Voltage-gated potassium channel

Voltage-gated potassium channels (VGKCs) are transmembrane channels specific for potassium and sensitive to voltage changes in the cell's membrane potential. During action potentials, they play a crucial role in returning the depolarized cell to a resting state.

| Eukaryotic potassium channel | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

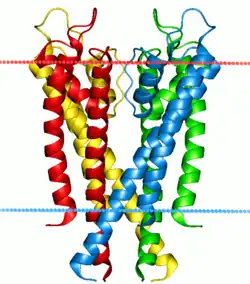

Potassium channel, structure in a membrane-like environment. Calculated hydrocarbon boundaries of the lipid bilayer are indicated by red and blue dots. | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Ion_trans | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00520 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR005821 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1bl8 / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| TCDB | 1.A.1 | ||||||||

| OPM superfamily | 8 | ||||||||

| OPM protein | 2a79 | ||||||||

| Membranome | 217 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Ion channel (bacterial) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Potassium channel KcsA. Calculated hydrocarbon boundaries of the lipid bilayer are indicated by red and blue dots. | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Ion_trans_2 | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF07885 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR013099 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1bl8 / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| OPM protein | 1r3j | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Slow voltage-gated potassium channel (Potassium channel, voltage-dependent, beta subunit, KCNE) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | ISK_Channel | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF02060 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR000369 | ||||||||

| TCDB | 8.A.10 | ||||||||

| Membranome | 218 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| KCNQ voltage-gated potassium channel | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | KCNQ_channel | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF03520 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR013821 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Kv2 voltage-gated K+ channel | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Kv2channel | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF03521 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR003973 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Classification

Alpha subunits

Alpha subunits form the actual conductance pore. Based on sequence homology of the hydrophobic transmembrane cores, the alpha subunits of voltage-gated potassium channels are grouped into 12 classes. These are labeled Kvα1-12.[1] The following is a list of the 40 known human voltage-gated potassium channel alpha subunits grouped first according to function and then subgrouped according to the Kv sequence homology classification scheme:

Delayed rectifier

slowly inactivating or non-inactivating

- Kvα1.x - Shaker-related: Kv1.1 (KCNA1), Kv1.2 (KCNA2), Kv1.3 (KCNA3), Kv1.5 (KCNA5), Kv1.6 (KCNA6), Kv1.7 (KCNA7), Kv1.8 (KCNA10)

- Kvα2.x - Shab-related: Kv2.1 (KCNB1), Kv2.2 (KCNB2)

- Kvα3.x - Shaw-related: Kv3.1 (KCNC1), Kv3.2 (KCNC2)

- Kvα7.x: Kv7.1 (KCNQ1) - KvLQT1, Kv7.2 (KCNQ2), Kv7.3 (KCNQ3), Kv7.4 (KCNQ4), Kv7.5 (KCNQ5)

- Kvα10.x: Kv10.1 (KCNH1)

A-type potassium channel

rapidly inactivating

Outward-rectifying

- Kvα10.x: Kv10.2 (KCNH5)

Inwardly-rectifying

Passes current more easily in the inward direction (into the cell, from outside).

- Kvα11.x - ether-a-go-go potassium channels: Kv11.1 (KCNH2) - hERG, Kv11.2 (KCNH6), Kv11.3 (KCNH7)

Modifier/silencer

Unable to form functional channels as homotetramers but instead heterotetramerize with Kvα2 family members to form conductive channels.

Beta subunits

Beta subunits are auxiliary proteins that associate with alpha subunits, sometimes in a α4β4 stoichiometry.[2] These subunits do not conduct current on their own but rather modulate the activity of Kv channels.[3]

- Kvβ1 (KCNAB1)

- Kvβ2 (KCNAB2)

- Kvβ3 (KCNAB3)

- minK[4] (KCNE1)

- MiRP1[5] (KCNE2)

- MiRP2 (KCNE3)

- MiRP3 (KCNE4)

- KCNE1-like (KCNE1L)

- KCNIP1 (KCNIP1)

- KCNIP2 (KCNIP2)

- KCNIP3 (KCNIP3)

- KCNIP4 (KCNIP4)

Proteins minK and MiRP1 are putative hERG beta subunits.[6]

Animal research

The voltage-gated K+ channels that provide the outward currents of action potentials have similarities to bacterial K+ channels.

These channels have been studied by X-ray diffraction, allowing determination of structural features at atomic resolution.

The function of these channels is explored by electrophysiological studies.

Genetic approaches include screening for behavioral changes in animals with mutations in K+ channel genes. Such genetic methods allowed the genetic identification of the "Shaker" K+ channel gene in Drosophila before ion channel gene sequences were well known.

Study of the altered properties of voltage-gated K+ channel proteins produced by mutated genes has helped reveal the functional roles of K+ channel protein domains and even individual amino acids within their structures.

Structure

Typically, vertebrate voltage-gated K+ channels are tetramers of four identical subunits arranged as a ring, each contributing to the wall of the trans-membrane K+ pore. Each subunit is composed of six membrane spanning hydrophobic α-helical sequences, as well as a voltage sensor in S4. The intracellular side of the membrane contains both amino and carboxy termini.[7] The high resolution crystallographic structure of the rat Kvα1.2/β2 channel has recently been solved (Protein Databank Accession Number 2A79),[8] and then refined in a lipid membrane-like environment (PDB: 2r9r).

Selectivity

Voltage-gated K+ channels are selective for K+ over other cations such as Na+. There is a selectivity filter at the narrowest part of the transmembrane pore.

Channel mutation studies have revealed the parts of the subunits that are essential for ion selectivity. They include the amino acid sequence (Thr-Val-Gly-Tyr-Gly) or (Thr-Val-Gly-Phe-Gly) typical to the selectivity filter of voltage-gated K+ channels. As K+ passes through the pore, interactions between potassium ions and water molecules are prevented and the K+ interacts with specific atomic components of the Thr-Val-Gly-[YF]-Gly sequences from the four channel subunits .

It may seem counterintuitive that a channel should allow potassium ions but not the smaller sodium ions through. However in an aqueous environment, potassium and sodium cations are solvated by water molecules. When moving through the selectivity filter of the potassium channel, the water-K+ interactions are replaced by interactions between K+ and carbonyl groups of the channel protein. The diameter of the selectivity filter is ideal for the potassium cation, but too big for the smaller sodium cation. Hence the potassium cations are well "solvated" by the protein carbonyl groups, but these same carbonyl groups are too far apart to adequately solvate the sodium cation. Hence, the passage of potassium cations through this selectivity filter is strongly favored over sodium cations.

Open and closed conformations

The structure of the mammalian voltage-gated K+ channel has been used to explain its ability to respond to the voltage across the membrane. Upon opening of the channel, conformational changes in the voltage-sensor domains (VSD) result in the transfer of 12-13 elementary charges across the membrane electric field. This charge transfer is measured as a transient capacitive current that precedes opening of the channel. Several charged residues of the VSD, in particular four arginine residues located regularly at every third position on the S4 segment, are known to move across the transmembrane field and contribute to the gating charge. The position of these arginines, known as gating arginines, are highly conserved in all voltage-gated potassium, sodium, or calcium channels. However, the extent of their movement and their displacement across the transmembrane potential has been subject to extensive debate.[9] Specific domains of the channel subunits have been identified that are responsible for voltage-sensing and converting between the open and closed conformations of the channel. There are at least two closed conformations. In the first, the channel can open if the membrane potential becomes more positive. This type of gating is mediated by a voltage-sensing domain that consists of the S4 alpha helix that contains 6–7 positive charges. Changes in membrane potential cause this alpha helix to move in the lipid bilayer. This movement in turn results in a conformational change in the adjacent S5–S6 helices that form the channel pore and cause this pore to open or close. In the second, "N-type" inactivation, voltage-gated K+ channels inactivate after opening, entering a distinctive, closed conformation. In this inactivated conformation, the channel cannot open, even if the transmembrane voltage is favorable. The amino terminal domain of the K+ channel or an auxiliary protein can mediate "N-type" inactivation. The mechanism of this type of inactivation has been described as a "ball and chain" model, where the N-terminus of the protein forms a ball that is tethered to the rest of the protein through a loop (the chain).[10] The tethered ball blocks the inner porehole, preventing ion movement through the channel.[11][12]

Pharmacology

For blockers and activators of voltage gated potassium channels see: potassium channel blocker and potassium channel opener.

See also

References

- Gutman GA, Chandy KG, Grissmer S, Lazdunski M, McKinnon D, Pardo LA, Robertson GA, Rudy B, Sanguinetti MC, Stühmer W, Wang X (December 2005). "International Union of Pharmacology. LIII. Nomenclature and molecular relationships of voltage-gated potassium channels". Pharmacological Reviews. 57 (4): 473–508. doi:10.1124/pr.57.4.10. PMID 16382104. S2CID 219195192.

- Pongs O, Leicher T, Berger M, Roeper J, Bähring R, Wray D, Giese KP, Silva AJ, Storm JF (April 1999). "Functional and molecular aspects of voltage-gated K+ channel beta subunits". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 868 (Apr 30): 344–55. Bibcode:1999NYASA.868..344P. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11296.x. PMID 10414304. S2CID 21621084.

- Li Y, Um SY, McDonald TV (June 2006). "Voltage-gated potassium channels: regulation by accessory subunits". The Neuroscientist. 12 (3): 199–210. doi:10.1177/1073858406287717. PMID 16684966. S2CID 24418687.

- Zhang M, Jiang M, Tseng GN (May 2001). "minK-related peptide 1 associates with Kv4.2 and modulates its gating function: potential role as beta subunit of cardiac transient outward channel?". Circulation Research. 88 (10): 1012–9. doi:10.1161/hh1001.090839. PMID 11375270.

- McCrossan ZA, Abbott GW (November 2004). "The MinK-related peptides". Neuropharmacology. 47 (6): 787–821. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.06.018. PMID 15527815. S2CID 41340789.

- Anantharam A, Abbott GW (2005). Does hERG coassemble with a beta subunit? Evidence for roles of MinK and MiRP1. pp. 100–12, discussion 112–7, 155–8. doi:10.1002/047002142X.fmatter. ISBN 9780470021408. PMID 16050264.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Yellen G (September 2002). "The voltage-gated potassium channels and their relatives". Nature. 419 (6902): 35–42. doi:10.1038/nature00978. PMID 12214225. S2CID 4420877.

- Long SB, Campbell EB, Mackinnon R (August 2005). "Crystal structure of a mammalian voltage-dependent Shaker family K+ channel". Science. 309 (5736): 897–903. Bibcode:2005Sci...309..897L. doi:10.1126/science.1116269. PMID 16002581. S2CID 6072007.

- Lee SY, Lee A, Chen J, MacKinnon R (October 2005). "Structure of the KvAP voltage-dependent K+ channel and its dependence on the lipid membrane". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (43): 15441–6. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10215441L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0507651102. PMC 1253646. PMID 16223877.

- Antz C, Fakler B (August 1998). "Fast Inactivation of Voltage-Gated K(+) Channels: From Cartoon to Structure" (PDF). News in Physiological Sciences. 13 (4): 177–182. doi:10.1152/physiologyonline.1998.13.4.177. PMID 11390785.

- Armstrong CM, Bezanilla F (April 1973). "Currents related to movement of the gating particles of the sodium channels". Nature. 242 (5398): 459–61. Bibcode:1973Natur.242..459A. doi:10.1038/242459a0. PMID 4700900. S2CID 4261606.

- Murrell-Lagnado RD, Aldrich RW (December 1993). "Energetics of Shaker K channels block by inactivation peptides". The Journal of General Physiology. 102 (6): 977–1003. doi:10.1085/jgp.102.6.977. PMC 2229186. PMID 8133246.

External links

- Voltage-Gated+Potassium+Channels at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- "Voltage-Gated Potassium Channels". IUPHAR Database of Receptors and Ion Channels. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology.

- Li B, Gallin WJ (January 2004). "VKCDB: voltage-gated potassium channel database". BMC Bioinformatics. 5: 3. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-5-3. PMC 317694. PMID 14715090.

- "Voltage-gated potassium channel database (VKCDB)" at ualberta.ca

- UMich Orientation of Proteins in Membranes families/superfamily-8 - Spatial positions of voltage gated potassium channels in membranes