelude to war and internal dilemma

In the lead-up to World War I, the Kingdom of Italy faced many short- and long-term problems in determining its allies and objectives. Italy's recent success in occupying Libya as a result of the Italo-Turkish War had sparked tension with its Triple Alliance allies, Germany and Austria-Hungary, because both countries had been seeking closer relations with the Ottoman Empire. In Munich, Germans reacted to Italy's aggression by singing anti-Italian songs.[66] Italy's relations with France were also in bad shape: France felt betrayed by Italy's support of Prussia in the Franco-Prussian War, opening the possibility of war erupting between the two countries.[67] Italy's relations with the United Kingdom had also been impaired by constant Italian demands for more recognition on the international stage following the occupation of Libya and its demands that other nations accept its spheres of influence in Eastern Africa and the Mediterranean Sea.[68]

In the Mediterranean Sea, Italy's relations with the Kingdom of Greece were aggravated when Italy occupied the Greek-populated Dodecanese Islands, including Rhodes, from 1912 to 1914. The Ottoman Empire had formerly controlled these islands. Italy and Greece were also in open rivalry over the desire to occupy Albania.[69] King Victor Emmanuel III himself was uneasy about Italy pursuing distant colonial adventures and said that Italy should prepare to take back Italian-populated land from Austria-Hungary as the "completion of the Risorgimento".[70] This idea put Italy at odds with Austria-Hungary.

A major hindrance to Italy's decision on what to do about the war was the political instability throughout Italy in 1914. After the formation of the government of Prime Minister Antonio Salandra in March 1914, the government attempted to win the support of nationalists. It moved to the political right.[71] At the same time, the left became more repulsed by the government after the killing of three anti-militarist demonstrators in June.[71] Many elements of the left including syndicalists, republicans, and anarchists protested against this and the Italian Socialist Party declared a general strike in Italy.[72] The protests that ensued became known as "Red Week" as leftists rioted and various acts of civil disobedience occurred in major cities and small towns such as seizing railway stations, cutting telephone wires and burning tax-registers.[71] However, only two days later the strike was officially called off, though the civil strife continued. Militarist nationalists and anti-militarist leftists fought on the streets until the Italian Royal Army forcefully restored calm after using thousands of men to put down the various protesting forces.[71] Following the invasion of Serbia by Austria-Hungary in 1914, World War I broke out. Despite Italy's official alliance with Germany and membership in the Triple Alliance, the Kingdom of Italy initially remained neutral, claiming that the Triple Alliance was only for defensive purposes.[73]

.png.webp)

In Italy, society was divided over the war: Italian socialists generally opposed the war and supported pacifism, while nationalists militantly supported the war. Long-time nationalists Gabriele D'Annunzio and Luigi Federzoni, together with a former socialist journalist and new convert to nationalist sentiment, future Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, demanded that Italy join the war. For nationalists, Italy had to maintain its alliance with the Central Powers to gain colonial territories at the expense of France. For the liberals, the war presented Italy a long-awaited opportunity to use an alliance with the Entente to gain certain Italian-populated and other territories from Austria-Hungary, which had long been part of Italian patriotic aims since unification. In 1915, relatives of Italian revolutionary and republican hero Giuseppe Garibaldi died on the battlefield of France, where they had volunteered to fight. Federzoni used the memorial services to declare the importance of Italy joining the war and to warn the monarchy of the consequences of continued disunity in Italy if it did not:

Italy has awaited this since 1866 her truly a national war, to feel unified, at last, renewed by the unanimous action and identical sacrifice of all her sons. Today, while Italy still wavers before the necessity imposed by history, the name of Garibaldi, resanctified by blood, rises again to warn her that she will not be able to defeat the revolution save by fighting and winning her national war.

– Luigi Federzoni, 1915[74]

Mussolini used his new newspaper Il Popolo d'Italia and his strong oratorical skills to urge a broad political audience – ranging from right-wing nationalists to patriotic revolutionary leftists – to support Italy's entry into the war to gain back Italian-populated territories from Austria-Hungary, by saying "enough of Libya, and on to Trento and Trieste".[74] Although the left was traditionally opposed to war, Mussolini claimed that this time it was in their interest to join the war to tear down the aristocratic Hohenzollern dynasty of Germany which he claimed was the enemy of all European workers.[75] Mussolini and other nationalists warned the Italian government that Italy must join the war or face revolution and called for violence against pacifists and neutralists.[76]

With nationalist sentiment firmly on the side of reclaiming Italian territories of Austria-Hungary, Italy entered negotiations with the Triple Entente. The negotiations ended successfully in April 1915 when the London Pact was brokered with the Italian government. The pact ensured Italy the right to attain all Italian-populated lands it wanted from Austria-Hungary, as well as concessions in the Balkan Peninsula and suitable compensation for any territory gained by the United Kingdom and France from Germany in Africa.[77] The proposal fulfilled the desires of Italian nationalists and Italian imperialism and was agreed to. Italy joined the Triple Entente in its war against Austria-Hungary.

The reaction in Italy was divided: former Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti was furious over Italy's decision to go to war against its former allies, Germany and Austria-Hungary. Giolitti claimed that Italy would fail in the war, predicting high numbers of mutinies, Austro-Hungarian occupation of even more Italian territory and that the failure would produce a catastrophic rebellion that would destroy the liberal-democratic monarchy and the liberal-democratic secular institutions of the state.[78]

Freemasonry was an influential semi-secret force in Italian politics with a strong presence among professionals and the middle class across Italy, as well as among the leadership in parliament, public administration, and the army. The two main organization were the Grand Orient and the Grand Lodge of Italy. They had 25,000 members in 500 or more lodges. Freemasons took on the challenge of mobilizing the press, public opinion, and the leading political parties in support of Italy's joining the war as an ally of France and Great Britain. In 1914-15 they temporarily dropped their traditional pacifistic rhetoric and adopted the objectives of the nationalists. Freemasonry had historically promoted cosmopolitan universal values, and by 1917 onwards they reverted to their internationalist stance and pressed for the creation of a League of Nations to promote a new post-war universal order based upon the peaceful coexistence of independent and democratic nations.[79]

Italy entered into the First World War in 1915 also with the aim of completing national unity with the annexation of Trentino-Alto Adige and Julian March: for this reason, the Italian intervention in the First World War is also considered the Fourth Italian War of Independence,[80] in a historiographical perspective that identifies in the latter the conclusion of the unification of Italy, whose military actions began during the revolutions of 1848 with the First Italian War of Independence.[81][82] After the Capture of Rome (1870), almost the whole of Italy was united in a single state, Kingdom of Italy. However, the so-called "irredent lands" were missing, that is, Italian-speaking, geographically or historically Italian lands that were not yet part of the unitary state. Among the irredent lands still belonging to Austria-Hungary were usually indicated as such: Julian March (with the city of Fiume), Trentino-Alto Adige and Dalmatia. The Italian irredentism movement, which aimed at the reunification of the aforementioned with the motherland and therefore their consequent redemption, was active precisely between the last decades of the 19th century and the early 20th century. It was precisely in the irredentist sphere that the theme of the need for a "Fourth Italian War of Independence" against Austria-Hungary began to develop in the last decades of the 19th century,[83][84] when Italy was still firmly incorporated in the Triple Alliance; also the Italo-Turkish War was seen, in the irredentist context, as part of this theme[85]

Italy's war effort

The front on the Austro-Hungarian border was 650 km (400 mi) long, stretching from the Stelvio Pass to the Adriatic Sea. Italian forces were numerically superior but this advantage was negated by the difficult terrain. Further, the Italians lacked strategic and tactical leadership. The Italian commander-in-chief was Luigi Cadorna, a staunch proponent of the frontal assault whose tactics cost the lives of hundreds of thousands of Italian soldiers. His plan was to attack on the Isonzo front, with the dream of breaking over the Karst Plateau into the Carniolan Basin, taking Ljubljana and threatening the Austro-Hungarian Empire's capital Vienna. It was a Napoleonic plan, which had no realistic chance of success in an age of barbed wire, machine guns, and indirect artillery fire, combined with hilly and mountainous terrain.[88]

The first shells were fired in the dawn of 24 May 1915 against the enemy positions of Cervignano del Friuli, which was captured a few hours later. On the same day the Austro-Hungarian fleet bombarded the railway stations of Manfredonia and Ancona. The first Italian casualty was Riccardo Di Giusto. The main effort was to be concentrated in the Isonzo and Vipava valleys and on the Karst Plateau, in the direction of Ljubljana. The Italian troops had some initial successes, but as in the Western Front, the campaign soon evolved into trench warfare. The main difference was that the trenches had to be dug in the Alpine rocks and glaciers instead of in the mud, and often up to 3,000 m (9,800 ft) of altitude.

The outset of the campaign against Austria-Hungary looked to initially favor Italy: Austria-Hungary's army was spread to cover its fronts with Serbia and Russia and Italy had a numerical superiority against the Austro-Hungarian Army. However, this advantage was never fully utilized because Italian military commander Luigi Cadorna insisted on a dangerous frontal assault against Austria-Hungary in an attempt to occupy the Slovenian plateau and Ljubljana. This assault would put the Italian army not far away from Austria-Hungary's imperial capital, Vienna. After eleven offensives with an enormous loss of life and the final victory of the Central Powers, the Italian campaign to take Vienna collapsed.

Upon entering the war, geography was also difficult for Italy as its border with Austria-Hungary was along mountainous terrain. In May 1915, Italian forces at 400,000 men along the border outnumbered the Austrian and Germans almost four to one.[90] However, Austrian defences hold off the Italian offensive.[91] The battles with the Austro-Hungarian Army along the Alpine foothills in trench warfare were drawn-out, long engagements with little progress.[92] Italian officers were poorly trained in contrast to the Austro-Hungarian and German armies, Italian artillery was inferior to the Austrian machine guns, and the Italian forces had a dangerously low supply of ammunition; this shortage would continually hamper attempts to make advances into Austrian territory.[91] This combined with the constant replacement of officers by Cadorna resulted in few officers gaining the experience necessary to lead military missions.[93] In the first year of the war, poor conditions on the battlefield led to cholera outbreaks, causing many Italian soldiers to die.[94] Despite these serious problems, Cadorna refused to back down on the strategy of offence. Naval battles occurred between the Italian Royal Navy (Regia Marina) and the Austro-Hungarian Navy. The Austro-Hungarian fleet outclassed Italy's warships, and the situation was made direr for Italy in that both the French Navy and the (British) Royal Navy were not sent into the Adriatic Sea. Their respective governments viewed the Adriatic Sea as "far too dangerous to operate in due to the concentration of the Austro-Hungarian fleet there".[94]

Morale fell among Italian soldiers who lived a tedious life when not on the front lines, as they were forbidden to enter theaters or bars, even when on leave. However, alcohol was made freely available to the soldiers when battles were about to occur. Groups of soldiers worked to create improvized whorehouses.[95] To maintain morale, the Italian army had propaganda lectures on the importance of the war to Italy, especially to retrieve Trento and Trieste from Austria-Hungary.[95] Some of these lectures were carried out by popular nationalist war proponents such as Gabriele D'Annunzio. D'Annunzio himself would participate in several paramilitary raids on Austrian positions along the Adriatic Sea coastline during the war and temporarily lost his sight after an air raid.[96] Prominent pro-war advocate Benito Mussolini was prevented from giving lectures by the government, most likely because of his revolutionary socialist past.[95]

The Italian government became increasingly aggravated in 1915 with the passive nature of the Serbian army, which had not engaged in a serious offensive against Austria-Hungary for months.[97] The Italian government blamed Serbian military inactiveness for allowing the Austro-Hungarians to muster their armies against Italy.[98] Cadorna suspected that Serbia was attempting to negotiate an end to fighting with Austria-Hungary and addressed this to foreign minister Sidney Sonnino, who himself bitterly claimed that Serbia was an unreliable ally.[98] Relations between Italy and Serbia became so cold that the other Allied nations were forced to abandon the idea of forming a united Balkan front against Austria-Hungary.[98] In negotiations, Sonnino remained prepared to allow Bosnia to join Serbia, but refused to discuss the fate of Dalmatia, which was claimed both by Italy and by Pan-Slavists in Serbia.[98] As Serbia fell to the Austro-Hungarian and German forces in 1915, Cadorna proposed sending 60,000 men to land in Thessaloniki to help the Serbs now in exile in Greece and the Principality of Albania to fight off the opposing forces, but the Italian government's bitterness to Serbia resulted in the proposal being rejected.[98]

In the spring of 1916, Austro-Hungarians counterattacked in the Altopiano of Asiago, towards Verona and Padova, in their Strafexpedition, but were defeated by the Italians. In August, after the Battle of Doberdò, the Italians also captured the town of Gorizia; the front remained static for over a year. At the same time, Italy faced a shortage of warships, increased attacks by submarines, soaring freight charges threatening the ability to supply food to soldiers, lack of raw materials and equipment, and Italians faced high wartime taxes.[100] Austro-Hungarian and German forces had gone deep into Northern Italian territory. Finally, in November 1916, Cadorna ceased offensive operations and began a defensive approach. In 1917, France, the United Kingdom and the United States offered to send troops to Italy to help it fend off the offensive of the Central Powers. Still, the Italian government refused as Sonnino did not want Italy to be seen as a client state of the Allies and preferred isolation as the more brave alternative.[101] Italy also wanted to keep Greece out of the war as the Italian government feared that, should Greece the Allies, it would move to annex Italian-claimed Albania.[102] The Venizelist pro-war advocates in Greece failed to succeed in pressuring Constantine I of Greece to bring Italy into the conflict, and Italian aims on Albania remained unthreatened.[102]

The Russian Empire collapsed in 1917 Russian Revolution, eventually resulting in the rise of the communist Bolshevik regime of Vladimir Lenin. The resulting marginalization of the Eastern Front allowed for more Austro-Hungarian and German forces to arrive on the front against Italy. Internal dissent against the war grew with increasingly poor economic and social conditions in Italy due to the strain of the war. Much of the profit of the war was being made in the cities, while rural areas were losing income.[107] The number of men available for agricultural work had fallen from 4.8 million to 2.2 million, though with the help of women, agricultural production managed to be maintained at 90% of its pre-war total during the war.[108] Many pacifists and internationalist Italian socialists turned to Bolshevism and advocated negotiations with the workers of Germany and Austria-Hungary to help end the war and bring about Bolshevik revolutions.[108] Avanti!, the newspaper of the Italian Socialist Party, declared: "Let the bourgeoisie fight its war".[109] Leftist women in Northern Italian cities led protests demanding action against the high cost of living and demanding an end to the war.[110] In Milan in May 1917, communist revolutionaries organized and engaged in rioting, calling for an end to the war and managed to close down factories and stop public transportation.[111] The Italian Army was forced to enter Milan with tanks and machine guns to face communists and anarchists who fought violently until 23 May, when the Army gained control of the city with almost 50 people killed (three of which were Italian soldiers) and over 800 people arrested.[111]

After the disastrous Battle of Caporetto in 1917, Italian forces were forced far back into Italian territory as far as the Piave river. The humiliation led to the appointment of Vittorio Emanuele Orlando as Prime Minister, who managed to solve some of Italy's wartime problems. Orlando abandoned the previous isolationist approach to the war and increased coordination with the Allies. The convoy system was introduced to fend off submarine attacks and allowed Italy to end food shortages from February 1918 onward. Also, Italy received more raw materials from the Allies.[112] The new Italian chief of staff, Armando Diaz, ordered the Army to defend the Monte Grappa summit, where fortified defences were constructed; despite numerically inferior, the Italians managed to repel the Austro-Hungarian and German Army. 1918 also saw the beginning of the official suppression of enemy aliens. The Italian government increasingly suppressed the Italian socialists.

At the Battle of the Piave River, the Italian Army managed to hold off the Austro-Hungarian and German armies. The opposing armies repeatedly failed afterwards in major battles such as Battle of Monte Grappa and the Battle of Vittorio Veneto. After four days, the Italian Army defeated the Austro-Hungarian Army in the latter battle, aided by British and French divisions and the fact that the Imperial-Royal Army started to melt away as news arrived that the constituent regions of the Dual Monarchy had declared independence. Austria-Hungary ended the fighting against Italy with the armistice on 4 November 1918, one week before the 11 November armistice on the armistice on the Western front. The Italian victory,[113][114][115] which was announced by the Bollettino della Vittoria and the Bollettino della Vittoria Navale.

The Italian government was infuriated by the Fourteen Points of Woodrow Wilson, the President of the United States, as advocating national self-determination which meant that Italy would not gain Dalmatia as had been promised in the Treaty of London.[118] In the Parliament of Italy, nationalists condemned Wilson's fourteen points as betraying the Treaty of London, while socialists claimed that Wilson's points were valid and claimed the Treaty of London was an offense to the rights of Slavs, Greeks and Albanians.[118] Negotiations between Italy and the Allies, particularly the new Yugoslav delegation (replacing the Serbian delegation), agreed to a trade off between Italy and the new Kingdom of Yugoslavia, which was that Dalmatia, despite being claimed by Italy, would be accepted as Yugoslav, while Istria, claimed by Yugoslavia, would be accepted as Italian.[119]

During the war, the Italian Royal Army increased in size from 15,000 men in 1914 to 160,000 men in 1918, with 5 million recruits in total entering service during the war.[93] This came at a terrible cost: by the end of the war, Italy had lost 700,000 soldiers and had a budget deficit of twelve billion lira. Italian society was divided between the majority of pacifists who opposed Italian involvement in the war and the minority of pro-war nationalists who had condemned the Italian government for not having immediately gone to war with Austria-Hungary in 1914.

Italy's territorial settlements and the reaction

As the war came to an end, Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando met with British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, Prime Minister of France Georges Clemenceau and United States President Woodrow Wilson in Versailles to discuss how the borders of Europe should be redefined to help avoid a future European war.

The talks provided little territorial gain to Italy because, during the peace talks, Wilson promised freedom to all European nationalities to form their nation-states. As a result, the Treaty of Versailles did not assign Dalmatia and Albania to Italy as had been promised in the Treaty of London. Furthermore, the British and French decided to divide the German overseas colonies into their mandates, with Italy receiving none of them. Italy also gained no territory from the breakup of the Ottoman Empire, despite a proposal being issued to Italy by the United Kingdom and France during the war, only to see these nations carve up the Ottoman Empire between themselves (also exploiting the forces of the Arab Revolt). Despite this, Orlando agreed to sign the Treaty of Versailles, which caused uproar against his government. The Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1919) and the Treaty of Rapallo (1920) allowed the annexation of Trentino Alto-Adige, Julian March, Istria, Kvarner as well as the Dalmatian city of Zara.

Furious over the peace settlement, the Italian nationalist poet Gabriele D'Annunzio led disaffected war veterans and nationalists to form the Free State of Fiume in September 1919. His popularity among nationalists led him to be called Il Duce ("The Leader"), and he used black-shirted paramilitary in his assault on Fiume. The leadership title of Duce and the blackshirt paramilitary uniform would later be adopted by the Fascist movement of Benito Mussolini. The demand for the Italian annexation of Fiume spread to all sides of the political spectrum, including Mussolini's Fascists.[120] D'Annunzio's stirring speeches drew Croat nationalists to his side and also kept contact with the Irish Republican Army and Egyptian nationalists.[121]

The subsequent Treaty of Rome (1924) led to the annexation of the city of Fiume to Italy. Italy did not receive other territories promised by the Treaty of London (1915), such as Dalmatia, so this outcome was denounced as a mutilated victory. The rhetoric of mutilated victory was adopted by Benito Mussolini and led to the rise of Italian fascism, becoming a key point in the propaganda of Fascist Italy. Historians regard mutilated victory as a "political myth", used by fascists to fuel Italian imperialism and obscure the successes of liberal Italy in the aftermath of World War I.[122] Italy also gained a permanent seat in the League of Nations's executive council.

Fascist regime, World War II, and Civil War (1922–1946)

Mussolini in war and postwar

In 1914, Benito Mussolini was forced out of the Italian Socialist Party after calling for Italian intervention in the war against Austria-Hungary. Before World War I, Mussolini had opposed military conscription, protested against Italy's occupation of Libya and was the editor of the Socialist Party's official newspaper, Avanti!, but over time he simply called for revolution without mentioning class struggle.[123] In 1914, Mussolini's nationalism enabled him to raise funds from Ansaldo (an armaments firm) and other companies to create his newspaper, Il Popolo d'Italia, which at first attempted to convince socialists and revolutionaries to support the war.[124] The Allied Powers, eager to draw Italy to the war, helped finance the newspaper.[125] Later, after the war, this publication would become the official newspaper of the Fascist movement. During the war, Mussolini served in the Army and was wounded once.[126]

Following the end of the war and the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, Mussolini created the Fasci di Combattimento or Combat League. It was originally dominated by patriotic socialist and syndicalist veterans who opposed the pacifist policies of the Italian Socialist Party. This early Fascist movement had a platform more inclined to the left, promising social revolution, proportional representation in elections, women's suffrage (partly realized in 1925) and dividing rural private property held by estates.[127][128] They also differed from later Fascism by opposing censorship, militarism and dictatorship.[129] Mussolini claimed that "we are libertarians above all, loving liberty for everyone, even for our enemies" and said that freedom of thought and speech were among the "highest expressions of human civilization."[130] On 15 April 1919, the Fascists made their debut in political violence when a group of members from the Fasci di Combattimento attacked the offices of Avanti!.

At the same time, the so-called Biennio Rosso (red biennium) took place in the two years following the first world war in a context of economic crisis, high unemployment and political instability. The 1919–20 period was characterized by mass strikes, worker manifestations as well as self-management experiments through land and factory occupations. In Turin and Milan, workers councils were formed and many factory occupations took place under the leadership of anarcho-syndicalists. The agitations also extended to the agricultural areas of the Padan plain and were accompanied by peasant strikes, rural unrests and guerilla conflicts between left-wing and right-wing militias.

.jpg.webp)

On 15 April 1919, the Fascists made their debut in political violence when a group of members from the Fasci di Combattimento attacked the offices of Avanti!. But they found little public support, and in the elections of November 1919, the Fascists suffered a heavy defeat, accompanied by a rapid loss of membership.[129] In response, Mussolini moved the organization away from the left and turned the revolutionary movement into an electoral movement in 1921 named the Partito Nazionale Fascista (National Fascist Party). The party echoed the nationalist themes of D'Annunzio and rejected parliamentary democracy while still operating within it in order to destroy it. Mussolini changed his original revolutionary policies, such as moving away from anti-clericalism to supporting the Roman Catholic Church and abandoned his public opposition to the monarchy.[131] Support for the Fascists began to grow in 1921, and pro-Fascist army officers began taking arms and vehicles from the army to use in counter-revolutionary attacks on socialists.[132]

In 1920, Giolitti came back as Prime Minister in an attempt to solve the deadlock. One year later, Giolitti's government had become unstable, and a growing socialist opposition further endangered his government. Giolitti believed that the Fascists could be toned down and used to protect the state from the socialists. He decided to include Fascists on his electoral list for the 1921 elections.[131] In the elections, the Fascists did not make large gains. Still, Giolitti's government failed to gather a large enough coalition to govern and offered the Fascists placements in his government. The Fascists rejected Giolitti's offers, forcing him to resign as his coalition no longer had enough support in parliament.[133] Many descendants of those who had served Garibaldi's revolutionaries during unification were won over to Mussolini's nationalist revolutionary ideals.[134] His advocacy of corporatism and futurism had attracted advocates of the "third way",[134] but most importantly, he had won over politicians like Facta and Giolitti. He did not condemn him for his Blackshirts' mistreatment of socialists.[135]

March on Rome and the Fascist government

In October 1922, Mussolini took advantage of a general strike by workers and announced his demands to the government to give the Fascist Party political power or face a coup. With no immediate response, a small number of Fascists began a long trek across Italy to Rome, which was known as the "March on Rome", claiming to Italians that Fascists intended to restore law and order. Mussolini himself did not participate until the very end of the march, with D'Annunzio being hailed as the leader of the march until it was learned that he had been pushed out of a window and severely wounded in a failed assassination attempt, depriving him of the possibility of leading an actual coup d'état orchestrated by an organization founded by himself. Under the leadership of Mussolini, the Fascists demanded Prime Minister Luigi Facta's resignation and that Mussolini be named Prime Minister. Although the Italian Army was far better armed than the Fascist paramilitaries, the Italian government under King Vittorio Emmanuele III faced a political crisis. The King was forced to decide which of the two rival movements in Italy would form the new government: Mussolini's Fascists or the anti-royalist Italian Socialist Party, ultimately deciding to endorse the Fascists.[136][137]

Upon taking power, Mussolini formed a coalition with nationalists and liberals. In 1923, Mussolini's coalition passed the electoral Acerbo Law, which assigned two thirds of the seats to the party that achieved at least 25% of the vote. The Fascist Party used violence and intimidation to achieve the threshold in the 1924 election, thus obtaining control of Parliament. Socialist deputy Giacomo Matteotti was assassinated after calling for a nullification of the vote because of the irregularities.

The parliament opposition, mainly comprising the Italian Socialist Party, Italian Liberal Party, Italian People's Party and Italian Communist Party, responded to Matteotti's assassination with the Aventine Secession, or with the withdrawal of parliamentarians from the Chamber of Deputies in 1924–25. The secession was named after the Aventine Secession in ancient Rome. This act of protest heralded the assumption of total power by Benito Mussolini and his National Fascist Party and the establishment of a one-party dictatorship in Italy. It was unsuccessful in opposing the National Fascist Party, and after two years the Chamber of Deputies ruled that the 123 Aventine deputies had forfeited their positions. In the following years, many of the "Aventinian" deputies were forced into exile or imprisoned.

Over the next four years, Mussolini eliminated nearly all checks and balances on his power. On 24 December 1925, he passed a law that declared he was responsible to the king alone, making him the sole person able to determine Parliament's agenda. Local governments were dissolved, and appointed officials (called "Podestà") replaced elected mayors and councils. In 1928, all political parties were banned, and parliamentary elections were replaced by plebiscites in which the Grand Council of Fascism nominated a single list of 400 candidates.

.svg.png.webp)