Coffin–Lowry syndrome

| Coffin–Lowry syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

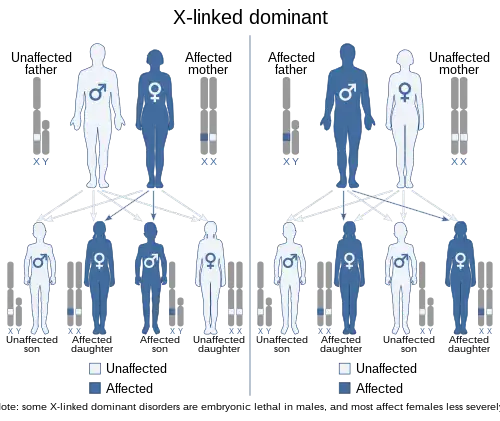

| X-linked dominant inheritence | |

Coffin–Lowry syndrome is a genetic disorder that is X-linked dominant and which causes severe mental problems sometimes associated with abnormalities of growth, cardiac abnormalities, kyphoscoliosis, as well as auditory and visual abnormalities.

Symptoms and signs

Symptoms of disease are more severe in males, who are generally diagnosed in early childhood. Children afflicted by CLS display cognitive disabilities of varying severity. Additional neuromuscular features include sleep apnea, muscular spasticity, progressive loss of muscle strength and tone leading to paraplegia or partial paralysis. Affected individuals are at elevated risk of stroke. Some patients experience stimulus-induced drop attacks (SIDAs, temporary paralytic episodes without loss of consciousness), triggered by unpredictable environmental stimuli (touch, scents, sounds, etc.). SIDA episodes become more frequent as the disease progresses, and become frequent around adolescence in males. Additional clinical physical features include small, soft hands with tapered fingers. Distinct facial architecture such as a flattened nose, widely separated and downward sloping eyes, a prominent forehead, and a wide mouth with large lips are reported as coincident facial features in patients with the disorder. Some individuals experience hearing loss. Others display kyphoscoliosis (multidirectional curvature of the spine) which can lead to difficulty with breathing and/or pulmonary hypertension. Cardiorespiratory complications may arise, which is why it is recommended that CLS patients undergo regular monitoring for spinal irregularities. Physical exams, CT imaging and X-ray imaging are standard methods of assessment.

Causes

The syndrome is caused by mutations in the RPS6KA3 gene.[1] This gene is located on the short arm of the X chromosome (Xp22.2). The RPS6KA3 gene makes a protein that is involved with signaling within cells. Researchers believe that this protein helps control the activity of other genes and plays an important role in the brain. The protein is involved in cell signaling pathways that are required for learning, the formation of long-term memories, and the survival of nerve cells. The protein RSK2 which is encoded by the RPS6KA3 gene is a kinase which phosphorylates some substrates like CREB and histone H3. RSK2 is involved at the distal end of the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway. Mutations in the RPS6KA3 disturb the function of the protein, but it is unclear how a lack of this protein causes the signs and symptoms of Coffin–Lowry syndrome. At this time more than 120 mutations have been found.[2] Some people with the features of Coffin–Lowry syndrome do not have identified mutations in the RPS6KA3 gene. In these cases, the cause of the condition is unknown.

This condition is inherited in an X-linked dominant pattern. A condition is considered X-linked if the gene that causes the disorder is located on the X chromosome (one of the two sex chromosomes). The inheritance is dominant if one copy of the altered gene is sufficient to cause the condition.

A majority of boys with Coffin–Lowry syndrome have no history of the condition in their families. These cases are caused by new mutations in the RPS6KA3 gene (de novo mutations). A new mutation means that neither parent has the altered gene, but the affected individual could pass it on to his children.

Genetics

Coffin–Lowry syndrome is an X-linked disorder resulting from loss-of-function mutations in the RPS6KA3 gene, which encodes RSK2 (ribosomal S6 kinase 2). Multiple mutations have been identified in RPS6KA3 that can give rise to the disorder, including missense mutations, nonsense mutations, insertions and deletions. Individuals with CLS rarely have affected parents, suggesting that most incidents arise from de novo mutations in the germline. The lack of an inheritance pattern may be due to the fact that affected individuals are unlikely to parent children. In 20–30% of cases, however, there is a family history of disease. In these cases, the disorder is typically inherited from the maternal parent. Because RPS6KA3 is located on the X chromosome, males (who possess only one copy of the X chromosome) display more severe symptoms than females. Affected females usually possess one mutated copy of the RPS6KA3 gene and one wild type copy. Random inactivation of one copy of the X chromosome in females mitigates the impact of possessing a mutant allele. Occasionally females are born with two mutated alleles. In these cases the symptoms are as severe as in males with the disease.[3]

Cell physiology

Mutations in the RPS6KA3 gene can result in expression of an RSK2 protein (ribosomal S6 kinase 2) with reduced or absent kinase function. RSK2 is a downstream component of the MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) cascade that is itself a kinase. RSK2 phosphorylates cellular proteins (including histone H3, and CREB), which regulate eukaryotic gene expression. In individuals with Coffin–Lowry syndrome, phosphorylation of transcriptional regulators is reduced due to the weakened activity of RSK2 kinase activity. RSK2 is normally activated by the ERK MAP kinase. Mutated RSK2 may be deficient for activation by ERK, or its kinase activity may be reduced despite activation by ERK. The most common mutation in RPS6KA3 is an early stop codon that fails to produce a functional protein, indicating that disease etiology most likely arises from loss-of-function effects. Substitution mutations (which alter a single amino acid) have also been shown to give rise to the disease. RSK2 is highly expressed in the brain, specifically in the neocortex, hippocampus, and Purkinje cells, all of which are involved in cognitive function and behavior. There is some experimental evidence that RSK2 regulates synaptic transmission and plasticity in neuronal cell types.[3]

Diagnosis

Affected individuals are often short in stature. Behavioral symptoms include aggression and depression, but these may be secondary to the emotional consequences of significant physical disabilities associated with the disorder.[4]

Coffin–Lowry patients may be affected by chewing and swallowing difficulties, for which there are diagnostic assessments. Among these are the Videofluoroscopic Swallowing Evaluation (VFSE), the Karaduman Chewing Performance Scale, and the Penetration Aspiration Scale (PAS) which is used to evaluate accidental aspiration of food particles.[5] The Pediatric Assessment Tool (PEDI-EAT-10) also includes measurement of severity of dysphagia (difficulty in swallowing). Molecular genetic testing can be used to confirm the genetic diagnosis of Coffin–Lowry syndrome or to assess pregnancy risk in affected families.

Symptoms table:

- Generally symptoms listed as "rare" are common in more severe cases.

| Symptom | Description | Frequency (male) | Frequency (female) | When first observed | Prognosis | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive disabilities | Mental retardation | Most severe | Ranges from severe to relatively normal intellect | Variable | ||

| Sleep apnea | Sleep disorder where breathing starts/stops, a lot of times the person will snore | More common | Less common | Progressive | CPAP machine | |

| Muscular spasticity | Stiff muscles | Most common | Less common | Muscle relaxers | ||

| Loss of muscle strength | Paraplegia or partial paralysis | Physical therapy | ||||

| Delayed speech | Limited vocabulary | Most common | Least common | Speech therapy | ||

| Cardiovascular complications | Mitral valve dysfunction, congestive heart failure | Most severe | Common | Premature death | ||

| Stroke | Interrupted blood flow to the brain | |||||

| Convulsions | Sudden, irregular body movements that can be violent | Common | Common | 1 year of age and onwards | Depending on severity can lead to death | Medications, such as valproate |

| Stimulus-induced drop attacks (SIDAs) | Instantaneous loss of muscle tone as a result of sudden unexpected tactile of auditory stimuli but without loss of consciousness | Rare but observed | Rare but observed | Adolescence | Progressive | Prescribed benzodiazepines |

| Small/soft/fleshy hands | More common | Less common | At birth | |||

| Tapered fingers | More common | Less common | At birth | |||

| Flattened nose | Most common | Least common but variable | Childhood | |||

| Widely separated/ downward sloping eyes | Most common | Least common but variable | At birth | |||

| Prominent forehead | Protruding forehead | Most common | Least common but variable | Early infancy | ||

| Wide mouth / large lips | Most severe | Least common but variable | 2 years of age | Progressive | ||

| Sensorineural deafness | Hearing Loss | Most common | Least common | No cure; can utilize cochlear implants or hearing aids | ||

| Kyphoscoliosis | Abnormal curvature of the spine in 2 planes, outward rounding of the spine | Most severe | Least common | Progressive | Severe cardiorespiratory compromise and ultimately death | Physical therapy |

| Short stature | Range of height is 115–158cm | Most common | Least common | Early childhood | ||

| Aggression | Violent behavior | Risperidone prescription | ||||

| Depression | Feelings of sadness | Very rare | Most severe | 20 years of age | Psychiatric therapy, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | |

| Difficulty swallowing | Difficult time swallowing | Common | Common | 3 years of age | Rehabilitation | |

| Difficulty chewing | Difficult time chewing | Common | Common | 3 years of age | Rehabilitation | |

| Coughing while eating | Coughing while eating | Common | Common | 3 years of age | Rehabilitation | |

| Long-lasting wheezing | Coughs accompanied with a whistling sound from the chest that lasts long term | Common | Common | 3 years of age | Rehabilitation | |

| Sputum | Coughing up saliva and mucus | Common | Common | 3 years of age | Rehabilitation | |

| Inability to ingest food | Inability to eat food easily | Common | Common | 3 years of age | Rehabilitation | |

Imaging studies

X-ray and neuroimaging studies may be helpful in confirming a diagnosis of Coffin–Lowry syndrome. Decreased ribosomal S6 kinase activity in cultured fibroblast or transformed lymphoblast cells from a male indicates Coffin–Lowry syndrome. Studies of enzyme activity can not be used to diagnose an affected female.

Molecular genetic testing on a blood specimen or cells from a cheek swab is available to identify mutations in the RSK2 gene. This testing can be used to confirm but not rule out the diagnosis of Coffin–Lowry syndrome because not all affected individuals have a detectable mutation.[6]

Treatment

There is no cure for Coffin–Lowry syndrome. Clinical objectives are centered on symptom management. Because stimulus-induced drop attacks (SIDAs) can result in physical harm to patients with the disorder, the use of medication to prevent or reduce the number of SIDA episodes is a safety priority. Physical precautionary measures have also been used to protect patients from injury, including the use of a helmet or a wheelchair. Because sudden excitement or fright can trigger a SIDA episode it is important to minimize exposure to startling stimuli. Medications prescribed include benzodiazepines (tranquilizers used to treat anxiety), valproate (used to manage epilepsy and bipolar disorder), and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (used to treat major depression). When affected individuals display aggressive or destructive behavior that could harm themselves or others, the antipsychotic medication risperidone may eventually be prescribed. It is recommended that spinal development be monitored regularly by X-ray and physical exams. Echocardiograms are recommended every 5-10 years to assess cardiac function and development. Families are encouraged to receive genetic counseling in order to understand and prepare to provide care for children affected by Coffin–Lowry syndrome.[4]

Prognosis

Lifespan may be significantly shortened in males with Coffin-Lowry syndrome. Patients may survive into their late twenties, but generally suffer from early mortality due to cardiac, respiratory, and post-operative complications. The progression of reduced cardiac functioning over time may necessitate surgical procedures to counteract mitral valve dysfunction, congenital heart disease, patent ductus arteriosus, and ventricular hypertrophy. Kyphoscoliosis may worsen over time and contribute to these pathologies.[3]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of CLS is uncertain due to the rarity of the disease, but CLS is estimated to affect between 1 in 50,000 and 1 in 100,000 people. Prenatal testing is available to test for CLS of an offspring if a family member has been diagnosed with CLS. [3]

History

Coffin–Lowry was first described by Grange S. Coffin (b. 1923) in 1966 and independently by Robert Brian Lowry (b. 1932) in 1971.[2][7][8] Dr. Temtamy showed that the cases represented a single syndrome in 1975.

In 1972, Peter G. Procopis and B. Turner published a case study on a family of four brothers with Coffin-Lowry Syndrome, with female relatives, specifically sisters, only possessing some mild deformities and abnormalities.[9] In 1975, Samia Temtamy reported eight patients from three different families displaying symptoms of Coffin-Lowry Syndrome, suggesting that the disorder is more common than believed and often goes underdiagnosed. On the basis of these reports, AG Hunter, Simone Gilgenkrantz, and ID Young established Coffin-Lowry Syndrome as an novel medical diagnosis and named it for the two doctors to originally describe its clinical symptoms. Additional case studies have since expanded the original list of clinical signs and symptoms. In 2002, Helen Fryssira and RJ Simensen identified a 3 base pair deletion in the gene encoding RSK2, which was the first report of the gene responsible for Coffin-Lowry.

Culture

The Coffin–Lowry Syndrome Foundation[10] acts as a clearinghouse for information on Coffin–Lowry syndrome and hosts a forum for affected families. The family matching program facilitates community building and resource sharing for recent diagnoses.[11]

The Coffin-Lowry Syndrome Foundation was created in 1991. The mission of the Foundation is to provide informational links, resources, and databases to families and patients dealing with the disease and enables them to communicate with one another. Families and patients can share their experiences and retrieve advice on the foundation’s online site as well as locate helpful services, telephone support, and day-to-day news on medical progress into understanding and treating those affected by Coffin-Lowry Syndrome. The symbol of the foundation is an apple, chosen for its representation of knowledge, feminine beauty, immortality, rebirth, and peace. The foundation provides a support network and source of hope for the families of patients with Coffin-Lowry Syndrome.

References

- ↑ Delaunoy JP, Dubos A, Marques Pereira P, Hanauer A (August 2006). "Identification of novel mutations in the RSK2 gene (RPS6KA3) in patients with Coffin–Lowry syndrome". Clin. Genet. 70 (2): 161–6. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00660.x. PMID 16879200. S2CID 31521326.

- 1 2 synd/3425 at Who Named It?

- 1 2 3 4 Marques Pereira, P., Schneider, A., Pannetier, S. et al. "Coffin–Lowry syndrome". European Journal of Human Genetics 18, 627–633 (2010). doi:10.1038/ejhg.2009.189

- 1 2 Rogers RC, Abidi FE. Coffin–Lowry Syndrome Archived 2021-03-08 at the Wayback Machine. 16 July 2002 [Updated 1 February 2018. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., editors. GeneReviews [Internet]. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington, Seattle.

- ↑ Kübra Şahan, A. (2019, December 23). "Chewing and Swallowing Training Program in Coffin-Lowry Syndrome" Archived 2021-08-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Coffin Lowry Syndrome - NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders)". RareDiseases.org. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ↑ Coffin GS, Siris E, Wegienka LC (1966). "Mental retardation with osteocartilaginous anomalies". Am. J. Dis. Child. 112 (3): 205–213. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1966.02090120073006.

- ↑ Lowry B, Miller JR, Fraser FC (June 1971). "A new dominant gene mental retardation syndrome. Association with small stature, tapering fingers, characteristic facies, and possible hydrocephalus". Am. J. Dis. Child. 121 (6): 496–500. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1971.02100170078009. PMID 5581017.

- ↑ McKusick, V. A., & Kniffin, C. L. (2019, November 11). COFFIN-LOWRY SYNDROME; CLS. Retrieved from https://www.omim.org/entry/303600 Archived 2021-02-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Home". www.clsf.info. Archived from the original on 2018-10-10. Retrieved 2021-01-29.

- ↑ "Coffin–Lowry Syndrome Foundation". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Archived from the original on 3 December 2016. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

Sources

This article incorporates public domain text from The U.S. National Library of Medicine Archived 2019-02-04 at the Wayback Machine and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Archived 2016-12-15 at the Wayback Machine.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

- GeneReviews/UW/NIH entry on Coffin–Lowry syndrome Archived 2010-04-11 at the Wayback Machine

- http://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/coffin-lowry-syndrome Archived 2020-08-14 at the Wayback Machine