Liver cancer

| Liver cancer | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Hepatic cancer, primary hepatic malignancy, primary liver cancer, hepatoma | |

| |

| CT scan of a liver with cholangiocarcinoma | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

| Symptoms | Lump or pain in the right side below the rib cage, swelling of the abdomen, yellowish skin, easy bruising, weight loss, weakness[1] |

| Usual onset | 55 to 65 years old[2] |

| Causes | Cirrhosis due to hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or alcohol, aflatoxin, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, liver flukes[3][4] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood tests, medical imaging, tissue biopsy[1] |

| Prevention | Immunization against hepatitis B, treating those infected with hepatitis B or C[3] |

| Treatment | Surgery, targeted therapy, radiation therapy[1] |

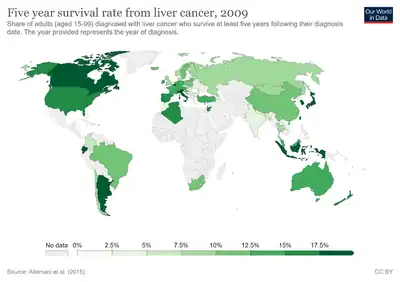

| Prognosis | Five-year survival rates ~18% (US);[2] 40% (Japan)[5] |

| Frequency | 618,700 (point in time in 2015)[6] |

| Deaths | 782,000 (2018)[7] |

Liver cancer, also known as hepatic cancer, is cancer that starts in the liver.[1] Cancer which has spread from elsewhere to the liver, known as liver metastasis, is more common than that which starts in the liver.[3] Symptoms of liver cancer may include a lump or pain in the right side below the rib cage, swelling of the abdomen, yellowish skin, easy bruising, weight loss and weakness.[1]

The leading cause of liver cancer is cirrhosis due to hepatitis B, hepatitis C or alcohol.[4] Other causes include aflatoxin, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and liver flukes.[3] The most common types are hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which makes up 80% of cases, and cholangiocarcinoma.[3] Less common types include mucinous cystic neoplasm and intraductal papillary biliary neoplasm.[3] The diagnosis may be supported by blood tests and medical imaging, with confirmation by tissue biopsy.[1]

Preventive efforts include immunization against hepatitis B and treating those infected with hepatitis B or C.[3] Screening is recommended in those with chronic liver disease.[3] Treatment options may include surgery, targeted therapy and radiation therapy.[1] In certain cases, ablation therapy, embolization therapy or liver transplantation may be used.[1] Small lumps in the liver may be closely followed.[1]

Primary liver cancer is globally the sixth-most frequent cancer (6%) and the second-leading cause of death from cancer (9%).[3][8] In 2018, it occurred in 841,000 people and resulted in 782,000 deaths.[7] In 2015, 263,000 deaths from liver cancer were due to hepatitis B, 245,000 to alcohol and 167,000 to hepatitis C.[9] Higher rates of liver cancer occur where hepatitis B and C are common, including Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.[3] Males are more often affected with HCC than females.[3] Diagnosis is most frequent among those 55 to 65 years old.[2] Five-year survival rate is 18.4 % in the United States,[2] and 40.4% in Japan.[5] The word "hepatic" is from the Greek hêpar, meaning "liver".[10]

Signs and symptoms

Because liver cancer is an umbrella term for many types of cancer, the signs and symptoms depend on what type of cancer is present. Cholangiocarcinoma is associated with sweating, jaundice, abdominal pain, weight loss and liver enlargement.[11] Hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with abdominal mass, abdominal pain, emesis, anemia, back pain, jaundice, itching, weight loss and fever.[12]

Causes

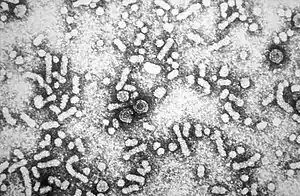

Viral infection

Viral infection with either hepatitis C virus (HCV) or Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is the chief cause of liver cancer in the world today, accounting for 80% of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).[13][14][15] The viruses cause HCC because massive inflammation, fibrosis, and eventual cirrhosis occurs within the liver. HCC usually arises after cirrhosis, with an annual incidence of 1.7% in cirrhotic HCV-infected individuals.[16] Around 5-10% of individuals that become infected with HBV become chronic carriers, and around 30% of these acquire chronic liver disease, which can lead to HCC.[13] HBV infection is also linked to cholangiocarcinoma.[17] The role of viruses other than HCV or HBV in liver cancer is much less clear, even though there is some evidence that co-infection of HBV and hepatitis D virus may increase the risk for HCC.[18]

Many genetic and epigenetic changes are formed in liver cells during HCV and HBV infection, which is a major factor in the production of the liver tumors. The viruses induce malignant changes in cells by altering gene methylation, affecting gene expression, and promoting or repressing cellular signal transduction pathways. By doing this, the viruses can prevent cells from undergoing a programmed form of cell death (apoptosis) and promote viral replication and persistence.[13][16]

HBV and HCV also induce malignant changes by causing DNA damage and genomic instability. This is by creating reactive oxygen species, express proteins that interfere with DNA repair enzymes, and HCV causes activation of a mutator enzyme.[19][20]

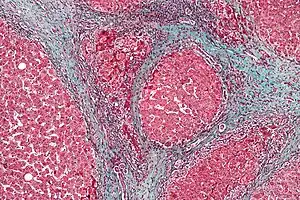

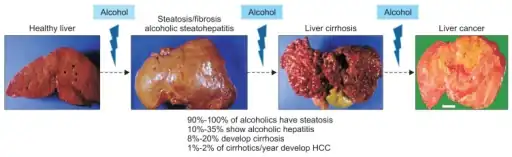

Cirrhosis

In addition to virus-related cirrhosis described above, other causes of cirrhosis can lead to HCC. Alcohol intake correlates with risk of HCC, and the risk is far greater in individuals with an alcohol-induced cirrhotic liver. There are a few disorders that are known to cause cirrhosis and lead to cancer, including hereditary hemochromatosis and primary biliary cirrhosis.[21]

Progression for alcoholic liver injury to steatosis with scarring, and architectural distortion leading to cirrhosis; as a complication of cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma may occur

Progression for alcoholic liver injury to steatosis with scarring, and architectural distortion leading to cirrhosis; as a complication of cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma may occur

Aflatoxin

Aflatoxin exposure can lead to the development of HCC. The aflatoxins are a group of chemicals produced by the fungi Aspergillus flavus (the name comes from A. flavus toxin) and A. parasiticus. Food contamination by the fungi leads to ingestion of the chemicals, which are very toxic to the liver. Common foodstuffs contaminated with the toxins are cereals, peanuts, and other vegetables. Contamination of food is common in Africa, South-East Asia, and China. Concurrent HBV infection and aflatoxin exposure increases the risk for liver cancer to over three times that seen in HBV infected individuals without aflatoxin exposure. The mechanism by which aflatoxins cause cancer is through mutations and epigenetic alterations. Aflatoxins induce a spectrum of mutations[22][23] including a very frequent mutation in the p53 tumor suppressor gene.[22] Mutation in p53, presumably in conjunction with other aflatoxin-induced mutations and epigenetic alterations,[24] is likely a common cause of aflatoxin-induced carcinogenesis.

Other causes in adults

- High grade dysplastic nodules are precancerous lesions of the liver. Within two years, there is a risk for cancer arising from these nodules of 30–40%.[25]

- Obesity has emerged as an important risk factor, as it can lead to steatohepatitis.[15][26]

- Diabetes increases the risk for HCC.[26]

- Smoking increases the risk for HCC compared to non-smokers and previous smokers.[26]

- There is around 5-10% lifetime risk of cholangiocarcinoma in people with primary sclerosing cholangitis.[27]

- Liver fluke infection increases the risk for cholangiocarcinoma, and this is the reason why Thailand has particularly high rates of this cancer.[28]

Children

Increased risk for liver cancer in children can be caused by Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome (associated with hepatoblastoma),[29][30] familial adenomatous polyposis (associated with hepatoblastoma),[30] low birth weight (associated with hepatoblastoma),[31] Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (associated with HCC)[32] and Trisomy 18 (associated with hepatoblastoma).[30]

Diagnosis

Many imaging modalities are used to aid in the diagnosis of primary liver cancer. For HCC these include medical ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). When imaging the liver with ultrasound, a mass greater than 2 cm has more than 95% chance of being HCC. The majority of cholangiocarcimas occur in the hilar region of the liver, and often present as bile duct obstruction. If the cause of obstruction is suspected to be malignant, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), ultrasound, CT, MRI and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) are used.[33]

Tumor markers, chemicals sometimes found in the blood of people with cancer, can be helpful in diagnosing and monitoring the course of liver cancers. High levels of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) in the blood can be found in many cases of HCC and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cholangiocarcinoma can be detected with these commonly used tumor markers: carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and cancer antigen 125 (CA125). These tumour markers are found in primary liver cancers, as well as in other cancers and certain other disorders.[34][35]

Classification

The most frequent liver cancer, accounting for approximately 75% of all primary liver cancers, is hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (also named hepatoma, which is a misnomer because adenomas are usually benign). HCC is a cancer formed by liver cells, known as hepatocytes, that become malignant. Another type of cancer formed by liver cells is hepatoblastoma, which is specifically formed by immature liver cells.[37] It is a rare malignant tumor that primarily develops in children, and accounts for approximately 1% of all cancers in children and 79% of all primary liver cancers under the age of 15. Most hepatoblastomas form in the right lobe.[31]

Liver cancer can also come from other structures within the liver such as the bile duct, blood vessels and immune cells. Cancer of the bile duct (cholangiocarcinoma and cholangiocellular cystadenocarcinoma) account for approximately 6% of primary liver cancers.[37] There is also a variant type of HCC that consists of both HCC and cholangiocarcinoma.[38] Tumors of the blood vessels (angiosarcoma and hemangioendothelioma, embryonal sarcoma and fibrosarcoma are produced from a type of connective tissue known as mesenchyme. Cancers produced from muscle in the liver are leiomyosarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma. Other less common liver cancers include carcinosarcomas, teratomas, yolk sac tumours, carcinoid tumours and lymphomas.[37] Lymphomas usually have diffuse infiltration to liver, but It may also form a liver mass in rare occasions.

Many cancers found in the liver are not true liver cancers but are cancers from other sites in the body that have spread to the liver (known as metastases). Frequently, the site of origin is the gastrointestinal tract, since the liver is close to many of these metabolically active, blood-rich organs near to blood vessels and lymph nodes (such as pancreatic cancer, stomach cancer, colon cancer and carcinoid tumors mainly of the appendix), but also from breast cancer, ovarian cancer, lung cancer, renal cancer, prostate cancer.

Prevention

Prevention of cancers can be separated into primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention. Primary prevention preemptively reduces exposure to a risk factor for liver cancer. One of the most successful primary liver cancer preventions is vaccination against hepatitis B. Vaccination against the hepatitis C virus is currently unavailable. Other forms of primary prevention are aimed at limiting transmission of these viruses by promoting safe injection practices, screening blood donation products, and screening high-risk asymptomatic individuals. Aflatoxin exposure can be avoided by post-harvest intervention to discourage mold, which has been effective in west Africa. Reducing alcohol abuse, obesity, and diabetes would also reduce rates of liver cancer. Diet control in hemochromatosis could decrease the risk of iron overload, decreasing the risk of cancer.[39]

Secondary prevention includes both cure of the agent involved in the formation of cancer (carcinogenesis) and the prevention of carcinogenesis if this is not possible. Cure of virus-infected individuals is not possible, but treatment with antiviral drugs such as interferon can decrease the risk of liver cancer. Chlorophyllin may have potential in reducing the effects of aflatoxin.[39]

Tertiary prevention includes treatments to prevent the recurrence of liver cancer. These include the use of chemotherapy drugs and antiviral drugs.[39]

Treatment

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Partial surgical resection is the optimal treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) when patients have sufficient hepatic function reserve. Increased risk of complications such as liver failure can occur with resection of cirrhotic (i.e. less-than-optimally functional) livers. 5-year survival rates after resection have massively improved over the last few decades and can now exceed 50%. However, recurrence rates after resection can exceed 70%, whether due to spread of the initial tumor or formation of new tumors .[40] Liver transplantation can also be considered in cases of HCC where this form of treatment can be tolerated and the tumor fits specific criteria (such as the Milan criteria). In general, patients who are being considered for liver transplantation have multiple hepatic lesions, severe underlying liver dysfunction, or both. Less than 30–40% of individuals with HCC are eligible for surgery and transplant because the cancer is often detected at a late stage. Also, HCC can progress during the waiting time for liver transplants, which can prevent transplant due to the strict criteria.

Percutaneous ablation is the only non-surgical treatment that can offer cure. There are many forms of percutaneous ablation, which consist of either injecting chemicals into the liver (ethanol or acetic acid) or producing extremes of temperature using radio frequency ablation, microwaves, lasers or cryotherapy. Of these, radio frequency ablation has one of the best reputations in HCC, but the limitations include inability to treat tumors close to other organs and blood vessels due to heat generation and the heat sink effect, respectively.[41][42] In addition, long-term of outcomes of percutaneous ablation procedures for HCC have not been well studied. In general, surgery is the preferred treatment modality when possible.

Systemic chemotherapeutics are not routinely used in HCC, although local chemotherapy may be used in a procedure known as transarterial chemoembolization. In this procedure, cytotoxic drugs such as doxorubicin or cisplatin with lipiodol are administered and the arteries supplying the liver are blocked by gelatin sponge or other particles. Because most systemic drugs have no efficacy in the treatment of HCC, research into the molecular pathways involved in the production of liver cancer produced sorafenib, a targeted therapy drug that prevents cell proliferation and blood cell growth. Sorafenib obtained FDA approval for the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in November 2007.[43] This drug provides a survival benefit for advanced HCC.[42]

Radiotherapy is not often used in HCC because the liver is not tolerant to radiation. Although with modern technology it is possible to provide well-targeted radiation to the tumor, minimizing the dose to the rest of the liver. Dual treatments of radiotherapy plus chemoembolization, local chemotherapy, systemic chemotherapy or targeted therapy drugs may show benefit over radiotherapy alone.[44]

Cholangiocarcinoma

Resection is an option in cholangiocarcinoma, but fewer than 30% of cases of cholangiocarcinoma are resectable at diagnosis. After surgery, recurrence rates are up to 60%.[45][46] Liver transplant may be used where partial resection is not an option, and adjuvant chemoradiation may benefit some cases.[27]

60% of cholangiocarcinomas form in the perihilar region and photodynamic therapy can be used to improve quality of life and survival time in these unresectable cases. Photodynamic therapy is a novel treatment that utilitizes light activated molecules to treat the tumor. The compounds are activated in the tumor region by laser light, which causes the release of toxic reactive oxygen species, killing tumor cells.[45][47]

Systemic chemotherapies such as gemcitabine and cisplatin are sometimes used in inoperable cases of cholangiocarcinoma.[27]

Radio frequency ablation, transarterial chemoembolization and internal radiotherapy (brachytherapy) all show promise in the treatment of cholangiocarcinoma.[46]

Radiotherapy may be used in the adjuvant setting or for palliative treatment of cholangiocarcinoma.[48]

Hepatoblastoma

Removing the tumor by either surgical resection or liver transplant can be used in the treatment of hepatoblastoma. In some cases surgery can offer a cure. Chemotherapy may be used before and after surgery and transplant.[49]

Chemotherapy, including cisplatin, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin are used for the systemic treatment of hepatoblastoma. Out of these drugs, cisplatin seems to be the most effective.[50]

Epidemiology

Globally, as of 2010, liver cancer resulted in 754,000 deaths, up from 460,000 in 1990, making it the third leading cause of cancer death after lung and stomach.[51] In 2012, it represented 7% of cancer diagnoses in men, the 5th most diagnosed cancer that year.[52] Of these deaths 340,000 were secondary to hepatitis B, 196,000 were secondary to hepatitis C, and 150,000 were secondary to alcohol.[51] HCC, the most common form of liver cancer, shows a striking geographical distribution. China has 50% of HCC cases globally, and more than 80% of total cases occur in sub-Saharan Africa or in East-Asia due to hepatitis B virus.[28][53] Cholangiocarcinoma also has a significant geographical distribution, with Thailand showing the highest rates worldwide due to the presence of liver fluke.[28][54]

India

The number of new cases of hepatocellular carcinoma per year in India in males is about 4.1 and for females 1.2 per 100,000. It typically occurs between 40 and 70 years of age.[55]

United Kingdom

Liver cancer is the eighteenth most common cancer in the UK (around 4,300 people were diagnosed with liver cancer in the UK in 2011), and it is the twelfth most common cause of cancer death (around 4,500 people died of the disease in 2012).[56]

United States

Liver cancer death rates for adults aged 25 and over increased 43 percent from 7.2 per 100,000 U.S. standard population in 2000 to 10.3 in 2016. Liver cancer death rates increased 43 percent from 10.5 in 2000 to 15.0 in 2016 for men and 40 percent from 4.5 to 6.3 for women. The death rate for men was between 2.0–2.5 times the rate for women throughout this period.[57]

Research

Hepcortespenlisimut-L is an oral immunotherapy that is going through a phase 3 clinical trial for HCC.[58]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Adult Primary Liver Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)–Patient Version". NCI. 6 July 2016. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Liver and Intrahepatic Bile Duct Cancer". NCI. Archived from the original on 2017-07-28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 5.6. ISBN 978-9283204299.

- 1 2 GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- 1 2 "がん診療連携拠点病院等院内がん登録生存率集計:[国立がん研究センター がん登録・統計]". ganjoho.jp. Archived from the original on 16 September 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ↑ GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- 1 2 Bray, F; Ferlay, J; Soerjomataram, I; Siegel, RL; Torre, LA; Jemal, A (November 2018). "Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 68 (6): 394–424. doi:10.3322/caac.21492. PMID 30207593. Archived from the original on 2021-04-17. Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- ↑ World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 1.1. ISBN 978-9283204299.

- ↑ GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ↑ "Hepato- Etymology". dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2015. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ↑ Cholangiocarcinoma at eMedicine

- ↑ "Liver tumors in Children". Boston Children's Hospital. Archived from the original on 2011-06-04.

- 1 2 3 Arzumanyan, A; Reis, HM; Feitelson, MA (February 2013). "Pathogenic mechanisms in HBV- and HCV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 13 (2): 123–35. doi:10.1038/nrc3449. PMID 23344543.

- ↑ Rosen, HR (Jun 23, 2011). "Clinical practice. Chronic hepatitis C infection". The New England Journal of Medicine. 364 (25): 2429–38. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1006613. PMID 21696309. Archived from the original on August 28, 2021. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- 1 2 "General Information About Adult Primary Liver Cancer". National Cancer Institute. 1980-01-01. Archived from the original on 2 January 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- 1 2 Jeong, SW; Jang, JY; Chung, RT (December 2012). "Hepatitis C virus and hepatocarcinogenesis". Clinical and Molecular Hepatology. 18 (4): 347–56. doi:10.3350/cmh.2012.18.4.347. PMC 3540370. PMID 23323249.

- ↑ Ralphs, S; Khan, SA (May 2013). "The role of the hepatitis viruses in cholangiocarcinoma". Journal of Viral Hepatitis. 20 (5): 297–305. doi:10.1111/jvh.12093. PMID 23565610.

- ↑ Kew, MC (March 2013). "Hepatitis viruses (other than hepatitis B and C viruses) as causes of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update". Journal of Viral Hepatitis. 20 (3): 149–57. doi:10.1111/jvh.12043. PMID 23383653.

- ↑ Takeda H, Takai A, Inuzuka T, Marusawa H (2017). "Genetic basis of hepatitis virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma: linkage between infection, inflammation, and tumorigenesis". J. Gastroenterol. 52 (1): 26–38. doi:10.1007/s00535-016-1273-2. PMID 27714455.

- ↑ Yang, SF; Chang, CW; Wei, RJ; Shiue, YL; Wang, SN; Yeh, YT (2014). "Involvement of DNA damage response pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma". BioMed Research International. 2014: 153867. doi:10.1155/2014/153867. PMC 4022277. PMID 24877058.

- ↑ Fattovich, G; Stroffolini, T; Zagni, I; Donato, F (November 2004). "Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: incidence and risk factors". Gastroenterology. 127 (5 Suppl 1): S35–50. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.014. PMID 15508101.

- 1 2 Smela ME, Currier SS, Bailey EA, Essigmann JM (April 2001). "The chemistry and biology of aflatoxin B(1): from mutational spectrometry to carcinogenesis". Carcinogenesis. 22 (4): 535–45. doi:10.1093/carcin/22.4.535. PMID 11285186.

- ↑ Perduca V, Omichessan H, Baglietto L, Severi G (January 2018). "Mutational and epigenetic signatures in cancer tissue linked to environmental exposures and lifestyle". Curr Opin Oncol. 30 (1): 61–67. doi:10.1097/CCO.0000000000000418. PMID 29076965.

- ↑ Dai Y, Huang K, Zhang B, Zhu L, Xu W (November 2017). "Aflatoxin B1-induced epigenetic alterations: An overview". Food Chem. Toxicol. 109 (Pt 1): 683–689. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2017.06.034. PMID 28645871.

- ↑ Di Tommaso, L; Sangiovanni, A; Borzio, M; Park, YN; Farinati, F; Roncalli, M (April 2013). "Advanced precancerous lesions in the liver". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Gastroenterology. 27 (2): 269–84. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2013.03.015. PMID 23809245.

- 1 2 3 Chuang SC, La Vecchia C, Boffetta P (Dec 1, 2009). "Liver cancer: descriptive epidemiology and risk factors other than HBV and HCV infection". Cancer Letters. 286 (1): 9–14. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2008.10.040. PMID 19091458.

- 1 2 3 Razumilava, N; Gores, GJ (January 2013). "Classification, diagnosis, and management of cholangiocarcinoma". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 11 (1): 13–21.e1, quiz e3–4. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2012.09.009. PMC 3596004. PMID 22982100.

- 1 2 3 Jemal, A; Bray, F; Center, MM; Ferlay, J; Ward, E; Forman, D (Mar–Apr 2011). "Global cancer statistics". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 61 (2): 69–90. doi:10.3322/caac.20107. PMID 21296855. Archived from the original on 2020-12-04. Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- ↑ DeBaun, MR; Tucker, MA (March 1998). "Risk of cancer during the first four years of life in children from The Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome Registry". The Journal of Pediatrics. 132 (3 Pt 1): 398–400. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(98)70008-3. PMID 9544889. Archived from the original on 2019-05-27. Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- 1 2 3 Spector, LG; Birch, J (November 2012). "The epidemiology of hepatoblastoma". Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 59 (5): 776–9. doi:10.1002/pbc.24215. PMID 22692949. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- 1 2 Emre, S; McKenna, GJ (December 2004). "Liver tumors in children". Pediatric Transplantation. 8 (6): 632–8. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3046.2004.00268.x. PMID 15598339.

- ↑ Davit-Spraul, A; Gonzales, E; Baussan, C; Jacquemin, E (Jan 8, 2009). "Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 4: 1. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-4-1. PMC 2647530. PMID 19133130.

- ↑ Ariff, B; Lloyd, CR; Khan, S; Shariff, M; Thillainayagam, AV; Bansi, DS; Khan, SA; Taylor-Robinson, SD; Lim, AK (Mar 21, 2009). "Imaging of liver cancer". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 15 (11): 1289–300. doi:10.3748/wjg.15.1289. PMC 2658841. PMID 19294758.

- ↑ Malaguarnera, G; Paladina, I; Giordano, M; Malaguarnera, M; Bertino, G; Berretta, M (2013). "Serum markers of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma". Disease Markers. 34 (4): 219–28. doi:10.1155/2013/196412. PMC 3809974. PMID 23396291.

- ↑ Zhao YJ, Ju Q, Li GC (2013). "Tumor markers for hepatocellular carcinoma". Mol Clin Oncol. 1 (4): 593–598. doi:10.3892/mco.2013.119. PMC 3915636. PMID 24649215.

- ↑ Table 37.2 Archived 2020-02-24 at the Wayback Machine in: Sternberg, Stephen (2012). Sternberg's diagnostic surgical pathology. Place of publication not identified: LWW. ISBN 978-1-4511-5289-0. OCLC 953861627.

- 1 2 3 Ahmed, Ahmed, I; Lobo D.N.; Lobo, Dileep N. (January 2009). "Malignant tumours of the liver". Surgery (Oxford). 27 (1): 30–37. doi:10.1016/j.mpsur.2008.12.005.

- ↑ Khan SA, Davidson BR, Goldin RD, Heaton N, Karani J, Pereira SP, Rosenberg WM, Tait P, Taylor-Robinson SD, Thillainayagam AV, Thomas HC, Wasan H (2012). "Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cholangiocarcinoma: an update". Gut. 61 (12): 1657–69. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301748. PMID 22895392.

- 1 2 3 Hoshida, Y; Fuchs, BC; Tanabe, KK (Nov 1, 2012). "Prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma: potential targets, experimental models, and clinical challenges". Current Cancer Drug Targets. 12 (9): 1129–59. doi:10.2174/156800912803987977. PMC 3776581. PMID 22873223.

- ↑ Bruix J, Sherman M, American Association for the Study of Liver, Diseases (March 2011). "Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update". Hepatology. 53 (3): 1020–2. doi:10.1002/hep.24199. PMC 3084991. PMID 21374666.

- ↑ Wang, ZG; Zhang, GF; Wu, JC; Jia, MK (August 2013). "Adjuvant therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: Current situation and prospect". Drug Discoveries & Therapeutics. 7 (4): 137–143. doi:10.5582/ddt.2013.v7.4.137. PMID 24071575.

- 1 2 de Lope, CR; Tremosini, S; Forner, A; Reig, M; Bruix, J (2012). "Management of HCC". Journal of Hepatology. 56 Suppl 1: S75–87. doi:10.1016/S0168-8278(12)60009-9. PMID 22300468.

- ↑ Keating GM, Santoro A (2009). "Sorafenib: a review of its use in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma". Drugs. 69 (2): 223–40. doi:10.2165/00003495-200969020-00006. PMID 19228077.

- ↑ Feng, M; Ben-Josef, E (October 2011). "Radiation therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma". Seminars in Radiation Oncology. 21 (4): 271–7. doi:10.1016/j.semradonc.2011.05.002. PMID 21939856.

- 1 2 Ulstrup, T; Pedersen, FM (Feb 25, 2013). "[Photodynamic therapy of cholangiocarcinomas]". Ugeskrift for Laeger. 175 (9): 579–82. PMID 23608009.

- 1 2 Kuhlmann, JB; Blum, HE (May 2013). "Locoregional therapy for cholangiocarcinoma". Current Opinion in Gastroenterology. 29 (3): 324–8. doi:10.1097/MOG.0b013e32835d9dea. PMID 23337933.

- ↑ Ortner, MA (September 2011). "Photodynamic therapy for cholangiocarcinoma". Lasers in Surgery and Medicine. 43 (7): 776–80. doi:10.1002/lsm.21106. PMID 22057505.

- ↑ Valero V, 3rd; Cosgrove, D; Herman, JM; Pawlik, TM (August 2012). "Management of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma in the era of multimodal therapy". Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 6 (4): 481–95. doi:10.1586/egh.12.20. PMC 3538366. PMID 22928900.

- ↑ Meyers, RL; Czauderna, P; Otte, JB (November 2012). "Surgical treatment of hepatoblastoma". Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 59 (5): 800–8. doi:10.1002/pbc.24220. PMID 22887704.

- ↑ Perilongo, G; Malogolowkin, M; Feusner, J (November 2012). "Hepatoblastoma clinical research: lessons learned and future challenges". Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 59 (5): 818–21. doi:10.1002/pbc.24217. PMID 22678761.

- 1 2 Lozano, R; Naghavi, M; Foreman, K; Lim, S; Shibuya, K; Aboyans, V; Abraham, J; Adair, T; Aggarwal, R; Ahn, S. Y.; Alvarado, M; Anderson, H. R.; Anderson, L. M.; Andrews, K. G.; Atkinson, C; Baddour, L. M.; Barker-Collo, S; Bartels, D. H.; Bell, M. L.; Benjamin, E. J.; Bennett, D; Bhalla, K; Bikbov, B; Bin Abdulhak, A; Birbeck, G; Blyth, F; Bolliger, I; Boufous, S; Bucello, C; et al. (Dec 15, 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30050819. PMID 23245604.

- ↑ World Cancer Report 2014. International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization. 2014. ISBN 978-92-832-0432-9.

- ↑ El-Serag, HB; Rudolph, KL (June 2007). "Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis". Gastroenterology. 132 (7): 2557–76. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.061. PMID 17570226.

- ↑ Khan, SA; Toledano, MB; Taylor-Robinson, SD (2008). "Epidemiology, risk factors, and pathogenesis of cholangiocarcinoma". HPB. 10 (2): 77–82. doi:10.1080/13651820801992641. PMC 2504381. PMID 18773060.

- ↑ "Overview of Hepatocellular Carcinoma". Liver Cancer. Archived from the original on 18 March 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- ↑ "Liver cancer statistics". Cancer Research UK. Archived from the original on 17 October 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- ↑ Xu, Jiaquan (July 2018). Trends in Liver Cancer Mortality Among Adults Aged 25 and Over in the United States, 2000–2016. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ↑ Immunitor Phase 3 trial of hepcortespenlisimut-L, Liver Cancer Immunotherapy "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-05-30. Retrieved 2015-05-29.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- EASL Guideline Archived 2021-04-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Liver cancer information Archived 2011-06-22 at the Wayback Machine from Cancer Research UK