1957–1958 influenza pandemic

| 1957–1958 influenza pandemic | |

|---|---|

| Disease | Influenza |

| Virus strain | Strains of A/H2N2 |

| Location | Worldwide |

| First reported | Guizhou, China[1] |

| Date | 1957–1958 |

Deaths | 1–4 million (estimates) [2][3] |

| Influenza (Flu) |

|---|

|

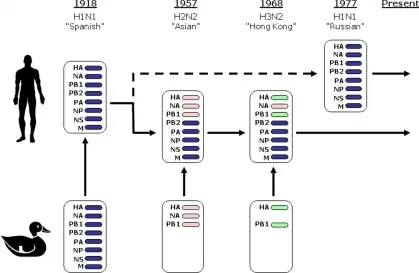

The 1957–1958 Asian flu pandemic was a global pandemic of influenza A virus subtype H2N2 that originated in Guizhou in Southern China.[1][4][2] The number of excess deaths caused by the pandemic is estimated to be 1–4 million around the world (1957–1958 and probably beyond), making it one of the deadliest pandemics in history.[2][3][5][6][7] A decade later, a reassorted viral strain H3N2 further caused the Hong Kong flu pandemic (1968–1969).[8]

History

Origin and outbreak in China

The first cases were reported in Guizhou of southern China, in 1956[9][10] or in early 1957.[1][4][11][12] Observers within China noted an epidemic beginning in the third week of February in western Guizhou, between its capital Guiyang and the city of Qujing in neighbouring Yunnan province.[12] They were soon reported in Yunnan in late February or early March 1957.[12][13] By the middle of March, the flu had spread all over China.[12][14]

The People's Republic of China was not a member of the World Health Organization at the time (not until 1981[15]), and did not inform other countries about the outbreak.[14] The United States CDC, however, contradicting most records, states that the flu was "first reported in Singapore in February 1957".[16]

In late 1957, a second wave of the flu took place in Northern China, especially in rural areas.[14] In the same year, as response to the epidemic, the Chinese government established the Chinese National Influenza Center (CNIC), which soon published a manual on influenza in 1958.[14][17]

Outbreak in other areas

.jpg.webp)

On 17 April 1957, The Times reported that "an influenza epidemic has affected thousands of Hong Kong residents".[18] The same day The New York Times reported that local press estimated at least 250,000 persons were receiving treatment by that time, out of the colony's total population of about 2.5 million.[19] The recent influx of about 700,000 refugees from mainland China had intensified authorities' fears of epidemics and fires due to crowded conditions,[19] and according to a report received by the US Influenza Information Center on 3 May, the disease was said to be occurring mainly among these refugees.[20]

By the end of the month (or as early as February[16][21]), Singapore also experienced an outbreak of the new flu, which peaked in mid-May with 680 deaths.[22] The only National Influenza Center reporting data to the World Health Organization for the southeast-Asian region in 1957 was located in Singapore,[23] and thus the country was the first to notify the WHO on 4 May about an extensive outbreak of the flu which "appeared to have been introduced from Hong Kong".[12][20] By the end of May, the outbreak had spread across Mainland Southeast Asia and also involved Indonesia, the Philippines, and Japan.[12] In Taiwan, 100,000 were affected by mid-May.[24]

India suffered a million cases by June.[24] In late June, the pandemic reached the United Kingdom.[18]

By June 1957, it reached the United States, where it initially caused few infections.[25] Some of the first people affected were US Navy personnel at destroyers docked at Newport Naval Station and new military recruits elsewhere.[26] The first wave peaked in October and affected mainly children who recently returned to school after summer break. The second wave, in January and February 1958, was more pronounced among elderly people and so was more fatal.[25][27]

United States

Background

Since the 1918 pandemic, epidemiological infrastructure in the US had expanded considerably. The Armed Forces Epidemiological Board and its Commission on Influenza were established in 1941, marking the beginning of the Armed Forces' involvement in the control of influenza.[28] Among other activities, the Board maintained surveillance of influenza-like illness around the world, operating 176 stations by 1957.[29] The Commission on Influenza also conducted studies into vaccination, which was considered "the only really effective control measure available in combating influenza".[28]

The Communicable Disease Center (today the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) was formed in 1946 initially for the control of malaria within military installations in the southeastern US. In light of developing Cold War–era concerns over biological warfare, the Epidemic Intelligence Service was created in 1951 at the CDC as a combined service and training program in the field of applied epidemiology, with the purpose of investigating certain disease outbreaks, among other activities.[30]

The 1950s were a tumultuous time in public health in the US. After the incidence of poliomyelitis in the US reached a peak in 1952,[31] the first vaccine against it was licensed in 1955. Its rollout that year was marred by an incident in April involving Cutter Laboratories, one of the manufacturers of the inactivated vaccine, in which some lots of its vaccine actually contained live virus, resulting in tens of thousands of vaccine-derived infections and tens of cases of paralytic polio.[32] Oveta Culp Hobby, the first secretary of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, quit in July (though she claimed that her intention to resign went back to January and was so that she could care for her ailing husband, former Governor of Texas William P. Hobby).[33] Marion B. Folsom replaced her on 1 August.

This vaccine incident reportedly strained the relationship between Hobby and the Surgeon General, Leonard A. Scheele. Hobby relegated the entirety of federal responsibility in the vaccine program to the Surgeon General, not the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare. After being sworn in for a third term in April 1956, with no public indication of his intentions, Scheele resigned on 1 August to work at a pharmaceutical company.[34] On 8 August, his successor, Leroy E. Burney, was sworn in as the eighth Surgeon General.[35]

On 20 January 1957, Dwight D. Eisenhower and Richard Nixon were sworn in for a second term as president and vice president respectively.

National response

The notion that an influenza pandemic was developing in the Far East first occurred to American microbiologist Maurice Hilleman, who was alarmed by pictures of those affected by the virus in Hong Kong that were published in The New York Times, on 17 April 1957.[19][36] Hilleman was then head of the Department of Respiratory Diseases at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. He immediately sent for virus samples from patients in the Far East,[36] and, on 12 May, the first isolate was sent out to the vaccine manufacturers as soon as they all arrived in the US.[37]

The Office of the Surgeon General became aware of the situation in Asia on 20 May.[38] Burney was out of the country at the time, representing the US at the Tenth World Health Assembly in Geneva.[39][40] The Deputy Surgeon General, W.P. Dearing, spread the word and established special liaison with the National Institutes of Health on Burney's behalf.[38]

On 22 May, after working "around the clock" for the last five days, Hilleman's team reported that the viruses isolated in the Far East were type A but antigenically quite distinct from previously known strains.[41] Hilleman predicted an epidemic would strike the US when schools reopened in the fall.[36] The microbiologist was thereafter instrumental in stimulating the development of the pandemic vaccine.

The day after Hilleman's announcement, the Division of Foreign Quarantine began to monitor travelers from the Far East for signs of respiratory illness.[42] All Epidemic Intelligence Service officers and all relevant personnel at the CDC were alerted of the priority of investigating cases and outbreaks of influenza-like disease at that time.[43]

The Public Health Service formally began its participation in the national effort against the flu on 28 May. The Surgeons General of the military called a meeting with the Service to discuss the control of the novel influenza. The disease was noted for its mild presentation though high rates of attack in various settings. It was the opinion of those at the meeting that the virus was already in the US, but no epidemic was expected until the fall. It was recommended that the Department of Defense purchase about 3 million doses of monovalent vaccine targeting the pandemic virus. The Commission on Influenza was asked to propose the composition of the polyvalent vaccine to be used as well.[38]

The following day, the director of the National Institutes of Health, Justin M. Andrews, having consulted with CDC Director Robert J. Anderson, submitted a memo that recommended, among other items, that the monovalent pandemic vaccine needed for the Department of Defense be licensed, that state epidemiologists be alerted to watch for outbreaks of influenza-like illness, that EIS officers immediately investigate any reported outbreak, and that "the role of influenza vaccine as a public health measure be carefully studied...".[38]

On 31 May, Dearing reflected on the 1918 pandemic and how new strains of influenza emerge, "presumably by mutation", which may spark another pandemic at any time. In writing, he indicated his support for a mass immunization program, saying that, if epidemiologists did find the present situation "unusual or almost unique", then the burden of proof would shift to opponents of such a program. He asked the principal staff officers to explore whether "the investment of the few million dollars necessary" to organize an immunization campaign would be advisable, if the situation indeed justified it.[38]

World Health Organization's response

The 1957–1958 pandemic was the first influenza pandemic to occur since the creation of the World Health Organization in 1947. Memories of the 1918 pandemic were still ever-present.[44] In recognition of the worldwide threat of epidemic influenza, the WHO launched its Global Influenza Programme in 1947 with the establishment of the World Influenza Centre at the National Institute for Medical Research in London.[45] This eventually gave rise to the Global Influenza Surveillance Network in 1952 to facilitate global scientific collaboration and fulfil the objectives of the programme.[46]

In 1957, China was not a member of the WHO, and thus it was not a part of its influenza surveillance network. Therefore, it took several weeks, if not months, for the news of an outbreak to reach the WHO, when the virus had already spread into Hong Kong and then to Singapore. This fact would be lamented repeatedly after the pandemic, and it was taken as reinforcement of the importance of a "truly worldwide" network of epidemiological surveillance.[47][48][45]

Following this delay, things then "moved swiftly".[48] After receiving the report out of Singapore in early May, the WHO reported on the developing outbreak for the first time in its Weekly Epidemiological Record published on 10 May.[20] Within three weeks laboratories around the world had concluded that the cause of these epidemics was a new variant of influenza A.[48][49][50] This information was first reported in the Weekly Epidemiological Record for 29 May.[50]

On 14 June, the WHO declared that attempts at large-scale quarantine were "as costly as they are ineffective", instead recommending only that acute cases be isolated. It reiterated that all reports it had received emphasized the mildness of the disease in most cases, with the very few deaths having occurred mainly in elderly victims suffering from chronic bronchitis.[51]

The need for a single, consistent name for the novel virus became clear as it continued to spread and became more commonly discussed.[52] Up to this point, the causative agent had mostly been called "Far East influenza virus"[53] or "Far East strain (influenza virus)"[54][55] or even "Oriental flu",[56] though "Asian influenza" had been used before.[57] On 11 July, the question was finally taken up at an informal meeting of scientists during the Fourth International Poliomyelitis Congress in Geneva. There it was agreed that "Asian influenza" was a "descriptive and appropriate" name for the "contemporary manifestation of the ancient disease",[38] as the term "Far East" was considered "not exact as to geographical location".[58]

On 23 July, the WHO issued a circular letter advising that surplus vaccine be made available to poorer countries at the "lowest economic price".[38]

On 16 August, William J. Tepsix, commander of Pennsylvania's Veterans of Foreign Wars in the United States, sent a letter to United Nations Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold demanding an investigation into whether the virus had been released by the Soviet Union or China.[59] It is not clear if the UN or the WHO ever responded to Tepsix's letter. However, US Surgeon General Leroy E. Burney would later dismiss this notion on 26 August in response to a similar question raised by the press.[60]

On 11 October, the WHO announced that the virus had spread to all populated parts of the world aside from "a few islands or territories having no contact with the outside world".[61]

Following the main phase of the pandemic in 1957, the WHO reflected on its performance as part of its review of the first ten years of the organization in 1958. It concluded that "the WHO influenza programme fulfilled the major task allotted to it", which allowed "many parts of the world to organize health services to meet the threat and for some countries to attempt to protect priority groups by vaccination". However, it acknowledged that had its influenza surveillance network been "truly worldwide", as it would repeatedly lament it was not, then preparations could have begun two months earlier.[45]

Vaccine

Background

In December 1942, Dr. Thomas Francis, Jr., and his colleagues on the United States Armed Forces' Commission on Influenza (including Jonas Salk, future developer of the inactivated polio vaccine) began a series of key studies into the use of inactivated influenza virus vaccines, which for the first time demonstrated the protective effect of such vaccines against infection.[62] Similar studies into their efficacy and safety continued until 1945,[63] when the first inactivated virus vaccine entered the market for commercial use.[64] In the fall of that year and the spring of 1946, the entirety of the Armed Forces received the inactivated virus vaccine.[65]

During the winter of 1946–1947, a worldwide influenza epidemic occurred, an event that for some time was itself considered a pandemic due to its global distribution albeit low mortality.[66][67] Vaccines that had been effective during the 1943–1944 and 1944–1945 seasons suddenly failed during this epidemic.[68] It was found that the influenza A virus had undergone significant antigenic drift, resulting in a virus that was quite antigenically distinct, but not one of an entirely new subtype. This experience demonstrated the necessity to alter vaccine composition to match newly circulating strains.[69]

In the winter of 1950–1951, a severe influenza epidemic ravaged England and Wales, the number of weekly deaths at one point even surpassing that of the 1918 pandemic in Liverpool.[70] Public health experts in the US, fearing the implications of the outbreak on their country, decided to impose a challenge on themselves: to see how quickly the British virus could be imported into the US, its antigenic structure analyzed, and then incorporated into a new vaccine, if the virus were found to be distinct from preexisting strains. Upon receipt of the strains at the laboratories at Walter Reed Army Institute of Research and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which then sent samples to the vaccine manufacturers, the two government laboratories were able to produce the required 1 liter of vaccine of "acceptable potency, sterility, and safety" in three weeks; the manufacturers were soon to follow. The exercise was considered a success by those involved, but it was recognized that a repeat performance in the future might not be so likely without the same factors in their favor.[71] Out of this exercise came a list of recommended priority groups from the civilian occupational population to be inoculated in the event of an emergency.[38]

In 1954, the Armed Forces initiated routine annual vaccination against the flu, considered the "only really effective measure available in combating" the virus,[28] but the Public Health Service did not recommend a comparable regimen to the general public. This was based on the relatively short-lived demonstrated immunity of the vaccines and the lack of certainty that the strains used in the polyvalent vaccines then would be the cause of epidemics in the future. However, this policy would be reexamined in light of the pandemic three years later.[38]

Pandemic vaccine

After reading of the epidemic underway in Hong Kong, Maurice Hilleman immediately sent for samples of the virus from patients in the Far East,[36] which were collected in late April 1957 and received at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research before the middle of May.[37] The Division of Biologics Standards of the US Public Health Service released the first of the virus cultures, designated A/Jap/305/57, to vaccine manufacturers on 12 May 1957. An immediate issue encountered with the new variant was in choosing the isolate optimally adaptable to producing necessary virus growth in chick embryos. After study of the five isolates in total, it was concluded that none in particular would be chosen for production, but each manufacturer would use whichever isolate showed the best growth characteristics.[37]

Hilleman's team reported its finding of the antigenic novelty of the virus on 22 May after working "around the clock" for the last five days.[41] Hilleman predicted an epidemic would strike the US when schools reopened in the fall.[36]

The Public Health Service formally began its participation in the effort against the flu on 29 May with a meeting with the Surgeons General of the military. The nature of the disease was discussed, and it was recommended that the Department of Defense purchase about 3 million doses of monovalent vaccine targeting the pandemic virus. The Commission on Influenza was asked to propose the composition of the polyvalent vaccine to be used as well. The following day, Justin M. Andrews, Director of NIH, having consulted with CDC Director Robert J. Anderson, submitted a memo that recommended, among other items, that the monovalent pandemic vaccine needed for the Department of Defense be licensed.[38]

On the last day of May, reflecting upon the experience of the 1918 pandemic, Acting Surgeon General W.P. Dearing indicated his support for a mass immunization program, if epidemiologists were to find the present situation "unusual or almost unique", in which case the burden of proof would shift to opponents of such a program. He asked the principal staff officers of the Office of the Surgeon General to explore whether "the investment of the few million dollars necessary" to organize an immunization campaign would be advisable, if the situation indeed justified it.[38]

Vaccine production was underway before the start of June. After receiving its samples on 23 May, for example, Merck Sharp & Dohme had produced "laboratory quantities" of pandemic vaccine within two weeks.[72] Before the middle of June, the first experimental lots had been produced and promptly entered into testing at the National Institutes of Health, which was expected to take about two weeks.[71][72] The first 90 volunteers from among PHS personnel were inoculated with the experimental vaccine on 18 June.[56]

On 5 June, the Assistant to the Surgeon General called a meeting with representatives of the three bureaus of the Service. The associate director of NIH reported that the technical problem in the production of the monovalent vaccine had been resolved and that it could be ready in September, with a polyvalent vaccine including the novel strain ready a month later. He advised that certain groups receive the monovalent vaccine at the same time as the Armed Forces, basing his priorities on the list produced following the 1951 exercise. It was made clear that this would not require any additional funding. The deputy chief of the Bureau of State Services then recommended that the Surgeon General form an advisory council of public health officials, physicians, and the manufacturers; his vision was one of the Public Health Service advocating for mass inoculation, which would necessitate extra funds.[38]

The first meeting of the Advisory Committee on Influenza occurred on 10 June. One general finding of this meeting was that since limited data suggested the existing polyvalent vaccine was not protective against the novel variant, an effective monovalent vaccine should be produced immediately. Existing polyvalent vaccine should be utilized as otherwise recommended. Furthermore, the present situation did not yet justify establishing priorities for civilian use or considering any federal subsidy in producing the vaccine.[38] Following this meeting, Surgeon General Burney held a press conference, where he discussed the vaccine. He shared the Department of Defense's consideration of purchasing 4 million doses of the monovalent vaccine — enough to vaccinate the entire Armed Forces, estimated at 2.8 million. He made clear that production of the monovalent vaccine would occupy the manufacturers, and so they would not be able to produce both the monovalent and the polyvalent vaccines at the same time. He also shared the committee's recommendation that if only 4 million doses could be produced over the next six weeks, they should go to the Armed Forces.[72]

The second phase of the Public Health Service's Asian Influenza Program began with a meeting of technical representatives of the manufacturers with NIH on 12 June. The manufacturers were presented with the latest epidemiological information, including data on the virus isolates and their growth characteristics. Here each company's experience with the different strains used in production was also summarized, and they ultimately agreed to review their inventories and report a potential formula that would make best use of available materials.[38] This same day, the State of New York announced its plan to start a pilot project to produce pandemic vaccine, authorized by Governor W. Averell Harriman.[73]

On 20 June, an associate director of NIH laid out various alternatives for the course of the virus in the US and how to respond to each: an explosive outbreak before 1 September, with either continued low mortality or increased virulence (vaccination would not be possible, except for the use of limited polyvalent vaccine supplies and possible use in 1958); sporadic local activity during the summer with an explosive outbreak in the winter, again with low mortality (vaccinate priority groups) or increased virulence (maximize vaccine production, vaccination would be required, and priority groups would receive it first); or sporadic local activity during the summer with normal incidence in the winter (no recommendation of vaccination). It was generally agreed that the most likely outcome would be closer to the second possibility, with sporadic local activity during the summer with an epidemic in the fall or winter, with little increase in lethality. It was also clear then that the quantities of vaccine necessary for large-scale inoculation would not be ready until after the middle of August, but if the epidemic held off until the fall and winter, as was considered likely, it would be possible protect a significant part of the population. This framework was later presented to the Secretary Folsom of Health, Education, and Welfare on 24 June.[38]

On 26 June, Burney met with representatives of the American Medical Association to discuss the virus and how best to employ medical manpower against a serious epidemic. The vaccination situation was also discussed, as well as the variety of federal responses envisioned by the Service. Although it was emphasized that the present situation did not appear to justify large-scale orders or subsidization of production by the federal government, the parties agreed up a partnership between the Public Health Service and the American Medical Association with the purpose of public health education. It was recognized that the public had heard much about the novel virus but had not heard a thing about how to protect itself against it.[38][74]

In 1957, six pharmaceutical companies were licensed to manufacture influenza vaccine: Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Eli Lilly & Co., Parke, Davis & Co., Pitman-Moore Co., National Drug Company, and Lederle Laboratories.[75] As members of the pharmaceutical industry, they had participated in the effort since the day the Public Health Service sent them samples of the virus. Maurice Hilleman happened to be close to the industry,[76] and he helped secure the initial involvement of the manufacturers, going to them directly to spur development and avoiding "the bureaucratic red tape" that might typically forestall manufacture of new pharmaceutical products.[36] In the latter half of June, following a series of outbreaks of the novel virus aboard naval vessels docked on the East Coast,[77] the Department of Defense provided a significant stimulus to commercial production by placing an order for 2,650,000 ml of monovalent vaccine.[71]

After Merck's production of "laboratory quantities" of vaccine by early June and the product's entry into clinical trials in the middle of June, initial batches from four other manufacturers, including Pitman-Moore Co. and Eli Lilly & Co.,[78] were sent to NIH in early July.[79] By this time, Pitman-Moore had received a government contract for about half a million doses while Eli Lilly had not, though Lilly confirmed it would be moving ahead with production on a "preparedness basis".[78]

The Public Health Service announced the establishment of specifications in the manufacture of the pandemic vaccine, which were then sent to the manufacturers, on 10 July.[80] Service officials that day also met with the Executive Committee of the Association of State and Territorial Health Officers in Washington, D.C., where the flu situation was discussed. The officers agreed with the proposed PHS-AMA partnership to launch a public health education campaign, specifically one that urged vaccination against the flu. At this time, influenza vaccines had generally been used by large companies to protect their employees, but with the threat of a probable, large-scale outbreak, stimulating their broader use seemed advisable.[38]

With the middle of July came the need finally to make two key policy decisions: whether to recommend vaccination again the flu for the general public and whether to recommend to the manufacturers to continue production of the monovalent vaccine then intended only for military use or to recommend they shift to making a polyvalent vaccine incorporating the novel variant for use by the general public. As to the first question, such a recommendation was considered medically justified, but the necessary quantities of vaccine had never been produced so quickly. Beyond providing for its own employees and patients, PHS ruled out any purchasing of vaccine itself. To the end of ensuring adequate supply for the general public, Burney spoke to each of the manufacturers by telephone from 15 July through 19 July. They could see the need, "from the standpoint of public health", to vaccinate as much as one-third of the population, and given the predictions of an epidemic and the plans already being developed by public health officials, they agreed to make a sizable investment in vaccine production without any aid from the federal government.[38]

As to the second question, NIH believed that a polyvalent vaccine was preferable immunologically speaking, but the manufacturers were unsure they could produce large amounts of an effective polyvalent vaccine on the timeline envisioned. On the other hand, a monovalent vaccine would become preferable if the virus itself were to become significantly deadlier. Therefore, the wisest recommendation seemed to be for a monovalent vaccine for use by the general public once the needs of the Armed Forces had been satisfied.[38]

Burney ultimately made these decisions, but they were not necessarily set in stone. With the unpredictability of influenza well recognized, it was considered judicious to "hedge" any policy in favor of reducing a potential rise in mortality, were it to occur. The Division of Biologics Standards therefore outlined a set of facilities that could be used to shore up production if the situation worsened. A mandatory allocation system for distribution and appropriation of funds for the purchase of vaccine and for public vaccination clinics were considered feasible if circumstances ultimately justified them.[38]

The vaccine entered trials at Fort Ord on 26 July and Lowry Air Force Base on 29 July.[26]

At the beginning of August, PHS gave the go-ahead to the press to initiate its public health education campaign.[38] Burney met with press to warn of "the very definite probability" of a widespread epidemic in the fall or winter. He shared that the manufacturers had agreed to working "triple shifts", every day of the week, to produce 8 million doses by the middle of September, of which half would go to the Armed Forces. The ultimate target was 60 million doses by 1 February.[81] It was made clear that there would not be enough time to produce enough vaccine to inoculate a majority of the country before the flu season, but vaccination, as "the only known preventive" against the flu, was viewed as the best course of action. When asked about the potential for mass immunization programs like those against polio, Burney stated that these would be the states' responsibility, but he conceded that "you could probably get more immunized in a shorter period" that way. The principal reason against such a policy was, apparently, that "that isn't the ordinary way we do things in this country."[82]

On 2 August, representatives of the Armed Forces, the Veterans Administration, and PHS met to discuss the question of vaccine dosage. It was the opinion of the Office of the Surgeon General, upon review of studies thus far reported, that 1 cc (cubic centimeter) of monovalent vaccine, with a strength of 200 CCA units, would be "the most effective and practical dosage".[38] This was five times the strength of the pilot vaccine initially announced on 10 July.[83] This potency was selected in light of difficulties during the early-summer trials in obtaining high yields of the virus in embryonated eggs, with any strength greater than 200 CCA seeming unlikely.[71]

On 9 August, Burney recommended to the Office of the Surgeon General that export of the pandemic vaccine be controlled while supplies were limited.[38] The next day, PHS announced its plans for a "nationwide battle" against the anticipated flu outbreak that fall and winter. Beginning in September, a mass education campaign would call for the public to get vaccinated through various media such as the press, radio, and television.[84]

On 12 August, Burney sent individual letters to each of the manufacturers requesting their cooperation with PHS in a "voluntary system of equitable interstate allocations" of the pandemic vaccine while supplies remained limited. They all agreed.[38] This plan was later announced on 16 August, with the purpose of such a system being to ensure "an equitable availability of vaccine supplies throughout all parts of the country". The manufacturers were acknowledged as having "informally" shown a willingness to follow the system while vaccine remained scarce. In short, each state would receive shipments of a fraction of a lot of vaccine from each manufacturer equal to the proportion of that state's population to the population of the entire country. Burney emphasized that the Service "would not contemplate any allocation between public agency purchasers and commercial sales."[85]

The first lot of 502,000 doses of vaccines was released on 12 August.[42] Almost immediately, issues with allocation became glaringly obvious. In Washington, D.C., physicians reported of an intensely worried public, asking more about the "Asiatic flu" than any other epidemic disease that any could recall. They feared that such pressure might bring about a black market around the vaccine (though Daniel L. Finucane, Director of the District Department of Health, doubted such a possibility).[86] Nevertheless, Time reported that National Drug Co. and Lederle Laboratories had sent their initial doses to companies across the country, leaving it to them to distribute the shots, and that indeed individual doctors had begun vaccinating "favored patients".[87] At the same time, the NFL's Chicago Cardinals were able to announce that the entire team would be vaccinated against the flu.[88]

The pandemic vaccine became relevant for the Eisenhower administration not long after the first doses were released. White House Press Secretary James Hagerty would report that two doses had been sent to Secretary of the Interior Fred A. Seaton by PHS. However, Seaton decided beginning his inoculation was not necessary before his trip to Hawaii. On 21 August, a spokesperson for the Department of Agriculture had to deny the speculation that the use of millions of eggs necessary for vaccine production would "skyrocket" the price of eggs. That same day, President Eisenhower was asked whether he would receive the pandemic vaccine. He replied, "I am going to take it just as soon as ordinary people like I am can get it."[89]

Eisenhower later met with his chief economic advisor, Gabriel Hauge. On 22 August, Hauge was sent home ill.[90] That same day, Burney stated that the president was "an essential person" and should get vaccinated immediately, a recommendation with which Eisenhower's personal physician, Major General Howard McCrum Snyder, "agreed completely".[91] On 24 August, Burney made the pointed recommendation that those with a history of heart or lung conditions be vaccinated early.[90] (Eisenhower had suffered a heart attack in September 1955.) Notably, he assured Snyder that there was sufficient vaccine in the district to cover this priority group.[92] Finally, based on Burney's recommendation the preceding weekend,[90] Eisenhower was vaccinated on 26 August, the injection administered by Snyder.[92] Hagerty reported that all members of the White House who worked closely with the president would thereafter be vaccinated.[92]

That same week, the Association of State and Territorial Health Officers convened in Bethesda, Maryland, and Washington, D.C., beginning on 27 August for a two-day special meeting to discuss the pandemic response. Among other recommendations pertaining to preparing for a likely epidemic, the Committee on Vaccination Promotion outlined how such programs should be carried out and who should be prioritized for inoculation. The primary objective for any such program was considered "to prevent illness and death from epidemic influenza within the limits of available vaccine." The committee sided with PHS's informal agreement with the manufacturers that they participate in a "voluntary" system of interstate allocation. It was plainly acknowledged that "influenza vaccine is being manufactured and will becoming increasingly available but is not yet available for everyone"; therefore, PHS would recommend to civilian physicians that they prioritize those working in essential services maintaining the health of the community, those maintaining other basic services, and those considered to be at "special medical risk". It was stated that the pandemic vaccine had been approved for use in children as young as three months, with the following recommendations for administration: Children three months to five years of age would receive a two-dose regimen of 0.1 cc each, spaced over one to two weeks; children five to 12 years of age would receive a similar two-dose regimen but of 0.5 cc each; and children 13 years of age and older would receive the same dosage as for adults, a single, 1.0-cc injection. Finally, it was resolved that the two vaccination programs, that against polio and now that against influenza, "be continued as independent and parallel programs."[93]

The second lot of 562,610 doses was released on 28 August, bringing the total to 1,149,610 doses for both military and civilian use. Burney shared the expectation that, based on the current pace of production, it was possible that 80 to 85 million doses would be ready by 1 January, 20 million doses more and one month sooner than originally anticipated. The Armed Forces announced their intention to give two injections to each servicemember, and thus their order had increased from 4 million doses to over 7 million.[94]

Just as after release of the first batch of vaccine, issues with supply and allocation quickly became apparent yet again. Although authorities like the New York County Medical Society and wholesalers in Washington, D.C., made clear that vaccine would not be available for the public until September or even October,[95][96] there was still intense demand for the vaccine. A physician's secretary in the district reported in The Evening Star that her office was receiving "dozens" of calls every day from anxious patients. This was not helped by Burney's statement days before, that there was sufficient vaccine in the district to vaccinate those with heart and lung conditions, such as the president.[97] Even the State Department had not received any vaccine, and it was reportedly unknown when it would.[96] Interestingly, in contrast to the D.C. situation, doctors in New York City reported that they had been asked about the vaccine, but the pressure was nowhere near that for the Salk polio vaccine when it had been in short supply.[95]

On 31 August, a spokesperson for National Drug stated that D.C. physicians had been "very well taken care of" with respect to vaccine. Finucane, the district health director, immediately pushed back on this claim, saying that he knew of "no large shipments of the vaccine into Washington" and that those who had received any were "lucky". Meanwhile, the pharmaceutical company had been very responsive to the demands of industrial concerns such as Bell Telephone, E. I. duPont de Nemours & Co., Inc., and Pennsylvania Railroad.[98] One district physician decried this state of affairs as "grossly unfair";[98] similarly, Dr. I. Phillips Frohman, a former chairman within the American Medical Association, labeled it "criminal".[99] However, the company defended its distribution practices by asserting it was "trying to get as much of the vaccine out as possible."[98]

Ironically, The Star's reporting on National Drug's statement regarding vaccine supply and Finucane's pushback, with the headline "Doctors Here Receive Vaccine for Patients", seemed to stimulate demand even more, according to physicians. J. Hunter Stewart, chief of the Information Office of the Office of the Surgeon General, clarified that there was no federal priority system beyond PHS's recommendations that the vaccine be distributed equitably and that it first go to healthcare providers. He emphasized: "But you must remember that these are recommendations."[99]

This insistence upon the voluntary nature of vaccine allocation was not satisfying to all. On 3 September, Dr. Thomas E. Mattingly wrote into The Star to thank it for debunking National Drug's statement and to discuss the situation in general. He described PHS's establishment of a system of priorities as "very wise" but asserted that it was "not enough to panic the public and not provide dependable discipline and guarantee a system of priorities". He called on the federal government to "accept both responsibility and purposeful leadership" and PHS to seize every last dose of vaccine and distribute it itself. The government would also reimburse the companies "for the fair cost of all vaccine they have been urged to manufacture."[100] Others echoed this call for some "special action of one vague kind or another" by the federal government, just as had been advocated for during the early days of the Salk vaccine,[101] but such policies seemed doubtful with an administration that two years before had dismissed free polio shots for children as "socialized medicine by the back door".[102]

Aftermath

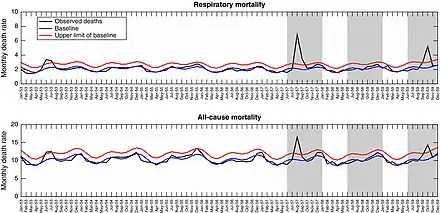

The number of deaths peaked the week ending 17 October, with 600 reported in England and Wales.[24] The vaccine was available in the same month in the United Kingdom.[18] Although it was initially available only in limited quantities,[27][18] its rapid deployment helped contain the pandemic.[25] Hilleman's vaccine is believed to have saved hundreds of thousands of lives.[103] Some predicted that the U.S. death toll would have reached 1 million without the vaccine that Hilleman called for.[104]

H2N2 influenza virus continued to be transmitted until 1968, when it transformed via antigenic shift into influenza A virus subtype H3N2, the cause of the 1968 influenza pandemic.[25][105]

Virology and clinical data

The strain of virus that caused the Asian flu pandemic, influenza A virus subtype H2N2, was a recombination of avian influenza (probably from geese) and human influenza viruses.[9][25] As it was a novel strain of the virus, the population had minimal immunity.[9][18] The reproduction number for the virus was around 1.8 and approximately two-thirds of infected individuals were estimated to have experienced clinical symptoms.[106]

It could cause pneumonia by itself without the presence of secondary bacterial infection. It caused many infections in children, spread in schools, and led to many school closures. However, the virus was rarely fatal in children and was most deadly in pregnant women, the elderly, and those with pre-existing heart and lung disease.[9]

Mortality estimates

In October 1957, Leroy Edgar Burney told The New York Times that the pandemic is mild and the case fatality rate (CFR) is below "two-thirds of 1 per cent", or less than 0.67%.[107] After the pandemic, information from 29 general practices in the UK estimated 2.3 deaths per 1,000 medically attended cases.[108] A survey based on randomly selected families in Kolkata, India, revealed that there were 1,055 deaths in 1,496,000 cases.[109] On the symposium of Asian influenza in 1958, a range of CFR from 0.01% to 0.33% was provided, most frequently in between 0.02% and 0.05%.[110] More recently, the World Health Organization estimated the CFR of Asian flu to be lower than 0.2%.[2] In the US pandemic preparedness plan, the CDC estimated the CFR of 1957 pandemic to be 0.1%.[111] The estimated CFR from first wave morbidity and excess mortality in Norway is in between 0.04% and 0.11%.[112] Other scholars estimated the CFR near 0.1%.[113][114][115]

The flu may have infected as many as or more people than the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, but the vaccine, improved health care, and the invention of antibiotics to manage opportunistic bacterial infections contributed to a lower mortality rate.[9]

Most estimates of excessive deaths due to the pandemic range from 1-4 million, some of which include years beyond 1958.[2][3][5][6][7][24][116] In particular, the attempt by the National Institutes of Health in 2016 attributed global mortality 1.1 million (0.7 to 1.5 million) excess deaths to the pandemic, including the year 1959.[5] This estimate of global burden has recently been adopted by the World Health Organization and US CDC.[6][116][117][118] The study also estimated the excess deaths in the first year of the pandemic, in 1957, to be 0.6 million (0.4 to 0.8 million).[5]

By country

- According to US CDC, two estimates of excess deaths, 70,000 and 116,000, are provided.[16][119] The first estimate refers to the 1957–1958 flu season while the higher estimate is multi-year totals from 1957 to 1960.[120][121][122]

- An estimated 33,000 deaths in the United Kingdom were attributed to the 1957–1958 flu outbreak.[9][105][123][124] The disease was estimated to have a 3% rate of complications and 0.3% mortality in the United Kingdom.[18]

- In West Germany, around 30,000 people died of the flu between September 1957 and April 1958.[125]

- According to the 2016 study in The Journal of Infectious Diseases, the highest excess mortality occurred in Latin America.[5]

Economic effects

The Dow Jones Industrial Average lost 15% of its value in the second half of 1957, and the U.S. experienced a recession.[124] In the United Kingdom, the government paid out £10,000,000 in sickness benefit, and some factories and mines had to close.[18] Many schools had to close in Ireland, including seventeen in Dublin.[126]

References

- 1 2 3 Pennington, T H (2006). "A slippery disease: a microbiologist's view". BMJ. 332 (7544): 789–790. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7544.789. PMC 1420718. PMID 16575087.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Pandemic Influenza Risk Management: WHO Interim Guidance" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2013. p. 19. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Past pandemics". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 2022-01-05. Retrieved 2022-01-08.

- 1 2 Tsui, Stephen KW (2012). "Some observations on the evolution and new improvement of Chinese guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of influenza". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 4 (1): 7–9. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2011.11.03. ISSN 2072-1439. PMC 3256544. PMID 22295158.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Viboud, Cécile; Simonsen, Lone; Fuentes, Rodrigo; Flores, Jose; Miller, Mark A.; Chowell, Gerardo (1 March 2016). "Global Mortality Impact of the 1957–1959 Influenza Pandemic". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. Oxford University Press. 213 (5): 738–745. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiv534. PMC 4747626. PMID 26908781.

- 1 2 3 "1957-1958 Pandemic (H2N2 virus)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2019-01-22. Archived from the original on 2019-01-30. Retrieved 2022-01-02.

- 1 2 Michaelis M, Doerr HW, Cinatl J (August 2009). "Novel swine-origin influenza A virus in humans: another pandemic knocking at the door". Medical Microbiology and Immunology. 198 (3): 175–183. doi:10.1007/s00430-009-0118-5. PMID 19543913. S2CID 20496301. Archived from the original on 2021-05-15. Retrieved 2021-10-23.

- ↑ "1968 Pandemic (H3N2 virus)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 22 January 2019. Archived from the original on 2019-01-30. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Clark, William R. (2008). Bracing for Armageddon?: The Science and Politics of Bioterrorism in America. Oxford University Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-19-045062-5. Archived from the original on 2022-12-30. Retrieved 2022-10-04.

- ↑ Perret, Robert. "LibGuides: Pandemics: Asian Flu (1956-1958)". University of Idaho. Archived from the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ↑ Peckham, Robert (2016). Epidemics in Modern Asia. Cambridge University Press. p. 276. ISBN 978-1-107-08468-1. Archived from the original on 2022-12-30. Retrieved 2022-10-04.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Symposium on the Asian Influenza Epidemic, 1957". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 51 (12): 1009–1018. 16 May 1958. doi:10.1177/003591575805101205. S2CID 68673011. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ↑ Strahan, Lachlan M. (October 1994). "An oriental scourge: Australia and the Asian flu epidemic of 1957". Australian Historical Studies. 26 (103): 182–201. doi:10.1080/10314619408595959.

- 1 2 3 4 Qin, Ying; et al. (2018). "History of influenza pandemics in China during the past century". Chinese Journal of Epidemiology (in 中文). 39 (8): 1028–1031. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2018.08.003. PMID 30180422. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021.

- ↑ "About WHO in China". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 2018-10-18. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 "1957-1958 Pandemic (H2N2 virus)". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 22 January 2019. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ↑ "国家流感中心发展历史 (History of CNIC)". CNIC (in 中文). Archived from the original on 21 July 2018. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jackson, Claire (1 August 2009). "History lessons: the Asian Flu pandemic". British Journal of General Practice. 59 (565): 622–623. doi:10.3399/bjgp09X453882. PMC 2714797. PMID 22751248.

- 1 2 3 "Hong Kong Battling Influenza Epidemic". The New York Times. 17 April 1957. p. 3. Archived from the original on 3 February 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Weekly Epidemiological Record, 1957, vol. 32, 19". Weekly Epidemiological Record. 19: 231–244. 10 May 1957. hdl:10665/211021. Archived from the original on 16 May 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022 – via IRIS.

- ↑ "Asian Flu (1957 Influenza Pandemic)". Sino Biological. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ↑ Ho, Olivia (19 April 2020). "Three times that the world coughed, and Singapore caught the bug". Straits Times. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ↑ Ziegler, T.; Mamahit, A.; Cox, N. J. (25 June 2018). "65 years of influenza surveillance by a World Health Organization-coordinated global network". Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. 12 (5): 558–565. doi:10.1111/irv.12570. PMC 6086847. PMID 29727518.

- 1 2 3 4 Honigsbaum, Mark (13 June 2020). "Revisiting the 1957 and 1968 influenza pandemics". The Lancet. 395 (10240): 1824–1826. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31201-0. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7247790. PMID 32464113.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "1957 flu pandemic". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 8 May 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- 1 2 Zeldovich, Lina (7 April 2020). "How America Brought the 1957 Influenza Pandemic to a Halt". JSTOR Daily. Archived from the original on 8 April 2020. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- 1 2 "Definition of Asian flu". MedicineNet. Archived from the original on 15 February 2004. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- 1 2 3 Griffin, Herschel E. (February 1958). "Influenza control in the Armed Forces". Public Health Reports. 73 (2): 145–148. doi:10.2307/4590064. JSTOR 4590064. PMC 1951629. PMID 13506000.

- ↑ Davenport, Fred M. (February 1958). "Role of the Commission on Influenza: Studies of epidemiology and prevention". Public Health Reports. 73 (2): 133–139. doi:10.2307/4590062. JSTOR 4590062. PMC 1951630. PMID 13505998.

- ↑ Thacker, Stephen B.; Dannenberg, Andrew L.; Hamilton, Douglas H. (1 December 2001). "Epidemic Intelligence Service of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 50 Years of Training and Service in Applied Epidemiology". American Journal of Epidemiology. 154 (11): 985–992. doi:10.1093/aje/154.11.985. PMID 11724713. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022 – via Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Nathanson, N.; Hall, W. J.; Thrupp, L. D.; Forester, H. (May 1957). "Surveillance of poliomyelitis in the United States in 1956". Public Health Reports. 72 (5): 381–392. PMC 2031288. PMID 13432107.

- ↑ Ruane, Michael E. (14 April 2020). "The tainted polio vaccine that sickened and fatally paralyzed children in 1955". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ↑ Lawrence, W. H. (14 July 1955). "Mrs. Hobby Quits As Welfare Head; Folsom Is Named". The New York Times. pp. 1, 13. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ↑ "Scheele Resigns As Health Chief". The New York Times. 30 June 1956. pp. 1, 18. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ↑ "Surgeon General Sworn". The New York Times. 9 August 1956. p. 17. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "1957 Asian Flu Pandemic". The History of Vaccines. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- 1 2 3 Andrews, Justin M. (February 1958). "Research programs on Asian influenza". Public Health Reports. 73 (2): 159–164. doi:10.2307/4590070. JSTOR 4590070. PMC 1951639. PMID 13506004.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Stewart, William H. (February 1958). "Administrative history of the Asian influenza program". Public Health Reports. 73 (2): 101–113. doi:10.2307/4590056. JSTOR 4590056. PMC 1951633. PMID 13505994.

- ↑ "Surgeon General Is Delegate". The New York Times. 4 May 1957. p. 44. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ↑ "Tenth World Health Assembly, Geneva, 7-24 May 1957: resolutions and decisions: plenary meetings: verbatim records: committees: minutes and reports: annexes". Official Records of the World Health Organization: 1–568. November 1957. hdl:10665/85686. Archived from the original on 13 October 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022 – via IRIS.

- 1 2 "Lab Identifies Flu Virus". The Evening Star. 23 May 1957. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- 1 2 "Asian strain of influenza A". Public Health Reports. 72 (9): 768–770. September 1957. PMC 2031381. PMID 13465935.

- ↑ Langmuir, Alexander D.; Pizzi, Mario; Trotter, William Y.; Dunn, Frederick L. (February 1958). "Asian influenza surveillance". Public Health Reports. 73 (2): 114–120. doi:10.2307/4590057. JSTOR 4590057. PMC 1951643. PMID 13505995.

- ↑ "Celebrating 70 years of the Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System". who.int. 15 March 2022. Archived from the original on 2022-03-18. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- 1 2 3 "The first ten years of the World Health Organization". 1958. hdl:10665/37089. Archived from the original on 2022-11-18. Retrieved 2022-10-04 – via IRIS.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Hay, Alan J; McCauley, John W (2018). "The WHO global influenza surveillance and response system (GISRS)—A future perspective". Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. 12 (5): 551–557. doi:10.1111/irv.12565. PMC 6086842. PMID 29722140.

- ↑ "The 1957 Influenza Epidemic". Chronicle of the World Health Organization. 11. September 1957 – via Internet Archive.

- 1 2 3 Gomes Candau, Marcolino Gomes (April 1958). "The work of WHO, 1957: annual report of the Director-General to the World Health Assembly and to the United Nations". Official Records of the World Health Organization. hdl:10665/85693. Archived from the original on 2022-05-16. Retrieved 2022-10-04 – via IRIS.

- ↑ "Lab Identifies Flu Virus". The Evening Star. 23 May 1957. p. A17. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- 1 2 "Weekly Epidemiological Record, 1957, vol. 32, 22". Weekly Epidemiological Record. 32: 267–278. 29 May 1957. hdl:10665/211045. Archived from the original on 16 May 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022 – via IRIS.

- ↑ "Asian Flu Called Mild". The New York Times. 15 June 1957. p. 7. Archived from the original on 20 March 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ↑ "What to Call New Flu Puzzles Health Aides". The New York Times. 16 August 1957. p. 21. Archived from the original on 20 March 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ↑ Meyer, H. M.; Hilleman, M. R.; Miesse, M. L.; Crawford, I. P.; Bankhead, A. S. (1 July 1957). "New Antigenic Variant in Far East Influenza Epidemic, 1957". Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 95 (3): 609–616. doi:10.3181/00379727-95-23306. PMID 13453522. S2CID 9648497. Archived from the original on 20 March 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022 – via SAGE.

- ↑ "Morbidity and mortality weekly report, Vol. 6, no. 22". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 6: 2–8. 7 June 1957. Archived from the original on 18 May 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022 – via CDC.

- ↑ "CDC influenza report no. 1". CDC Influenza Reports. 9 July 1957. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022 – via CDC.

- 1 2 "Oriental Flu Test On". The New York Times. 20 June 1957. p. 60. Archived from the original on 20 March 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ↑ "Asian Influenza". The New York Times. 9 June 1957. p. 170. Archived from the original on 20 March 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ↑ "CDC influenza report no. 6". CDC Influenza Reports. 25 July 1957. Archived from the original on 26 June 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022 – via CDC.

- ↑ "U.N. Asked to Inquire If Soviet Started Flu". The Evening Star. 16 August 1957. p. A2. Archived from the original on 20 March 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ↑ "'Planting' of Flu Germs by Reds Held Impossible". The Evening Star. 26 August 1957. p. A9. Archived from the original on 20 March 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ↑ "Asian Flu Is World-Wide". The New York Times. 12 October 1957. p. 21. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ↑ Francis, T. Jr.; Salk, J. E.; Pearson, H. E.; Brown, P. N. (July 1945). "Protective Effect of Vaccination Against Induced Influenza a 1". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 24 (4): 536–546. doi:10.1172/JCI101633. PMC 435485. PMID 16695243.

- ↑ Barberis, I.; Myles, P.; Ault, S. K.; Bragazzi, N. L.; Martini, M. (September 2016). "History and evolution of influenza control through vaccination: from the first monovalent vaccine to universal vaccines". Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene. 57 (3): E115–E120. PMC 5139605. PMID 27980374.

- ↑ Weir, J. P.; Gruber, M. F. (24 March 2016). "An overview of the regulation of influenza vaccines in the United States". Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. 10 (5): 354–360. doi:10.1111/irv.12383. PMC 4947948. PMID 27426005.

- ↑ Grabenstein, John D.; Pittman, Phillip R.; Greenwood, John T.; Engler, Renata J.M. (8 June 2006). "Immunization to Protect the US Armed Forces: Heritage, Current Practice, and Prospects". Epidemiologic Reviews. 28: 3–26. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxj003. PMID 16763072. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022 – via Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Monto, A. S.; Fukada, K. (17 August 2019). "Lessons From Influenza Pandemics of the Last 100 Years". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 70 (5): 951–957. doi:10.1093/cid/ciz803. PMC 7314237. PMID 31420670.

- ↑ Nelson, M. I.; Viboud, C.; Simonsen, L.; Bennett, R. T.; Griesemer, S. B.; St. George, K.; Taylor, J.; Spiro, D. J.; Sengamalay, N. A.; Ghedin, Elodie; Taubenberger, J. K. (29 February 2008). "Multiple Reassortment Events in the Evolutionary History of H1N1 Influenza A Virus Since 1918". PLOS Pathogens. 4 (2): e1000012. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000012. PMC 2262849. PMID 18463694.

- ↑ Kilbourne, E. D.; Smith, C.; Brett, I.; Pokorny, B. A.; Johansson, B.; Cox, N. (22 July 2002). "The total influenza vaccine failure of 1947 revisited: Major intrasubtypic antigenic change can explain failure of vaccine in a post-World War II epidemic". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (16): 10748–10752. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9910748K. doi:10.1073/pnas.162366899. PMC 125033. PMID 12136133.

- ↑ Rasmussen, A. F. Jr.; Stokes, J. C.; Smadel, J. E. (March 1948). "The Army Experience With Influenza, 1946–1947". American Journal of Epidemiology. 47 (2): 142–149. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a119191. PMID 18908909. Archived from the original on 2022-03-25. Retrieved 2022-10-04 – via Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Viboud, C.; Tam, T.; Fleming, D.; Miller, M. A.; Simonsen, L. (April 2006). "1951 Influenza Epidemic, England and Wales, Canada, and the United States". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (4): 661–668. doi:10.3201/eid1204.050695. PMC 3294686. PMID 16704816.

- 1 2 3 4 Smadel, J. E. (February 1958). "Influenza Vaccine". Public Health Reports. 73 (2): 129–132. doi:10.2307/4590060. JSTOR 4590060. PMC 1951635. PMID 13505997.

- 1 2 3 Furman, Bess (11 June 1957). "Vaccine Is Tested for Far East Flu". The New York Times. p. 37. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ↑ "State Acts to Bar Far East Influenza". The New York Times. 13 June 1957. p. 24. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ↑ "U.S. Acts to Combat Far East Influenza". The New York Times. 26 June 1957. p. 9. Archived from the original on 31 December 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ↑ "Influenza Vaccine". The New York Times. 7 July 1957. p. 119. Archived from the original on 3 February 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ↑ Tulchinsky, Theodore H. (2018). "Maurice Hilleman: Creator of Vaccines That Changed the World". Case Studies in Public Health: 443–470. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-804571-8.00003-2. ISBN 9780128045718. PMC 7150172.

- ↑ "CDC influenza report no. 2". CDC Influenza Reports. 12 July 1957. Archived from the original on 21 May 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022 – via CDC.

- 1 2 "6 Firms Develop Vaccine to Combat Asiatic Flu". The Evening Star. 3 July 1957. p. A3. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ↑ "Human Volunteers Test Vaccine for Asiatic Flu". The Evening Star. 9 July 1957. p. A1. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ↑ "Vaccine Standards for Asian Flu Set". The New York Times. 11 July 1957. p. 4. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ↑ Furman, Bess (2 August 1957). "U.S. Flu Outbreak Called Probable". The New York Times. p. 17. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ↑ Brooks, Charles G. (2 August 1957). "Sweeping Flu Outbreak Feared by Health Chief". The Evening Star. p. A9. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ↑ "Defense Against Asiatic Influenza". The New York Times. 4 August 1957. p. T9. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ↑ "Asiatic Flu Shots Start Next Month". The New York Times. 11 August 1957. p. 35. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ↑ "CDC influenza report no. 12". CDC Influenza Reports. 16 August 1957. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022 – via CDC.

- ↑ "D.C. Doctors Pressured For Asiatic Flu Vaccine". The Evening Star. 18 August 1957. p. A1. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ↑ "Flu Shots: Who & When". Time. 26 August 1957. p. 76. Archived from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ↑ "Athletes to Get Flu Shots". The New York Times. 18 August 1957. p. S5. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ↑ "U.S. Denies Flu Vaccine Will Boom Egg Prices". The Evening Star. 21 August 1957. p. A23. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Eisenhower Inoculated, Believed Exposed to Flu". The Evening Star. 26 August 1957. pp. A1, A6. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ↑ "Early Tests on Vaccine Are Called 'Promising'". The Evening Star. 22 August 1957. p. A26. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- 1 2 3 Lawrence, W. H. (27 August 1957). "Eisenhower Gets an Asian Flui Shot". The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ↑ "Health officers' meeting on Asian influenza". Public Health Reports. 72 (11): 998–1000. November 1957. PMC 2031400. PMID 13485293.

- ↑ "More Flu Vaccine Made Available". The New York Times. 29 August 1957. p. 29. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- 1 2 Fowle, F. (30 August 1957). "Public Flu Shots Due in September". The New York Times. p. 21. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- 1 2 "1st Flu Vaccine Not Seen Here Until October". The Evening Star. 30 August 1957. p. A23. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ↑ "Needles Public Health". The Evening Star. 30 August 1957. p. A18. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Doctors Here Receive Vaccine for Patients". The Evening Star. 31 August 1957. p. A1. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- 1 2 "Asiatic Flu Vaccine In Limited Supply Only". The Evening Star. 1 September 1957. p. A1. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ↑ Mattingly, T. E. (3 September 1957). "Flu Vaccine". The Evening Star. p. A12. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ↑ "Noxious Visitor". The Evening Star. 3 September 1957. p. A12. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ↑ "Mrs. Hobby Terms Free Vaccine Idea a Socialistic Step". The New York Times. 15 June 1955. p. 1. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ↑ "Confronting a Pandemic, 1957". The Scientist Magazine®. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- ↑ "Asian Influenza Pandemic | History of Vaccines". www.historyofvaccines.org. Archived from the original on 15 April 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- 1 2 "Pandemic flu virus from 1957 mistakenly sent to labs". CIDRAP. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ↑ Vynnycky, E; Edmunds, WJ (February 2008). "Analyses of the 1957 (Asian) influenza pandemic in the United Kingdom and the impact of school closures". Epidemiology and Infection. 136 (2): 166–179. doi:10.1017/S0950268807008369. ISSN 0950-2688. PMC 2870798. PMID 17445311.

- ↑ "Flu Toll Reaches 300 As Cases Rise – U.S. Says 1,000,000 Fell III Last Week--Death Rate Called 'Not Alarming'". The New York Times. 1957-10-25. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2021-06-25. Retrieved 2021-06-21.

- ↑ The influenza epidemic in England and Wales, 1957-1958. London: Stationery Office. 1960. p. 21.

- ↑ Sivaramakrishnan, Kavita (November 2020). "Endemic risks: influenza pandemics, public health, and making self-reliant Indian citizens". Journal of Global History. 15 (3): 459–477. doi:10.1017/S1740022820000340. ISSN 1740-0228. S2CID 228981283. Archived from the original on 2021-12-31. Retrieved 2022-10-04.

- ↑ "Symposium on the Asian Influenza Epidemic, 1957". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 51 (12): 1009–1018. 1958-12-01. doi:10.1177/003591575805101205. ISSN 0035-9157.

- ↑ Meltzer, Martin I.; Gambhir, Manoj; Atkins, Charisma Y.; Swerdlow, David L. (2015-05-01). "Standardizing Scenarios to Assess the Need to Respond to an Influenza Pandemic". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 60 (suppl_1): S1–S8. doi:10.1093/cid/civ088. ISSN 1537-6591. PMC 4481578. PMID 25878296. Archived from the original on 2022-10-17. Retrieved 2022-10-04.

- ↑ Mamelund*, Svenn-Erik; Iversen, Bjørn G. (2000-02-10). "Sykelighet og dødelighet ved pandemisk influensa i Norge". Tidsskrift for den Norske Legeforening (in norsk). ISSN 0029-2001. Archived from the original on 2021-08-19. Retrieved 2022-10-04.

- ↑ Taubenberger, Jeffery K.; Morens, David M. (January 2006). "1918 Influenza: the Mother of All Pandemics". Emerg Infect Dis. 12 (1): 15–22. doi:10.3201/eid1201.050979. PMC 3291398. PMID 16494711.

- ↑ Napoli, C.; Fabiani, M.; Rizzo, C.; Barral, M.; Oxford, J.; Cohen, J. M.; Niddam, L.; Goryński, P.; Pistol, A.; Lionis, C.; Briand, S. (2015-02-19). "Assessment of human influenza pandemic scenarios in Europe". Eurosurveillance. 20 (7): 29–38. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES2015.20.7.21038. ISSN 1560-7917. PMID 25719965. Archived from the original on 2022-11-03. Retrieved 2022-10-04.

- ↑ Viboud, Cécile; Simonsen, Lone (2013-07-13). "Timely estimates of influenza A H7N9 infection severity". The Lancet. 382 (9887): 106–108. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61447-6. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7136974. PMID 23803486.

- 1 2 "Preparing for the next human influenza pandemic: Celebrating 10 years of the Pandemic Influenza Preparedness Framework". World Health Organization. 23 May 2021. Archived from the original on 2021-05-22. Retrieved 2022-01-03.

- ↑ "Influenza: are we ready?". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 2022-01-03. Retrieved 2022-01-03.

- ↑ Simonsen, Lone; Viboud, Cecile (2021-08-12). "A comprehensive look at the COVID-19 pandemic death toll". eLife. 10: e71974. doi:10.7554/eLife.71974. ISSN 2050-084X. PMC 8360646. PMID 34382937. Archived from the original on 2022-12-30. Retrieved 2022-10-04.

- ↑ "1957 Flu Pandemic | Pandemic Influenza Storybook | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 18 September 2018. Archived from the original on 23 August 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ↑ Fox, Justin (2021). "Solving the Mystery of the 1957 and 1968 Flu Pandemics". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 2021-03-11.

- ↑ Simonsen, Lone; Clarke, Matthew J.; Schonberger, Lawrence B.; Arden, Nancy H.; Cox, Nancy J.; Fukuda, Keiji (1998-07-01). "Pandemic versus Epidemic Influenza Mortality: A Pattern of Changing Age Distribution". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 178 (1): 53–60. doi:10.1086/515616. ISSN 0022-1899. PMID 9652423. Archived from the original on 2022-12-30. Retrieved 2022-10-04.

- ↑ Glezen, W. Paul (1996-01-01). "Emerging Infections: Pandemic Influenza". Epidemiologic Reviews. 18 (1): 64–76. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017917. ISSN 0193-936X. PMID 8877331. Archived from the original on 2022-12-30. Retrieved 2022-10-04.

- ↑ "Coronavirus: action plan. A guide to what you can expect across the UK" (PDF). gov.uk. 3 March 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- 1 2 Pinsker, Joe (28 February 2020). "How to Think About the Plummeting Stock Market". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 4 April 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

Perhaps a better parallel is the flu pandemic of 1957 and ’58, which originated in East Asia and killed at least 1 million people, including an estimated 116,000 in the U.S. In the second half of 1957, the Dow fell about 15 percent. "Other things happened over that time period" too, Wald notes, but "at least there was no world war."

- ↑ Kutzner, Maximilian (19 May 2020). "Debatte zur Herkunft der Asiatischen Grippe 1957" [Debate on the origin of the Asian flu of 1957]. Deutschland Archiv (in Deutsch). Federal Agency for Civic Education. Archived from the original on 17 January 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ↑ Mullally, Una. "An 'Asian flu' pandemic closed 17 Dublin schools in 1957". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

Further reading

- Chowell, Gerardo; Simonsen, Lone; Fuentes, Rodrigo; Flores, Jose; Miller, Mark A.; Viboud, Cécile (May 2017). "Severe mortality impact of the 1957 influenza pandemic in Chile". Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. 11 (3): 230–239. doi:10.1111/irv.12439. PMC 5410718. PMID 27883281.

- Cobos, April J.; Nelson, Clinton G.; Jehn, Megan; Viboud, Cécile; Chowell, Gerardo (2016). "Mortality and transmissibility patterns of the 1957 influenza pandemic in Maricopa County, Arizona". BMC Infectious Diseases. 16 (1): 405. doi:10.1186/s12879-016-1716-7. ISSN 1471-2334. PMC 4982429. PMID 27516082.