Rabson–Mendenhall syndrome

| Rabson–Mendenhall syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Pineal hyperplasia, insulin-resistant diabetes mellitus, and somatic abnormalities | |

Rabson–Mendenhall syndrome is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by severe insulin resistance. The disorder is caused by mutations in the insulin receptor gene. Symptoms include growth abnormalities of the head, face and nails, along with the development of acanthosis nigricans. Treatment involves controlling blood glucose levels by using insulin and incorporating a strategically planned, controlled diet. Also, direct actions against other symptoms may be taken (e.g. surgery for facial abnormalities) This syndrome usually affects children and has a prognosis of 1–2 years.

Symptoms and signs

The symptoms of Rabson–Mendenhall syndrome vary from case to case. Major symptoms of Rabson–Mendenhall syndrome include abnormalities of the teeth and nails, such as dental dysplasia, and deformities of the head and face, which include a coarse prematurely-aged facial appearance with a prominent jaw. A skin abnormality known as acanthosis nigricans, which involves a discoloration (hyperpigmentation) and “velvety” thickening (hyperkeratosis) of the skin around skin fold regions of the neck, groin and under arms is also a common symptom.[1] Symptoms will negatively impact the daily life of the patient, and will persist until treated.

Minor symptoms may include an enlargement of the genitalia and precocious puberty and a deficiency or absence of fat tissue. Because individuals with Rabson–Mendenhall syndrome fail to use insulin properly, they may experience abnormally high blood sugar levels (hyperglycemia) after eating a meal, and abnormally low blood sugar levels (hypoglycemia) when not eating.

Mechanism

The condition is transmitted as an autosomal recessive trait, and often affects children of consanguineous parents.[2] The physical findings and symptoms vary greatly among each individual.

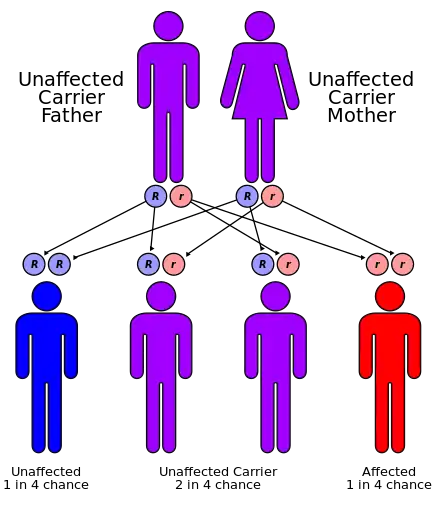

Genetic diseases are determined by two genes, one from the mother and one from the father. Recessive genetic disorders occur when an individual inherits the same abnormal gene for the same trait from each parent. If one of the inherited genes is normal, while the other is for the disease, the person will only be a carrier and will not display any symptoms.[3]

The risk for two carrier parents to both pass the defective gene and, therefore, have an affected child is 25 percent with each pregnancy.[4] The risk to have a child who is a carrier like the parents is 50 percent with each pregnancy. The chance for a child to receive normal genes from both parents and be genetically normal for that particular trait is 25 percent.

Researchers have determined that the Rabson–Mendenhall syndrome is caused by mutations of the insulin receptor gene. The insulin receptor gene is located on the short arm (p) of chromosome 19. Mutations of the insulin-receptor gene lead to an alteration of structure or reduced number of insulin receptors. This results in reduced binding of insulin, and may also lead to abnormalities in the post-receptor pathway. Individuals with Rabson-Mendenall syndrome will need ways to compensate for their insulin resistance, and may do this by increasing insulin secretion. This can lead to excessive insulin levels in the blood (hyperinsulinemia), which can be responsible for multiple symptoms. Definitive genotype–phenotype correlation for insulin receptor defects is difficult to establish primarily due to the rarity of these syndromes.[5] However, researchers believe more severe phenotype changes are due to a mutation in the alpha subunit of the receptor.

Diagnosis

A combination of clinical findings and laboratory tests are used to diagnose Rabson-Mendenhall Syndrome. Initially, individuals are screened for symptoms and have their blood sugar levels analyzed. The two principle tests used to determine insulin resistance are the fasting plasma glucose test (FPG) and the oral glucose tolerance test (GTT). Results from a patient with severe insulin resistance will show values exceeding healthy ranges (≤99 mg/dL for FPG and ≤139 mg/dL for GTT) by over 50 units.[2] A genetic history is also established to determine risk of recurrence in the family. Based on the combination of these findings, an appropriate diagnosis is made.

Rabson–Mendenhall syndrome is commonly associated with Donohue syndrome, also known as "Leprechaunism". Both diseases are autosomal recessive disorders caused by mutations on chromosome 19. Severe insulin resistance and an irregular enlargement of the genitalia are also overlapping symptoms.

Clinical presentation

Rabson and Mendenhall described 3 sibling (2 girls, 1 boy) who initially presented with dental and skin abnormalities, abdominal distention, and phallic enlargement.[6] The children demonstrated early dentition, a coarse, senile-appearing facies, and striking hirsutism. An "adult growth of hair of head" at 5 years of age was pictured in the case of one of the girls. In the older girl the genitalia were large enough at the age of 6 months to permit vaginal examination for diagnosis of a left ovarian tumor which was removed soon afterward. The children were mentally precocious. Prognathism and very thick fingernails as well as acanthosis nigricans were also described. Insulin-resistant diabetes developed, and the patients died during childhood of ketoacidosis and intercurrent infections. At autopsy pineal hyperplasia was found in all three.[6]

Biologically, infants display fasting hypoglycemia, postprandial hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia, which progress to permanent hyperglycemia and recurrent diabetic ketoacidosis.

Treatment

There is no known cure for Rabson–Mendenhall syndrome. However, a series of steps can be directed towards treating the specific symptoms. For example, surgery may be performed to treat dental abnormalities. Furthermore, the goal of the treatment is also to maintain blood glucose levels as constantly as possible. Insulin is not as effective at normal doses, and even large doses show minimal effects. Frequent feeding is the most effective treatment to control blood glucose levels. Well thought out meals with complex combinations of carbohydrates are put together and assigned to the patient in hope of seeing a constant glucose level maintained.[5] Though effective, these treatments tend to show more of an impact initially, and can become ineffective within months.

Treatment of Rabson–Mendenhall syndrome with pharmacologic doses of human leptin may result in improvement of fasting hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, basal glucose, and glucose and insulin tolerance.[7]

Prognosis

Quality of life is impacted severely and the prognosis of patients with Rabson–Mendenhall syndrome remains poor. This is due to the lack of a long-term treatment. Life expectancy is 1–2 years.

Recent research

Recent research has been directed towards finding better treatment options. Multi-drug therapy using insulin sensitizers, such as metformin and pioglitazone, has been linked to improving residual insulin action.[8] High doses of insulin-like growth factor 1 has also been effective in patients with Rabson–Mendenhall syndrome.[9] Though there is no cure, researchers remain optimistic on finding a cure.

References

- ↑ Parveen B; R Sindhuja (2008). "Medical Genetics: Case Report. Rabson-Mendenhall Syndrome". International Journal of Dermatology. 47 (8): 839–841. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03591.x. PMID 18717867. S2CID 5770122.

- 1 2 Semple R; Gorden P; O’Rahilly S; Cochran E; Savage D (2011). "Genetic Syndromes of Severe Insulin Resistance". Endocrine Reviews. 32 (4): 498–514. doi:10.1210/er.2010-0020. PMID 21536711.

- ↑ "Syndromes of Severe Insulin Resistance: Leprechaunism, Rabson-Mendenhall, type a syndromes". Archived from the original on 2020-01-15. Retrieved 2021-05-27.

- ↑ "If a genetic disorder runs in my family, what are the chances that my children will have the condition?". Archived from the original on 2016-01-22. Retrieved 2021-05-27.

- 1 2 Ardon O, Longo N, Mao R, Procter M, Tvrdik T (2014). "Sequencing analysis of insulin receptor defects and detection of two novel mutations in INSR gene". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism Report. 1: 71–84. doi:10.1016/j.ymgmr.2013.12.006. PMC 5121292. PMID 27896077.

- 1 2 Rabson S, Mendenhall E (1956). "Familial hypertrophy of pineal body, hyperplasia of adrenal cortex and diabetes mellitus; report of 3 cases". Am J Clin Pathol. 26 (3): 283–90. doi:10.1093/ajcp/26.3.283. PMID 13302174.

- ↑ Cochran E, Young J, Sebring N, DePaoli A, Oral E, Gorden P (2004). "Efficacy of recombinant methionyl human leptin therapy for the extreme insulin resistance of the Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome". J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 89 (4): 1548–54. doi:10.1210/jc.2003-031952. PMID 15070911.

- ↑ Moreira R, Zagury L, Nascimento T (2010). "Multidrug therapy in a patient with Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome". Diabetologia. 53 (11): 2454–2455. doi:10.1007/s00125-010-1879-5. PMID 20711714. S2CID 41077910.

- ↑ Longo N, Singh R, Griffin LD, Langley SD, Parks JS (2010). "Impaired growth in Rabson-Mendenhall syndrome: lack of effect of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-I". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 79 (3): 799–805. doi:10.1210/jcem.79.3.8077364. PMID 8077364.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|