Mokola lyssavirus

| Mokola lyssavirus | |

|---|---|

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Negarnaviricota |

| Class: | Monjiviricetes |

| Order: | Mononegavirales |

| Family: | Rhabdoviridae |

| Genus: | Lyssavirus |

| Species: | Mokola lyssavirus |

| Synonyms | |

|

Mokola virus | |

Mokola lyssavirus, commonly called Mokola virus (MOKV), is an RNA virus related to rabies virus that has been sporadically isolated from mammals across sub-Saharan Africa. The majority of isolates have come from domestic cats exhibiting symptoms characteristically associated to rabies virus infection.[1]

As of 2021, there have been two confirmed cases of Mokola virus infection in humans, of which one was fatal.[2][3] The rabies vaccine does not confer cross-protective immunity to Mokola virus, and no other known treatment for MOKV exists.

Classification

Mokola virus (MOKV) is a member of the genus Lyssavirus, which belongs to the family Rhabdoviridae. MOKV is one of four lyssaviruses found in Africa. The other three viruses are the classic rabies virus, Duvenhage virus and Lagos bat virus.[1]

Emergence

.jpg.webp)

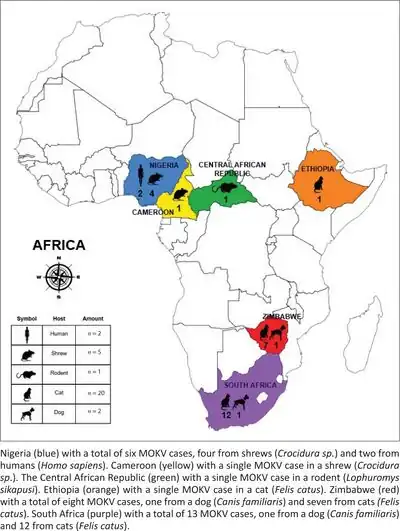

MOKV was first isolated in Nigeria, in 1968, from three shrews (Crocidura species) found in the Mokola forest, Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria. The virus was shown to be morphologically and serologically related to rabies virus. Since the initial isolation of MOKV, the virus has been mainly isolated in domestic cats and small mammals in sub-Saharan Africa.[4]

There have been two recorded cases of human infection with MOKV, with both instances occurring in Nigeria. Both cases involved young Nigerian females. The first patient, who had been suffering from a fever and convulsions, recovered fully from infection.[2] The second case, which occurred in 1972, involved a 6-year-old girl who had been suffering from drowsiness. The second patient ultimately suffered from paralysis and a terminal coma as a result of the MOKV infection.[3]

The origin of the MOKV in both human cases of MOKV infection remains unidentified.[1]

Genome and structure

The MOKV genome consists of a non-segmented, single-stranded, negative-sense RNA molecule of 11,939 nucleotides in length. It is estimated that 90.3% of the MOKV genome consists of protein-encoding or signal-encoding sequences.[5]

The genome encodes five proteins: matrix protein M; transmembrane glycoprotein G; nucleoprotein N; phosphoprotein P; and the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase L.[5]

MOKV is an enveloped virus, with the envelope lined with spikes consisting of the viral protein G.[4] MOKV exhibits the 'bullet-shaped' morphology that is characteristic of members of the Rhabdoviridae family.[4]

Evolution

This virus appears to have evolved between 279 and 2,034 years before the present.[6]

Transmission

The human cases of human MOKV infection have demonstrated the zoonotic potential of MOKV,[2][3] but as a natural reservoir has not yet been identified, transmission of MOKV is poorly understood.

Considering the MOKV isolates from small mammals and domestic cats; it has been suggested that small mammals, which are preyed upon by domestic cats, may be the natural MOKV reservoir.[7]

Unlike other lyssaviruses, MOKV is able to replicate inside mosquito cells in vitro, suggesting that insects may be implicated in MOKV transmission.[8]

Pathology

Symptoms provoked by MOKV infection are similar to the symptoms associated with rabies virus infection, such as fever and headache. Ultimately, both MOKV and rabies virus infection can lead to death by encephalitis. The similarity between the symptoms associated with MOKV and rabies virus may be the reason why there are so few case records of MOKV infection, as MOKV infection might be falsely diagnosed as rabies virus infection.

There is one significant difference between the symptoms observed in domestic cats infected with MOKV and those with rabies virus. MOKV-infected domestic cats do not demonstrate the unprovoked aggressive behaviour typically associated with rabies virus-infected mammals.

Treatment and prevention

At present, there is no medical or veterinary vaccine that protects against MOKV infection.[1] It has long been established that, in spite of the relatedness between MOKV and rabies virus, immunisation with the rabies vaccine does not confer protection from MOKV infection. Isolation of MOKV from a number of domestic cats vaccinated with the rabies vaccine has demonstrated this.[4]

In order to neutralize rabies virus, the rabies vaccine targets the transmembrane glycoprotein G on the viral envelope. Variation in the amino acid sequences of the antigenic domain III within protein G between rabies virus and MOKV has rendered the rabies vaccine ineffective against MOKV infection.[4]

References

- 1 2 3 4 von Teichman BF, de Koker WC, Bosch SJ, Bishop GC, Meredith CD, Bingham J (December 1998). "Mokola virus infection: description of recent South African cases and a review of the virus epidemiology: case report". Journal of the South African Veterinary Association. 69 (4): 169–171. doi:10.4102/jsava.v69i4.847. PMID 10192092. Archived from the original on 31 March 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- 1 2 3 Familusi, J. B.; Moore, D. L. (January 1972). "Isolation of a Rabies Related Virus from the Cerebrospinal Fluid of a Child with 'Aseptic Meningitis'". African Journal of Medical Sciences. 3 (1): 93–96. PMID 5061272.

- 1 2 3 Familusi, J. B.; Osunkoya, B. O.; Moore, D. L.; Kemp, G. E.; Fabiyi, A. (November 1972). "A Fatal Human Infection with Mokola Virus". American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 21 (6): 959–963. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1972.21.959. PMID 4635777.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Nel, L. H. "Mokola Virus: A Brief Review of the Status Quo" (PDF). Sixth SEARG meeting, Lilongwe 18–21 June 2001. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- 1 2 Le Mercier, P.; Jacob, Y.; Tordo, N. (1997). "The complete Mokola virus genome sequence: structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase". Journal of General Virology. 78 (7): 1571–6. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-78-7-1571. PMID 9225031.

- ↑ Kgaladi, J; Wright, N; Coertse, J; Markotter, W; Marston, D; Fooks, AR; Freuling, CM; Müller, TF; Sabeta, CT; Nel, LH (2013). "Diversity and epidemiology of mokola virus". PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 7 (10): e2511. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002511. PMC 3812115. PMID 24205423.

- ↑ Sabeta, C.T.; Markotter, W.; Mohale, D.K.; Shumba, W.; Wandeler, A.I.; Nel, L.H. (September 2007). "Mokola virus in domestic mammals, South Africa". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 13 (9): 1371–3. doi:10.3201/eid1309.070466. PMC 2857310. PMID 18252112. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ↑ Aitken, T. H.; Kowalski, R. W.; Beaty, B. J.; Buckley, S. M.; Wright, J. D.; Shope, R. E.; Miller, B. R. (September 1984). "Arthropod Studies with Rabies-Related Mokola Virus". American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 33 (5): 945–952. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1984.33.945. PMID 6385743.