Aicardi syndrome

| Aicardi syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Agenesis of corpus callosum with chorioretinal abnormality[1] | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| This condition is inherited in an X-linked dominant manner. | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

Aicardi syndrome is a rare genetic malformation syndrome characterized by the partial or complete absence of a key structure in the brain called the corpus callosum, the presence of retinal abnormalities, and seizures in the form of infantile spasms.[2]

Aicardi syndrome is theorized to be caused by a defect on the X chromosome as it has thus far only been observed in girls or in boys with Klinefelter syndrome. Confirmation of this theory awaits the discovery of a causative gene. Symptoms typically appear before a baby reaches about 5 months of age.

Signs and symptoms

Children are most commonly identified with Aicardi syndrome before the age of five months. A significant number of girls are products of normal births and seem to be developing normally until around the age of three months, when they begin to have infantile spasms. The onset of infantile spasms at this age is due to closure of the final neural synapses in the brain, a stage of normal brain development. A number of tumors have been reported in association with Aicardi syndrome: choroid plexus papilloma (the most common), medulloblastoma, gastric hyperplastic polyps, rectal polyps, soft palate benign teratoma, hepatoblastoma, parapharyngeal embryonal cell cancer, limb angiosarcoma and scalp lipoma.[3]

Genetics

Almost all reported cases of Aicardi syndrome have been in girls. The few boys that have been identified with Aicardi syndrome have proved to have 47 chromosomes including an XXY sex chromosome complement, a condition called Klinefelter syndrome.

All cases of Aicardi syndrome are thought to be due to new mutations. No person with Aicardi syndrome is known to have transmitted the X-linked gene responsible for the syndrome to the next generation.

Diagnosis

Aicardi syndrome is typically characterized by the following triad of features - however, one of the "classic" features being missing does not preclude a diagnosis of Aicardi Syndrome, if other supporting features are present.[4]

- Partial or complete absence of the corpus callosum in the brain (agenesis of the corpus callosum);

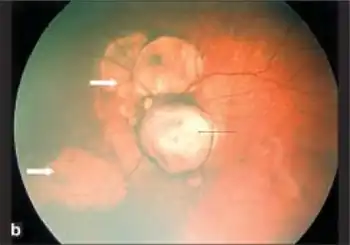

- Eye abnormalities known as "lacunae" of the retina that are quite specific to this disorder; optic nerve coloboma; and

- The development in infancy of seizures that are called infantile spasms.

Other types of defects of the brain such as microcephaly, polymicrogyria, porencephalic cysts and enlarged cerebral ventricles due to hydrocephalus are also common in Aicardi syndrome.

Treatment

Treatment of Aicardi syndrome primarily involves management of seizures and early/continuing intervention programs for developmental delays.Additional comorbidities and complications sometimes seen with Aicardi syndrome include porencephalic cysts and hydrocephalus, and gastro-intestinal problems. Treatment for porencephalic cysts and/or hydrocephalus is often via a shunt or endoscopic fenestration of the cysts, though some require no treatment. Placement of a feeding tube, fundoplication, and surgeries to correct hernias or other gastrointestinal structural problems are sometimes used to treat gastro-intestinal issues.

Prognosis

The prognosis varies widely from case to case, depending on the severity of the symptoms. However, almost all people reported with Aicardi syndrome to date have experienced developmental delay of a significant degree, typically resulting in mild to moderate to profound intellectual disability. The age range of the individuals reported with Aicardi syndrome is from birth to the mid-40s. There is no cure for this syndrome.

Epidemiology

Worldwide prevalence of Aicardi syndrome is estimated at several thousand, with approximately 900 cases reported in the United States.[5]

History

This disorder was first recognized as a distinct syndrome in 1965 by Jean Aicardi, a French pediatric neurologist and epileptologist.[6][4]

References

- ↑ RESERVED, INSERM US14-- ALL RIGHTS. "Orphanet: Aicardi syndrome". www.orpha.net. Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ↑ Rosser, Tena (1 October 2003). "Aicardi Syndrome". Archives of Neurology. 60 (10): 1471–3. doi:10.1001/archneur.60.10.1471. PMID 14568821.

- ↑ Sijmons, Rolf H (2008). "Encyclopaedia of tumour-associated familial disorders. Part I: from AIMAH to CHIME syndrome". Hereditary Cancer in Clinical Practice. 6 (1): 22–57. doi:10.1186/1897-4287-6-1-22. PMC 2735164. PMID 19706204.

- 1 2 Aicardi, Jean (January 1999). "Aicardi Syndrome: Old and New Findings" (PDF). International Pediatrics. 14 (1): 5–8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-01-21. Retrieved 2021-07-06.

- ↑ Kroner, Barbara L.; Preiss, Liliana R.; Ardini, Mary-Anne; Gaillard, William D. (29 January 2008). "New Incidence, Prevalence, and Survival of Aicardi Syndrome From 408 Cases". Journal of Child Neurology. 23 (5): 531–535. doi:10.1177/0883073807309782. PMID 18182643. S2CID 28004201.

- ↑ Aicardi J, Lefebvre J, Lerique-Koechlin A. A new syndrome: spasm in flexion, callosal agenesis, ocular abnormalities. Electroenceph Clin Neurophysiol 1965; 19: 609–610

External links

- GeneReviews/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on Aicardi Syndrome

- OMIM entries on Aicardi syndrome Archived 2021-08-27 at the Wayback Machine

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|