Chlordiazepoxide

Chlordiazepoxide, trade name Librium among others, is a sedative and hypnotic medication of the benzodiazepine class; it is used to treat anxiety, insomnia and symptoms of withdrawal from alcohol and other drugs.

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌklɔːrdaɪ.əzɪˈpɒksaɪd/ |

| Trade names | Librium, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682078 |

| Routes of administration | By mouth intramuscular |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 5–30 hours (Active metabolite desmethyldiazepam 36–200 hours: other active metabolites include oxazepam) |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.337 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

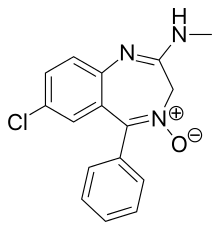

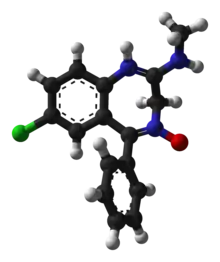

| Formula | C16H14ClN3O |

| Molar mass | 299.76 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Chlordiazepoxide has a medium to long half-life but its active metabolite has a very long half-life. The drug has amnesic, anticonvulsant, anxiolytic, hypnotic, sedative and skeletal muscle relaxant properties.[2]

Chlordiazepoxide was patented in 1958 and approved for medical use in 1960.[3] It was the first benzodiazepine to be synthesized and the discovery of chlordiazepoxide was by pure chance.[4] Chlordiazepoxide and other benzodiazepines were initially accepted with widespread public approval but were followed with widespread public disapproval and recommendations for more restrictive medical guidelines for its use.[5]

Medical uses

Chlordiazepoxide is indicated for the short-term (2–4 weeks) treatment of anxiety that is severe and disabling or subjecting the person to unacceptable distress. It is also indicated as a treatment for the management of acute alcohol withdrawal syndrome.[6]

It can sometimes be prescribed to ease symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome combined with clidinium bromide as a fixed dose medication, Librax.[7]

Contra-indications

Use of chlordiazepoxide should be avoided in individuals with the following conditions:

- Myasthenia gravis

- Acute intoxication with alcohol, narcotics, or other psychoactive substances

- Ataxia

- Severe hypoventilation

- Acute narrow-angle glaucoma

- Severe liver deficiencies (hepatitis and liver cirrhosis decrease elimination by a factor of 2)

- Severe sleep apnea

- Hypersensitivity or allergy to any drug in the benzodiazepine class

Chlordiazepoxide is generally considered an inappropriate benzodiazepine for the elderly due to its long elimination half-life and the risks of accumulation.[8] Benzodiazepines require special precaution if used in the elderly, pregnancy, children, alcohol- or drug-dependent individuals and individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorders.[9]

Pregnancy

The research into the safety of benzodiazepines during pregnancy is limited and it is recommended that use of benzodiazepines during pregnancy should be based on whether the benefits outweigh the risks. If chlordiazepoxide is used during pregnancy the risks can be reduced via using the lowest effective dose and for the shortest time possible. Benzodiazepines should generally be avoided during the first trimester of pregnancy. Chlordiazepoxide and diazepam are considered to be among the safer benzodiazepines to use during pregnancy in comparison to other benzodiazepines. Possible adverse effects from benzodiazepine use during pregnancy include, abortion, malformation, intrauterine growth retardation, functional deficits, carcinogenesis and mutagenesis. Caution is also advised during breast feeding as chlordiazepoxide passes into breast milk.[10][11]

Adverse effects

Sedative drugs and sleeping pills, including chlordiazepoxide, have been associated with an increased risk of death.[12] The studies had many limitations: possibly tending to overestimate risk, such as possible confounding by indication with other risk factors; confusing hypnotics with drugs having other indications;

Common side-effects of chlordiazepoxide include:[13]

- Confusion

- Constipation

- Drowsiness

- Fainting

- Altered sex drive

- Liver problems

- Lack of muscle coordination

- Minor menstrual irregularities

- Nausea

- Skin rash or eruptions

- Swelling due to fluid retention

- Yellow eyes and skin

Chlordiazepoxide in laboratory mice studies impairs latent learning. Benzodiazepines impair learning and memory via their action on benzodiazepine receptors, which causes a dysfunction in the cholinergic neuronal system in mice.[14] It was later found that impairment in learning was caused by an increase in benzodiazepine/GABA activity (and that benzodiazepines were not associated with the cholinergic system).[15] In tests of various benzodiazepine compounds, chlordiazepoxide was found to cause the most profound reduction in the turnover of 5HT (serotonin) in rats. Serotonin is closely involved in regulating mood and may be one of the causes of feelings of depression in rats using chlordiazepoxide or other benzodiazepines.[16]

In September 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) required the boxed warning be updated for all benzodiazepine medicines to describe the risks of abuse, misuse, addiction, physical dependence, and withdrawal reactions consistently across all the medicines in the class.[17]

Tolerance

Chronic use of benzodiazepines, such as chlordiazepoxide, leads to the development of tolerance, with a decrease in number of benzodiazepine binding sites in mice forebrains.[18] The Committee of Review of Medicines, who carried out an extensive review of benzodiazepines including chlordiazepoxide, found—and were in agreement with the US Institute of Medicine and the conclusions of a study carried out by the White House Office of Drug Policy and the US National Institute on Drug Abuse—that there was little evidence that long-term use of benzodiazepines was beneficial in the treatment of insomnia due to the development of tolerance. Benzodiazepines tended to lose their sleep-promoting properties within 3 to 14 days of continuous use, and in the treatment of anxiety the committee found that there was little convincing evidence that benzodiazepines retained efficacy in the treatment of anxiety after four months' continuous use due to the development of tolerance.[19]

Dependence

Chlordiazepoxide can cause physical dependence and what is known as the benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome. Withdrawal from chlordiazepoxide or other benzodiazepines often leads to withdrawal symptoms that are similar to those seen with alcohol and barbiturates. The higher the dose and the longer the drug is taken, the greater the risk of experiencing unpleasant withdrawal symptoms. Withdrawal symptoms can, however, occur at standard dosages and also after short-term use. Benzodiazepine treatment should be discontinued as soon as possible through a slow and gradual dose-reduction regime.[20]

Chlordiazepoxide taken during pregnancy can cause a postnatal benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome.[21]

Overdose

An individual who has consumed excess chlordiazepoxide may display some of the following symptoms:

- Somnolence (difficulty staying awake)

- Mental confusion

- Hypotension

- Hypoventilation

- Impaired motor functions

- Impaired reflexes

- Impaired coordination

- Impaired balance

- Dizziness

- Muscle weakness

- Coma

Chlordiazepoxide is a drug that is very frequently involved in drug intoxication, including overdose.[22] Chlordiazepoxide overdose is considered a medical emergency and, in general, requires the immediate attention of medical personnel. The antidote for an overdose of chlordiazepoxide (or any other benzodiazepine) is flumazenil. Flumazenil should be given with caution as it may precipitate severe withdrawal symptoms in benzodiazepine-dependent individuals.

Pharmacology

Chlordiazepoxide acts on benzodiazepine allosteric sites that are part of the GABAA receptor/ion-channel complex and this results in an increased binding of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA to the GABAA receptor thereby producing inhibitory effects on the central nervous system and body similar to the effects of other benzodiazepines.[23] Chlordiazepoxide is an anticonvulsant.[24]

There is preferential storage of chlordiazepoxide in some organs including the heart of the neonate. Absorption by any administered route and the risk of accumulation is significantly increased in the neonate. The withdrawal of chlordiazepoxide during pregnancy and breast feeding is recommended, as chlordiazepoxide rapidly crosses the placenta and also is excreted in breast milk.[25] Chlordiazepoxide also decreases prolactin release in rats.[26] Benzodiazepines act via micromolar benzodiazepine binding sites as Ca2+ channel blockers and significantly inhibit depolarization-sensitive Calcium uptake in animal nerve terminal preparations.[27] Chlordiazepoxide inhibits acetylcholine release in mouse hippocampal synaptosomes in vivo. This has been found by measuring sodium-dependent high affinity choline uptake in vitro after pretreatment of the mice in vivo with chlordiazepoxide. This may play a role in chlordiazepoxide's anticonvulsant properties.[28]

Pharmacokinetics

Chlordiazepoxide is a long-acting benzodiazepine drug. The half-life of chlordiazepoxide is from 5 to 30 hours but has an active benzodiazepine metabolite, nordiazepam, which has a half-life of 36 to 200 hours.[29] The half-life of chlordiazepoxide increases significantly in the elderly, which may result in prolonged action as well as accumulation of the drug during repeated administration. Delayed body clearance of the long half-life active metabolite also occurs in those over 60 years of age, which further prolongs the effects of the drugs with additional accumulation after repeated dosing.[30]

Despite its name, chlordiazepoxide is not an epoxide.

History

Chlordiazepoxide (initially called methaminodiazepoxide) was the first benzodiazepine to be synthesized in the mid-1950s. The synthesis was derived from work on a class of dyes, quinazolone-3-oxides. It was discovered by accident when in 1957 tests revealed that the compound had hypnotic, anxiolytic, and muscle relaxant effects. "The story of the chemical development of Librium and Valium was told by Sternbach. The serendipity involved in the invention of this class of compounds was matched by the trials and errors of the pharmacologists in the discovery of the tranquilizing activity of the benzodiazepines. The discovery of Librium in 1957 was due largely to the dedicated work and observational ability of a gifted technician, Beryl Kappell. For some seven years she had been screening compounds by simple animal tests for muscle relaxant activity..."[31] Three years later chlordiazepoxide was marketed as a therapeutic benzodiazepine medication under the brand name Librium. Following chlordiazepoxide, in 1963 diazepam hit the market under the brand name Valium—and was followed by many further benzodiazepine compounds over the subsequent years and decades.[32]

In 1959 it was used by over 2,000 physicians and more than 20,000 patients. It was described as "chemically and clinically different from any of the tranquilizers, psychic energizers or other psychotherapeutic drugs now available." During studies, chlordiazepoxide induced muscle relaxation and a quieting effect on laboratory animals like mice, rats, cats, and dogs. Fear and aggression were eliminated in much smaller doses than those necessary to produce hypnosis. Chlordiazepoxide is similar to phenobarbital in its anticonvulsant properties. However, it lacks the hypnotic effects of barbiturates. Animal tests were conducted in the Boston Zoo and the San Diego Zoo. Forty-two hospital patients admitted for acute and chronic alcoholism, and various psychoses and neuroses were treated with chlordiazepoxide. In a majority of the patients, anxiety, tension, and motor excitement were "effectively reduced." The most positive results were observed among alcoholic patients. It was reported that ulcers and dermatologic problems, both of which involved emotional factors, were reduced by chlordiazepoxide.[33]

In 1963, approval for use was given to diazepam (Valium), a "simplified" version of chlordiazepoxide, primarily to counteract anxiety symptoms. Sleep-related problems were treated with nitrazepam (Mogadon), which was introduced in 1972, temazepam (Restoril), which was introduced in 1979, and flurazepam (Dalmane), which was introduced in 1975.[34]

Recreational use

In 1963, Carl F. Essig of the Addiction Research Center of the National Institute of Mental Health stated that meprobamate, glutethimide, ethinamate, ethchlorvynol, methyprylon and chlordiazepoxide were drugs whose usefulness “can hardly be questioned.” However, Essig labeled these “newer products” as “drugs of addiction,” like barbiturates, whose habit-forming qualities were more widely known. He mentioned a 90-day study of chlordiazepoxide, which concluded that the automobile accident rate among 68 users was 10 times higher than normal. Participants' daily dosage ranged from 5 to 100 milligrams.[35]

Chlordiazepoxide is a drug of potential misuse and is frequently detected in urine samples of drug users who have not been prescribed the drug.[36]

Legal status

Internationally, chlordiazepoxide is a Schedule IV controlled drug under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[37]

Toxicity

Animal

Laboratory tests assessing the toxicity of chlordiazepoxide, nitrazepam and diazepam on mice spermatozoa found that chlordiazepoxide produced toxicities in sperm including abnormalities involving both the shape and size of the sperm head. Nitrazepam, however, caused more profound abnormalities than chlordiazepoxide.[38]

Availability

Chlordiazepoxide is available in various dosage forms, alone or in combination with other drugs, worldwide. In combination with Clidinium as NORMAXIN-CC and in combination with dicyclomine as NORMAXIN for IBS, and with the anti-depressant amitriptyline as Limbitrol.[39]

See also

References

- Anvisa (2023-03-31). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-04-04). Archived from the original on 2023-08-03. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- Liljequist R, Palva E, Linnoila M (1979). "Effects on learning and memory of 2-week treatments with chlordiazepoxide lactam, N-desmethyldiazepam, oxazepam and methyloxazepam, alone or in combination with alcohol". International Pharmacopsychiatry. 14 (4): 190–8. doi:10.1159/000468381. PMID 42628.

- Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 535. ISBN 9783527607495.

- Ban TA (2006). "The role of serendipity in drug discovery". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 8 (3): 335–44. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2006.8.3/tban. PMC 3181823. PMID 17117615.

- Marshall KP, Georgievskava Z, Georgievsky I (June 2009). "Social reactions to Valium and Prozac: a cultural lag perspective of drug diffusion and adoption". Research in Social & Administrative Pharmacy. 5 (2): 94–107. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2008.06.005. PMID 19524858.

- "Chlordiazepoxide 10mg Capsules - Summary of Product Characteristics". UK Electronic Medicines Compendium. 19 December 2012. Archived from the original on 23 April 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- "Chlordiazepoxide". MedlinePlus Drug Information. February 15, 2017.

- Liu GG, Christensen DB (2002). "The continuing challenge of inappropriate prescribing in the elderly: an update of the evidence". Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association. 42 (6): 847–57. doi:10.1331/108658002762063682. PMID 12482007.

- Authier N, Balayssac D, Sautereau M, Zangarelli A, Courty P, Somogyi AA, Vennat B, Llorca PM, Eschalier A (November 2009). "Benzodiazepine dependence: focus on withdrawal syndrome". Annales Pharmaceutiques Françaises. 67 (6): 408–13. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2009.07.001. PMID 19900604.

- Iqbal MM, Aneja A, Fremont WP (May 2003). "Effects of chlordiazepoxide (Librium) during pregnancy and lactation". Connecticut Medicine. 67 (5): 259–62. PMID 12802839.

- Iqbal MM, Sobhan T, Ryals T (January 2002). "Effects of commonly used benzodiazepines on the fetus, the neonate, and the nursing infant". Psychiatric Services. 53 (1): 39–49. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.53.1.39. PMID 11773648.

- Kripke DF (February 2016). "Mortality Risk of Hypnotics: Strengths and Limits of Evidence" (PDF). Drug Safety. 39 (2): 93–107. doi:10.1007/s40264-015-0362-0. PMID 26563222. S2CID 7946506.

- drugs. "Chlordiazepoxide patient advice including side-effects". drugs.com. Retrieved April 7, 2008.

- Nabeshima T, Tohyama K, Ichihara K, Kameyama T (November 1990). "Effects of benzodiazepines on passive avoidance response and latent learning in mice: relationship to benzodiazepine receptors and the cholinergic neuronal system". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 255 (2): 789–94. PMID 2173758.

- McNamara RK, Skelton RW (March 1992). "Assessment of a cholinergic contribution to chlordiazepoxide-induced deficits of place learning in the Morris water maze". Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 41 (3): 529–38. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(92)90368-p. PMID 1316618. S2CID 42752576.

- Antkiewicz-Michaluk L, Grabowska M, Baran L, Michaluk J (1975). "Influence of benzodiazepines on turnover of serotonin in cerebral structures in normal and aggressive rats". Archivum Immunologiae et Therapiae Experimentalis. 23 (6): 763–7. PMID 1241268.

- "FDA expands Boxed Warning to improve safe use of benzodiazepine drug". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 23 September 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Crawley JN, Marangos PJ, Stivers J, Goodwin FK (January 1982). "Chronic clonazepam administration induces benzodiazepine receptor subsensitivity". Neuropharmacology. 21 (1): 85–9. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(82)90216-7. PMID 6278355. S2CID 24771398.

- Committee on the Review of Medicines (March 1980). "Systematic review of the benzodiazepines. Guidelines for data sheets on diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, medazepam, clorazepate, lorazepam, oxazepam, temazepam, triazolam, nitrazepam, and flurazepam". British Medical Journal. 280 (6218): 910–2. doi:10.1136/bmj.280.6218.910. PMC 1601049. PMID 7388368.

- MacKinnon GL, Parker WA (1982). "Benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome: a literature review and evaluation". The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 9 (1): 19–33. doi:10.3109/00952998209002608. PMID 6133446.

- Moretti M, Montali S (September 1982). "[Fetal defects caused by the passive consumption of drugs]". La Pediatria Medica e Chirurgica. 4 (5): 481–90. PMID 6985425.

- Zevzikovas A, Kiliuviene G, Ivanauskas L, Dirse V (2002). "[Analysis of benzodiazepine derivative mixture by gas-liquid chromatography]". Medicina. 38 (3): 316–20. PMID 12474705.

- Skerritt JH, Johnston GA (May 1983). "Enhancement of GABA binding by benzodiazepines and related anxiolytics". European Journal of Pharmacology. 89 (3–4): 193–8. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(83)90494-6. PMID 6135616.

- Chweh AY, Swinyard EA, Wolf HH, Kupferberg HJ (February 1985). "Effect of GABA agonists on the neurotoxicity and anticonvulsant activity of benzodiazepines". Life Sciences. 36 (8): 737–44. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(85)90193-6. PMID 2983169.

- Olive G, Dreux C (January 1977). "[Pharmacologic bases of use of benzodiazepines in peréinatal medicine]". Archives Françaises de Pédiatrie. 34 (1): 74–89. PMID 851373.

- Grandison L (1982). "Suppression of prolactin secretion by benzodiazepines in vivo". Neuroendocrinology. 34 (5): 369–73. doi:10.1159/000123330. PMID 6979001.

- Taft WC, DeLorenzo RJ (May 1984). "Micromolar-affinity benzodiazepine receptors regulate voltage-sensitive calcium channels in nerve terminal preparations" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PDF). 81 (10): 3118–22. Bibcode:1984PNAS...81.3118T. doi:10.1073/pnas.81.10.3118. PMC 345232. PMID 6328498.

- Miller JA, Richter JA (January 1985). "Effects of anticonvulsants in vivo on high affinity choline uptake in vitro in mouse hippocampal synaptosomes". British Journal of Pharmacology. 84 (1): 19–25. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1985.tb17368.x. PMC 1987204. PMID 3978310.

- Ashton CH. (April 2007). "Benzodiazepine equivalency table". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved September 23, 2007.

- Vozeh S (November 1981). "[Pharmacokinetic of benzodiazepines in old age]". Schweizerische Medizinische Wochenschrift. 111 (47): 1789–93. PMID 6118950.

- "Pharmacological and clinical-studies on valium: a new psychotherapeutic agent of the benzodiazepine class" (PDF). 1980-11-24. Retrieved 2019-05-23.

- Cooper JR, Bloom FE, Roth RH (January 15, 1996). The Complete Story of the Benzodiazepines (seventh ed.). USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-510399-8. Archived from the original on 2008-03-15. Retrieved 7 Apr 2008.

- The New York Times (28 February 1960). "Help For Mental Ills (Reports on Tests of Synthetic Drug Say The Results are Positive)". The New York Times. USA. p. E9.

- Sternbach LH (June 1972). "The discovery of librium". Agents and Actions. 2 (4): 193–6. doi:10.1007/BF01965860. PMID 4557348. S2CID 26923026.

- The New York Times (30 December 1963). "Warning Is Issued On Tranquilizers". The New York Times. USA. p. 23.

- Garretty DJ, Wolff K, Hay AW, Raistrick D (January 1997). "Benzodiazepine misuse by drug addicts". Annals of Clinical Biochemistry. 34 (Pt 1): 68–73. doi:10.1177/000456329703400110. PMID 9022890. S2CID 42665843.

- Psychotropic Substances. New York: United Nations International Narcotics Control Board. 2016. p. 27. ISBN 978-92-1-048165-6.

- Kar RN, Das RK (1983). "Induction of sperm head abnormalities in mice by three tranquilizers". Cytobios. 36 (141): 45–51. PMID 6132780.

- Drugs.com Drugs.com: International availability of chlordiazepoxide Page accessed April 24, 2015