Vitamin C megadosage

Vitamin C megadosage is a term describing the consumption or injection of vitamin C (ascorbic acid) in doses well beyond the current United States Recommended Dietary Allowance of 90 milligrams per day, and often well beyond the tolerable upper intake level of 2,000 milligrams per day.[1] There is no scientific evidence that vitamin C megadosage helps to cure or prevent cancer, the common cold, or some other medical conditions.[2][3]

| This article is part of a series on |

| Alternative medicine |

|---|

|

Historical advocates of vitamin C megadosage include Linus Pauling, who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1954. Pauling argued that because humans lack a functional form of L-gulonolactone oxidase, an enzyme required to make vitamin C that is functional in most other mammals, plants, insects, and other life forms, humans have developed a number of adaptations to cope with the relative deficiency. These adaptations, he argued, ultimately shortened lifespan but could be reversed or mitigated by supplementing humans with the hypothetical amount of vitamin C that would have been produced in the body if the enzyme were working.

Vitamin C megadoses are claimed by alternative medicine advocates including Matthias Rath and Patrick Holford to have preventive and curative effects on diseases such as cancer and AIDS,[4][5] but the available scientific evidence does not support these claims.[3] Some trials show some effect in combination with other therapies, but this does not imply vitamin C megadoses in themselves have any therapeutic effect.[6]

Background

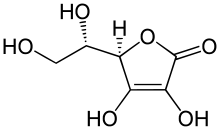

Vitamin C is an essential nutrient used in the production of collagen and other biomolecules, and for the prevention of scurvy.[7] It is also an antioxidant, which has led to its endorsement by some researchers as a complementary therapy for improving quality of life.[8] Certain animal species, including the haplorhine primates (which include humans),[9][10] members of the Caviidae family of rodents (including guinea pigs and capybaras),[11] most species of bats,[12] many passerine birds,[13] and about 96% of fish (the teleosts),[13] cannot synthesize vitamin C internally and must therefore rely on external sources, typically obtained from food.

For humans, the World Health Organization recommends a daily intake of 45 mg/day of vitamin C for healthy adults, and 25–30 mg/day in infants.[14]

Since its discovery, vitamin C has been considered almost a panacea by some,[15] although this led to suspicions of it being overhyped by others.[16] Vitamin C has long been promoted in alternative medicine as a treatment for the common cold, cancer, polio, and various other illnesses. The evidence for these claims is mixed. Since the 1930s, when it first became available in pure form, some physicians have experimented with higher-than-recommended vitamin C consumption or injection.[17] Orthomolecular-based megadose recommendations for vitamin C are based mainly on theoretical speculation and observational studies, such as those published by Fred R. Klenner from the 1940s through the 1970s. There is a strong advocacy movement for very high doses of vitamin C, yet there is an absence of large-scale, formal trials in the 10 to 200+ grams per day range.

The single repeatable side effect of oral megadose vitamin C is a mild laxative effect if the practitioner attempts to consume too much too quickly. In the United States and Canada, a tolerable upper intake level (UL) was set at 2,000 mg/day, citing this mild laxative effect as the reason for establishing the UL.[1] However, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) reviewed the safety question in 2006 and reached the conclusion that there was not sufficient evidence to set a UL for vitamin C.[18] The Japan National Institute of Health and Nutrition reviewed the same question in 2010 and also reached the conclusion that there was not sufficient evidence to set a UL.[19]

About 70–90% of vitamin C is absorbed by the body when taken orally at normal levels (30–180 mg daily). Only about 50% is absorbed from daily doses of 1 gram (1,000 mg). Even oral administration of megadoses of 3g every four hours cannot raise blood concentration above 220 micromol/L.[20]

Relative deficiency hypothesis

Humans and other species that cannot synthesize their own vitamin C carry a mutated and ineffective form of the enzyme L-gulonolactone oxidase, the fourth and last step in the ascorbate-producing machinery. In the anthropoids lineage, this mutation likely occurred 40 to 25 million years ago. The three surviving enzymes continue to produce the precursors to vitamin C, but the absence of the fourth enzyme means the process is never completed, and the body ultimately disassembles the precursors.

In the 1960s, the Nobel-Prize-winning chemist Linus Pauling, after contact with Irwin Stone,[21] began actively promoting vitamin C as a means to greatly improve human health and resistance to disease. His book How to Live Longer and Feel Better was a bestseller and advocated taking more than 10 grams per day orally, thus approaching the amounts released by the liver directly into the circulation in other mammals: an adult goat, a typical example of a vitamin C-producing animal, will manufacture more than 13,000 mg of vitamin C per day in normal health and much more when stressed.

Matthias Rath is a controversial German physician who worked with and published two articles discussing the possible relationship between lipoprotein and vitamin C with Pauling.[22][23] He is an active proponent and publicist for high-dose vitamin C. Pauling's and Rath's extended theory states that deaths from scurvy in humans during the Pleistocene, when vitamin C was scarce, selected for individuals who could repair arteries with a layer of cholesterol provided by lipoprotein(a), a lipoprotein found in vitamin C-deficient species.[24]

Stone[25] and Pauling[9] believed that the optimum daily requirement of vitamin C is around 2,300 milligrams for a human requiring 2,500 kcal per day. For comparison, the FDA's recommended daily allowance of vitamin C is only 90 milligrams.[1]

Adverse effects

Although sometimes considered free of toxicity, there are in fact known side effects from vitamin C intake, and it has been suggested that intravenous injections should require "a medical environment and trained professionals."[26]

For example, a genetic condition that results in inadequate levels of the enzyme glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) can cause sufferers to develop hemolytic anemia after using intravenous vitamin C treatment.[27] The G6PD deficiency test is a common laboratory test.

Because oxalic acid is produced during metabolism of vitamin C, hyperoxaluria can be caused by intravenous administration of ascorbic acid.[26] Vitamin C administration may also acidify the urine and could promote the precipitation of kidney stones or drugs in the urine.[26]

Although vitamin C can be well tolerated at doses well above what government organizations recommend, adverse effects can occur at doses above 3 grams per day. The common "threshold" side effect of megadoses is diarrhea. Other possible adverse effects include increased oxalate excretion and kidney stones, increased uric acid excretion, systemic conditioning ("rebound scurvy"), preoxidant effects, iron overload, reduced absorption of vitamin B12 and copper, increased oxygen demand, and acid erosion of the teeth when chewing vitamin C tablets.[1] In addition, one case has been noted of a woman who received a kidney transplant followed by high-dose vitamin C and died soon afterwards as a result of calcium oxalate deposits that destroyed her new kidney. Her doctors concluded that high-dose vitamin C therapy should be avoided in patients with kidney failure.[28]

Overdose

As discussed previously, vitamin C generally exhibits low toxicity. The LD50 (the dose that will kill 50% of a population) is generally accepted to be 11,900 milligrams (11.9 grams) per kilogram in rat populations.[29] The American Association of Poison Control Centers has reported zero deaths from vitamin C toxicity.[30]

Interactions

Pharmaceuticals designed to reduce stomach acid, such as the proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs), are among the most widely sold drugs in the world. One PPI, omeprazole (Prilosec), has been found to lower the bioavailability of vitamin C by 12% after 28 days of treatment, independent of dietary intake. The probable mechanism of vitamin C reduction, intragastric pH elevated into alkalinity, would apply to all other PPI drugs, though not necessarily to doses of PPIs low enough to keep the stomach slightly acidic.[31] In another study, 40 mg/day of omeprazole lowered the fasting gastric vitamin C levels from 3.8 to 0.7 µg/mL.[32] Aspirin may also inhibit the absorption of vitamin C.[33][34]

Regulation

There are regulations in most countries that limit the claims regarding treatment of disease that can be placed on food and dietary supplement product labels. For example, claims of therapeutic effect with respect to the treatment of any medical condition or disease are prohibited by the United States Food and Drug Administration even if the substance in question has gone through well conducted clinical trials with positive outcomes. Claims are limited to Structure:Function phrasing ("Helps maintain a healthy immune system") and the following notice is mandatory on food and dietary supplement product labels that make these types of health claims: These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.[35]

Research

Cancer

The use of vitamin C in high doses as a treatment for cancer was promoted by Linus Pauling, based on a 1976 study published with Ewan Cameron which reported intravenous vitamin C significantly increased lifespans of patients with advanced cancer.[36][2] This trial was criticized by the National Cancer Institute for being designed poorly, and three subsequent trials conducted at the Mayo Clinic could not replicate the results.[2][37]

Preliminary clinical trials in humans have shown that it is unlikely to be a "miracle pill" for cancer and more research is necessary before any definitive conclusions about efficacy can be reached.[26] A 2010 review of 33 years of research on vitamin C to treat cancer stated "we have to conclude that we still do not know whether Vitamin C has any clinically significant antitumor activity. Nor do we know which histological types of cancers, if any, are susceptible to this agent. Finally, we don't know what the recommended dose of Vitamin C is, if there is indeed such a dose, that can produce an anti-tumor response."[37]

The American Cancer Society has stated, "Although high doses of vitamin C have been suggested as a cancer treatment, the available evidence from clinical trials has not shown any benefit."[2]

Burns

One clinical trial used high intravenous doses of vitamin C (66 mg/kg/hour for 24 hours, for a total dose of around 110 grams) after severe burn injury,[38] but despite being described as promising, it has not been replicated by independent institutions and thus is not a widely accepted treatment.[39] Based on that study, the American Burn Association (ABA) considers high-dose ascorbic acid an option to be considered for adjuvant therapy in addition to the more accepted standard treatments.[40]

Cardiac effects

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common cardiac rhythm disturbance associated with oxidative stress. Four meta-analyses have concluded that there is strong evidence that consuming 1–2 g/day of vitamin C before and after cardiac operations can decrease the risk of post-operative AF.[41][42][43][44] However, five randomized studies did not find any such benefit in the United States, so that the benefit was restricted to less wealthy countries.[44][45]

Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction

Exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (EIB) indicates acute narrowing of the airways as a result of vigorous exercise. EIB seems to be caused by the loss of water caused by increased ventilation, which may lead to the release of mediators such as histamine, prostaglandins, and leukotrienes, all of which cause bronchoconstriction. Vitamin C participates in the metabolism of these mediators and might thereby influence EIB.[46] A meta-analysis showed that 0.5 to 2 g/day of vitamin C before exercise decreased EIB by half.[47]

Endothelial function

A meta-analysis showed a significant positive effect of vitamin C on endothelial function. Benefit was found of vitamin C in doses ranging from 0.5 to 4 g/day, whereas lower doses from 0.09 to 0.5 g/day were not effective. No effect on endothelial function was seen in healthy volunteers or healthy smokers.[48]

Common cold

A frequently cited meta-analysis calculated that various doses of vitamin C (daily doses under 0.2 grams were excluded) do not prevent the common cold in the general community, although 0.25 to 1 g/day of vitamin C halved the incidence of colds in people under heavy short-term physical stress.[49] Another meta-analysis calculated that, in children, 1–2 g/day vitamin C shortened the duration of colds by 18%, and in adults 1–4 g/day vitamin C shortened the duration of colds by 8%.[49] There is evidence of linear dose-dependency in the effect of vitamin C on common cold duration up to 6–8 g/day.[50] As noted above, there is an absence of large-scale, formal trials in the 10 to 200+ grams per day range, so no information is available for these higher dosages. Additionally, the cited studies of larger daily doses of vitamin C do not take into account the fast excretion rate of vitamin C at gram-level doses, which makes it necessary to give the total daily amount in smaller, more frequent doses to maintain higher plasma levels.[51] As of 2014, at least 16 studies had found that vitamin C supplements did not prevent the common cold and had minimal effect at best in shortening cold lengths.[3]

See also

- Vitamin C

- Intravenous ascorbic acid

- Megavitamin therapy

- Orthomolecular medicine

- Uric acid

References

- Institute of Medicine (2000). "Vitamin C". Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium, and Carotenoids. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. pp. 95–185. ISBN 978-0-309-06935-9. Retrieved 2017-09-01.

- "Vitamin C". American Cancer Society.

- Barret, Steven, MD (September 14, 2014). "The Dark Side of Linus Pauling's Legacy". www.quackwatch.org. Archived from the original on September 4, 2018. Retrieved 2018-12-18.

- Bad Science, Ben Goldacre

- Trick Or Treatment, Simon Singh & Edzard Ernst

- David Gorski, Science Based Medicine, 18 Aug 2008

- Gropper SS, Smith JL, Grodd JL (2004). Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism (4th ed.). Belmont, CA. US: Thomson Wadsworth. pp. 260–275.

- Yeom CH, Jung GC, Song KJ (2007). "Changes of terminal cancer patients' health-related quality of life after high dose vitamin C administration". J. Korean Med. Sci. 22 (1): 7–11. doi:10.3346/jkms.2007.22.1.7. PMC 2693571. PMID 17297243.

- Pauling L (1970). "Evolution and the need for ascorbic acid". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 67 (4): 1643–1648. Bibcode:1970PNAS...67.1643P. doi:10.1073/pnas.67.4.1643. PMC 283405. PMID 5275366.

- Pollock, J. I.; Mullin, R. J. (1987). "Vitamin C biosynthesis in prosimians: Evidence for the anthropoid affinity of Tarsius". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 73 (1): 65–70. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330730106. PMID 3113259.

- R. Eric Miller; Murray E. Fowler (2014-07-31). Fowler's Zoo and Wild Animal Medicine, Volume 8. p. 389. ISBN 9781455773992. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- Jenness R, Birney E, Ayaz K (1980). "Variation of l-gulonolactone oxidase activity in placental mammals". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 67 (2): 195–204. doi:10.1016/0305-0491(80)90131-5.

- Martinez del Rio C (July 1997). "Can passerines synthesize vitamin C?". The Auk. 114 (3): 513–16. doi:10.2307/4089257. JSTOR 4089257.

- Vitamin and mineral requirements in human nutrition (PDF) (2nd ed.). World Health Organization. 2004. p. 138. ISBN 978-9241546126. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- Levy, Thomas (2011). Primal Panacea. MedFox Publishing. p. 352. ISBN 978-0983772804.

- Harri Hemilä (January 2006). "Do vitamins C and E affect respiratory infections?" (PDF). University of Helsinki. Retrieved 2007-02-21.

- "Vitamin C (Ascorbic Acid)". University of Maryland Medical Center. April 2002. Archived from the original on 2005-12-31. Retrieved 2007-02-19.

- "Tolerable Upper Intake Levels For Vitamins And Minerals" (PDF). European Food Safety Authority. 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 16, 2016.

- Dietary Reference Intakes for Japanese 2010: Water-Soluble Vitamins Journal of Nutritional Science and Vitaminology 2013(59):S67-S82.

- "Office of Dietary Supplements - Vitamin C". ods.od.nih.gov. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- "My Love Affair with Vitamin C" (PDF).

- Rath M, Pauling L (1990). "Immunological evidence for the accumulation of lipoprotein(a) in the atherosclerotic lesion of the hypoascorbemic guinea pig". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 87 (23): 9388–9390. Bibcode:1990PNAS...87.9388R. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.23.9388. PMC 55170. PMID 2147514.

- Rath M, Pauling L (1990). "Hypothesis: lipoprotein(a) is a surrogate for ascorbate". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 87 (16): 6204–6207. Bibcode:1990PNAS...87.6204R. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.16.6204. PMC 54501. PMID 2143582.

- Rath M, Pauling L (1992). "A unified theory of human cardiovascular disease leading the way to the abolition of this disease as a cause for human mortality" (PDF). Journal of Orthomolecular Medicine. 7 (1): 5–15.

- Stone, Irwin (1972). The Healing Factor: Vitamin C Against Disease. Grosset and Dunlap. ISBN 978-0-448-11693-8. OCLC 3967737.

- Verrax J, Calderon PB (December 2008). "The controversial place of vitamin C in cancer treatment". Biochem. Pharmacol. 76 (12): 1644–52. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2008.09.024. PMID 18938145.

- Rees; Kelsey, Richards (March 1993). "Acute haemolysis induced by high dose ascorbic acid in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency". British Medical Journal. 306 (6881): 841–2. doi:10.1136/bmj.306.6881.841. PMC 1677333. PMID 8490379.

- Nankivell, BJ; Murali KM (2008). "Renal failure from vitamin C after transplantation". The New England Journal of Medicine. 358 (4): e4. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm070984. PMID 18216350.

- "Safety (MSDS) data for ascorbic acid". Oxford University. October 9, 2005. Retrieved 2007-02-21.

- "American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC) - Annual Report". aapcc.org.

- E. B. Henry, A. Carswell, A. Wirz, V. Fyffe & K. E. L. Mccoll (September 2005). "Proton pump inhibitors reduce the bioavailability of dietary vitamin C". Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 22 (6): 539–45. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02568.x. PMID 16167970. S2CID 23976667.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - C. Mowat; A. Carswell; A. Wirz; K.E. McColl (April 1999). "Omeprazole and dietary nitrate independently affect levels of vitamin C and nitrite in gastric juice". Gastroenterology. 116 (4): 813–22. doi:10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70064-8. PMID 10092303.

- Loh HS, Watters K & Wilson CW (1 November 1973). "The Effects of Aspirin on the Metabolic Availability of Ascorbic Acid in Human Beings". J Clin Pharmacol. 13 (11): 480–486. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1973.tb00203.x. PMID 4490672. Archived from the original on 16 March 2007. Retrieved 31 July 2007.

- Basu TK (1982). "Vitamin C-aspirin interactions". Int J Vitam Nutr Res Suppl. 23: 83–90. PMID 6811490.

- "Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994". Food and Drug Administration.

- Cameron E, Pauling L (October 1976). "Supplemental ascorbate in the supportive treatment of cancer: Prolongation of survival times in terminal human cancer". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 73 (10): 3685–3689. Bibcode:1976PNAS...73.3685C. doi:10.1073/pnas.73.10.3685. PMC 431183. PMID 1068480.

- Cabanillas, F (2010). "Vitamin C and cancer: what can we conclude--1,609 patients and 33 years later?". Puerto Rico Health Sciences Journal. 29 (3): 215–7. PMID 20799507.

- Berger MM (October 2006). "Antioxidant micronutrients in major trauma and burns: evidence and practice". Nutr Clin Pract. 21 (5): 438–49. doi:10.1177/0115426506021005438. PMID 16998143.

- Greenhalgh DG (2007). "Burn resuscitation". J Burn Care Res. 28 (4): 555–65. doi:10.1097/bcr.0b013e318093df01. PMID 17665515. S2CID 3683908.

- Pham TN, Cancio LC, Gibran NS (2008). "American Burn Association practice guidelines burn shock resuscitation". J Burn Care Res. 29 (1): 257–66. doi:10.1097/BCR.0b013e31815f3876. PMID 18182930. S2CID 3694150.

- Baker, W. L; Coleman, C. I (2016). "Meta-analysis of ascorbic acid for prevention of postoperative atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 73 (24): 2056–2066. doi:10.2146/ajhp160066. PMID 27806938.

- Polymeropoulos, Evangelos; Bagos, Pantelis; Papadimitriou, Maria; Rizos, Ioannis; Patsouris, Efstratios; Toumpoulis, Ioannis (2016). "Vitamin C for the Prevention of Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation after Cardiac Surgery: A Meta-Analysis". Advanced Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 6 (2): 243–50. doi:10.15171/apb.2016.033. PMC 4961983. PMID 27478787.

- Hu, Xiaolan; Yuan, Linhui; Wang, Hongtao; Li, Chang; Cai, Junying; Hu, Yanhui; Ma, Changhua (2017). "Efficacy and safety of vitamin C for atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: A meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis of randomized controlled trials". International Journal of Surgery. 37: 58–64. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.12.009. PMID 27956113.

- Hemilä, Harri; Suonsyrjä, Timo (2017). "Vitamin C for preventing atrial fibrillation in high risk patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. 17 (1): 49. doi:10.1186/s12872-017-0478-5. PMC 5286679. PMID 28143406.

- Hemilä, Harri (2017). "Publication bias in meta-analysis of ascorbic acid for postoperative atrial fibrillation". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 74 (6): 372–373. doi:10.2146/ajhp160999. hdl:10138/312602. PMID 28274978.

- Hemilä, Harri (2014). "The effect of vitamin C on bronchoconstriction and respiratory symptoms caused by exercise: A review and statistical analysis". Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology. 10 (1): 58. doi:10.1186/1710-1492-10-58. PMC 4363347. PMID 25788952.

- Hemilä, Harri (2013). "Vitamin C may alleviate exercise-induced bronchoconstriction: A meta-analysis". BMJ Open. 3 (6): e002416. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002416. PMC 3686214. PMID 23794586.

- Ashor, Ammar W; Lara, Jose; Mathers, John C; Siervo, Mario (2014). "Effect of vitamin C on endothelial function in health and disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". Atherosclerosis. 235 (1): 9–20. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.04.004. PMID 24792921.

- Hemilä, Harri; Chalker, Elizabeth (2013). "Vitamin C for preventing and treating the common cold". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 (1): CD000980. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000980.pub4. PMC 1160577. PMID 23440782.

- Hemilä, Harri (2017). "Vitamin C and Infections". Nutrients. 9 (4): 339. doi:10.3390/nu9040339. PMC 5409678. PMID 28353648.

- Hickey S, Roberts H (27 September 2005). "Misleading Information on the Properties of Vitamin C". PLOS Medicine. 2 (9): e307. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020307. PMC 1236801. PMID 16173838.

External links

- Quackwatch article critical of megadosing for cold prevention, Charles W. Marshall, Ph.D. Accessed 2016-06-02.