Aarskog–Scott syndrome

| Aarskog–Scott syndrome / Aarskog Syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Faciodigitogenital syndrome (FGDY), faciogenital dysplasia, Aarskog disease, Scott Aarskog syndrome[1] | |

| Symptoms | Broad hands and feet, wide set eyes, low set ears, drooping lower lip[1] |

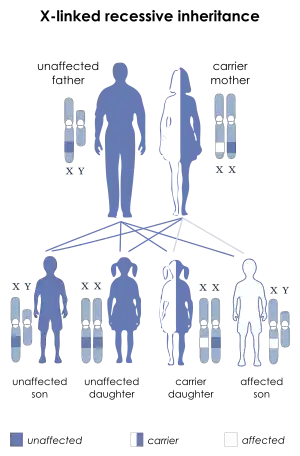

| Causes | Genetic (X-linked recessive)[1] |

| Deaths | 2018, two deaths one patient aged 66 years, another aged 62 also diagnosed with Non-Hodgkin lymphoma 2019 one death aged 54. All males from the same family. |

Aarskog–Scott syndrome is a rare disease inherited as X-linked and characterized by short stature, facial abnormalities, skeletal and genital anomalies.[2] This condition mainly affects males, although females may have mild features of the syndrome.[3][4]

Signs and symptoms

People with Aarskog–Scott syndrome often have distinctive facial features, such as widely spaced eyes (hypertelorism), a small nose, a long area between the nose and mouth (philtrum), and a widow's peak hairline. They frequently have mild to moderate short stature during childhood, but their growth usually catches up with that of their peers during puberty. Hand abnormalities are common in this syndrome and include short fingers (brachydactyly), curved pinky fingers (fifth finger clinodactyly), webbing of the skin between some fingers (cutaneous syndactyly), and a single crease across the palm. Other abnormalities in people with Aarskog–Scott syndrome include heart defects and a split in the upper lip (cleft lip) with or without an opening in the roof of the mouth (cleft palate).[3]

Most males with Aarskog–Scott syndrome have a shawl scrotum, in which the scrotum surrounds the penis instead of hanging below. Less often, they have undescended testes (cryptorchidism) or a soft out-pouching around the belly-button (umbilical hernia) or in the lower abdomen (inguinal hernia).[3]

The intellectual development of people with Aarskog–Scott syndrome varies widely. Some may have mild learning and behavior problems, while others have normal intelligence. In rare cases, severe intellectual disability has been reported.[3]

Genetics

Mutations in the FGD1 gene are the only known genetic cause of Aarskog-Scott syndrome. The FGD1 gene provides instructions for making a protein that turns on (activates) another protein called Cdc42, which transmits signals that are important for various aspects of development before and after birth.[3]

Mutations in the FGD1 gene lead to the production of an abnormally functioning protein. These mutations disrupt Cdc42 signaling, leading to the wide variety of abnormalities that occur in people with Aarskog-Scott syndrome.[3]

Only about 20 percent of people with this disorder have identifiable mutations in the FGD1 gene. The cause of Aarskog-Scott syndrome in other affected individuals is unknown.[3]

Pathophysiology

The Aarskog–Scott syndrome is due to mutation in the FGD1 gene. FGD1 encodes a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) that specifically activates Cdc42, a member of the Rho (Ras homology) family of the p21 GTPases. By activating Cdc42, FGD1 protein stimulates fibroblasts to form filopodia, cytoskeletal elements involved in cellular signaling, adhesion, and migration. Through Cdc42, FGD1 protein also activates the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling cascade, a pathway that regulates cell growth, apoptosis, and cellular differentiation.

Within the developing mouse skeleton, FGD1 protein is expressed in precartilaginous mesenchymal condensations, the perichondrium and periosteum, proliferating chondrocytes, and osteoblasts. These results suggest that FGD1 signaling may play a role in the biology of several different skeletal cell types including mesenchymal prechondrocytes, chondrocytes, and osteoblasts. The characterization of the spatiotemporal pattern of FGD1 expression in mouse embryos has provided important clues to the understanding of the pathogenesis of Aarskog–Scott syndrome.

It appears likely that the primary defect in Aarskog–Scott syndrome is an abnormality of FGD1/Cdc42 signaling resulting in anomalous embryonic development and abnormal endochondral and intramembranous bone formation.

Diagnosis

Genetic testing may be available for mutations in the FGDY1 gene. Genetic counseling is indicated for individuals or families who may carry this condition, as there are overlapping features with fetal alcohol syndrome.[5][4]

Other examinations or tests can help with diagnosis. These can include:

detailed family history

- conducting a detailed physical examination to document morphological features

- testing for genetic defect in FGDY1

- x-rays can identify skeletal abnormalities

- echo cardiogram can screen for heart abnormalities

- CT scan of the brain for cystic development

- X-ray of the teeth

- Ultrasound of abdomen to identify undescended testis[6]

Treatment

Similar to all genetic diseases Aarskog–Scott syndrome cannot be cured, although numerous treatments exist to increase the quality of life.[6]

Surgery may be required to correct some of the anomalies, and orthodontic treatment may be used to correct some of the facial abnormalities. Trials of growth hormone have been effective to treat short stature in this disorder.[7]

Prognosis

Some people may have some mental slowness, but children with this condition often have good social skills. Some males may have problems with fertility.[4]

History

The syndrome is named for Dagfinn Aarskog, a Norwegian pediatrician and human geneticist who first described it in 1970,[8] and for Charles I. Scott, Jr., an American medical geneticist who independently described the syndrome in 1971.[9]

References

- 1 2 3 "Aarskog syndrome". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 15 May 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ↑ "Aarskog-Scott syndrome". Genetics Home Reference. Archived from the original on 2017-12-21. Retrieved 2018-03-06.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 National Institutes of Health, Genetics Home Reference, Genetics Home. "Aarskog-Scott syndrome". Genetics Home Reference. Archived from the original on 2017-12-21. Retrieved 2017-11-09.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - 1 2 3 "Aarskog syndrome: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-11-09. Retrieved 2017-11-09.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ "Fetal Alcohol Syndrome: Guidelines for Referral and Diagnosis" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-06-11. Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- 1 2 "Aarskog Syndrome (AAS)". DoveMed. 2014. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ↑ Darendeliler F.; Larsson P.; Neyzi O.; et al. (October–November 2003). "Growth hormone treatment in Aarskog syndrome: analysis of the KIGS (Pharmacia International Growth Database) data". J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 16 (8): 1137–42. doi:10.1515/jpem.2003.16.8.1137. PMID 14594174.

- ↑ Aarskog D. (1970). "A familial syndrome of short stature associated with facial dysplasia and genital anomalies". J. Pediatr. 77 (5): 856–61. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(70)80247-5. PMID 5504078.

- ↑ Scott CI (1971). "Unusual facies, joint hypermobility, genital anomaly and short stature: a new dysmorphic syndrome". Birth Defects Orig. Artic. Ser. 7 (6): 240–6. PMID 5173168.

- Jones, Kenneth Lyons (2005). Smith's Recognizable Patterns of Human Malformation (6th ed.). Philadelphia: WB Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-2359-7.

- Orrico A.; Galli L.; Cavaliere ML.; et al. (2004). "Phenotypic and molecular characterisation of the Aarskog–Scott syndrome: a survey of the clinical variability in light of FGD1 mutation analysis in 46 patients". Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 12 (1): 16–23. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201081. PMID 14560308.

External links

- Aarskog–Scott syndrome Archived 2020-05-26 at the Wayback Machine, detailed up-to-date information in OMIM (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man)

- Aarskog's syndrome at Who Named It?

- The Aarskog Foundation Archived 2021-08-12 at the Wayback Machine

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|