Necrobiosis lipoidica

| Necrobiosis lipoidica | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum[1] | |

| |

| Symptoms | Plaques with a yellow-brown central dip and sharply defined purplish border, ulceration, scale, usually on legs[2] |

| Causes | Females in 30s[1] |

| Risk factors | Diabetes, impaired glucose tolerance[1] |

| Treatment | Control sugars[2] |

| Medication | Topical corticosterid or calcineurin inhibitors, intralesional injection of triamcinolone[2] |

| Prognosis | Rarely squamous cell carcinoma[1] |

| Frequency | Female>male[1] |

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a granulomatous skin disease.[1] It typically presents with small, firm red bumps which develop into plaques with a yellow-brown central dip and sharply defined purplish border, usually on both shins of the legs.[1][2] There may be reduced sensation and excess sweating, which gives it a shiny appearance.[2] The lesion may be oval or irregular, have some scale and visible veins and can break down and ulcerate.[2]

It is sometimes associated with people with impaired glucose tolerance or diabetes.[1] The severity or control of diabetes in an individual does not affect who will or will not get NLD.[3] It can also be associated with rheumatoid arthritis.[4] Better maintenance of diabetes after being diagnosed with NLD will not change how quickly the NLD will resolve.

If a lesion has been present for a long time, there may be a risk of squamous cell carcinoma.[1]

It typically occurs in females in their 30s.[1] 60% occur in people with type I diabetes.[2]

Signs and symptoms

NL/NLD most frequently appears on the patient's shins, often on both legs, although it may also occur on forearms, hands, trunk, and, rarely, nipple, penis, and surgical sites. The lesions are often asymptomatic but may become tender and ulcerate when injured. The first symptom of NL is often a "bruised" appearance (erythema) that is not necessarily associated with a known injury. The extent to which NL is inherited is unknown.

NLD appears as a hardened, raised area of the skin. The center of the affected area usually has a yellowish tint while the area surrounding it is a dark pink. It is possible for the affected area to spread or turn into an open sore. When this happens the patient is at greater risk of developing ulcers. If an injury to the skin occurs on the affected area, it may not heal properly or it will leave a dark scar.

.jpg.webp) Necrobiosis lipoidica

Necrobiosis lipoidica.jpg.webp) Necrobiosis lipoidica

Necrobiosis lipoidica.jpg.webp) Necrobiosis lipoidica

Necrobiosis lipoidica.jpg.webp) Necrobiosis lipoidica

Necrobiosis lipoidica

Pathophysiology

Although the exact cause of this condition is not known, it is an inflammatory disorder characterised by collagen degeneration, combined with a granulomatous response. It always involves the dermis diffusely, and sometimes also involves the deeper fat layer. Commonly, dermal blood vessels are thickened (microangiopathy).[3]

It can be precipitated by local trauma, though it often occurs without any injury.[5]

Diagnosis

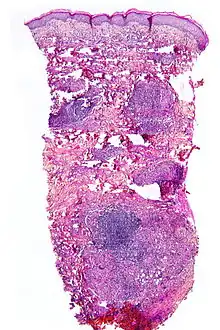

NL is diagnosed by a skin biopsy, demonstrating superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate (including lymphocytes, plasma cells, mononucleated and multinucleated histiocytes, and eosinophils) in the dermis and subcutis, as well as necrotising vasculitis with adjacent necrobiosis and necrosis of adnexal structures. Areas of necrobiosis are often more extensive and less well defined than in granuloma annulare. Presence of lipid in necrobiotic areas may be demonstrated by Sudan stains. Cholesterol clefts, fibrin, and mucin may also be present in areas of necrobiosis. Depending on the severity of the necrobiosis, certain cell types may be more predominant. When a lesion is in its early stages, neutrophils may be present, whereas in later stages of development lymphocytes and histiocytes may be more predominant.

Treatment

There is no clearly defined cure for necrobiosis.[6] NLD may be treated with PUVA therapy and improved therapeutic control.

Although there are some techniques that can be used to diminish the signs of necrobiosis such as low dose aspirin orally, a steroid cream or injection into the affected area, this process may be effective for only a small percentage of those treated.

See also

- Diabetic dermadromes

- List of cutaneous conditions

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Johnstone, Ronald B. (2017). "7. Granulomatous reaction pattern". Weedon's Skin Pathology Essentials (2nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-7020-6830-0. Archived from the original on 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2021-11-24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 James, William D.; Elston, Dirk; Treat, James R.; Rosenbach, Misha A.; Neuhaus, Isaac (2020). "26. Errors in metabolism". Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (13th ed.). Edinburgh: Elsevier. pp. 538–539. ISBN 978-0-323-54753-6.

- 1 2 Klaus J. Busam (15 January 2009). Dermatopathology. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-443-06654-2. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- ↑ James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6.

- ↑ Michael I. Greenberg (2005). Greenberg's text-atlas of emergency medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 416. ISBN 978-0-7817-4586-4. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- ↑ "AOCD Website". Archived from the original on 2013-04-30. Retrieved 2006-01-11.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Information and image at NIH Archived 2016-06-09 at the Wayback Machine