History of Rome

The history of Rome includes the history of the city of Rome as well as the civilisation of ancient Rome. Roman history has been influential on the modern world, especially in the history of the Catholic Church, and Roman law has influenced many modern legal systems. Roman history can be divided into the following periods:

- Pre-historical and early Rome, covering Rome's earliest inhabitants and the legend of its founding by Romulus

- The period of Etruscan dominance and the regal period, in which, according to tradition, Romulus was the first of seven kings

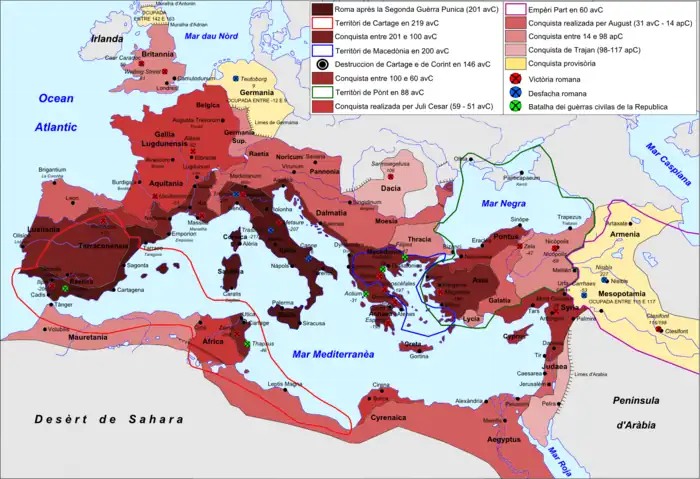

- The Roman Republic, which commenced in 509 BC when kings were replaced with rule by elected magistrates. The period was marked by vast expansion of Roman territory. During the 5th century BC, Rome gained regional dominance in Latium. With the Punic Wars from 264 to 146 BC, ancient Rome gained dominance over the Western Mediterranean, displacing Carthage as the dominant regional power.

- The Roman Empire followed the Republic, which waned with the rise of Julius Caesar, and by all measures concluded after a period of civil war and the victory of Caesar's adopted son, Octavian, in 27 BC over Mark Antony.

- The Western Roman Empire collapsed in 476 after the city was conquered by the Ostrogothic Kingdom. Consequently Rome's power declined, and it eventually became part of the Eastern Roman Empire, as the Duchy of Rome, from the 6th to 8th centuries. At this time, the city was reduced to a fraction of its former size, being sacked several times in the 5th to 6th centuries, even temporarily depopulated entirely.[1]

- Medieval Rome is characterized by a break with Constantinople and the formation of the Papal States. The Papacy struggled to retain influence in the emerging Holy Roman Empire, and during the saeculum obscurum, the population of Rome fell to as low as 30,000 inhabitants. Following the East–West Schism and the limited success in the Investiture Controversy, the Papacy did gain considerable influence in the High Middle Ages, but with the Avignon Papacy and the Western Schism, the city of Rome was reduced to irrelevance, its population falling below 20,000. Rome's decline into complete irrelevance during the medieval period, with the associated lack of construction activity, assured the survival of very significant ancient Roman material remains in the centre of the city, some abandoned and others continuing in use.

- The Roman Renaissance occurred in the 15th century, when Rome replaced Florence as the centre of artistic and cultural influence. The Roman Renaissance was cut short abruptly with the devastation of the city in 1527, but the Papacy reasserted itself in the Counter-Reformation, and the city continued to flourish during the early modern period. Rome was annexed by Napoleon and was part of the First French Empire from 1798 to 1814.

- Modern history, the period from the 19th century to the present. Rome came under siege again after the Allied invasion of Italy and was bombed several times. It was declared an open city on 14 August 1943. Rome became the capital of the Italian Republic (established in 1946). With a population of 4.4 million (as of 2015; 2.9 million within city limits), it is the largest city in Italy. It is among the largest urban areas of the European Union and classified as a global city.

- Roman Kingdom 753–509 BC

- Roman Republic 509–27 BC

- Roman Empire 27 BC – 395 AD

- Western Roman Empire 286–476

- Kingdom of Italy 476–493

- Ostrogothic Kingdom 493–536

Eastern Roman Empire 536–546

- Ostrogothic Kingdom 546–547

Eastern Roman Empire 547–549

- Ostrogothic Kingdom 549–552

Eastern Roman Empire 552–751

- Kingdom of the Lombards 751–756

Papal States 756–1798

Roman Republic 1798–1799

Papal States 1799–1809

First French Empire 1809–1814

Papal States 1814–1849

Roman Republic 1849

Papal States 1849–1870

Kingdom of Italy 1870–1943

Italian Social Republic 1943–1944

Kingdom of Italy 1944–1946

Italian Republic 1946–present

Ancient Rome

| Rome timeline | |

|---|---|

| Roman Kingdom and Republic | |

| 753 BC | According to legend, Romulus founds Rome. |

| 753–509 BC | Rule of the seven Kings of Rome. |

| 509 BC | Creation of the Republic. |

| 390 BC | The Gauls invade Rome. Rome sacked. |

| 264–146 BC | Punic Wars. |

| 146–44 BC | Social and Civil Wars. Emergence of Marius, Sulla, Pompey and Caesar. |

| 44 BC | Julius Caesar assassinated. |

Earliest history

There is archaeological evidence of human occupation of the Rome area from at least 5,000 years, but the dense layer of much younger debris obscures Palaeolithic and Neolithic sites.[2] The evidence suggesting the city's ancient foundation is also obscured by the legend of Rome's beginning involving Romulus and Remus.

The traditional date for the founding of Rome is 21 April 753 BC, following Marcus Terentius Varro,[3] and the city and surrounding region of Latium has continued to be inhabited with little interruption since around that time. Excavations made in 2014 have revealed a wall built long before the city's official founding year. Archaeologists uncovered a stone wall and pieces of pottery dating to the 9th century BC and the beginning of the 8th century BC, and there is evidence of people arriving on the Palatine hill as early as the 10th century BC.[4][5]

The site of Sant'Omobono Area is crucial for understanding the related processes of monumentalization, urbanization, and state formation in Rome in the late Archaic period. The Sant'Omobono temple site dates to 7th–6th century BC, making these the oldest known temple remains in Rome.[6]

Legendary origin

The origin of the city's name is thought to be that of the reputed founder and first ruler, the legendary Romulus.[7] It is said that Romulus and his twin brother Remus, apparent sons of the god Mars and descendants of the Trojan hero Aeneas, were suckled by a she-wolf after being abandoned, then decided to build a city. The brothers argued, Romulus killed Remus, and then named the city Rome after himself. After founding and naming Rome (as the story goes), he permitted men of all classes to come to Rome as citizens, including slaves and freemen without distinction.[8] To provide his citizens with wives, Romulus invited the neighboring tribes to a festival in Rome where he abducted many of their young women (known as The Rape of the Sabine Women). After the ensuing war with the Sabines, Romulus shared the kingship with Sabine King Titus Tatius.[9] Romulus selected 100 of the most noble men to form the Roman senate as an advisory council to the king. These men he called patres, and their descendants became the patricians. He created three centuries of equites: Ramnes (meaning Romans), Tities (after the Sabine king), and Luceres (Etruscans). He also divided the general populace into thirty curiae, named after thirty of the Sabine women who had intervened to end the war between Romulus and Tatius. The curiae formed the voting units in the Comitia Curiata.[10]

Attempts have been made to find a linguistic root for the name Rome. Possibilities include derivation from the Greek Ῥώμη, meaning bravery, courage;[11] possibly the connection is with a root *rum-, "teat", with a theoretical reference to the totem wolf that adopted and suckled the cognately-named twins. The Etruscan name of the city seems to have been Ruma.[12] Compare also Rumon, former name of the Tiber River. Its further etymology remains unknown, as with most Etruscan words. Thomas G. Tucker's Concise Etymological Dictionary of Latin (1931) suggests that the name is most probably from *urobsma (cf. urbs, robur) and otherwise, "but less likely" from *urosma "hill" (cf. Skt. varsman- "height, point," Old Slavonic врьхъ "top, summit", Russ. верх "top; upward direction", Lith. virsus "upper").

City's formation

Rome grew from pastoral settlements on the Palatine Hill and surrounding hills approximately 30 km (19 mi) from the Tyrrhenian Sea on the south side of the Tiber. The Quirinal Hill was probably an outpost for the Sabines, another Italic-speaking people. At this location, the Tiber forms a Z-shaped curve that contains an island where the river can be forded. Because of the river and the ford, Rome was at a crossroads of traffic following the river valley and of traders traveling north and south on the west side of the peninsula.

Archaeological finds have confirmed that there were two fortified settlements in the 8th century BC, in the area of the future Rome: Rumi on the Palatine Hill, and Titientes on the Quirinal Hill, backed by the Luceres living in the nearby woods.[13] These were simply three of numerous Italic-speaking communities that existed in Latium, a plain on the Italian peninsula, by the 1st millennium BC. The origins of the Italic peoples lie in prehistory and are therefore not precisely known, but their Indo-European languages migrated from the east in the second half of the 2nd millennium BC.

According to Dionysius of Halicarnassus, many Roman historians (including Porcius Cato and Gaius Sempronius) considered the origins of the Romans (descendants of the Aborigines) as Greek despite the fact that their knowledge was derived from Greek legendary accounts.[14] The Sabines, specifically, were first mentioned in Dionysius's account for having captured the city of Lista by surprise, which was regarded as the mother-city of the Aborigines.[15]

Italic context

The Italic speakers in the area included Latins (in the west), Sabines (in the upper valley of the Tiber), Umbrians (in the north-east), Samnites (in the South), Oscans, and others. In the 8th century BC, they shared the peninsula with two other major ethnic groups: the Etruscans in the North and the Greeks in the south.

The Etruscans (Etrusci or Tusci in Latin) are attested north of Rome in Etruria (modern northern Lazio, Tuscany and part of Umbria). They founded cities such as Tarquinia, Veii, and Volterra and deeply influenced Roman culture, as clearly shown by the Etruscan origin of some of the mythical Roman kings. Historians have no literature, nor texts of religion or philosophy; therefore, much of what is known about this civilisation is derived from grave goods and tomb findings.[16]

The Greeks had founded many colonies in Southern Italy between 750 and 550 BC (which the Romans later called Magna Graecia), such as Cumae, Naples, Reggio Calabria, Crotone, Sybaris, and Taranto, as well as in the eastern two-thirds of Sicily.[17][18]

Etruscan dominance

After 650 BC, the Etruscans became dominant in Italy and expanded into north-central Italy. Roman tradition claimed that Rome had been under the control of seven kings from 753 to 509 BC beginning with the mythical Romulus who was said to have founded the city of Rome along with his brother Remus. The last three kings were said to be Etruscan (at least partially)—namely Tarquinius Priscus, Servius Tullius and Tarquinius Superbus. (Priscus is said by the ancient literary sources to be the son of a Greek refugee and an Etruscan mother.) Their names refer to the Etruscan town of Tarquinia.

Livy, Plutarch, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, and others claim that Rome was ruled during its first centuries by a succession of seven kings. The traditional chronology, as codified by Varro, allots 243 years for their reigns, an average of almost 35 years, which has been generally discounted by modern scholarship since the work of Barthold Georg Niebuhr. The Gauls destroyed much of Rome's historical records when they sacked the city after the Battle of the Allia in 390 BC (according to Polybius, the battle occurred in 387/386) and what was left was eventually lost to time or theft. With no contemporary records of the kingdom existing, all accounts of the kings must be carefully questioned.[20] The list of kings is also of dubious historical value, though the last-named kings may be historical figures. It is believed by some historians (again, this is disputed) that Rome was under the influence of the Etruscans for about a century. During this period, a bridge was built called the Pons Sublicius to replace the Tiber ford, and the Cloaca Maxima was also built; the Etruscans are said to have been great engineers of this type of structure. From a cultural and technical point of view, Etruscans had arguably the second-greatest impact on Roman development, only surpassed by the Greeks.

Expanding further south, the Etruscans came into direct contact with the Greeks and initially had success in conflicts with the Greek colonists; after which, Etruria went into a decline. Taking advantage of this, Rome rebelled and gained independence from the Etruscans around 500 BC. It also abandoned monarchy in favour of a republican system based on a Senate, composed of the nobles of the city, along with popular assemblies which ensured political participation for most of the freeborn men and elected magistrates annually.

The Etruscans left a lasting influence on Rome. The Romans learned to build temples from them, and the Etruscans may have introduced the worship of a triad of gods—Juno, Minerva, and Jupiter—from the Etruscan gods: Uni, Menrva, and Tinia. However, the influence of Etruscan people in the development of Rome is often overstated.[21] Rome was primarily a Latin city. It never became fully Etruscan. Also, evidence shows that Romans were heavily influenced by the Greek cities in the South, mainly through trade.[22]

Roman Republic

The commonly held stories of the early part of the Republic (before roughly 300 BC, when Old Latin inscriptions and Greek histories about Rome provide more concrete evidence of events) are generally considered to be legendary, their historicity being a topic of debate among classicists. The Roman Republic traditionally dates from 509 BC to 27 BC. After 500 BC, Rome is said to have joined with the Latin cities in defence against incursions by the Sabines. Winning the Battle of Lake Regillus in 493 BC, Rome established again the supremacy over the Latin countries it had lost after the fall of the monarchy. After a lengthy series of struggles, this supremacy became fixed in 393, when the Romans finally subdued the Volsci and Aequi. In 394 BC, they also conquered the menacing Etruscan neighbour of Veii. The Etruscan power was now limited to Etruria itself, and Rome was the dominant city in Latium.

A formal treaty was agreed with the city-state of Carthage in 509 BC which defined the spheres of influence of each city and regulated trade between them.[23]

At the same time, Heraclides stated that 4th-century Rome was a Greek city (Plut. Cam. 22).

Rome's early enemies were the neighbouring hill tribes of the Volscians, the Aequi, and of course the Etruscans. As years passed and military successes increased Roman territory, new adversaries appeared. The fiercest were the Gauls, a loose collective of peoples who controlled much of Northern Europe including what is modern North and Central-East Italy.

In 387 BC, Rome was sacked and burned by the Senones coming from eastern Italy and led by Brennus, who had successfully defeated the Roman army at the Battle of the Allia in Etruria. Multiple contemporary records suggest that the Senones hoped to punish Rome for violating its diplomatic neutrality in Etruria. The Senones marched 130 kilometres (81 mi) to Rome without harming the surrounding countryside; once they had sacked the city, the Senones withdrew from Rome.[24] Brennus was defeated by the dictator Furius Camillus at Tusculum soon afterwards.[25][26]

After that, Rome hastily rebuilt its buildings and went on the offensive, conquering the Etruscans and seizing territory from the Gauls in the north. After 345 BC, Rome pushed south against other Latins. Their main enemy in this quadrant were the fierce Samnites, who outsmarted and trapped the legions in 321 BC at the Battle of Caudine Forks. In spite of these and other temporary setbacks, the Romans advanced steadily. By 290 BC, Rome controlled over half of the Italian peninsula. In the 3rd century BC, Rome brought the Greek poleis in the south under its control as well.

Amidst the never-ending wars (from the beginning of the Republic up to the Principate, the doors of the temple of Janus were closed only twice—when they were open it meant that Rome was at war), Rome had to face a severe major social crisis, the Conflict of the Orders, a political struggle between the Plebeians (commoners) and Patricians (aristocrats) of the ancient Roman Republic, in which the Plebeians sought political equality with the Patricians. It played a major role in the development of the Constitution of the Roman Republic. It began in 494 BC, when, while Rome was at war with two neighboring tribes, the Plebeians all left the city (the first Plebeian Secession). The result of this first secession was the creation of the office of Plebeian Tribune, and with it the first acquisition of real power by the Plebeians.[27]

According to tradition, Rome became a republic in 509 BC. However, it took a few centuries for Rome to become the great city of popular imagination. By the 3rd century BC, Rome had become the pre-eminent city of the Italian peninsula. During the Punic Wars between Rome and the great Mediterranean empire of Carthage (264–146 BC), Rome's stature increased further as it became the capital of an overseas empire for the first time. Beginning in the 2nd century BC, Rome went through a significant population expansion as Italian farmers, driven from their ancestral farmlands by the advent of massive, slave-operated farms called latifundia, flocked to the city in great numbers. The victory over Carthage in the First Punic War brought the first two provinces outside the Italian peninsula, Sicily and Sardinia.[28] Parts of Spain (Hispania) followed, and in the beginning of the 2nd century the Romans got involved in the affairs of the Greek world. By then all Hellenistic kingdoms and the Greek city-states were in decline, exhausted from endless civil wars and relying on mercenary troops.

The Romans looked upon the Greek civilisation with great admiration. The Greeks saw Rome as a useful ally in their civil strifes, and it was not long before the Roman legions were invited to intervene in Greece. In less than 50 years the whole of mainland Greece was subdued. The Roman legions crushed the Macedonian phalanx twice, in 197 and 168 BC; in 146 BC the Roman consul Lucius Mummius razed Corinth, marking the end of free Greece. The same year Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus, the son of Scipio Africanus, destroyed the city of Carthage, making it a Roman province.

In the following years, Rome continued its conquests in Spain with Tiberius Gracchus, and it set foot in Asia, when the last king of Pergamum gave his kingdom to the Roman people. The end of the 2nd century brought another threat, when a great host of Germanic peoples, namely Cimbri and Teutones, crossed the river Rhone and moved to Italy. Gaius Marius was consul five consecutive times (seven total), and won two decisive battles in 102 and 101 BC. He also reformed the Roman army, giving it such a good reorganization that it remained unchanged for centuries.

The first thirty years of the last century BC were characterised by serious internal problems that threatened the existence of the Republic. The Social War, between Rome and its allies, and the Servile Wars (slave uprisings) were hard conflicts,[29] all within Italy, and forced the Romans to change their policy with regards to their allies and subjects.[30] By then Rome had become an extensive power, with great wealth which derived from the conquered people (as tribute, food or manpower, i.e. slaves). The allies of Rome felt bitter since they had fought by the side of the Romans, and yet they were not citizens and shared little in the rewards. Although they lost the war, they finally got what they asked, and by the beginning of the 1st century AD practically all free inhabitants of Italy were Roman citizens.

However, the growth of the Imperium Romanum (Roman power) created new problems, and new demands, that the old political system of the Republic, with its annually elected magistrates and its sharing of power, could not solve. The dictatorship of Sulla, the extraordinary commands of Pompey Magnus, and the first triumvirate made that clear. In January 49 BC, Julius Caesar the conqueror of Gaul, marched his legions against Rome. In the following years, he vanquished his opponents, and ruled Rome for four years. After his assassination in 44 BC, the Senate tried to reestablish the Republic, but its champions, Marcus Junius Brutus (descendant of the founder of the republic) and Gaius Cassius Longinus were defeated by Caesar's lieutenant Marcus Antonius and Caesar's nephew, Octavian.

The years 44–31 BC mark the struggle for power between Marcus Antonius and Octavian (later known as Augustus). Finally, on 2 September 31 BC, in the Greek promontory of Actium, the final battle took place in the sea. Octavian was victorious, and became the sole ruler of Rome (and its empire). That date marks the end of the Republic and the beginning of the Principate.[31][32]

Roman Empire

| Rome timeline | |

|---|---|

| Roman Empire | |

| 44 BC – 14 AD | Augustus establishes the Empire |

| 64 AD | Great Fire of Rome during Nero's rule |

| 69–96 | Flavian dynasty; building of the Colosseum |

| 3rd century | Crisis of the Third Century; building of the Baths of Caracalla and the Aurelian Walls |

| 284–337 | Diocletian and Constantine; building of the first Christian basilicas; Battle of Milvian Bridge; Rome is replaced by Constantinople as the capital of the Empire |

| 395 | Definitive separation of Western and Eastern Roman Empire |

| 410 | The Goths of Alaric sack Rome |

| 455 | The Vandals of Gaiseric sack Rome |

| 476 | Fall of the west empire and deposition of the final emperor Romulus Augustus |

| 6th century | Gothic War (535–554): The Goths cut off the aqueducts in the siege of 537, an act which historians traditionally regard as the beginning of the Middle Ages in Italy[33] |

| 608 | Emperor Phocas donates the Pantheon to Pope Boniface IV, converting it into a Christian church; Column of Phocas (the last addition made to the Forum Romanum) is erected |

| 630 | The Curia Julia (vacant since the disappearance of the Roman Senate) is transformed into the basilica of Sant'Adriano al Foro |

| 663 | Constans II visits Rome for twelve days—the only emperor to set foot in Rome for two centuries. He strips buildings of their ornaments and bronze to be carried back to Constantinople |

| 751 | Lombard conquest of the Exarchate of Ravenna; the Duchy of Rome is now completely cut off from the empire |

| 754 | Alliance with the Franks; Pepin the Younger, King of the Franks, declared Patrician of the Romans, invades Italy; establishment of the Papal States |

Early Empire

By the end of the Republic, the city of Rome had achieved a grandeur befitting the capital of an empire dominating the whole of the Mediterranean. It was, at the time, the largest city in the world. Estimates of its peak population range from 450,000 to over 3.5 million people with estimates of 1 to 2 million being most popular with historians.[34] This grandeur increased under Augustus, who completed Caesar's projects and added many of his own, such as the Forum of Augustus and the Ara Pacis. He is said to have remarked that he found Rome a city of brick and left it a city of marble (Urbem latericium invenit, marmoream reliquit). Augustus's successors sought to emulate his success in part by adding their own contributions to the city. In 64 AD, during the reign of Nero, the Great Fire of Rome left much of the city destroyed, but in many ways it was used as an excuse for new development.[35][36]

Rome was a subsidised city at the time, with roughly 15 to 25 percent of its grain supply being paid by the central government. Commerce and industry played a smaller role compared to that of other cities like Alexandria. This meant that Rome had to depend upon goods and production from other parts of the Empire to sustain such a large population. This was mostly paid by taxes that were levied by the Roman government. If it had not been subsidised, Rome would have been significantly smaller.[37]

Rome's population declined after its apex in the 2nd century. At the end of that century, during the reign of Marcus Aurelius, the Antonine Plague killed 2,000 people a day.[38] Marcus Aurelius died in 180, his reign being the last of the "Five Good Emperors" and Pax Romana. His son Commodus, who had been co-emperor since 177 AD, assumed full imperial power, which is generally associated with the beginning of the decline of the Western Roman Empire. Rome's population was only a fraction of its peak when the Aurelian Wall was completed in 273 AD (in that year its population was only around 500,000).

Crisis of the third century

Starting in the early 3rd century, matters changed. The "Crisis of the Third Century" defines the disasters and political troubles for the Empire, which nearly collapsed. The new feeling of danger and the menace of barbarian invasions was clearly shown by the decision of Emperor Aurelian, who at year 273 finished encircling the capital itself with a massive wall which had a perimeter that measured close to 20 km (12 mi). Rome formally remained capital of the empire, but emperors spent less and less time there. At the end of 3rd century Diocletian's political reforms, Rome was deprived of its traditional role of administrative capital of the Empire. Later, western emperors ruled from Milan or Ravenna, or cities in Gaul. In 330, Constantine I established a second capital at Constantinople.

Christianization

Christianity reached Rome during the 1st century AD. For the first two centuries of the Christian era, Imperial authorities largely viewed Christianity simply as a Jewish sect rather than a distinct religion. No emperor issued general laws against the faith or its Church, and persecutions, such as they were, were carried out under the authority of local government officials.[39] A surviving letter from Pliny the Younger, governor of Bythinia, to the emperor Trajan describes his persecution and executions of Christians; Trajan notably responded that Pliny should not seek out Christians nor heed anonymous denunciations, but only punish open Christians who refused to recant.[40]

Suetonius mentions in passing that during the reign of Nero "punishment was inflicted on the Christians, a class of men given to a new and mischievous superstition" (superstitionis novae ac maleficae).[41] He gives no reason for the punishment. Tacitus reports that after the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD, some among the population held Nero responsible and that the emperor attempted to deflect blame onto the Christians.[42] The war against the Jews during Nero's reign, which so destabilised the empire that it led to civil war and Nero's suicide, provided an additional rationale for suppression of this 'Jewish' sect.

Diocletian undertook what was to be the most severe and last major persecution of Christians, lasting from 303 to 311. Christianity had become too widespread to suppress, and in 313, the Edict of Milan made tolerance the official policy. Constantine I (sole ruler 324–337) became the first Christian emperor, and in 380 Theodosius I established Christianity as the official religion.

Under Theodosius, visits to the pagan temples were forbidden,[43] the eternal fire in the Temple of Vesta in the Roman Forum extinguished, the Vestal Virgins disbanded, auspices and witchcraft punished. Theodosius refused to restore the Altar of Victory in the Senate House, as asked by remaining pagan Senators.

The Empire's conversion to Christianity made the Bishop of Rome (later called the Pope) the senior religious figure in the Western Empire, as officially stated in 380 by the Edict of Thessalonica. In spite of its increasingly marginal role in the Empire, Rome retained its historic prestige, and this period saw the last wave of construction activity: Constantine's predecessor Maxentius built buildings such as its basilica in the Forum, Constantine himself erected the Arch of Constantine to celebrate his victory over Maxentius, and Diocletian built the greatest baths of all. Constantine was also the first patron of official Christian buildings in the city. He donated the Lateran Palace to the Pope, and built the first great basilica, the old St. Peter's Basilica.

Germanic invasions and collapse of the Western Empire

Still Rome remained one of the strongholds of paganism, led by the aristocrats and senators. However, the new walls did not stop the city being sacked first by Alaric on 24 August 410, by Geiseric on 2 June 455, and even by general Ricimer's unpaid Roman troops (largely composed of barbarians) on 11 July 472.[44][45] This was the first time in almost 800 years that Rome had fallen to an enemy. The previous sack of Rome had been accomplished by the Gauls under their leader Brennus in 387 BC. The sacking of 410 is seen as a major landmark in the decline and fall of the Western Roman Empire. St. Jerome, living in Bethlehem at the time, wrote that "The City which had taken the whole world was itself taken."[46] These sackings of the city astonished all the Roman world. In any case, the damage caused by the sackings may have been overestimated. The population already started to decline from the late 4th century onward, although around the middle of the fifth century it seems that Rome continued to be the most populous city of the two parts of the Empire, with a population of no fewer than 650,000 inhabitants.[47] The decline greatly accelerated following the capture of Africa Proconsularis by the Vandals. Many inhabitants now fled as the city no longer could be supplied with grain from Africa from the mid-5th century onward.

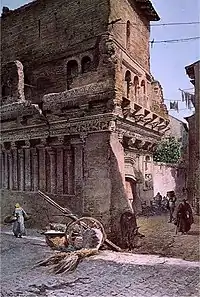

At the end of the 6th century Rome's population had reduced to around 30,000.[48] Many monuments were being destroyed by the citizens themselves, who stripped stones from closed temples and other precious buildings, and even burned statues to make lime for their personal use. In addition, most of the increasing number of churches were built in this way. For example, the first Saint Peter's Basilica was erected using spoils from the abandoned Circus of Nero.[49] This architectural cannibalism was a constant feature of Roman life until the Renaissance. From the 4th century, imperial edicts against stripping of stones and especially marble were common, but the need for their repetition shows that they were ineffective. Sometimes new churches were created by simply taking advantage of early Pagan temples, while sometimes changing the Pagan god or hero to a corresponding Christian saint or martyr. In this way, the Temple of Romulus and Remus became the basilica of the twin saints Cosmas and Damian. Later, the Pantheon, Temple of All Gods, became the church of All Martyrs.

Eastern Roman (Byzantine) restoration

In 480, the last Western Roman emperor, Julius Nepos, was murdered and a Roman general of barbarian origin, Odoacer, declared allegiance to Eastern Roman emperor Zeno.[50] Despite owing nominal allegiance to Constantinople, Odoacer and later the Ostrogoths continued, like the last emperors, to rule Italy as a virtually independent realm from Ravenna. Meanwhile, the Senate, even though long since stripped of wider powers, continued to administer Rome itself, with the Pope usually coming from a senatorial family. This situation continued until Theodahad murdered Amalasuntha, a pro-imperial Gothic queen, and usurped the power in 535. The Eastern Roman emperor, Justinian I (reigned 527–565), used this as a pretext to send forces to Italy under his famed general Belisarius, recapturing the city next year, on 9 December 536 AD. In 537–538, the Eastern Romans successfully defended the city in a year-long siege against the Ostrogothic army, and eventually took Ravenna, too.[50]

Gothic resistance revived however, and on 17 December 546, the Ostrogoths under Totila recaptured and sacked Rome.[51] Belisarius soon recovered the city, but the Ostrogoths retook it in 549. Belisarius was replaced by Narses, who captured Rome from the Ostrogoths for good in 552, ending the so-called Gothic Wars which had devastated much of Italy. The continual war around Rome in the 530s and 540s left it in a state of total disrepair – near-abandoned and desolate with much of its lower-lying parts turned into unhealthy marshes as the drainage systems were neglected and the Tiber's embankments fell into disrepair in the course of the latter half of the 6th century.[52] Here, malaria developed. The aqueducts, except for one, were not repaired. The population, without imports of grain and oil from Sicily, shrank to less than 50,000 concentrated near the Tiber and around the Campus Martius, abandoning those districts without water supply. There is a legend, significant though untrue, that there was a moment where no one remained living in Rome.

Justinian I provided grants for the maintenance of public buildings, aqueducts and bridges—though, being mostly drawn from an Italy dramatically impoverished by the recent wars, these were not always sufficient. He also styled himself the patron of its remaining scholars, orators, physicians and lawyers in the stated hope that eventually more youths would seek a better education. After the wars, the Senate was theoretically restored, but under the supervision of the urban prefect and other officials appointed by, and responsible to, the Eastern Roman authorities in Ravenna.

However, the Pope was now one of the leading religious figures in the entire Byzantine Roman Empire and effectively more powerful locally than either the remaining senators or local Eastern Roman (Byzantine) officials. In practice, local power in Rome devolved to the Pope and, over the next few decades, both much of the remaining possessions of the senatorial aristocracy and the local Byzantine Roman administration in Rome were absorbed by the Church.

The reign of Justinian's nephew and successor Justin II (reigned 565–578) was marked from the Italian point of view by the invasion of the Lombards under Alboin (568). In capturing the regions of Benevento, Lombardy, Piedmont, Spoleto and Tuscany, the invaders effectively restricted Imperial authority to small islands of land surrounding a number of coastal cities, including Ravenna, Naples, Rome and the area of the future Venice. The one inland city continuing under Eastern Roman control was Perugia, which provided a repeatedly threatened overland link between Rome and Ravenna. In 578 and again in 580, the Senate, in some of its last recorded acts, had to ask for the support of Tiberius II Constantine (reigned 578–582) against the approaching Dukes, Faroald I of Spoleto and Zotto of Benevento.

Maurice (reigned 582–602) added a new factor in the continuing conflict by creating an alliance with Childebert II of Austrasia (reigned 575–595). The armies of the Frankish King invaded the Lombard territories in 584, 585, 588 and 590. Rome had suffered badly from a disastrous flood of the Tiber in 589, followed by a plague in 590. The latter is notable for the legend of the angel seen, while the newly elected Pope Gregory I (term 590–604) was passing in procession by Hadrian's Tomb, to hover over the building and to sheathe his flaming sword as a sign that the pestilence was about to cease. The city was safe from capture at least.

Agilulf, however, the new Lombard King (reigned 591 to c. 616), managed to secure peace with Childebert, reorganised his territories and resumed activities against both Naples and Rome by 592. With the Emperor preoccupied with wars in the eastern borders and the various succeeding Exarchs unable to secure Rome from invasion, Gregory took personal initiative in starting negotiations for a peace treaty. This was completed in the autumn of 598—later recognised by Maurice—lasting until the end of his reign.

The position of the Bishop of Rome was further strengthened under the usurper Phocas (reigned 602–610). Phocas recognised his primacy over that of the Patriarch of Constantinople and even decreed Pope Boniface III (607) to be "the head of all the Churches". Phocas's reign saw the erection of the last imperial monument in the Roman Forum, the column bearing his name. He also gave the Pope the Pantheon, at the time closed for centuries, and thus probably saved it from destruction.

During the 7th century, an influx of both Byzantine Roman officials and churchmen from elsewhere in the empire made both the local lay aristocracy and Church leadership largely Greek speaking. The population of Rome, a magnet for pilgrims, may have increased to 90,000.[53] Eleven of thirteen popes between 678 and 752 were of Greek or Syrian descent.[54] However, the strong Byzantine Roman cultural influence did not always lead to political harmony between Rome and Constantinople. In the controversy over Monothelitism, popes found themselves under severe pressure (sometimes amounting to physical force) when they failed to keep in step with Constantinople's shifting theological positions. In 653, Pope Martin I was deported to Constantinople and, after a show trial, exiled to the Crimea, where he died.[55][56]

Then, in 663, Rome had its first imperial visit for two centuries, by Constans II—its worst disaster since the Gothic Wars when the Emperor proceeded to strip Rome of metal, including that from buildings and statues, to provide armament materials for use against the Saracens. However, for the next half century, despite further tensions, Rome and the Papacy continued to prefer continued Byzantine Roman rule: in part because the alternative was Lombard rule, and in part because Rome's food was largely coming from Papal estates elsewhere in the Empire, particularly Sicily.

Medieval Rome

| Rome Timeline | |

|---|---|

| Medieval Rome | |

| 772 | The Lombards briefly conquer Rome but Charlemagne liberates the city a year later. |

| 800 | Charlemagne is crowned Holy Roman Emperor in St. Peter's Basilica. |

| 846 | The Saracens sack St. Peter. |

| 852 | Building of the Leonine Walls. |

| 962 | Otto I crowned Emperor by Pope John XII |

| 1000 | Emperor Otto III and Pope Sylvester II. |

| 1084 | The Normans sack Rome. |

| 1144 | Creation of the commune of Rome. |

| 1300 | First Jubilee proclaimed by Pope Boniface VIII. |

| 1303 | Foundation of the Roman University. |

| 1309 | Pope Clement V moves the Holy Seat to Avignon. |

| 1347 | Cola di Rienzo proclaims himself tribune. |

| 1377 | Pope Gregory XI moves the Holy Seat back to Rome. |

Break with Constantinople and formation of the Papal States

In 727, Pope Gregory II refused to accept the decrees of Emperor Leo III, which promoted the Emperor's iconoclasm.[57] Leo reacted first by trying in vain to abduct the Pontiff, and then by sending a force of Ravennate troops under the command of the Exarch Paulus, but they were pushed back by the Lombards of Tuscia and Benevento. Byzantine general Eutychius sent west by the Emperor successfully captured Rome and restored it as a part of the empire in 728.

On 1 November 731, a council was called in St. Peter's by Gregory III to excommunicate the iconoclasts. The Emperor responded by confiscating large Papal estates in Sicily and Calabria and transferring areas previously ecclesiastically under the Pope to the Patriarch of Constantinople. Despite the tensions Gregory III never discontinued his support to the imperial efforts against external threats.

In this period the Lombard kingdom revived under the leadership of King Liutprand. In 730, he razed the countryside of Rome to punish the Pope, who had supported Duke Transamund II of Spoleto.[58] Though still protected by his massive walls, the Pope could do little against the Lombard king, who managed to ally himself with the Byzantines.[59] Other protectors were now needed. Gregory III was the first Pope to ask for concrete help from the Frankish Kingdom, then under the command of Charles Martel (739).[60]

Liutprand's successor Aistulf was even more aggressive. He conquered Ferrara and Ravenna, ending the Exarchate of Ravenna. Rome seemed his next victim. In 754, Pope Stephen II went to France to name Pippin the Younger, king of the Franks, as patricius Romanorum, i.e. protector of Rome. In the August of that year the King and Pope together crossed back the Alps and defeated Aistulf at Pavia. When Pippin went back to St. Denis however, Aistulf did not keep his promises, and in 756 besieged Rome for 56 days. The Lombards returned north when they heard news of Pippin again moving to Italy. This time he agreed to give the Pope the promised territories, and the Papal States were born.

In 771 the new King of the Lombards, Desiderius, devised a plot to conquer Rome and seize Pope Stephen III during a feigned pilgrimage within its walls. His main ally was one Paulus Afiarta, chief of the Lombard party within the city. He conquered Rome in 772 but angered Charlemagne. However the plan failed, and Stephen's successor, Pope Hadrian I called Charlemagne against Desiderius, who was finally defeated in 773.[61] The Lombard Kingdom was no more, and now Rome entered into the orbit of a new, greater political institution.

Numerous remains from this period, along with a museum devoted to Medieval Rome, can be seen at Crypta Balbi in Rome.

Formation of the Holy Roman Empire

On 25 April 799 the new Pope, Leo III, led the traditional procession from the Lateran to the Church of San Lorenzo in Lucina along the Via Flaminia (now Via del Corso). Two nobles (followers of his predecessor Hadrian) who disliked the weakness of the Pope with regards to Charlemagne, attacked the processional train and delivered a life-threatening wound to the Pope. Leo fled to the King of the Franks, and in November, 800, the King entered Rome with a strong army and a number of French bishops. He declared a judicial trial to decide if Leo III were to remain Pope, or if the deposers' claims had reasons to be upheld. This trial, however, was only a part of a well thought out chain of events which ultimately surprised the world. The Pope was declared legitimate and the attempters subsequently exiled. On 25 December 800, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne Holy Roman Emperor in St. Peter's Basilica.

This act forever severed the loyalty of Rome from its imperial progenitor, Constantinople. It created instead a rival empire which, after a long series of conquests by Charlemagne, now encompassed most of the Christian Western territories.

Following the death of Charlemagne, the lack of a figure with equal prestige led the new institution into disagreement. At the same time the universal church of Rome had to face emergence of the lay interests of the City itself, spurred on by the conviction that the Roman people, though impoverished and abased, had again the right to elect the Western Emperor. The famous counterfeit document called the Donation of Constantine, prepared by the Papal notaries, guaranteed to the Pope a dominion[62][63] stretching from Ravenna to Gaeta. This nominally included the suzerainty over Rome, but this was often highly disputed, and as the centuries passed, only the strongest Popes were to be able to assert it. The main element of weakness of the Papacy within the walls of the city was the continued necessity of the election of new popes, in which the emerging noble families soon managed to insert a leading role for themselves. The neighbouring powers, namely the Duchy of Spoleto and Toscana, and later the Emperors, learned how to take their own advantage of this internal weakness, playing the role of arbiters among the contestants.

Rome was indeed prey of anarchy in this age. The lowest point was touched in 897, when a raging crowd exhumed the corpse of a dead pope, Formosus, and put it on trial.[64][65][66][67]

Roman Commune

From 1048 to 1257, the papacy experienced increasing conflict with the leaders and churches of the Holy Roman Empire and the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire. The latter culminated in the East-West Schism, dividing the Catholic Church and Eastern Orthodox Church. From 1257 to 1377, the pope, though the bishop of Rome, resided in Viterbo, Orvieto, and Perugia, and then Avignon. The return of the popes to Rome after the Avignon Papacy was followed by the Western Schism: the division of the western church between two, and for a time three, competing papal claimants.

In this period the renovated Church was again attracting pilgrims and prelates from all the Christian world, and money with them: even with a population of only 30,000, Rome was again becoming a city of consumers dependent upon the presence of a governmental bureaucracy. In the meantime, Italian cities were acquiring increasing autonomy, mainly led by new families which were replacing the old aristocracy with a new class formed by entrepreneurs, traders and merchants. After the sack of Rome by the Normans in 1084, the rebuilding of the city was supported by powerful families such as the Frangipane family and the Pierleoni family, whose wealth came from commerce and banking rather than landholdings. Inspired by neighbouring cities like Tivoli and Viterbo, Rome's people began to consider adopting a communal status and gaining a substantial amount of freedom from papal authority.

Led by Giordano Pierleoni, the Romans rebelled against the aristocracy and Church rule in 1143. The Senate and the Roman Republic, the Commune of Rome, were born again. Through the inflammatory words of preacher Arnaldo da Brescia, an idealistic, fierce opponent of ecclesiastical property and church interference in temporal affairs, the revolt that led to the creation of the Commune of Rome continued until it was put down in 1155, though it left its mark on the civil government of the Eternal City for centuries. 12th-century Rome, however, had little in common with the empire which had ruled over the Mediterranean some 700 years before, and soon the new Senate had to work hard to survive, choosing an ambiguous policy of shifting its support from the Pope to the Holy Roman Empire and vice versa as the political situation required. At Monteporzio, in 1167, during one of these shifts, in the war with Tusculum, Roman troops were defeated by the imperial forces of Frederick Barbarossa. Luckily, the winning enemies were soon dispersed by a plague and Rome was saved.

In 1188 the new communal government was finally recognised by Pope Clement III. The Pope had to make large cash payments to the communal officials, while the 56 senators became papal vassals. The Senate always had problems in the accomplishment of its function, and various changes were tried. Often a single Senator was in charge. This sometimes led to tyrannies, which did not help the stability of the newborn organism.

Guelphs and Ghibellines

In 1204 the streets of Rome were again in flames when the struggle between Pope Innocent III's family and its rivals, the powerful Orsini family, led to riots in the city. Many ancient buildings were then destroyed by machines used by the rival bands to besiege their enemies in the innumerable towers and strongholds which were a hallmark of the Middle Age Italian towns.

The struggle between the Popes and the emperor Frederick II, also king of Naples and Sicily, saw Rome support the Ghibellines. To repay his loyalty, Frederick sent to the commune the Carroccio he had won to the Lombards at the battle of Cortenuova in 1234, and which was exposed in the Campidoglio.

In that year, during another revolt against the Pope, the Romans headed by senator Luca Savelli sacked the Lateran. Savelli was the father of Honorius IV, but in that age family ties often did not determine one's allegiance.

Rome was never to evolve into an autonomous, stable reign, as happened to other communes like Florence, Siena or Milan. The endless struggles between noble families (Savelli, Orsini, Colonna, Annibaldi), the ambiguous position of the Popes, the haughtiness of a population which never abandoned the dreams of their splendid past but, at the same time, thought only of immediate advantage, and the weakness of the republican institutions always deprived the city of this possibility.

In an attempt to imitate more successful communes, in 1252 the people elected a foreign Senator, the Bolognese Brancaleone degli Andalò. In order to bring peace in the city he suppressed the most powerful nobles (destroying some 140 towers), reorganised the working classes and issued a code of laws inspired by those of northern Italy. Brancaleone was a tough figure, but died in 1258 with almost nothing of his reforms turned into reality. Five years later Charles I of Anjou, then king of Naples, was elected Senator. He entered the city only in 1265, but soon his presence was needed to face Conradin, the Hohenstaufen's heir who was coming to claim his family's rights over southern Italy, and left the city. After June 1265 Rome was again a democratic republic, electing Henry of Castile as senator. But Conradin and the Ghibelline party were crushed in the Battle of Tagliacozzo (1268), and therefore Rome fell again in the hands of Charles.

Nicholas III, a member of Orsini family, was elected in 1277 and moved the seat of the Popes from the Lateran to the more defensible Vatican. He also ordered that no foreigner could become senator of Rome. Being a Roman himself, he had himself elected senator by the people. With this move, the city began again to side for the papal party. In 1285 Charles was again Senator, but the Sicilian Vespers reduced his charisma, and the city was thenceforth free from his authority. The next senator was again a Roman, and again a pope, Honorius IV of the Savelli.

Boniface VIII and the Avignon captivity

The successor to Celestine V was a Roman of the Caetani family, Boniface VIII. Entangled in a local feud against the traditional rivals of his family, the Colonna, at the same time he struggled to assure the universal supremacy of the Holy See. In 1300 he launched the first Jubilee and in 1303 founded the first University of Rome.[68][69] The Jubilee was an important move for Rome, as it further increased its international prestige and, most of all, the city's economy was boosted by the flow of pilgrims.[69] Boniface died in 1303 after the humiliation of the Schiaffo di Anagni ("Slap of Anagni"), which signalled instead the rule of the King of France over the Papacy and marked another period of decline for Rome.[69][70]

Boniface's successor, Clement V, never entered the city, starting the so-called "Avignon captivity", the absence of the Popes from their Roman seat in favour of Avignon, which would last for more than 70 years.[70][71] This situation brought the independence of the local powers, but these were revealed to be largely unstable; and the lack of the holy revenues caused a deep decay of Rome.[70][71] For more than a century Rome had no new major buildings. Furthermore, many of the monuments of the city, including the main churches, began to fall into ruin.[70]

Cola di Rienzo and the Pope's return to Rome

In spite of its decline and the absence of the Pope, Rome had not lost its spiritual prestige: in 1341 the famous poet Petrarca came to the city to be crowned as Poet laureate in Capitoline Hill. Noblemen and poor people at one time demanded with one voice the return of the Pope. Among the many ambassadors that in this period took their way to Avignon, emerged the bizarre but eloquent figure of Cola di Rienzo. As his personal power among the people increased by time, on 20 May 1347 he conquered the Capitoline at the head of an enthusiastic crowd. The period of his power, though very short-lived, aspired to the prestige of Ancient Rome. Now in possession of dictatorial powers, he took the title of "tribune", referring to the pleb's magistracy of the Roman Republic. Cola also considered himself at an equal status of that of the Holy Roman Emperor. On 1 August, he conferred Roman citizenship on all the Italian cities, and even prepared for the election of a Roman emperor of Italy. It was too much: the Pope denounced him as heretic, criminal and pagan, the populace had begun to be disenchanted with him, while the nobles had always hated him. On 15 December, he was forced to flee.

In August 1354, Cola was again a protagonist, when Cardinal Gil Alvarez De Albornoz entrusted him with the role of "senator of Rome" in his program of reassuring the Pope's rule in the Papal States. In October the tyrannical Cola, who had become again very unpopular for his delirious behaviour and heavy bills, was killed in a riot provoked by the powerful family of the Colonna. In April 1355, Charles IV of Bohemia entered the city for the ritual coronation as Emperor. His visit was very disappointing for the citizens. He had little money, received the crown not from the Pope but from a Cardinal, and moved away after a few days.

With the emperor back in his lands, Albornoz could regain a certain control over the city, while remaining in his safe citadel in Montefiascone, in the Northern Lazio. The senators were chosen directly by the Pope from several cities of Italy, but the city was in fact independent. The Senate council included six judges, five notaries, six marshals, several familiars, twenty knights and twenty armed men. Albornoz had heavily suppressed the traditional aristocratic families, and the "democratic" party felt confident enough to start an aggressive policy. In 1362 Rome declared war on Velletri. This move, however, provoked a civil war. The countryside party hired a condottieri band called "Del Cappello" ("Hat"), while the Romans bought the services of German and Hungarian troops, plus a citizen levy of 600 knights and even 22,000 infantry. This was the period in which condottieri bands were active in Italy. Many of the Savelli, Orsini and Annibaldi expelled from Rome became leaders of such military units. The war with Velletri languished, and Rome again gave itself to the new Pope, Urban V, provided Albornoz did not enter the walls.

On 16 October 1367, in reply to the prayers of St Brigid and Petrarca, Urban finally visited for the city. During his presence, Charles IV was again crowned in the city (October 1368). In addition, the Byzantine emperor John V Palaeologus came in Rome to beg for a crusade against the Ottoman Empire, but in vain. However, Urban did not like the unhealthy air of the city, and on 5 September 1370 he sailed again to Avignon. His successor, Gregory XI, officially set the date of his return to Rome at May 1372, but again the French cardinals and the King stopped him.

Only on 17 January 1377, Gregory XI could finally reinstate the Holy See in Rome.

Western schism and conflict with Milan

The incoherent behaviour of his successor, the Italian Urban VI, provoked in 1378 the Western Schism, which impeded any true attempt of improving the conditions of the decaying Rome. The 14th century, with the absence of the popes during the Avignon Papacy, had been a century of neglect and misery for the city of Rome, which dropped to its lowest level of population. With the return of the papacy to Rome repeatedly postponed because of the bad conditions of the city and the lack of control and security, it was first necessary to strengthen the political and doctrinal aspects of the pontiff.

When in 1377 Gregory XI was in fact returned to Rome, he found a city in anarchy because of the struggles between the nobility and the popular faction, and in which his power was now more formal than real. There followed four decades of instability, characterised by the local power struggle between the commune and the papacy, and internationally by the great Western Schism, at the end of which was elected Pope, Martin V. He restored order, laying the foundations of its rebirth.[72]

In 1433 the Duke of Milan, Filippo Maria Visconti signed a peace treaty with Florence and Venice. He then sent the condottieri Niccolò Fortebraccio and Francesco Sforza to harass the Papal States, in vengeance for Eugene IV's support to the two former republics.

Fortebraccio, supported by the Colonna, occupied Tivoli in October 1433 and ravaged Rome's countryside. Despite the concessions made by Eugene to the Visconti, the Milanese soldiers did not stop their destruction. This led the Romans, on 29 May 1434 to institute a Republican government under the Banderesi. Eugene left the city a few days later, during the night of 4 June.

However, the Banderesi proved incapable of governing the city, and their inadequacies and violence soon deprived them of popular support. The city was therefore returned to Eugene by the army of Giovanni Vitelleschi on 26 October 1434. After the death in mysterious circumstances of Vitelleschi, the city came under the control of Ludovico Scarampo, Patriarch of Aquileia. Eugene returned to Rome on 28 September 1443.

Renaissance Rome

| Rome Timeline | |

|---|---|

| Renaissance and early modern Rome | |

| c. 1420s–1519 | Rome becomes a centre of the Renaissance. Founding of the new St. Peter's Basilica. Sistine Chapel. |

| 1527 | The Landsknechts sack Rome. |

| 1555 | Creation of the Ghetto. |

| 1585–1590 | Urban reforms under Pope Sixtus V. |

| 1592–1606 | Caravaggio working in Rome. |

| 1600 | Giordano Bruno is burned. |

| 1626 | The new St. Peter's Basilica is consecrated. |

| 1638–1667 | Baroque era. Bernini and Borromini. Rome has 120,000 inhabitants. |

| 1703 | Building of the Port of Ripetta. |

| 1732–1762 | Building of the Fontana di Trevi. |

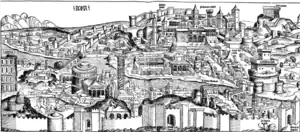

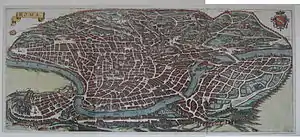

The latter half of the 15th century saw the seat of the Italian Renaissance move to Rome from Florence. The Papacy wanted to surpass the grandeur of other Italian cities. To this end the popes created increasingly extravagant churches, bridges, town squares and public spaces, including a new Saint Peter's Basilica, the Sistine Chapel, Ponte Sisto (the first bridge to be built across the Tiber since antiquity), and Piazza Navona. The Popes were also patrons of the arts engaging such artists as Michelangelo, Perugino, Raphael, Ghirlandaio, Luca Signorelli, Botticelli, and Cosimo Rosselli.

Under Pope Nicholas V, who became Pontiff on 19 March 1447, the Renaissance can be said to have begun in Rome, heralding a period in which the city became the centre of Humanism. He was the first Pope to embellish the Roman court with scholars and artists, including Lorenzo Valla and Vespasiano da Bisticci.

On 4 September 1449 Nicholas proclaimed a Jubilee for the following year, which saw a great influx of pilgrims from all Europe. The crowd was so large that in December, on Ponte Sant'Angelo, some 200 people died, crushed underfoot or drowned in the River Tiber. Later that year the Plague reappeared in the city, and Nicholas fled.

However Nicholas brought stability to the temporal power of the Papacy, a power in which the Emperor was to have no part at all. In this way, the coronation and the marriage of Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor on 16 March 1452, was more a civil ceremony. The Papacy now controlled Rome with a strong hand. A plot by Stefano Porcari, whose aim was the restoration of the Republic, was ruthlessly suppressed on January 1453. Porcari was hanged together with the other plotters, Francesco Gabadeo, Pietro de Monterotondo, Battista Sciarra and Angiolo Ronconi, but the Pope gained a treacherous reputation, as when the execution was beginning he was too drunk to confirm the grace he had previously given to Sciarra and Ronconi.

Nicholas was also actively involved in Rome's urban renewal, in collaboration with Leon Battista Alberti, including the construction of a new St Peter's Basilica.

Nicholas' successor Calixtus III neglected Nicholas's cultural policies, instead devoting himself to his greatest passion, his nephews. The Tuscan Pius II, who took the reins after his death in 1458, was a great Humanist, but did little for Rome. During his reign Lorenzo Valla demonstrated that the Donation of Constantine was a forgery. Pius was the first Pope to use guns, in campaign against the rebel barons Savelli in the neighbourhood of Rome, in 1461. One year later the bringing to Rome of the head of the Apostle St. Andrew produced a great number of pilgrims. The reign of Pope Paul II (1464–1471) was notable only for the reintroduction of the Carnival, which was to become a very popular feast in Rome in the following centuries. In the same year (1468) a plot against the Pope was uncovered, organised by the intellectuals of the Roman Academy founded by Pomponio Leto. The conspirators were sent to Castel Sant'Angelo.

More important by far was the Pontificate of Sixtus IV, considered the first Pope-King of Rome. In order to favour his relative Girolamo Riario, he promoted the unsuccessful Congiura dei Pazzi against the Medici of Florence (26 April 1478) and in Rome fought the Colonna and the Orsini. The personal politics of intrigue and war required much money, but in spite of this Sixtus was a true patron of art in the manner of Nicholas V. He reopened the Academy and reorganised the Collegio degli Abbreviatori, and in 1471 began the construction of the Vatican Library, whose first curator was Platina. The Library was officially founded on 15 June 1475. He restored several churches, including Santa Maria del Popolo, the Aqua Virgo and the Hospital of the Holy Spirit; paved several streets and also built a famous bridge over the Tiber river, which still bears his name. His main building project was the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican Palace. Its decoration called on some of the most renowned artists of the age, including Mino da Fiesole, Sandro Botticelli, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Pietro Perugino, Luca Signorelli and Pinturicchio, and in the 16th century Michelangelo decorated the ceiling with his famous masterpiece, contributing to what became one of the most famous monuments of the world. Sixtus died on 12 August 1484.

Chaos, corruption and nepotism appeared in Rome under the reign of his successors, Innocent VIII and Pope Alexander VI (1492–1503). During the vacation period between the death of the former and the election of the latter there were 220 murders in the city. Alexander had to face Charles VIII of France, who invaded Italy in 1494 and entered Rome on 31 December of that year. The Pope could only barricade himself into Castel Sant'Angelo, which had been turned into a true fortress by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger. In the end, the skilful Alexander was able to gain the support of the king, assigning his son Cesare Borgia as military counsellor for the subsequent invasion of the Kingdom of Naples. Rome was safe and, as the King directed himself southwards, the Pope again changed his position, joining the anti-French League of the Italian States which finally compelled Charles to flee to France.

The most nepotist Pope of all, Alexander, favoured his ruthless son Cesare, creating for him a personal Duchy out of territories of the Papal States, and banning from Rome Cesare's most relentless enemy, the Orsini family. In 1500 the city hosted a new Jubilee, but grew ever more unsafe as, especially at night, the streets were controlled by bands of lawless "bravi". Cesare himself assassinated Alfonso of Bisceglie; as well as, presumably, the Pope's son, Giovanni of Gandia.

The Renaissance had a great impact on Rome's appearance, with works like the Pietà by Michelangelo and the frescoes of the Borgia Apartment, all made during Innocent's reign. Rome reached the highest point of splendour under Pope Julius II (1503–1513) and his successors Leo X and Clement VII, both members of the Medici family. During this twenty-year period Rome became the greatest centre of art in the world. The old St. Peter's Basilica was demolished and a new one begun. The city hosted artists like Bramante, who built the Temple of San Pietro in Montorio and planned a great project to renovate the Vatican; Raphael, who in Rome became the most famous painter in Italy, creating frescos in the Cappella Niccolina, the Villa Farnesina, the Raphael's Rooms, and many other famous paintings. Michelangelo began the decoration of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel and executed the famous statue of Moses for the tomb of Julius. Rome lost in part its religious character, becoming increasingly a true Renaissance city, with a great number of popular feasts, horse races, parties, intrigues and licentious episodes. Its economy was prosperous, with the presence of several Tuscan bankers, including Agostino Chigi, a friend of Raphael and a patron of the arts. Despite his premature death, and to his eternal credit, Raphael also promoted for the first time the preservation of the ancient ruins.

Sack of Rome (1527)

In 1527 the ambiguous policy followed by the second Medici Pope, Pope Clement VII, resulted in the dramatic sack of the city by the unruly Imperial troops of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. After the execution of some 1,000 defenders, the pillage began.[73][74] The city was devastated for several days, many of the citizens were killed or took shelter outside the walls. Of 189 Swiss Guards on duty only 42 survived.[73][75] The Pope himself was imprisoned for months in Castel Sant'Angelo. The sack marked the end of one of the most splendid eras of modern Rome.[73][76]

The 1525's Jubilee resulted in a farce, as Martin Luther's claims had spread criticism and even hatred against the Pope's greed throughout Europe. The prestige of Rome was then challenged by the defections of the churches of Germany and England. Pope Paul III (1534–1549) tried to recover the situation by summoning the Council of Trento, although being, at the same time, the most nepotist Pope of all. He even separated Parma and Piacenza from the Papal States to create an independent duchy for his son Pier Luigi.[73] He continued the patronage of art supporting the Michelangelo's Last Judgment, asking him to renovate the Campidoglio and the ongoing construction of St. Peter's. After the shock of the sack, he also called the brilliant architect Giuliano da Sangallo the Younger to strengthen the walls of the Leonine City.[73]

The need for renovation in the religious customs became evident in the vacancy period after Paulus' death, when the streets of Rome became seat of masked carousels which satirised the Cardinals attending the conclave. His two immediate successors were feeble figures who did nothing to escape the actual Spanish suzerainty over Rome.[73]

Counter-Reformation

Pope Paul IV, elected in 1555, was a member of the anti-Spanish party in the Italian War of 1551–59, but his policy resulted in the Neapolitan troops of the viceroy again besieging Rome in 1556. Paul sued for peace, but had to accept the supremacy of Philip II of Spain.[73] He was one of the most hated Popes of all, and, after his death the raging populace burned the Holy Inquisition's palace and destroyed his marble statue on the Campidoglio.[77][78]

Pope Paul's Counter-Reformation views are well shown by his order that a central area of Rome, around the Porticus Octaviae, be delimited, creating the famous Roman Ghetto, the very constricted area in which the city's Jews were forced to live in seclusion. They had to remain in the rione Sant'Angelo and locked in at night. The Pope decreed that Jews should wear a distinctive sign, yellow hats for men[79] and veils or shawls for women. Jewish ghettos existed in Europe for the next 315 years.

The Counter-Reformation gained pace under his successors, the milder Pope Pius IV and the severe Pope Pius V. The former was a nepotist lover of court splendours, but more severe customs arrived anyway through the ideas of his advisor, the prelate Charles Borromeo, who was to become one of the most popular figures among the Rome's people. Pius V and Borromeo gave Rome a true Counter-Reformation character. All pomp was removed from the court, the jokers were expelled, and cardinals and bishops were obliged to live in the city. Blasphemy and concubinage were severely punished. Prostitutes were expelled or confined in a reserved district. The Inquisition's power in the city was reasserted, and its palace rebuilt with an increased space for prisons. During this period Michelangelo opened the Porta Pia and turned the Baths of Diocletian into the spectacular basilica of Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri, where Pius IV was buried. The expression of mannerism was meticulously widespread with Vignola, for civil and religious buildings in Rome and throughout the Papal States, his masterpieces, even before the Church of the Gesù (1568), became villas such as Villa Giulia and Villa Farnese.[80]

The pontificate of his successor, Gregory XIII, was considered a failure. As he tried to use milder measures than those of St. Pius, the worst element of the Roman population felt free to scourge again the streets. The French writer and philosopher Montaigne maintained that "life and goods were never as unsure as at the time of Gregorius XIII, perhaps", and that a confraternity even held same-sex marriage in the church of San Giovanni a Porta Latina. The courtesans repressed by Pius had now returned.

Sixtus V was of very different temper. Although short (1585–1590), his reign however remembered as one of the most effective in the modern Rome's history. He was even tougher than Pius V, and was variously nicknamed castigamatti ("punisher of the mad"), papa di ferro ("Iron Pope"), dictator and even, ironically, demon, since no other Pope before him pursued with such a determination the reform of the church and the customs. Sixtus profoundly reorganised the Papal States' administration, and cleaned the streets of Rome of thugs, procurers, dueling and so on. Even the nobles and Cardinals could not consider themselves free from the arms of Sixtus' police. The money from taxes, which were not now wasted in corruption, permitted an ambitious building program. Some ancient aqueducts were restored, and new one, the Acquedotto Felice (from Sixtus' name, Felice Peretti) was constructed. New houses were built in the desolate district of Esquilino, Viminale and Quirinale, while old houses in the centre of the city were destroyed to open new, larger streets. Sixtus's principal aim was to make Rome a better destination for pilgrimages, and the new streets were intended to permit a better access to the major Basilicas. Old obelisks were moved or erected to embellish St. John in Lateran, Santa Maria Maggiore and St. Peter, as well as Piazza del Popolo, in front of Santa Maria del Popolo.

Baroque period

In the 18th century, the Papacy reached the peak of its temporal power, the Papal States including most of Central Italy, including Latium, Umbria, Marche and the Legations of Ravenna, Ferrara and Bologna extending north into the Romagna, as well as the small enclaves of Benevento and Pontecorvo in southern Italy and the larger Comtat Venaissin around Avignon in southern France.

Baroque and Rococo architecture flourished in Rome, with several famous works being completed. Work on the Trevi Fountain began in 1732 and was completed in 1762. The Spanish Steps were designed in 1735. Pope Clement XIII's tomb by Canova was completed in 1792.

The arts also flourished throughout this period. Palazzo Nuovo became the world's first public museum in 1734 and some of the most famous views of Rome in the 18th century were etched by Giovanni Battista Piranesi. His grand vision of classic Rome inspired many to visit the city and examine the ruins themselves.

Modern history

| Rome Timeline | |

|---|---|

| Modern Rome | |

| 1798–1799 and 1800–1814 | French occupation. |

| 1848–1849 | Roman Republic with Mazzini and Garibaldi. |

| 1870 | Rome conquered by Italian troops. |

| 1874–1885 | Building of the Termini Station and founding of the Vittoriano. |

| 1922 | March on Rome. |

| 1929 | Lateran Pacts. |

| 1932–1939 | Building of Cinecittà. |

| 1943 | Bombing of Rome. |

| 1960 | Rome is site of the Summer Olympics. |

| 1975–1985 | Years of terrorism. Death of Aldo Moro. Pope John Paul II is shot. |

| 1990 | Rome is one of the locations for the 1990 FIFA World Cup |

| 2000 | Rome hosts the Jubilee. |

Italian unification

In 1870, the Pope's holdings were left in an uncertain situation when Rome itself was annexed by the Piedmont-led forces which had united the rest of Italy, after a nominal resistance by the papal forces. Between 1861 and 1929 the status of the Pope was referred to as the "Roman Question". The successive Popes were undisturbed in their palace, and certain prerogatives recognized by the Law of Guarantees, including the right to send and receive ambassadors. But the Popes did not recognise the Italian king's right to rule in Rome, and they refused to leave the Vatican compound until the dispute was resolved in 1929. Other states continued to maintain international recognition of the Holy See as a sovereign entity.

The rule of the Popes was interrupted by the short-lived Roman Republic (1798), which was under the influence of the French Revolution. During Napoleon's reign, Rome was annexed into his empire and was technically part of France. After the fall of Napoleon's Empire, the Papal States were restored by the Congress of Vienna, with the exception of Avignon and the Comtat Venaissin, which remained part of France.

Another Roman Republic arose in 1849, within the framework of revolutions of 1848. Two of the most influential figures of the Italian unification, Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi, fought for the short-lived republic. However, the actions of these two great men would not have resulted in unification without the sly leadership of Camillo Benso di Cavour, Prime Minister of Piedmont-Sardinia.

Even among those who wanted to see the peninsula unified into one country, different groups could not agree on what form a unified state would take. Vincenzo Gioberti, a Piedmontese priest, had suggested a confederation of Italian states under rulership of the Pope. His book, Of the Moral and Civil Primacy of the Italians, was published in 1843 and created a link between the Papacy and the Risorgimento. Many leading revolutionaries wanted a republic, but eventually it was a king and his chief minister who had the power to unite the Italian states as a monarchy.

In his attempt to unify Northern Italy under the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, Cavour enacted major industrialisation of the country in order to become the economic leader of Italy. In doing so, he believed that the other states would naturally come under his rule. Next, he sent the army of Piedmont to the Crimean War to join the French and British. Making minor successes in the war against Russia, cordial relations were established between Piedmont-Sardinia and France; a relationship to be exploited in the future.

The return of Pope Pius IX in Rome, with help of French troops, marked the exclusion of Rome from the unification process that was embodied in the Second Italian Independence War and the Mille expedition, after which all the Italian peninsula, except Rome and Venetia, would be unified under the House of Savoy. Garibaldi first attacked Sicily, luckily under the guise of passing British ships and landing with little resistance.

Taking the island, Garibaldi's actions were publicly denounced by Cavour but secretly encouraged via weapons supplements. This policy or real-politik, where the ends justified the means of unification, was continued as Garibaldi faced crossing the Strait of Messina. Cavour privately asked the British navy to allow Garibaldi's troops across the sea while publicly he again, denounced Garibaldi's actions. The maneuver was a success and Garibaldi's military genius carried him on to take the entire kingdom.

Cavour then moved to take Venetia and Lombardy via an alliance with France. The Italians and French together would attack the two states with France getting the city of Nice and the region of Savoy in return. However, the French pulled out of their agreement soon after, enraging Cavour who subsequently resigned. Only Lombardy had been captured at the time.

With French units still stationed at Rome however, Cavour, being called back to office, foresaw a possibility of Garibaldi attacking the Papal States and accidentally disrupting French-Italian relations. The army of Sardinia was therefore mobilised to attack the Papal States but remain outside Rome.

In the Austro-Prussian war however, a deal was made between the new Italy and Prussia, where Italy would attack Austria in return for the region of Venetia. The war was a major success for the Prussians (though the Italians did not win a single battle), and the northern front of Italy was complete.

In July 1870, the Franco-Prussian War started, and French Emperor Napoleon III could no longer protect the Papal States. Soon after, the Italian army under general Raffaele Cadorna entered Rome on 20 September, after a cannonade of three hours, through Porta Pia (see capture of Rome). The Leonine City was occupied the following day, a provisional Government Joint created by Cadorna out of local noblemen to avoid the rise of the radical factions. Rome and Latium were annexed to the Kingdom of Italy after a plebiscite held on 2 October. 133,681 voted for annexion, 1,507 opposed (in Rome itself, there were 40,785 "Yes" and 57 "No").

When Rome was eventually taken, the Italian government reportedly intended to let Pope Pius IX keep the part of Rome, west of the Tiber, known as the Leonine City as a small remaining Papal State, but Pius IX rejected the offer because acceptance would have been an implied endorsement of the legitimacy of the Italian kingdom's rule over his former domain.[81] One week after entering Rome, the Italian troops had taken the entire city save for the Apostolic Palace; the inhabitants of the city then voted to join Italy.[82] On 1 July 1871, Rome became the official capital of united Italy and from then until June 1929 the popes had no temporal power.

The pope referred to himself during this time as the "prisoner of the Vatican", although he was not actually restrained from coming and going. Pius IX took steps to ensure self-sufficiency, such as the construction of the Vatican Pharmacy. Italian nobility who owed their titles to the pope rather than the royal family became known as the Black Nobility during this period because of their purported mourning.

Kingdom of Italy