Human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis

| Human monocytic ehrlichiosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Human Ehrlichial Infection, Human Monocytic Type | |

| |

| Ehrlichia chaffeensis | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever, headache, malaise, and muscle aches |

| Causes | Ehrlichia chaffeensis |

| Diagnostic method | PCR |

| Differential diagnosis | Human Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis,Sennetsu Fever, Lyme disease |

| Prevention | Insect repellent |

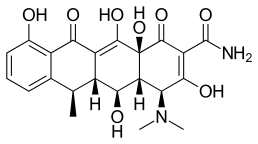

| Treatment | Tetracycline antibiotics, Doxycycline |

Human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis is a form of ehrlichiosis associated with Ehrlichia chaffeensis.[1][2] This bacterium is an obligate intracellular pathogen affecting monocytes and macrophages.[3]

Human monocytic ehrlichiosis caused by E. chaffeensis is known to spread through tick infection primarily in the Southern, South-central and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States.[4] In recent years, the lone star tick has expanded its range along the East Coast to New England, putting more humans at risk for tick-borne infections.[5]

Signs and symptoms

The most common symptoms are fever, headache, malaise, and muscle aches (myalgia). Compared to human granulocytic anaplasmosis, rash is more common.[6] Laboratory abnormalities include thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and elevated liver tests.[7]

The severity of the illness can range from minor or asymptomatic to life-threatening. CNS involvement may occur. A serious septic or toxic shock-like picture can also develop, especially in patients with impaired immunity.[8]

Cause

HME is caused by Ehrlichia chaffeensis, and is transmitted via tick vector(s) (Amblyomma americanum).[7]

Mechanism

E. chaffeensis causes human monocytic ehrlichiosis and is known to infect monocytes.[3] It has also been known to infect other cell types such as lymphocytes, atypical lymphocytes, myelocytes, and neutrophils, but monocytes appear to best harbor the infection.[3]

E. chaffeensis can be transmitted to uninfected tick larvae when feeding on the blood from an infected host.[9] The infection is then maintained and can be transmitted to a reservoir organism or humans at the nymphal stage. Adult ticks can maintain the infection or be infected from feeding on the blood of an infected reservoir organism and may also pass E. chaffeensis to humans or other uninfected reservoir organisms.[3] Transovarial transmission is not known to occur, so eggs and unfed larvae are not believed to be infected.[9]

E. chaffeensis has also been shown to infect canines both naturally and artificially, symptoms in canine infections are hard to differentiate between E. chaffeensis infection and other Ehrlichia species.[10][11]

Diagnosis

Tick exposure is often overlooked, for individuals living in high-prevalence areas who spend time outdoors, a high degree of clinical suspicion should be employed.[7][12]

Ehrlichia serologies can be negative in the acute period. Polymerase chain reaction is therefore the laboratory diagnostic tool of choice.[13][7]

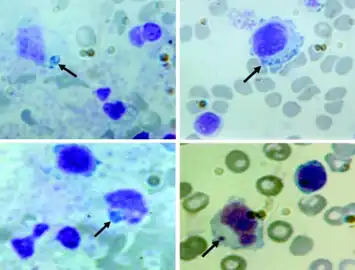

Peripheral blood smears shows variable-sized basophilic inclusions in mononuclear cells from child with human monocytic ehrlichiosis

Peripheral blood smears shows variable-sized basophilic inclusions in mononuclear cells from child with human monocytic ehrlichiosis.png.webp) Liver biopsy sample with (fatal) human monocytic ehrlichiosis

Liver biopsy sample with (fatal) human monocytic ehrlichiosis.png.webp) Image of liver biopsy sample from individual with (fatal) human monocytic ehrlichiosis

Image of liver biopsy sample from individual with (fatal) human monocytic ehrlichiosis

Treatment

If ehrlichiosis is suspected, treatment should not be delayed while waiting for a definitive laboratory confirmation, as prompt doxycycline therapy has been associated with improved outcomes.[14] Tetracycline antibiotics or doxycycline are the treatments of choice.[7]

Presentation during early pregnancy can complicate treatment.[15] Rifampin has been used in pregnancy and in patients allergic to doxycycline.[16]

Epidemiology

In the US, human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis occurs across the south-central, southeastern, and mid-Atlantic states, regions where both the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and Lone Star ticks (Amblyomma americanum) thrive.[17][18]

Human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis occurs in California in Ixodes pacificus ticks and in Dermacentor variabilis ticks.[19] Nearly 600 cases were reported to the CDC in 2006. In 2001–2002, the incidence was highest in Missouri, Tennessee, and Oklahoma, as well as in people older than 60.[20]

Reasearch

In terms of investigation of the bacterium, E. chaffeensis, we find it might be responsive to antibacterial drug rifampin, though obviously more research is needed to determine safety.[7][21]

Currently, Rifampin is an antibiotic whose main purpose is prevention or treament of tuberculosis (TB).[22]

See also

References

- ↑ Schutze GE, Buckingham SC, Marshall GS, et al. (June 2007). "Human monocytic ehrlichiosis in children". Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 26 (6): 475–9. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e318042b66c. PMID 17529862. S2CID 1191660.

- ↑ Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology. Mosby. pp. 1130. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- 1 2 3 4 Ganguly, S; Mukhopadhayay, S (2008). "Tick-borne ehrlichiosis infection in human beings" (PDF). J Vector Bourne. 45 (4): 273–280. PMID 19248653. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 August 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ↑ Barker, R. W. (2000). "Naturally occurring ehrlichia chaffeensis infection in coyotes from oklahoma". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 6 (5): 477–80. doi:10.3201/eid0605.000505. PMC 2627953. PMID 10998377.

- ↑ Little, S. E. (2007, January). New developments in managing vector-borne diseases. Retrieved from http://www.iknowledgenow.com/tocnavc2007smallanimal.cfm Archived 2012-01-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Dumler JS, Choi KS, Garcia-Garcia JC, et al. (December 2005). "Human granulocytic anaplasmosis and Anaplasma phagocytophilum". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (12): 1828–34. doi:10.3201/eid1112.050898. PMC 3367650. PMID 16485466.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Human Monocytic Ehrlichiosis (HME)". NORD. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ↑ Paddock CD, Folk SM, Shore GM, et al. (November 2001). "Infections with Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Ehrlichia ewingii in persons coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 33 (9): 1586–94. doi:10.1086/323981. PMID 11568857. Archived from the original on 2022-05-11. Retrieved 2022-01-09.

- 1 2 Long, S. W. (2003). "Evaluation of transovarial transmission and transmissibility of Ehrlichia chaffeensis (Rickettsiales: Anaplasmataceae) in Amblyomma americanum (Acari: Ixodidae)". Journal of Medical Entomology. 40 (6): 1000–1004. doi:10.1603/0022-2585-40.6.1000. PMID 14765684. S2CID 21437783.

- ↑ Baneth, G. (2010). Ehrlichia and anaplasma infections. Paper presented at World small animal veterinary congress. Retrieved from http://www.ivis.org/proceedings/wsava/2010/d12.pdf Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Shaw, Susan E.; Day, Michael J.; Birtles, Richard J.; Breitschwerdt, Edward B. (1 February 2001). "Tick-borne infectious diseases of dogs". Trends in Parasitology. 17 (2): 74–80. doi:10.1016/S1471-4922(00)01856-0. ISSN 1471-4922. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ↑ "Transmission of the bacteria which cause ehrlichiosis | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 17 January 2019. Archived from the original on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ↑ Prince LK, Shah AA, Martinez LJ, Moran KA (August 2007). "Ehrlichiosis: making the diagnosis in the acute setting". Southern Medical Journal. 100 (8): 825–8. doi:10.1097/smj.0b013e31804aa1ad. PMID 17713310. S2CID 31487400.

- ↑ Hamburg BJ, Storch GA, Micek ST, Kollef MH (March 2008). "The importance of early treatment with doxycycline in human ehrlichiosis". Medicine. 87 (2): 53–60. doi:10.1097/MD.0b013e318168da1d. PMID 18344803. S2CID 2632346.

- ↑ Muffly T, McCormick TC, Cook C, Wall J (2008). "Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis complicating early pregnancy". Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2008: 1–3. doi:10.1155/2008/359172. PMC 2396214. PMID 18509484.

- ↑ Krause PJ, Corrow CL, Bakken JS (September 2003). "Successful treatment of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in children using rifampin". Pediatrics. 112 (3 Pt 1): e252–3. doi:10.1542/peds.112.3.e252. PMID 12949322. Archived from the original on 2019-12-10. Retrieved 2022-01-09.

- ↑ Andrews, K. E.; Eversman, K. K.; Foré, S. A.; Kim, H. J. (2019). "Seasonality and trends in incidence of human ehrlichiosis in two Missouri ecoregions". Epidemiology and Infection. 147: e123. doi:10.1017/S0950268818003448. Archived from the original on 27 October 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ↑ Rose, Stuart R.; Keystone, Jay S.; Connor, Bradley A.; Hackett, Peter; Kozarsky, Phyllis E.; Quarry, Doug (1 January 2006). "CHAPTER 9 - Insect-Borne Diseases". International Travel Health Guide 2006-2007 (Thirteenth Edition). Mosby. pp. 140–158. ISBN 978-0-323-04050-1. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ↑ Holden K, Boothby JT, Anand S, Massung RF (July 2003). "Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi, Ehrlichia chaffeensis, and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) from a coastal region of California". J. Med. Entomol. 40 (4): 534–9. doi:10.1603/0022-2585-40.4.534. PMID 14680123.

- ↑ "Statistics and Epidemiology: Annual Cases of Ehrlichiosis in the United States". Ehrlichiosis. Division of Vector-Borne Diseases (DVBD), National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (NCEZID), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 5 September 2013. Archived from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ↑ Abusaada, Khalid; Ajmal, Saira; Hughes, Laura (1 January 2016). "Successful Treatment of Human Monocytic Ehrlichiosis with Rifampin". Cureus. 8 (1): e444. doi:10.7759/cureus.444. ISSN 2168-8184. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ↑ "Rifampin Uses, Side Effects & Warnings". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 21 September 2022. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |