Omsk hemorrhagic fever

| Omsk hemorrhagic fever | |

|---|---|

| |

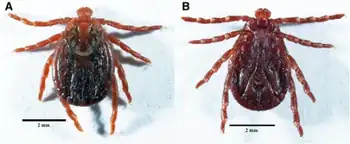

| Dermacentor reticulatus a} dorsal view b) ventral view of tick (trasmits Omsk hemorrhagic virus[1]) | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

Omsk hemorrhagic fever is a viral hemorrhagic fever caused by a Flavivirus.[2]

It was found in Siberia[3] and was named for an outbreak in the city of Omsk. First records of the new virus appeared around 1940-1943.

Signs and symptoms

There are a number of symptoms of the virus. In the first 1–8 days the first phase begins. The symptoms in this phase are:

- chills

- headache

- pain in the lower and upper extremities and severe prostration

- a rash on the soft palate

- swollen glands in the neck

- appearance of blood in the eyes (conjunctival suffusion)

- dehydration

- hypotension

- gastrointestinal symptoms (symptoms relating to the stomach and intestines)

- patients may also experience effects on the central nervous system

In 1–2 weeks, some people may recover, although others might not. They might experience a focal hemorrhage in mucosa of gingival, uterus, and lungs, a papulovesicular rash on the soft palate, cervical lymphadenopathy (it occurs in the neck which that enlarges the lymph glandular tissue), and occasional neurological involvement. If the patient still has OHF after 3 weeks, then a second wave of symptoms will occur. It also includes signs of encephalitis. In most cases if the sickness does not fade away after this period, the patient will die. Patients that recover from OHF may experience hearing loss, hair loss, and behavioral or psychological difficulties associated with neurological conditions.

Cause

| Omsk hemorrhagic fever virus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Flavivirus structure and genome | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Kitrinoviricota |

| Class: | Flasuviricetes |

| Order: | Amarillovirales |

| Family: | Flaviviridae |

| Genus: | Flavivirus |

| Species: | Omsk hemorrhagic fever virus |

| Synonyms[4] | |

|

Omsk haemorrhagic fever virus | |

Omsk hemorrhagic fever is caused by Omsk hemorrhagic fever virus (OHFV), a member of the Flavivirus family. The virus was discovered by Mikhail Chumakov and his colleagues between 1945 and 1947 in Omsk, Russia. The infection is found in Western Siberia, in places including Omsk Oblast, Novosibirsk Oblast, Kurgan Oblast, Tyumen Oblast. The virus survives in water and is transferred to humans via contaminated water or an infected tick.

Spread

The main hosts of OHFV are rodents like the non-native muskrat. OHFV originates in ticks, who then transmit it to rodents by biting them. Humans become infected through tick bites or contact with a muskrat. Humans can also become infected through contact with blood, feces or urine of a dead or sick muskrat (or any type of rat). The virus can also spread through milk from infected goats or sheep. There is no evidence that the virus is contagious among humans.

Evolution

The virus appears to have evolved within the last 1000 years.[5] The viral genomes can be divided into 2 clades—A and B. Clade A has five genotypes and clade B has one. These clades separated about 700 years ago. This separation appears to have occurred in the Kurgan province. Clade A subsequently underwent division into clade C, D and E 230 years ago. Clade C and E appear to have originated in the Novosibirsk and Omsk Provinces respectively. The muskrat Ondatra zibethicus which is highly susceptible to this virus was introduced into this area in the 1930s.

Diagnosis

Omsk Hemorrhagic Fever could be diagnosed by isolating virus from blood, or by serologic testing using immunosorbent serological assay. OHF rating of fatality is 0.5–3%. There is no specific treatment for OHF so far but one way to help get rid of OHF is by supportive therapy. Supportive therapy helps maintain hydration and helps to provide precautions for patients with bleeding disorders.

Prevention

Preventing Omsk Hemorrhagic Fever consists primarily in avoiding being exposed to tick. Persons engaged in camping, farming, forestry, hunting (especially the Siberian muskrat) are at greater risk and should wear protective clothing or use insect repellent for protection. The same is generally recommended for persons at sheltered locations.

Management

There is currently no treatment for this infection, however hydration is important.[6]

References

- ↑ Földvári, Gábor; Široký, Pavel; Szekeres, Sándor; Majoros, Gábor; Sprong, Hein (1 June 2016). "Dermacentor reticulatus: a vector on the rise". Parasites & Vectors. 9: 314. doi:10.1186/s13071-016-1599-x. ISSN 1756-3305. Archived from the original on 1 February 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ↑ Holbrook MR, Aronson JF, Campbell GA, Jones S, Feldmann H, Barrett AD (January 2005). "An animal model for the tickborne flavivirus--Omsk hemorrhagic fever virus". J. Infect. Dis. 191 (1): 100–8. doi:10.1086/426397. PMID 15593010.

- ↑ Lin D, Li L, Dick D, et al. (August 2003). "Analysis of the complete genome of the tick-borne flavivirus Omsk hemorrhagic fever virus". Virology. 313 (1): 81–90. doi:10.1016/S0042-6822(03)00246-0. PMID 12951023.

- ↑ ICTV 2nd Report Fenner, F. (1976). Classification and nomenclature of viruses. Second report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Intervirology 7: 1-115. https://talk.ictvonline.org/ictv/proposals/ICTV%202nd%20Report.pdf Archived 2021-11-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Karan LS, Ciccozzi M, Yakimenko VV, Presti AL, Cella E, Zehender G, Rezza G, Platonov AE (2013). "The deduced evolution history of Omsk hemorrhagic fever virus". J Med Virol. 86 (7): 1181–7. doi:10.1002/jmv.23856. PMID 24259273. S2CID 36929638.

- ↑ "Treatment | Omsk Hemorrhagic Fever | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 21 February 2019. Archived from the original on 25 September 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

External links

- "Omsk hemorrhagic fever (OHF)". Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers (VHFs). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 9 December 2013. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|