Isopropyl alcohol

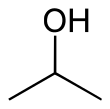

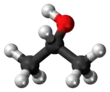

Isopropyl alcohol (IUPAC name propan-2-ol and also called isopropanol or 2-propanol) is a colorless, flammable organic compound (chemical formula CH3CHOHCH3) with a strong alcoholic odor.[9] As an isopropyl group linked to a hydroxyl group, it is the simplest example of a secondary alcohol, where the alcohol carbon atom is attached to two other carbon atoms. It is a structural isomer of propan-1-ol and ethyl methyl ether.

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Propan-2-ol[1] | |||

| Other names | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

Beilstein Reference |

635639 | ||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.601 | ||

Gmelin Reference |

1464 | ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID |

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 1219 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| (CH3)2CHOH | |||

| Molar mass | 60.096 g/mol | ||

| Appearance | Colorless liquid | ||

| Odor | Pungent alcoholic odor | ||

| Density | 0.786 g/cm3 (20 °C) | ||

| Melting point | −89 °C (−128 °F; 184 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 82.6 °C (180.7 °F; 355.8 K) | ||

| Miscible with water | |||

| Solubility | Miscible with benzene, chloroform, ethanol, diethyl ether, glycerol; soluble in acetone | ||

| log P | −0.16[3] | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 16.5[4] | ||

| −45.794·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

Refractive index (nD) |

1.3776 | ||

| Viscosity | 2.86 cP at 15 °C 1.96 cP at 25 °C[5] 1.77 cP at 30 °C[5] | ||

Dipole moment |

1.66 D (gas) | ||

| Pharmacology | |||

| D08AX05 (WHO) | |||

| Hazards | |||

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |||

Main hazards |

Flammable, mildly toxic[6] | ||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| |||

| Danger | |||

Hazard statements |

H225, H302, H319, H336 | ||

Precautionary statements |

P210, P261, P305+P351+P338 | ||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | Open cup: 11.7 °C (53.1 °F; 284.8 K) Closed cup: 13 °C (55 °F) | ||

Autoignition temperature |

399 °C (750 °F; 672 K) | ||

| Explosive limits | 2–12.7% | ||

Threshold limit value (TLV) |

980 mg/m3 (TWA), 1225 mg/m3 (STEL) | ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose) |

|||

LC50 (median concentration) |

|||

LCLo (lowest published) |

| ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 400 ppm (980 mg/m3)[8] | ||

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 400 ppm (980 mg/m3), ST 500 ppm (1225 mg/m3)[8] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

2000 ppm[8] | ||

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | |||

| Related compounds | |||

Related alcohols |

1-Propanol, ethanol, 2-butanol | ||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Isopropyl alcohol (data page) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |||

It is used in the manufacture of a wide variety of industrial and household chemicals and is a common ingredient in products such as antiseptics, disinfectants, hand sanitizer and detergents. Well over one million tonnes is produced worldwide annually.

Properties

Isopropyl alcohol is miscible in water, ethanol, and chloroform as, like these compounds, isopropyl is a polar molecule. It dissolves ethyl cellulose, polyvinyl butyral, many oils, alkaloids, and natural resins.[10] Unlike ethanol or methanol, isopropyl alcohol is not miscible with salt solutions and can be separated from aqueous solutions by adding a salt such as sodium chloride. The process is colloquially called salting out, and causes concentrated isopropyl alcohol to separate into a distinct layer.[11]

Isopropyl alcohol forms an azeotrope with water, which gives a boiling point of 80.37 °C (176.67 °F) and a composition of 87.7% by mass (91% by volume) isopropyl alcohol. Alcohol mixtures have depressed melting points.[11] It has a slightly bitter taste, and is not safe to drink.[11][12]

Isopropyl alcohol becomes increasingly viscous with decreasing temperature and freezes at −89 °C (−128 °F).

Isopropyl alcohol has a maximal absorbance at 205 nm in an ultraviolet-visible spectrum.[13][14]

Reactions

Isopropyl alcohol can be oxidized to acetone, which is the corresponding ketone. This can be achieved using oxidizing agents such as chromic acid, or by dehydrogenation of isopropyl alcohol over a heated copper catalyst:

- (CH3)2CHOH → (CH3)2CO + H2

Isopropyl alcohol is often used as both solvent and hydride source in the Meerwein-Ponndorf-Verley reduction and other transfer hydrogenation reactions. Isopropyl alcohol may be converted to 2-bromopropane using phosphorus tribromide, or dehydrated to propene by heating with sulfuric acid.

Like most alcohols, isopropyl alcohol reacts with active metals such as potassium to form alkoxides that are called isopropoxides. With titanium tetrachloride, isopropyl alcohol reacts to give titanium isopropoxide:

- TiCl4 + 4 (CH3)2CHOH → Ti(OCH(CH3)2)4 + 4 HCl

This and similar reactions are often conducted in the presence of base.

The reaction with aluminium is initiated by a trace of mercury to give aluminium isopropoxide.[15]

History

In 1920, Standard Oil first produced isopropyl alcohol by hydrating propene. Isopropyl alcohol was oxidized to acetone for the preparation of cordite, a smokeless, low explosive propellant.[16]

Production

In 1994, 1.5 million tonnes of isopropyl alcohol were produced in the United States, Europe, and Japan.[17] It is primarily produced by combining water and propene in a hydration reaction or by hydrogenating acetone.[17][18] There are two routes for the hydration process and both processes require that the isopropyl alcohol be separated from water and other by-products by distillation. Isopropyl alcohol and water form an azeotrope, and simple distillation gives a material that is 87.9% by mass isopropyl alcohol and 12.1% by mass water.[19] Pure (anhydrous) isopropyl alcohol is made by azeotropic distillation of the wet isopropyl alcohol using either diisopropyl ether or cyclohexane as azeotroping agents.[17]

Biological

Small amounts of isopropyl alcohol are produced in the body in diabetic ketoacidosis.[20]

Indirect hydration

Indirect hydration reacts propene with sulfuric acid to form a mixture of sulfate esters. This process can use low-quality propene, and is predominant in the USA. These processes give primarily isopropyl alcohol rather than 1-propanol, because adding water or sulfuric acid to propene follows Markovnikov's rule. Subsequent hydrolysis of these esters by steam produces isopropyl alcohol, by distillation. Diisopropyl ether is a significant by-product of this process; it is recycled back to the process and hydrolyzed to give the desired product.[17]

- CH3CH=CH2 + H2O (CH3)2CHOH

Direct hydration

Direct hydration reacts propene and water, either in gas or liquid phase, at high pressures in the presence of solid or supported acidic catalysts. This type of process usually requires higher-purity propylene (> 90%).[17] Direct hydration is more commonly used in Europe.

Hydrogenation of acetone

Isopropyl alcohol can be prepared via the hydrogenation of acetone; however, this approach involves an extra step compared to the above methods, as acetone is itself normally prepared from propene via the cumene process.[17] IPA cost is primarily driven by raw material (acetone or propylene) cost. A known issue is the formation of MIBK and other self-condensation products. Raney nickel was one of the original industrial catalysts, modern catalysts are often supported bimetallic materials.

Uses

In 1990, 45,000 metric tonnes of isopropyl alcohol were used in the United States, mostly as a solvent for coatings or for industrial processes. In that year, 5400 metric tonnes were used for household purposes and in personal care products. Isopropyl alcohol is popular in particular for pharmaceutical applications,[17] due to its low toxicity. Some isopropyl alcohol is used as a chemical intermediate. Isopropyl alcohol may be converted to acetone, but the cumene process is more significant.[17]

Solvent

Isopropyl alcohol dissolves a wide range of non-polar compounds. It evaporates quickly and the typically available grades tend to not leave behind oil traces when used as a cleaning fluid unlike some other common solvents. It is also relatively non-toxic. Thus, it is used widely as a solvent and as a cleaning fluid, especially for situations where there can be oils or other oil based residues which would not be easily cleaned with water, conveniently evaporating and (depending on water content, and other potential factors) posing less of a risk of corrosion or rusting than plain water. Together with ethanol, n-butanol, and methanol, it belongs to the group of alcohol solvents.

Isopropyl alcohol is commonly used for cleaning eyeglasses, electrical contacts, audio or video tape heads, DVD and other optical disc lenses, removing thermal paste from heatsinks on CPUs and other IC packages.

Intermediate

Isopropyl alcohol is esterified to give isopropyl acetate, another solvent. It reacts with carbon disulfide and sodium hydroxide to give sodium isopropylxanthate, a herbicide and an ore flotation reagent.[21] Isopropyl alcohol reacts with titanium tetrachloride and aluminium metal to give titanium and aluminium isopropoxides, respectively, the former a catalyst, and the latter a chemical reagent.[17] This compound may serve as a chemical reagent in itself, by acting as a dihydrogen donor in transfer hydrogenation.

Medical

Rubbing alcohol, hand sanitizer, and disinfecting pads typically contain a 60–70% solution of isopropyl alcohol or ethanol in water. Water is required to open up membrane pores of bacteria, which acts as a gateway for isopropyl alcohol. A 75% v/v solution in water may be used as a hand sanitizer.[22] Isopropyl alcohol is used as a water-drying aid for the prevention of otitis externa, better known as swimmer's ear.[23]

Inhaled isopropyl alcohol can be used for treating nausea in some settings by placing a disinfecting pad under the nose.[24]

Early uses as an anesthetic

Although isopropyl alcohol can be used for anesthesia, its many negative attributes or drawbacks prohibit this use. Isopropyl alcohol can also be used similarly to ether as a solvent[25] or as an anesthetic by inhaling the fumes or orally. Early uses included using the solvent as general anesthetic for small mammals[26] and rodents by scientists and some veterinarians. However, it was soon discontinued, as many complications arose, including respiratory irritation, internal bleeding, and visual and hearing problems. In rare cases, respiratory failure leading to death in animals was observed.

Automotive

Isopropyl alcohol is a major ingredient in "gas dryer" fuel additives. In significant quantities, water is a problem in fuel tanks, as it separates from gasoline and can freeze in the supply lines at low temperatures. Alcohol does not remove water from gasoline, but the alcohol solubilizes water in gasoline. Once soluble, water does not pose the same risk as insoluble water, as it no longer accumulates in the supply lines and freezes but is dissolved within the fuel itself. Isopropyl alcohol is often sold in aerosol cans as a windshield or door lock deicer. Isopropyl alcohol is also used to remove brake fluid traces from hydraulic braking systems, so that the brake fluid (usually DOT 3, DOT 4, or mineral oil) does not contaminate the brake pads and cause poor braking. Mixtures of isopropyl alcohol and water are also commonly used in homemade windshield washer fluid.

Laboratory

As a biological specimen preservative, isopropyl alcohol provides a comparatively non-toxic alternative to formaldehyde and other synthetic preservatives. Isopropyl alcohol solutions of 70–99% are used to preserve specimens.

Isopropyl alcohol is often used in DNA extraction. A lab worker adds it to a DNA solution to precipitate the DNA, which then forms a pellet after centrifugation. This is possible because DNA is insoluble in isopropyl alcohol.

Safety

Isopropyl alcohol vapor is denser than air and is flammable, with a flammability range of between 2 and 12.7% in air. It should be kept away from heat and open flame.[27] Distillation of isopropyl alcohol over magnesium has been reported to form peroxides, which may explode upon concentration.[28][29] Isopropyl alcohol causes eye irritation[27] and is a potential allergen.[30][31] Wearing protective gloves is recommended.

Toxicology

Isopropyl alcohol, via its metabolites, is somewhat more toxic than ethanol, but considerably less toxic than ethylene glycol or methanol. Death from ingestion or absorption of even relatively large quantities is rare. Both isopropyl alcohol and its metabolite, acetone, act as central nervous system (CNS) depressants.[32] Poisoning can occur from ingestion, inhalation, or skin absorption. Symptoms of isopropyl alcohol poisoning include flushing, headache, dizziness, CNS depression, nausea, vomiting, anesthesia, hypothermia, low blood pressure, shock, respiratory depression, and coma.[32] Overdoses may cause a fruity odor on the breath as a result of its metabolism to acetone.[33] Isopropyl alcohol does not cause an anion gap acidosis, but it produces an osmolal gap between the calculated and measured osmolalities of serum, as do the other alcohols.[32]

Isopropyl alcohol is oxidized to form acetone by alcohol dehydrogenase in the liver[32] and has a biological half-life in humans between 2.5 and 8.0 hours.[32] Unlike methanol or ethylene glycol poisoning, the metabolites of isopropyl alcohol are considerably less toxic, and treatment is largely supportive. Furthermore, there is no indication for the use of fomepizole, an alcohol dehydrogenase inhibitor, unless co-ingestion with methanol or ethylene glycol is suspected.[34]

In forensic pathology, people who have died as a result of diabetic ketoacidosis usually have blood concentrations of isopropyl alcohol of tens of mg/dL, while those by fatal isopropyl alcohol ingestion usually have blood concentrations of hundreds of mg/dL.[20]

References

- Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry : IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. p. 631. doi:10.1039/9781849733069. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- "Alcohols Rule C-201.1". Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry (The IUPAC 'Blue Book'), Sections A, B, C, D, E, F, and H. Oxford: Pergamon Press. 1979.

Designations such as isopropanol, sec-butanol, and tert-butanol are incorrect because there are no hydrocarbons isopropane, sec-butane, and tert-butane to which the suffix "-ol" can be added; such names should be abandoned. Isopropyl alcohol, sec-butyl alcohol, and tert-butyl alcohol are, however, permissible (see Rule C-201.3) because the radicals isopropyl, sec-butyl, and tert-butyl do exist.

- "Isopropanol_msds". chemsrc.com. Archived from the original on 2020-03-10. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- Reeve, W.; Erikson, C. M.; Aluotto, P. F. (1979). "A new method for the determination of the relative acidities of alcohols in alcoholic solutions. The nucleophilicities and competitive reactivities of alkoxides and phenoxides". Can. J. Chem. 57 (20): 2747–2754. doi:10.1139/v79-444.

- Yaws, C.L. (1999). Chemical Properties Handbook. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-073401-2.

- Isopropyl alcohol toxicity

- "Isopropyl alcohol". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0359". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- "Isopropanol". PubChem. Archived from the original on February 12, 2019. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- Doolittle, Arthur K. (1954). The Technology of Solvents and Plasticizers. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 628.

- The Merck Index (10th ed.). Rahway, NJ: Merck & Co. 1983. p. 749. ISBN 9780911910278.

- Logsden, John E.; Loke, Richard A. (1999). "Propyl Alcohols". In Jacqueline I. (ed.). Kirk- Concise of Chemical Technology (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 1654–1656. ISBN 978-0471419617.

- "Isopropyl Alcohol, , Suitable for Liquid Chromatography, Extract/, UV-Spectrophotometry". VWR International. Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- "UV Cutoff" (PDF). University of Toronto. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 October 2013. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- Ishihara, K.; Yamamoto, H. (2001). "Aluminum Isopropoxide". Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/047084289X.ra084. ISBN 0471936235.

- Wittcoff, M. M.; Green, H. A. (2003). Organic chemistry principles and industrial practice (1. ed., 1. reprint. ed.). Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. p. 4. ISBN 978-3-527-30289-5.

- Papa, A. J. "Propanols". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a22_173.

- Logsdon, John E.; Loke, Richard A. (December 4, 2000). "Isopropyl Alcohol". Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. Kirk‑Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi:10.1002/0471238961.0919151612150719.a01. ISBN 978-0471238966.

- CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 44th ed. pp. 2143–2184.

- Petersen, Thomas H.; Williams, Timothy; Nuwayhid, Naziha; Harruff, Richard (2012). "Postmortem Detection of Isopropanol in Ketoacidosis". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 57 (3): 674–678. doi:10.1111/j.1556-4029.2011.02045.x. ISSN 0022-1198. PMID 22268588. S2CID 21101240.

- "Sodium Isopropyl Xanthate, SIPX, Xanthate". 3DChem.com. Archived from the original on 2012-05-04. Retrieved 2012-06-17.

- "Guide to Local Production: WHO-recommended Handrub Formulations" (PDF). World Health Organization. August 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-05-19. Retrieved 2020-10-05.

- Otitis Externa (Swimmers Ear). Medical College of Wisconsin.

- Lindblad, Adrienne J.; Ting, Rhonda; Harris, Kevin (August 2018). "Inhaled isopropyl alcohol for nausea and vomiting in the emergency department". Canadian Family Physician. 64 (8): 580. ISSN 1715-5258. PMC 6189884. PMID 30108075.

- Burlage, Henry M.; Welch, H.; Price, C. W. (2006). "Pharmaceutical applications of isopropyl alcohol II. Solubilities of local anesthetics". Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association. 36 (1): 17–19. doi:10.1002/jps.3030360105. PMID 20285822.

- Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine (1922). Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine, Volume 19. p. 85. Archived from the original on 2021-12-20. Retrieved 2016-09-24.

- "Isopropanol". Sigma-Aldrich. 19 January 2012. Archived from the original on 17 January 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- Mirafzal, Gholam A.; Baumgarten, Henry E. (1988). "Control of peroxidizable compounds: An addendum". Journal of Chemical Education. 65 (9): A226. Bibcode:1988JChEd..65A.226M. doi:10.1021/ed065pA226.

- "Chemical safety: peroxide formation in 2-propanol". Chemical & Engineering News. 94 (31): 2. August 1, 2016. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- García-Gavín, Juan; Lissens, Ruth; Timmermans, Ann; Goossens, An (2011-06-17). "Allergic contact dermatitis caused by isopropyl alcohol: a missed allergen?". Contact Dermatitis. 65 (2): 101–106. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.01936.x. ISSN 0105-1873. PMID 21679194. S2CID 42577253.

- McInnes, A. (1973-02-10). "Skin reaction to isopropyl alcohol". British Medical Journal. 1 (5849): 357. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5849.357-c. ISSN 0007-1447. PMC 1588210. PMID 4265463.

- Slaughter RJ, Mason RW, Beasley DM, Vale JA, Schep LJ (2014). "Isopropanol poisoning". Clinical Toxicology. 52 (5): 470–8. doi:10.3109/15563650.2014.914527. PMID 24815348. S2CID 30223646.

- Kalapos, M. P. (2003). "On the mammalian acetone metabolism: from chemistry to clinical implications". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 1621 (2): 122–39. doi:10.1016/S0304-4165(03)00051-5. PMID 12726989.

- "Isopropyl alcohol poisoning". uptodate.com. Archived from the original on 2017-10-10. Retrieved 2017-10-10.

External links

- CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards - Isopropyl alcohol

- Environmental Health Criteria 103: 2-Propanol