Australian bat lyssavirus

| Australian bat lyssavirus | |

|---|---|

| |

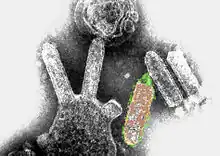

| Colored transmission electron micrograph of Australian bat lyssavirus. The bullet-like objects are the virions, and some of them are budding off from a cell. | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Negarnaviricota |

| Class: | Monjiviricetes |

| Order: | Mononegavirales |

| Family: | Rhabdoviridae |

| Genus: | Lyssavirus |

| Species: | Australian bat lyssavirus |

Australian bat lyssavirus (ABLV), originally named Pteropid lyssavirus (PLV), is a zoonotic virus closely related to the rabies virus. It was first identified in a 5-month-old juvenile black flying fox (Pteropus alecto) collected near Ballina in northern New South Wales, Australia, in January 1995 during a national surveillance program for the recently identified Hendra virus.[1] ABLV is the seventh member of the genus Lyssavirus (which includes Rabies virus) and the only Lyssavirus member present in Australia.

Prevalence

ABLV is distributed throughout Australia in a variety of bat species which are believed to be the primary reservoir for the virus.

Surveillance initiatives also confirmed the presence of lyssavirus in both Pteropid (Gould et al.., 1998) and insectivorous bats (Gould et al.., 2002; Hooper et al.., 1997), and later, human infections were reported following encounters with both fruit and insectivorous bats (Allworth et al.., 1996; Hanna et al.., 2000; Warrilow, 2005; Warrilow et al.., 2002). Indeed, ABLV has now been isolated from five different bat species, all four species of Pteropodidae in Australia and from an insectivorous bat species, the yellow-bellied sheath-tailed bat (Saccolaimus flaviventris), with two distinct lineages apparently circulating in insectivorous and frugivorous bats (Fraser et al.., 1996; Gould et al.., 1998, 2002; Guyatt et al.., 2003). Phylogenetically and serologically, ABLV isolates appear to be more closely related to RABV than any of the other Old World lyssaviruses (Fig. 2). Although the black flying fox is a native fruit bat to Australia and is present on islands to the north, ABLV has only been isolated in Australia. However, serosurveillance of bat populations in the Philippines has suggested that lyssavirus infection of bats might be more widespread than previously thought (Arguin et al.., 2002).[2]

Bat lyssavirus and human infection

Three cases of ABLV in humans have been confirmed, all of them fatal. The first occurred in November 1996, when an animal caregiver was scratched by a yellow-bellied sheath-tailed bat. Onset of a rabies-like illness occurred 4–5 weeks following the incident, with death 20 days later. ABLV was identified from brain tissue by polymerase chain reaction and immunohistochemistry.

In August 1996, a middle-aged woman in Queensland was bitten on the finger by a flying fox while attempting to remove it from a child on whom it had landed. Six months later, following heightened public attention from the first ABLV death, she consulted a GP regarding testing for the virus. Postexposure treatment was advised, but for an unknown reason did not occur. After a 27-month incubation, a rabies-like illness developed. The condition worsened after hospital admission, and she died 19 days after the onset of illness. On the day the woman was hospitalized, cerebrospinal fluid, serum, and saliva were submitted for testing.[4] On the fourth day of her hospital admission, these tests were returned with results of probable ABLV infection. Postmortem tests were all strongly positive for ABLV. The length of incubation is unusual as classical rabies has typical incubation periods of less than 90 days.

In December 2012, an eight-year-old boy was scratched by a bat in north Queensland. He became ill two months later and died on 22 February 2013.[5]

Rabies vaccine and immunoglobulin are effective in prophylactic and therapeutic protection from ABLV infection. Since the emergence of the virus, rabies vaccine is administered to individuals with a heightened risk of exposure, and vaccine and immunoglobulin are provided for postexposure treatment.

ABLV is one of four zoonotic viruses discovered in pteropid bats since 1994, the others being Hendra virus, Nipah virus, and Menangle virus. Of these, ABLV is the only virus known to be transmissible to humans directly from bats without an intermediate host.

Dr John Carnie [Victoria's Chief Health Officer] said Australian bat lyssavirus was a rare but fatal disease that could be transmitted to humans or pets bitten or scratched by bats. But he said only two cases have ever been recorded, both in Queensland. No animal or person in Victoria has ever contracted the disease, Dr Carnie said. Nine Victorian flying foxes have been found with the virus since 1996. "Under no circumstances should people handle flying foxes on their property as some diseases they carry, such as Australian bat lyssavirus, are transmissible to humans," Dr Carnie said in a statement. Only trained volunteers or workers should handle bats. Anyone who encounters a sick or injured flying fox should not try to catch it but call the DSE Customer Service Centre on 136 186.[6]

ABLV was detected in a bat found in the Melbourne suburb of Kew in July 2011. The discovery prompted health authorities to issue warnings to Melbourne residents not to touch the creatures.[7]

ABLV was confirmed in two horses on Queensland's Darling Downs in May 2013. Both horses were euthanased when their condition deteriorated despite treatment and the attending veterinarian performed a post mortem examination obtaining samples that allowed for the laboratory diagnosis. The property was then quarantined. Three dogs and the four horses in closest contact received postexposure prophylaxis, as did all nine in-contact people. The virus was isolated and identified as the insectivorous bat strain. These cases have prompted reconsideration of the potential spillover of ABLV into domestic animal species. Veterinarians are urged to consider ABLV as a differential diagnosis in cases of progressive generalized neurological disease.

ABLV was found in one flying fox in 2019 and three in 2020.[8]

See also

References

- ↑ Speare 1997, p. 117

- ↑ Banyard 2011, p. 251

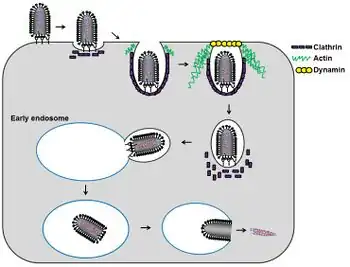

- ↑ Weir, Dawn L.; Annand, Edward J.; Reid, Peter A.; Broder, Christopher C. (19 February 2014). "Recent observations on Australian bat lyssavirus tropism and viral entry". Viruses. 6 (2): 909–926. doi:10.3390/v6020909. ISSN 1999-4915.

- ↑ Hanna, J. N.; Carney, I. K.; Smith, G. A.; Tannenberg, A. E.; Deverill, J. E.; Botha, J. A.; Serafin, I. L.; Harrower, B. J.; Fitzpatrick, P. F.; Searle, J. W. (2000). "Australian Bat Lyssavirus Infection: A Second Human Case, with a Long Incubation Period". The Medical Journal of Australia. 172 (12): 597–599. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2000.tb124126.x. PMID 10914106. S2CID 32907529. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 26 July 2008.

- ↑ "Child dies of bat virus in Brisbane hospital". Adelaidenow. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ "Don't handle bats, Vic health chief warns". The Sydney Morning Herald. 25 May 2011. Archived from the original on 28 May 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2011.

- ↑ Devine, Miranda (17 July 2011). "It's batty not to cleanse this scourge". Herald Sun. Archived from the original on 30 December 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ↑ Mounter, Brendan (7 December 2020). "Lyssavirus infection confirmed in Far North Queensland as bat-related injuries rise". ABC (Australian Broadcasting Corporation). Archived from the original on 8 December 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- Samaratunga, H.; Searle, J. W.; Hudson, N. (1998). "Non-rabies Lyssavirus Human Encephalitis from Fruit Bats: Australian Bat Lyssavirus (Pteropid Lyssavirus) Infection". Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology. 24 (4): 331–335. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2990.1998.00129.x. PMID 9775399. S2CID 22171516.

- Fraser, G. C.; Hooper, P. T.; Lunt, R. A.; Gould, A. R.; Gleeson, L. J.; Hyatt, A. D.; Russell, G. M.; Kattenbelt, J. A. (1996). "Encephalitis Caused by a Lyssavirus in Fruit Bats in Australia". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2 (4): 327–331. doi:10.3201/eid0204.960408. PMC 2639915. PMID 8969249.

- Speare, R.; Skerratt, L.; Foster, R.; Berger, L.; Hooper, P.; Lunt, R.; Blair, D.; Hansman, D.; Goulet, M.; Cooper, S. (1997). "Australian Bat Lyssavirus Infection in three Fruit Bats from north Queensland" (PDF). Communicable Disease Intelligence. 21 (9): 117–120. PMID 9145563. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- Banyard; et al. (2011). "Chapter 12: Bats and Lyssaviruses". In Jackson, A. C. (ed.). Research Advances in Rabies. Advances in Virus Research. Vol. 79. Elsevier. pp. 239–289. ISBN 978-0-12-387040-7.

- Annand, E.J.; Reid, P.A. (2014). "Clinical review of two fatal equine cases of infection with the insectivorous bat strain of Australian bat lyssavirus". Australian Veterinary Journal. 92 (9): 324–332. doi:10.1111/avj.12227. PMID 25156050.

External links

- "Australian Bat Lyssavirus". Queensland Health. Archived from the original on 20 April 2013.