Desmoplastic small-round-cell tumor

| Desmoplastic small-round-cell tumor | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Intra-abdominal desmoplastic round cell tumour[1] | |

| |

| Desmoplastic small-round-cell tumor | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

| Symptoms | Pain, abdominal distention, mass, acute abdomen, ascites, organ obstruction[1] |

| Usual onset | Children, young adults (20s)[2] |

| Causes | Unknown[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Medical imaging; ultrasound, CT, MRI, PET[2] |

| Prognosis | Poor, 5-year survival ~%10-15%[1] |

| Frequency | Rare, males>females[1] |

Desmoplastic small-round-cell tumor (DSRCT) is a type of soft tissue sarcoma, a cancerous soft tissue tumor that typically occurs as masses in the abdomen.[1] There are typically no symptoms until the tumor becomes large enough to cause pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation or diarrhoea, and a swelling in the abdomen.[2] It may cause an acute abdomen, ascites, or organ obstruction.[1] It rarely occurs outside the abdomen.[1]

Diagnosis is by medical imaging; ultrasound, CT, MRI, and PET.[2] Confirmation is by biopsy.[2]

It most often occurs in children and adults in their 20s.[1] Males are affected significantly more than females, it whom it may be mistaken for ovarian cancer.[1]

Signs and symptoms

There are few early warning signs that a person has a DSRCT. They are often young and healthy as the tumors grow and spread uninhibited within the abdominal cavity. These are rare tumors and symptoms are often misdiagnosed by physicians. The abdominal masses can grow to enormous size before being noticed by the patient. The tumors can be felt as hard, round masses by palpating the abdomen.

First symptoms of the disease often include abdominal distention, abdominal mass, abdominal or back pain, gastrointestinal obstruction, lack of appetite, ascites, anemia, and cachexia.[3]

Other areas affected may include the lymph nodes, the lining of the abdomen, diaphragm, spleen, liver, chest wall, skull, spinal cord, large intestine, small intestine, bladder, brain, lungs, testicles, ovaries, and the pelvis. Reported sites of metastatic spread include the liver, lungs, lymph nodes, brain, skull, and bones. It is characterized by the EWS-WT1 fusion protein.

Genetics

There are no known risk factors that have been identified specific to the disease. The tumor appears to arise from the primitive cells of childhood, and is considered a childhood cancer.

Research has indicated that there is a chimeric relationship between DSRCT and Wilms' tumor and Ewing sarcoma. Together with neuroblastoma and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, they form the small-cell tumors.

DSRCT is associated with a unique chromosomal translocation t(11;22)(p13:q12)[4] resulting in an EWS-WT1 fusion transcript[5] that is diagnostic of this tumor.[6] This transcript codes for a protein that includes the N-terminal transactivation domain of EWSR1 and the DNA-binding domain of WT1.

The EWS/WT1 translocation product targets ENT4.[7] ENT4 is also known as PMAT.

Pathology

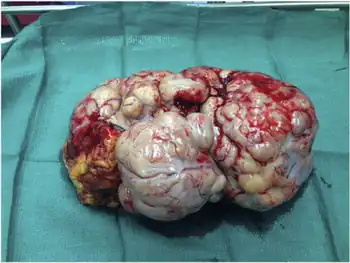

The entity was first described by pathologists William L. Gerald and Juan Rosai in 1989.[8] Pathology reveals well circumscribed solid tumor nodules within a dense desmoplastic stroma. Often areas of central necrosis are present. Tumor cells have hyperchromatic nuclei with increased nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio.

On immunohistochemistry, these cells have trilinear coexpression including the epithelial marker cytokeratin, the mesenchymal markers desmin and vimentin, and the neuronal marker neuron-specific enolase. Thus, although initially thought to be of mesothelial origin due to sites of presentation, it is now hypothesized to arise from a progenitor cell with multiphenotypic differentiation.

Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis

Because this is a rare tumor, not many family physicians or oncologists are familiar with this disease. DSRCT in young patients can be mistaken for other abdominal tumors including rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroblastoma, and mesenteric carcinoid. In older patients DSRCT can resemble lymphoma, peritoneal mesothelioma, and peritoneal carcinomatosis. In males DSRCT may be mistaken for germ cell or testicular cancer while in females DSRCT can be mistaken for Ovarian cancer. DSRCT shares characteristics with other small-round blue cell cancers including Ewing's sarcoma, acute leukemia, small cell mesothelioma, neuroblastoma, primitive neuroectodermal tumor, rhabdomyosarcoma, and Wilms' tumor.

Treatment

DSRCT is frequently misdiagnosed. Adult patients should always be referred to a sarcoma specialist. This is an aggressive, rare, fast spreading tumor and both pediatric and adult patients should be treated at a sarcoma center.

There is no standard protocol for the disease;[9] however, recent journals and studies have reported that some patients respond to high-dose (P6 Protocol) chemotherapy, maintenance chemotherapy, debulking operation, cytoreductive surgery, and radiation therapy.

Other treatment options include: hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, intensity-modulated radiation therapy, radiofrequency ablation, stereotactic body radiation therapy, intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemoperfusion, and clinical trials.

Prognosis

The prognosis for DSRCT remains poor.[1]

Prognosis depends upon the stage of the cancer. Because the disease can be misdiagnosed or remain undetected, tumors frequently grow large within the abdomen and metastasize or seed to other parts of the body. There is no known organ or area of origin. DSRCT can metastasize through lymph nodes or the blood stream. Sites of metastasis include the spleen, diaphragm, liver, large and small intestine, lungs, central nervous system, bones, uterus, bladder, genitals, abdominal cavity, and the brain.

A multi-modality approach of high-dose chemotherapy, aggressive surgical resection,[10] radiation, and stem cell rescue improves survival for some patients. Reports have indicated that patients will initially respond to first line chemotherapy and treatment but that relapse is common.

Some patients in remission or with inoperable tumor seem to benefit from long term low dose chemotherapy, turning DSRCT into a chronic disease.

Research

The Stehlin Foundation[11] currently offers DSRCT patients the opportunity to send samples of their tumors free of charge for testing. Research scientists are growing the samples on nude mice and testing various chemical agents to find which are most effective against the individual's tumor.

Patients with advanced DSRCT may qualify to participate in clinical trials that are researching new drugs to treat the disease.

The Cory Monzingo Foundation Archived 2019-01-12 at the Wayback Machine is a 501(c)(3) organization that supports the research for treatments and a cure for DSRCT. The Cory Monzingo Foundation provides funding to MD Anderson Cancer Center and may also provide funding to other nonprofit cancer research organizations.

In 2002, Nishio and al,[12] established a novel human tumor cell line derived from the pleural effusion of a patient with a typical intra-abdominal DSRCT, called JN-DSRCT-1[13] that can now be used in research.

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital has, in 2018, make available resources from the Childhood Solid Tumor Network, that upon request gives access to patient-derived orthotopic xenografts.[14]

Alternative names

This disease is also known as: desmoplastic small round blue cell tumor; intra-abdominal desmoplastic small round blue cell tumor; desmoplastic small cell tumor; desmoplastic cancer; desmoplastic sarcoma; DSRCT.

There is no connection to peritoneal mesothelioma which is another disease sometimes described as desmoplastic.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board, ed. (2020). "1. Soft tissue tumors: Tumors of uncertain differentiation - Desmoplastic small-round-cell tumor". Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours: WHO Classification of Tumours. Vol. 3 (5th ed.). Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer. pp. 306–308. ISBN 978-92-832-4503-2. Archived from the original on 2021-06-13. Retrieved 2022-06-20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Desmoplastic Small Round Cell Tumors (DSRCT)". www.cancer.gov. 16 September 2019. Archived from the original on 13 June 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ↑ "Orphanet: Desmoplastic small round cell tumor". www.orpha.net. Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ↑ Murphy AJ, Bishop K, Pereira C, et al. (December 2008). "A new molecular variant of desmoplastic small round cell tumor: significance of WT1 immunostaining in this entity". Hum. Pathol. 39 (12): 1763–70. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2008.04.019. PMID 18703217.

- ↑ Gerald WL, Haber DA (June 2005). "The EWS-WT1 gene fusion in desmoplastic small round cell tumor". Semin. Cancer Biol. 15 (3): 197–205. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.01.005. PMID 15826834.

- ↑ Lee YS, Hsiao CH (2007). "Desmoplastic small round cell tumor: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical and molecular study of four patients". J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 106 (10): 854–60. doi:10.1016/S0929-6646(08)60051-0. PMID 17964965.

- ↑ Li H, Smolen GA, Beers LF, et al. (2008). "Adenosine transporter ENT4 is a direct target of EWS/WT1 translocation product and is highly expressed in desmoplastic small round cell tumor". PLOS ONE. 3 (6): e2353. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.2353L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002353. PMC 2394657. PMID 18523561.

- ↑ Gerald, W. L.; Rosai, J. (1989). "Case 2. Desmoplastic small cell tumor with divergent differentiation". Pediatr. Pathol. 9 (2): 177–83. doi:10.3109/15513818909022347. PMID 2473463.

- ↑ Talarico F, Iusco D, Negri L, Belinelli D: Combined resection and multi-agent adjuvant chemotherapy for intra-abdominal desmoplastic small round cell tumour: case report and review of the literature. G Chir 2007; 28: 367–370.

- ↑ Talarico F, Iusco D, Negri L, Belinelli D (October 2007). "Combined resection and multi-agent adjuvant chemotherapy for intra-abdominal desmoplastic small round cell tumour: case report and review of the literature". G Chir. 28 (10): 367–70. PMID 17915050. Archived from the original on 2021-04-21. Retrieved 2021-08-27.

- ↑ "Official website for Stehlin Foundation". Archived from the original on 2021-04-12. Retrieved 2022-03-14.

- ↑ Nishio, Jun; Iwasaki, Hiroshi; Ishiguro, Masako; Ohjimi, Yuko; Fujita, Chikako; Yanai, Fumio; Nibu, Keiko; Mitsudome, Akihisa; Kaneko, Yasuhiko (September 2002). "Establishment and characterization of a novel human desmoplastic small round cell tumor cell line, JN-DSRCT-1". Laboratory Investigation; A Journal of Technical Methods and Pathology. 82 (9): 1175–1182. doi:10.1097/01.LAB.0000028059.92642.03. ISSN 0023-6837. PMID 12218078.

- ↑ "Jn-Dsrct-1". Archived from the original on 2019-04-21. Retrieved 2021-08-27.

- ↑ "St Jude Children's Research Hospital". Archived from the original on 2021-01-23. Retrieved 2021-08-27.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|