Hyperemesis gravidarum

Hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) is a pregnancy complication that is characterized by severe nausea, vomiting, weight loss, and possibly dehydration.[1] Feeling faint may also occur.[2] It is considered more severe than morning sickness.[2] Symptoms often get better after the 20th week of pregnancy but may last the entire pregnancy duration.[7][8][9][10][2]

| Hyperemesis gravidarum | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Obstetrics Gastroenterology |

| Symptoms | Nausea and vomiting such that weight loss and dehydration occur[1] |

| Duration | Often gets better but may last entire pregnancy[2] |

| Causes | Unknown[3] |

| Risk factors | First pregnancy, multiple pregnancy, obesity, prior or family history of hyperemesis gravidarum, trophoblastic disorder, history of an eating disorder[3][4] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Urinary tract infection, high thyroid levels[5] |

| Treatment | Drinking fluids, bland diet, intravenous fluids[2] |

| Medication | Pyridoxine, metoclopramide[5] |

| Frequency | ~1% of pregnant women[6] |

The exact causes of hyperemesis gravidarum are unknown.[3] Risk factors include the first pregnancy, multiple pregnancy, obesity, prior or family history of HG, trophoblastic disorder, and a history of eating disorders.[3][4] Diagnosis is usually made based on the observed signs and symptoms.[3] HG has been technically defined as more than three episodes of vomiting per day such that weight loss of 5% or three kilograms has occurred and ketones are present in the urine.[3] Other potential causes of the symptoms should be excluded, including urinary tract infection and an overactive thyroid.[5]

Treatment includes drinking fluids and a bland diet.[2] Recommendations may include electrolyte-replacement drinks, thiamine, and a higher protein diet.[3][11] Some people require intravenous fluids.[2] With respect to medications, pyridoxine or metoclopramide are preferred.[5] Prochlorperazine, dimenhydrinate, ondansetron (sold under the brand-name Zofran) or corticosteroids may be used if these are not effective.[3][5] Hospitalization may be required due to the severe symptoms associated.[10][3] Psychotherapy may improve outcomes.[3] Evidence for acupressure is poor.[3]

While vomiting in pregnancy has been described as early as 2,000 BC, the first clear medical description of HG was in 1852 by Paul Antoine Dubois.[12] HG is estimated to affect 0.3–2.0% of pregnant women, although some sources say the figure can be as high as 3%.[7][10][6] While previously known as a common cause of death in pregnancy, with proper treatment this is now very rare.[13][14] Those affected have a lower risk of miscarriage but a higher risk of premature birth.[4] Some pregnant women choose to have an abortion due to HG symptoms.[11]

Signs and symptoms

When vomiting is severe, it may result in the following:[15]

- Loss of 5% or more of pre-pregnancy body weight

- Dehydration, causing ketosis,[16] and constipation

- Nutritional disorders, such as vitamin B1 (thiamine) deficiency, vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) deficiency or vitamin B12 (cobalamin) deficiency

- Metabolic imbalances such as metabolic ketoacidosis[15] or thyrotoxicosis[17]

- Physical and emotional stress

- Difficulty with activities of daily living

Symptoms can be aggravated by hunger, fatigue, prenatal vitamins (especially those containing iron), and diet.[18] Many women with HG are extremely sensitive to odors in their environment; certain smells may exacerbate symptoms. Excessive salivation, also known as sialorrhea gravidarum, is another symptom experienced by some women.

Hyperemesis gravidarum tends to occur in the first trimester of pregnancy[16] and lasts significantly longer than morning sickness. While most women will experience near-complete relief of morning sickness symptoms near the beginning of their second trimester, some people with HG will experience severe symptoms until they give birth to their baby, and sometimes even after giving birth.[19]

A small percentage rarely vomit, but the nausea still causes most (if not all) of the same issues that hyperemesis with vomiting does.[20]

Causes

There are numerous theories regarding the cause of HG, but the cause remains controversial. It is thought that HG is due to a combination of factors which may vary between women and include genetics.[15] Women with family members who had HG are more likely to develop the disease.[21]

One factor is an adverse reaction to the hormonal changes of pregnancy, in particular, elevated levels of beta human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG).[22][23] This theory would also explain why hyperemesis gravidarum is most frequently encountered in the first trimester (often around 8–12 weeks of gestation), as β-hCG levels are highest at that time and decline afterward. Another postulated cause of HG is an increase in maternal levels of estrogens (decreasing intestinal motility and gastric emptying leading to nausea/vomiting).[15]

More recently, another cause of HG was discovered: "Evidence suggests abnormal levels of the hormone GDF15 are associated with HG. The validation of a second risk variant, rs1054221, provides further support for GDF15's role in the etiology of HG. Additionally, maternal genes appear to play a more significant role than paternal DNA in contributing to the severity of NVP."[24]

Pathophysiology

Although the pathophysiology of HG is poorly understood, the most commonly accepted theory suggests that levels of β-hCG are associated with it.[5] Leptin, a hormone that inhibits hunger, may also play a role.[25]

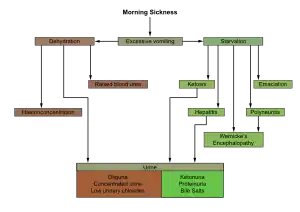

Possible pathophysiological processes involved are summarized in the following table:[26]

| Source | Cause | Pathophysiology |

|---|---|---|

| Placenta | β-hCG |

|

|

| |

| Gastrointestinal tract | Helicobacter pylori | Increased steroid levels in circulation[28] |

Diagnosis

Hyperemesis gravidarum is considered a diagnosis of exclusion.[15] HG can be associated with serious problems in the mother or baby, such as Wernicke's encephalopathy, coagulopathy and peripheral neuropathy.[5]

Women experiencing hyperemesis gravidarum often are dehydrated and lose weight despite efforts to eat.[29][30] The onset of the nausea and vomiting in hyperemesis gravidarum is typically before the 20th week of pregnancy.[15]

Differential diagnosis

Diagnoses to be ruled out include the following:[26]

| Type | Differential diagnoses |

|---|---|

| Infections

(usually accompanied by fever or associated neurological symptoms) |

|

| Gastrointestinal disorders

(usually accompanied by abdominal pain) |

|

| Metabolic |

|

| Drugs |

|

| Gestational trophoblastic diseases (rule out with urine β-hCG) | |

Investigations

Common investigations include blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and electrolytes, liver function tests, urinalysis,[30] and thyroid function tests. Hematological investigations include hematocrit levels, which are usually raised in HG.[30] An ultrasound scan may be needed to know gestational status and to exclude molar or partial molar pregnancy.[31]

Management

Dry bland food and oral rehydration are first-line treatments.[32] Due to the potential for severe dehydration and other complications, HG is treated as an emergency. If conservative dietary measures fail, more extensive treatment such as the use of antiemetic medications and intravenous rehydration may be required. If oral nutrition is insufficient, intravenous nutritional support may be needed.[16] For women who require hospital admission, thromboembolic stockings or low-molecular-weight heparin may be used as measures to prevent the formation of a blood clot.[26]

Intravenous fluids

Intravenous (IV) hydration often includes supplementation of electrolytes as persistent vomiting frequently leads to a deficiency. Likewise, supplementation for lost thiamine (Vitamin B1) must be considered to reduce the risk of Wernicke's encephalopathy.[33] A and B vitamins are depleted within two weeks, so extended malnutrition indicates a need for evaluation and supplementation. In addition, electrolyte levels should be monitored and supplemented; of particular concern are sodium and potassium.

After IV rehydration is completed, patients typically begin to tolerate frequent small liquid or bland meals. After rehydration, treatment focuses on managing symptoms to allow normal intake of food. However, cycles of hydration and dehydration can occur, making continuing care necessary. Home care is available in the form of a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line for hydration and nutrition.[34] Home treatment is often less expensive and reduces the risk for a hospital-acquired infection compared with long-term or repeated hospitalizations.

Medications

A number of antiemetics are effective and safe in pregnancy including: pyridoxine/doxylamine, antihistamines (such as diphenhydramine), and phenothiazines (such as promethazine).[35] With respect to effectiveness, it is unknown if one is superior to another for relieving nausea or vomiting.[35] Limited evidence from published clinical trials suggests the use of medications to treat hyperemesis gravidarum.[36]

While pyridoxine/doxylamine, a combination of vitamin B6 and doxylamine, is effective in nausea and vomiting of pregnancy,[37] some have questioned its effectiveness in HG.[38]

Ondansetron may be beneficial, however, there are some concerns regarding an association with cleft palate,[39] and there is little high-quality data.[35] Metoclopramide is also used and relatively well tolerated.[37] Evidence for the use of corticosteroids is weak; there is some evidence that corticosteroid use in pregnant women may slightly increase the risk of cleft lip and cleft palate in the infant and may suppress fetal adrenal activity.[15][40] However, hydrocortisone and prednisolone are inactivated in the placenta and may be used in the treatment of hyperemesis gravidarum after 12 weeks.[15]

Medicinal cannabis has been used to treat pregnancy-associated hyperemesis.[41]

Nutritional support

Women not responding to IV rehydration and medication may require nutritional support. Patients might receive parenteral nutrition (intravenous feeding via a PICC line) or enteral nutrition (via a nasogastric tube or a nasojejunal tube). There is only limited evidence from trials to support the use of vitamin B6 to improve outcome.[36] An oversupply of nutrition (hyperalimentation) may be necessary in certain cases to help maintain volume requirements and allow weight gain.[31] A physician might also prescribe Vitamin B1 (to prevent Wernicke's encephalopathy) and folic acid.[26]

Alternative medicine

Acupuncture (both with P6 and traditional method) has been found to be ineffective.[36] The use of ginger products may be helpful, but evidence of effectiveness is limited and inconsistent, though three recent studies support ginger over placebo.[36]

Complications

Pregnant woman

If HG is inadequately treated, anemia,[15] hyponatremia,[15] Wernicke's encephalopathy,[15] kidney failure, central pontine myelinolysis, coagulopathy, atrophy, Mallory-Weiss tears,[15] hypoglycemia, jaundice, malnutrition, pneumomediastinum, rhabdomyolysis, deconditioning, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, splenic avulsion, or vasospasms of cerebral arteries are possible consequences. Depression and post-traumatic stress disorder[42] are common secondary complications of HG and emotional support can be beneficial.[15]

Infant

The effects of HG on the fetus are mainly due to electrolyte imbalances caused by HG in the mother.[26] Infants of women with severe hyperemesis who gain less than 7 kilograms (15 lb) during pregnancy tend to be of lower birth weight, small for gestational age, and born before 37 weeks gestation.[16] In contrast, infants of women with hyperemesis who have a pregnancy weight gain of more than 7 kilograms appear similar to infants from uncomplicated pregnancies.[43] There is no significant difference in the neonatal death rate in infants born to mothers with HG compared to infants born to mothers who do not have HG.[15] Children born to mothers with undertreated HG have a fourfold increase in neurobehavioral diagnoses.[44]

Epidemiology

Vomiting is a common condition affecting about 50% of pregnant women, with another 25% having nausea.[45] However, the incidence of HG is only 0.3–1.5%.[5] After preterm labor, hyperemesis gravidarum is the second most common reason for hospital admission during the first half of pregnancy.[15] Factors such as infection with Helicobacter pylori, a rise in thyroid hormone production, low age, low body mass index prior to pregnancy, multiple pregnancies, molar pregnancies, and a history of hyperemesis gravidarum have been associated with the development of HG.[15]

History

Thalidomide was prescribed for treatment of HG in Europe until it was recognized that thalidomide is teratogenic and is a cause of phocomelia in neonates.[46]

Etymology

Hyperemesis gravidarum is from the Greek hyper-, meaning excessive, and emesis, meaning vomiting, and the Latin gravidarum, the feminine genitive plural form of an adjective, here used as a noun, meaning "pregnant [woman]". Therefore, hyperemesis gravidarum means "excessive vomiting of pregnant women".

Notable cases

Author Charlotte Brontë is often thought to have had hyperemesis gravidarum. She died in 1855 while four months pregnant, having been affected by intractable nausea and vomiting throughout her pregnancy, and was unable to tolerate food or even water.[47]

Catherine, Princess of Wales was hospitalised due to hyperemesis gravidarum during her first pregnancy, and was treated for a similar condition during the subsequent two.[48][49]

Comedienne Amy Schumer cancelled the remainder of a tour due to hyperemesis gravidarum.[50]

References

- "Management of hyperemesis gravidarum". Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin. 51 (11): 126–129. November 2013. doi:10.1136/dtb.2013.11.0215. PMID 24227770. S2CID 20885167.

- "Pregnancy". Office on Women's Health. September 27, 2010. Archived from the original on 10 December 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- Jueckstock JK, Kaestner R, Mylonas I (July 2010). "Managing hyperemesis gravidarum: a multimodal challenge". BMC Medicine. 8: 46. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-8-46. PMC 2913953. PMID 20633258.

- Ferri FF (2012). Ferri's clinical advisor 2013 5 books in 1 (1st ed.). Elsevier Mosby. p. 538. ISBN 9780323083737.

- Sheehan P (September 2007). "Hyperemesis gravidarum--assessment and management" (PDF). Australian Family Physician. 36 (9): 698–701. PMID 17885701. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-06-06.

- Goodwin TM (September 2008). "Hyperemesis gravidarum". Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 35 (3): 401–17, viii. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2008.04.002. PMID 18760227.

- Zimmerman CF, Ilstad-Minnihan AB, Bruggeman BS, Bruggeman BJ, Dayton KJ, Joseph N, et al. (2022-01-02). "Thyroid Storm Caused by Hyperemesis Gravidarum". AACE Clinical Case Reports. 8 (3): 124–127. doi:10.1016/j.aace.2021.12.005. PMC 9123575. PMID 35602873.

- Tan JY, Loh KC, Yeo GS, Chee YC (June 2002). "Transient hyperthyroidism of hyperemesis gravidarum". BJOG. 109 (6): 683–688. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01223.x. PMID 12118648. S2CID 34693980.

- Goodwin TM, Montoro M, Mestman JH (September 1992). "Transient hyperthyroidism and hyperemesis gravidarum: clinical aspects". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 167 (3): 648–652. doi:10.1016/s0002-9378(11)91565-8. PMID 1382389.

- McParlin C, O'Donnell A, Robson SC, Beyer F, Moloney E, Bryant A, et al. (October 2016). "Treatments for Hyperemesis Gravidarum and Nausea and Vomiting in Pregnancy: A Systematic Review". JAMA. 316 (13): 1392–1401. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.14337. PMID 27701665. S2CID 205074563.

- Gabbe SG (2012). Obstetrics : normal and problem pregnancies (6th ed.). Elsevier/Saunders. p. 117. ISBN 9781437719352.

- Davis CJ (1986). Nausea and Vomiting : Mechanisms and Treatment. Springer. p. 152. ISBN 9783642704796.

- Kumar G (2011). Early Pregnancy Issues for the MRCOG and Beyond. Cambridge University Press. p. Chapter 6. ISBN 9781107717992.

- DeLegge MH (2007). Handbook of home nutrition support. Sudbury, Mass.: Jones and Bartlett. p. 320. ISBN 9780763747695.

- Summers A (July 2012). "Emergency management of hyperemesis gravidarum". Emergency Nurse. 20 (4): 24–28. doi:10.7748/en2012.07.20.4.24.c9206. PMID 22876404.

- Ahmed KT, Almashhrawi AA, Rahman RN, Hammoud GM, Ibdah JA (November 2013). "Liver diseases in pregnancy: diseases unique to pregnancy". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 19 (43): 7639–7646. doi:10.3748/wjg.v19.i43.7639. PMC 3837262. PMID 24282353.

- Matthews DC, Syed AA (June 2011). "The role of TSH receptor antibodies in the management of Graves' disease". European Journal of Internal Medicine. 22 (3): 213–216. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2011.02.006. PMID 21570635.

- Carlson KJ, Eisenstat SJ, Ziporyn T (2004). The New Harvard Guide to Women's Health. Harvard University Press. pp. 392–3. ISBN 978-0-674-01343-8.

- "Do I Have Morning Sickness or HG?". H.E.R. Foundation. Archived from the original on 30 November 2012. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- "Hyperemesis gravidarum: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2021-02-25.

- Zhang Y, Cantor RM, MacGibbon K, Romero R, Goodwin TM, Mullin PM, Fejzo MS (March 2011). "Familial aggregation of hyperemesis gravidarum". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 204 (3): 230.e1–230.e7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2010.09.018. PMC 3030697. PMID 20974461.

- Cole LA (August 2010). "Biological functions of hCG and hCG-related molecules". Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 8 (102): 102. doi:10.1186/1477-7827-8-102. PMC 2936313. PMID 20735820.

- Hershman JM (June 2004). "Physiological and pathological aspects of the effect of human chorionic gonadotropin on the thyroid". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 18 (2): 249–265. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2004.03.010. PMID 15157839.

- Mullin P, MacGibbon K, Morgan Z, Fejzo M (1 January 2020). "82: Additional risk variant in GDF15 and a stronger maternal genetic influence linked to Hyperemesis Gravidarum". American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 222 (1): S68. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.11.098. ISSN 0002-9378.

- Aka N, Atalay S, Sayharman S, Kiliç D, Köse G, Küçüközkan T (August 2006). "Leptin and leptin receptor levels in pregnant women with hyperemesis gravidarum". The Australian & New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 46 (4): 274–277. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.2006.00590.x. PMID 16866785. S2CID 72562308.

- Bourne TH, Condous G, eds. (2006). Handbook of early pregnancy care. Informa Healthcare. pp. 149–154. ISBN 9781842143230.

- Verberg MF, Gillott DJ, Al-Fardan N, Grudzinskas JG (September–October 2005). "Hyperemesis gravidarum, a literature review". Human Reproduction Update. 11 (5): 527–539. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmi021. PMID 16006438.

- Bagis T, Gumurdulu Y, Kayaselcuk F, Yilmaz ES, Killicadag E, Tarim E (November 2002). "Endoscopy in hyperemesis gravidarum and Helicobacter pylori infection". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 79 (2): 105–109. doi:10.1016/s0020-7292(02)00230-8. PMID 12427393. S2CID 36603396.

- "Hyperemesis Gravidarum (Severe Nausea and Vomiting During Pregnancy)". Cleveland Clinic. 2012. Archived from the original on 15 December 2012. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- Medline Plus (2012). "Hyperemesis gravidarum". National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Evans AT, ed. (2007). Manual of obstetrics (7th ed.). Wolters Kluwer / Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 265–8. ISBN 9780781796965. Archived from the original on 2017-09-11.

- Office on Women's Health (2010). "Pregnancy Complications". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- British National Formulary (March 2003). "4.6 Drugs used in nausea and vertigo – Vomiting of pregnancy". BNF (45 ed.).

- Tuot D, Gibson S, Caughey AB, Frassetto LA (March 2010). "Intradialytic hyperalimentation as adjuvant support in pregnant hemodialysis patients: case report and review of the literature". International Urology and Nephrology. 42 (1): 233–237. doi:10.1007/s11255-009-9671-5. PMC 2844957. PMID 19911296.

- Jarvis S, Nelson-Piercy C (June 2011). "Management of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy". BMJ. 342: d3606. doi:10.1136/bmj.d3606. PMID 21685438. S2CID 32242306.

- Matthews A, Haas DM, O'Mathúna DP, Dowswell T (September 2015). "Interventions for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (9): CD007575. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007575.pub4. PMC 4004939. PMID 26348534.

- Tan PC, Omar SZ (April 2011). "Contemporary approaches to hyperemesis during pregnancy". Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 23 (2): 87–93. doi:10.1097/GCO.0b013e328342d208. PMID 21297474. S2CID 11743580.

- Tamay AG, Kuşçu NK (November 2011). "Hyperemesis gravidarum: current aspect". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 31 (8): 708–712. doi:10.3109/01443615.2011.611918. PMID 22085059. S2CID 20818005.

- Koren G (October 2012). "Motherisk update. Is ondansetron safe for use during pregnancy?". Canadian Family Physician. 58 (10): 1092–1093. PMC 3470505. PMID 23064917.

- Poon SL (October 2011). "Towards evidence-based emergency medicine: Best BETs from the Manchester Royal Infirmary. BET 2: Steroid therapy in the treatment of intractable hyperemesis gravidarum". Emergency Medicine Journal. 28 (10): 898–900. doi:10.1136/emermed-2011-200636. PMID 21918097. S2CID 6667779.

- Jaques SC, Kingsbury A, Henshcke P, Chomchai C, Clews S, Falconer J, et al. (June 2014). "Cannabis, the pregnant woman and her child: weeding out the myths". Journal of Perinatology. 34 (6): 417–424. doi:10.1038/jp.2013.180. PMID 24457255. S2CID 28771505.

- Christodoulou-Smith J, Gold JI, Romero R, Goodwin TM, Macgibbon KW, Mullin PM, Fejzo MS (November 2011). "Posttraumatic stress symptoms following pregnancy complicated by hyperemesis gravidarum". The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 24 (11): 1307–1311. doi:10.3109/14767058.2011.582904. PMC 3514078. PMID 21635201.

- Dodds L, Fell DB, Joseph KS, Allen VM, Butler B (February 2006). "Outcomes of pregnancies complicated by hyperemesis gravidarum". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 107 (2 Pt 1): 285–292. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000195060.22832.cd. PMID 16449113. S2CID 29255084.

- Fejzo MS, Magtira A, Schoenberg FP, Macgibbon K, Mullin PM (June 2015). "Neurodevelopmental delay in children exposed in utero to hyperemesis gravidarum" (PDF). European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 189: 79–84. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.03.028. PMID 25898368. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04.

- Niebyl JR (October 2010). "Clinical practice. Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy". The New England Journal of Medicine. 363 (16): 1544–1550. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1003896. PMID 20942670. S2CID 205068587.

- Cohen WR, ed. (2000). Cherry and Merkatz's complications of pregnancy (5th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 124. ISBN 9780683016734.

- McSweeny L (2010-06-03). "What is acute morning sickness?". The Age. Archived from the original on 2012-12-06. Retrieved 2012-12-04.

- "Prince William, Kate expecting 2nd child". 8 September 2014. Archived from the original on 8 September 2014. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- Kensington Palace (2017-09-04). "Read the press release in full ↓pic.twitter.com/vDTgGD2aGF". @KensingtonRoyal. Archived from the original on 2017-09-04. Retrieved 2017-09-04.

- Southern K (23 Feb 2019). "Amy Schumer cancels US tour due to complications from hyperemesis in third trimester of pregnancy". Retrieved 24 Feb 2019.