Parkes Weber syndrome

| Parkes Weber syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

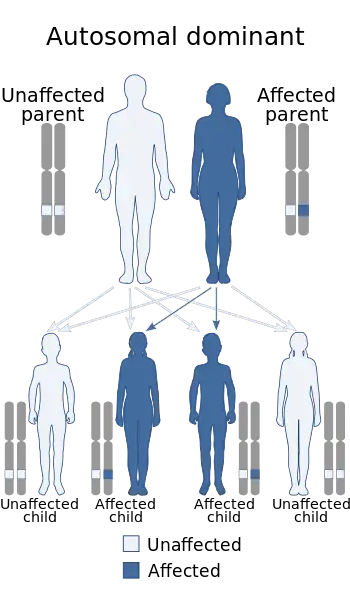

| Parkes Weber syndrome is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. | |

Parkes Weber syndrome (PWS) is a congenital disorder of the vascular system. It is an extremely rare condition, and its exact prevalence is unknown.[1][2][3] It is named after British dermatologist Frederick Parkes Weber, who first described the syndrome in 1907.[4]

In the body, the vascular system consists of arteries, veins and capillaries. When abnormalities such as vascular malformation, capillary arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs) and overgrowth of a limb occur together in combination and disturb the complex network of blood vessels of the vascular system, it is known as PWS.[5] The capillary malformations and AVFs are known to be present from the birth. In some cases, PWS is a genetic condition where the RASA1 gene is mutated and displays an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern.[6] If PWS is genetic then most patients show multiple capillary malformations. Patients who do not have multiple capillary malformations most likely did not inherit PWS and do not have RASA1 mutations. In such cases, the cause of PWS is often unknown and is sporadic as most cases often are.

PWS is often confused with Klippel–Trénaunay syndrome (KTS). These two diseases are similar, but they are distinct. PWS occurs because of vascular malformation that may or may not be because of genetic mutations, whereas Klippel-Trénaunay syndrome is a condition in which blood vessels and or lymph vessels do not form properly.[7] PWS and KTS almost have the same symptoms, except PWS patients are seen with both AVMs and AVFs occurring with limb hypertrophy.

Symptoms and signs

Major symptoms of PWS include:

Birthmarks: Affected PWS patients suffer from large, flat, pink staining on the skin. This staining is a result of the capillary malformations that have the tendency to increase the blood flow near the surface of the skin causing the staining. Because of the staining color they are sometimes referred to as "port-wine stains". "Port-wine stain" or discoloration of the skin due to vascular malformation is also referred as nevus flammeus.[5][8]

Hypertrophy: Hypertrophy refers to excessive growth of the bone and soft tissue. In PWS patients a limb is overgrown and hypertrophy is usually seen in the affected limb.[5]

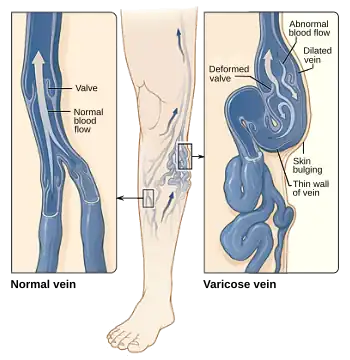

Multiple arteriovenous fistulas: PWS patients also suffer from multiple AVFs that occur in conjunction with capillary malformations. AVFs occur because of abnormal connections between arteries and veins.[5] Normally, blood flows from arteries to capillaries then to veins. But for AVF patients, because of the abnormal artery and vein connections, blood flows directly from arteries into the veins completely bypassing the capillaries.[9] These irregular connections affect the blood circulation and may lead to life-threatening complications such as abnormal bleeding and heart failure. AVFs can be identified by: large, purplish bulging veins, swelling in limbs, decreased in blood pressure, fatigue and heart failure.[9]

Capillary arteriovenous malformations: Vascular system disorder is the cause of the capillary malformations. Here, the capillaries are enlarged and increase the blood flow towards the surface of the skin.[10] Because of the capillary malformations, the skin has multiple small, round, pink or even red dots.[10] For most of the affected individuals, these malformations occur on the face, arms and or legs. The spots may be visible right from birth itself or they may develop during childhood years.[10] If capillary malformations occur by themselves, it is not a huge threat to life. But when these occur in conjunction with AVFs then it is a clear indicator of PWS and may be serious depending on the severity of the malformations.[10]

The Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) reports of additional symptoms in PWS patients. HPO is an active database that collects and researches on the relationships between phenotypic abnormalities and biochemical networks.[11] This is a useful database as it has information and data on some of the rarest diseases such as PWS. According to HPO, the symptoms which are reported very frequently in PWS patients include: abnormal bleeding, hypertrophy of the lower limb, hypertrophy of the upper limb, nevus flammeus or staining of the skin, peripheral arteriovenous fistula, telangiectasia of the skin. Frequent to occasional symptoms include: varicose veins, congestive heart failure, glaucoma and headache.

Abnormal bleeding: some skin lesions are prone to bleed easily.[11][12]

Peripheral arteriovenous fistula: abnormal communication between artery and vein that is a direct result of the abnormal connection or wiring between the artery and vein.[10][13]

Telangiectasia of the skin: Telangiectasia is a condition where tiny blood vessels become widened and form threadlike red lines and or patterns on the skin.[11] Because of their appearance and formation of web-like patterns they are also known as spider veins.[14] These patterns are referred as telangiectases.

Varicose veins: Enlarged, swollen and twisted veins.[11]

Congestive heart failure: This is a condition in which the heart’s ability to meet the requirements of the body is diminished. The cardiac output is decreased and the amount of blood pumped is not adequate enough to keep the circulation from the body and lungs going.[11][15]

Glaucoma: Glaucoma is a combination of diseases that cause damage to the optic nerve and may result in vision loss and blindness.[11][16]

Causes

The causes for PWS are either genetic or unknown. Some cases are a direct result of the RASA1 gene mutations. And individuals with RASA1 can be identified because this genetic mutation always causes multiple capillary malformations.[12] PWS displays an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance.[6] This means that one copy of the damaged or altered gene is sufficient to elicit PWS disorder. In most cases, PWS occurs in people that have no family history of the condition. In such cases the mutation is sporadic. And for patients with PWS with the absence of multiple capillary mutations, the causes are unknown.

According to Boston's Children Hospital, no known food, medications or drugs can cause PWS during pregnancy. PWS is not transmitted from person to person. But it can run in families and can be inherited. PWS affects both males and females equally and as of now no racial predominance is found.[17]

Mechanism

The causes for PWS without capillary malformations are currently unknown. Some cases of PWS are a result of mutations on the RASA1 gene which is located on chromosome 5 at position 14.3.[2][18][19] This mutation is only applicable to patients with capillary malformations. RASA1 gene is responsible for making p120-RasGAP protein.[20] This protein regulates the RAS/MAPK signaling pathway.[21] RAS/MAPK signaling pathway is used for transmitting signals from the outside the cell to the cell’s nucleus. This pathway is very important as it directs cell functions such as growth, proliferation and controls the cell movement.[18] The p120-RasGAP protein regulates the RAS/MAPK pathway by acting as a negative regulator of the signaling pathway.[20] It turns off signals.

Mutations in the RASA1 gene disrupt the normal formation of p120-RasGAP protein and result in a nonfunctional protein.[20] The protein no longer regulates the RAS/MAPK signaling pathway. However, according to NIH Genetics Home Reference, it is still unclear how exactly the disruption of p120-RasGAP protein formation leads to vascular abnormalities and limb overgrowth. But it is a known fact that somehow p120-RasGAP protein is crucial for the normal development of the vascular system and its complex network of blood vessels such as arteries, veins and capillaries.[20]

Based on current knowledge, disruption of p120-RasGAP protein is the reason behind blood vessel malformations which in turn lead to all sorts of problems such as: overgrowth in limbs, excess blood flow near the surface of the skin which leads to port wine stains and even heart failure can occur. The severity of the symptoms is based on extent of the malformations.

Diagnosis

Making a correct diagnosis for a genetic and rare disease is oftentimes very challenging. So the doctors and other healthcare professions rely on the person's medical history, the severity of the symptoms, physical examination and lab tests to make and confirm a diagnosis.[5]

There is a possibility of interpreting the symptoms of PWS with other conditions such as AVMs and or AVFs. This is because AVMs and AVFs also involve the characteristic overgrowth in soft tissue, bone and brain.[9][10] Also PWS can be misdiagnosed with Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome (KTS).[7] However, KTS consists of the following: triad capillary malformation, venous malformation, and lymphatic malformation.[22]

Usually a specific set of symptoms such as capillary and arteriovenous malformations occur together and this is used to distinguish PWS from similar conditions. Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) and arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs) are caused by RASA1 mutations as well. Therefore, if all the other tests (discussed below) fail to determine PWS, which is highly unlikely, genetic testing such as sequence analysis and gene-targeted deletion/duplication analysis can be performed to identify possible RASA1 gene mutations.[12]

PWS can be distinguished from other conditions because of its defining port-wine stains that are large, flat and pink. The port-wine stains and physical examination are enough to diagnose PWS.[23] But additional testing is necessary to determine the extent of the PWS syndrome. The following tests may be ordered by physicians to help determine the appropriate next steps: MRI, ultrasound, CT/CAT scan, angiogram, and echocardiogram.[23]

MRI: This is a high-resolution scan that is used to identify the extent of the hypertrophy or overgrowth of the tissues. This can also be used to identify other complications that may arise a result of hypertrophy.[23]

Ultrasound: this can be necessary to examine the vascular system and determine how much blood is actually flowing through the AVMs.[23]

CT/CAT scan: this scan is especially useful for examining the areas affected by PWS and is helpful for evaluating the bones in the overgrown limb.[23]

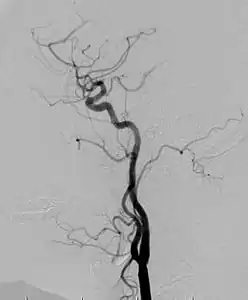

Angiogram: an angiogram can also be ordered to get a detailed look at the blood vessels in the affected or overgrown limb. In this test a physician injects a dye into the blood vessels that will help see how the blood vessels are malformed.[23]

Echocardiogram: depending on the intensity of the PWS syndrome, an echo could also be ordered to check the condition of the heart.[23]

PWS often requires a multidisciplinary care. Depending on the symptoms, patients are dependent on: dermatologists, plastic surgeons, general surgeons, interventional radiologists, orthopedists, hematologists, neurosurgeons, vascular surgeons and cardiologists.[24] Since the arteriovenous and capillary malformations cannot be completely reconstructed and depending on the extent and severity of the malformations, these patients may be in the care of physicians for their entire lives.

MRI-dilated turtuous blood vessels

MRI-dilated turtuous blood vessels Angiogram

Angiogram

Differential diagnosis

Prevention

At the moment, there are no known measures that can be taken in order to prevent the onset of the disorder. The Genetic Testing Registry is a resource for patients with PWS as it provides information on genetic tests that could be done to see if the patient has the necessary mutations.[5][26] If PWS is sporadic or does not have RASA1 mutation, then genetic testing will not work and there is not a way to prevent the onset of PWS.

Treatment

There is no cure for PWS.[5] Treatment differs from person to person and depends on the extent and severity of the blood vessels malformations and the degree of correction possible. The treatments can only control the symptoms and often involve a multidisciplinary care as mentioned in diagnosis.[24] AVMs and AVFs are treated with surgery or with embolization.[5] If there are differences in the legs because of overgrowth in the affected limb, then the patient is referred to an orthopedist.[5] If legs are affected to a minimal degree, then the patient may find heel inserts to be useful as they adjust for the different lengths in the legs and can walk normally. The port-wine stains may be treated by dermatologists.[24] Supportive care is necessary and may include compression garments. These garments are tight-fitting clothing on the affected limb and helps with reducing pain and swelling.[24] This can also help with protecting the limb from bumps and scrapes that cause bleeding. Again, based on the symptoms, the doctors may recommend antibiotics or pain medications.[24]

Surgical care might also be an option for PWS patients. Surgeons may perform debulking procedure in which abnormal and overgrown tissues are removed.[24] If PWS is affecting a foot or leg, the limbs can become quite large. And orthopedic surgeon can operate on the limb to reshape the limb. If the growth of the limb is more than one inch a procedure called epiphysiodesis may be performed.[24] This procedure interrupts the growth of the leg and stops the leg from growing too big.

Other treatment options include: embolization and laser therapy. Embolization includes a substance injected by an interventional radiologists that can help in the elimination of the abnormal connections between the arteries and veins.[24] According to "Parkes Weber syndrome—Diagnostic and management paradigms: A systematic review", published in July 2017, embolization alone or in combination with surgical removal of arteriovenous malformations leads to significant clinical improvement.[27] Laser therapy can also help lighten capillary malformations and can speed up the healing process of the bleeding lesions.

Other specialists are needed for dealing with the progression of the disease, such as: physical therapists, occupational therapists and counselors.[24] Physical therapists can help ease the pain and increase the range of movements of the arm or leg that is overgrown. Occupational therapists could help with the development of motor skills impeded by physical problems. The classic port-wine stains may make the patient feel uncomfortable and counselors can help with the psychological and social issues.

Prognosis

PWS is a progressive condition and advances with age. It is dependent on the extent of the disease and overgrowth, condition of the patient's heart, if the blood vessels are responsive to treatment, overall health of the patient, tolerance of medications and treatments. Based on these factors the prognosis is fair to good.[3] The deformity and overgrowth tend to progress with time until epiphyseal closure. A lot of medical attention is needed to correct the blood vessels.

Recent research

According to NIH clinical trials.gov, research on the port-wine stain and its relation to polymorphisms of RASA1 has commenced in November 2010 and expected to end in November 2019.[28] The purpose of the study is to assess how the port-wine stains can lead to complex syndromes such as PWS. Currently there is little knowledge about the epidemiology of the stains and how they progress with the disease. The research is ongoing and the results are yet to be published.

In another review published in July 2017 (discussed in treatments and prognosis), Banzic et al. discussed clinical findings that embolization works really well in patients with PWS. Also, embolization along with surgical resection that targets arteriovenous malformations reliably leads to significant clinical improvements.[27]

See also

References

- ↑ Reference, Genetics Home. "Parkes Weber syndrome". Genetics Home Reference. Archived from the original on 2019-01-21. Retrieved 2019-01-21.

- 1 2 De Wijn, Robert S.; Oduber, Charlène E.U.; Breugem, Corstiaan C.; Alders, Marielle; Hennekam, Raoul C.M.; Van Der Horst, Chantal M.A.M. (2012). "Phenotypic variability in a family with capillary malformations caused by a mutation in the RASA1 gene". European Journal of Medical Genetics. 55 (3): 191–5. doi:10.1016/j.ejmg.2012.01.009. PMID 22342634.

- 1 2 Hartree, Naomi. "Parkes Weber's Syndrome". Archived from the original on 2020-11-26. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- ↑ McKusick, Victor A., MD (1963). "Frederick Parkes Weber—1863-1962". JAMA. 183. doi:10.1001/jama.1963.63700010018015. Archived from the original on 2020-11-26. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Parkes Weber syndrome, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences". Archived from the original on 2020-11-26. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- 1 2 "Parkes Weber syndrome, Genetics Home Reference". Archived from the original on 2019-01-21. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- 1 2 Sunderkrishnan, MD, Ravi (10 November 2019). "Genetics of Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber Syndrome". Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Parkes Weber Syndrome | Symptoms and Causes, Boston Children's Hospital". Archived from the original on 2021-01-21. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- 1 2 3 "Arteriovenous fistula, Mayo Clinic". Archived from the original on 2020-11-26. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "capillary malformation-arteriovenous malformation syndrome, NIH Genetics Home Reference". Archived from the original on 2020-08-10. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Human Phenotype Ontology". Archived from the original on 2021-03-20. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- 1 2 3 Bayrak-Toydemir, Pinar; et al. (1993). "Capillary Malformation-Arteriovenous Malformation Syndrome". RASA1-Related Disorders. University of Washington, Seattle. Archived from the original on 2021-03-03. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- ↑ "Arteriovenous Fistulas: Background, Pathophysiology, Etiology". 14 June 2021. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Cobb, Cynthia (29 November 2017). "Telangiectasia (Spider Veins)". Archived from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ↑ Lee Kulick, Daniel; et al. "Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) Symptoms, Stages, and Prognosis". Archived from the original on 2021-10-19. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- ↑ "Facts About Glaucoma, NIH NEI". Archived from the original on 2016-03-28. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- ↑ Akhtar, M.A.; Campbell, D.J. (2008). "Successful obstetrical management of a woman with Parkes–Weber syndrome". European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 140 (2): 290–1. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2008.03.001. PMID 18439741.

- 1 2 Zhou, Q.; Zheng, J.W. (2009). "Research advances in relationship between RASA1 and vascular anomalies". International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 38 (5): 598. doi:10.1016/j.ijom.2009.03.703.

- ↑ "RASA1 gene RAS p21 protein activator 1". Archived from the original on 2020-08-11. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- 1 2 3 4 "RASA1 RAS p21 protein activator 1". Archived from the original on 2020-11-29. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- ↑ "RASA1 gene RAS p21 protein activator 1". Archived from the original on 2020-08-11. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- ↑ Mneimneh S, Tabaja A, Rajab M (2015). "Klippel-Trenaunay Syndrome with Extensive Lymphangiomas". Case Rep Pediatr. 2015: 581394. doi:10.1155/2015/581394. PMC 4637471. PMID 26587303.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Parkes Weber Syndrome | Conditions + Treatments". Archived from the original on 2021-02-26. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Parkes Weber Syndrome | Treatments". Archived from the original on 2021-01-24. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- ↑ EL-Sobky TA, Elsayed SM, EL Mikkawy DME (2015). "Orthopaedic manifestations of Proteus syndrome in a child with literature update". Bone Rep. 3: 104–108. doi:10.1016/j.bonr.2015.09.004. PMC 5365241. PMID 28377973.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Parkes Weber syndrome, GTR". Archived from the original on 2017-12-14. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- 1 2 Banzic; et al. (2017). "Parkes Weber syndrome-Diagnostic and management paradigms: A systematic review". Phlebology. 32 (6): 371–383. doi:10.1177/0268355516664212. PMID 27511883. S2CID 39980109.

- ↑ "French National Cohort of Children With Port Wine Stain (CONAPE)". 23 February 2017. Archived from the original on 13 December 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

Further reading

- Bayrak-Toydemir, Pinar; Stevenson, David (February 22, 2011). "RASA1-Related Disorders". In Pagon, Roberta A; Adam, Margaret P; Bird, Thomas D; Dolan, Cynthia R; Fong, Chin-To; Stephens, Karen (eds.). GeneReviews™. University of Washington, Seattle. Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved October 4, 2021.

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): PARKES WEBER SYNDROME - 608355

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): TELANGIECTASIA, HEREDITARY BENIGN - 187260

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): TELANGIECTASIA, HEREDITARY HEMORRHAGIC, OF RENDU, OSLER, AND WEBER; HHT - 187300

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): STURGE-WEBER SYNDROME; SWS - 185300

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): KLIPPEL-TRENAUNAY-WEBER SYNDROME - 149000

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): GLOMUVENOUS MALFORMATIONS; GVM - 138000

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): RAS p21 PROTEIN ACTIVATOR 1; RASA1 - 139150

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): CAPILLARY MALFORMATION-ARTERIOVENOUS MALFORMATION - 608354

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|