Clorazepate

Clorazepate, sold under the brand name Tranxene among others, is a benzodiazepine medication. It possesses anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, sedative, hypnotic, and skeletal muscle relaxant properties. Clorazepate is an unusually long-lasting benzodiazepine and serves as a prodrug for the equally long-lasting desmethyldiazepam, which is rapidly produced as an active metabolite. Desmethyldiazepam is responsible for most of the therapeutic effects of clorazepate.[2]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

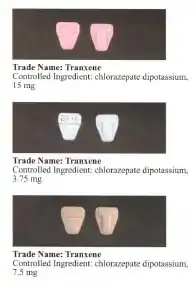

| Trade names | Tranxene, Tranxilium, Novo-Clopate |

| Other names | Clorazepate dipotassium |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682052 |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 91% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 48 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.041.737 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

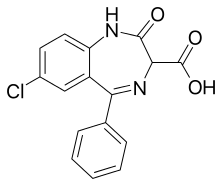

| Formula | C16H11ClN2O3 |

| Molar mass | 314.73 g·mol−1 |

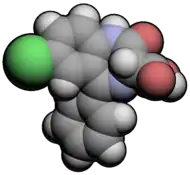

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

It was patented in 1965 and approved for medical use in 1967.[3]

Medical uses

Clorazepate is used in the treatment of anxiety disorders and insomnia. It may also be prescribed as an anticonvulsant or muscle relaxant.[4] It is also used as a premedication.[5]

Clorazepate is prescribed principally in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal and epilepsy, although it is also a useful anxiolytic because of its long half-life. The normal starting dosage range of Clorazepate is 15 to 60 mg per day. The drug is to be taken two to four times per day. Dosages as high as 90 to 120 mg per day may be used in the treatment of acute alcohol withdrawal. In the United States and Canada, Clorazepate is available in 3.75, 7.5, and 15 mg capsules or tablets. In Europe, tablet formations are 5 mg, 10 mg, 20 mg and 50 mg.[6] Clorazepate SD (controlled release) is available and may have a reduced incidence of adverse effects. The sustained-release formulation of clorazepate has some advantages in that, if a dose is missed, less profound fluctuations in blood plasma levels occur, which may be helpful to some people with epilepsy at risk of break-through seizures.[7]

Adverse effects

Adverse effects of clorazepate include tolerance, dependence, withdrawal reactions, cognitive impairment, confusion, anterograde amnesia, falls in the elderly, ataxia, hangover effects, and drowsiness. It is unclear whether cognitive deficits resulting from the long-term use of benzodiazepines return to normal or persist indefinitely after withdrawal from benzodiazepines. Benzodiazepines are also known to cause or worsen depression. Paradoxical effects including excitement and paradoxical worsening of seizures can sometimes result from the use of benzodiazepines. Children, the elderly, individuals with a history of alcohol use disorder or a history of aggressive behavior and anger are at greater risk of developing paradoxical reactions to benzodiazepines.[7]

In September 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) required the boxed warning be updated for all benzodiazepine medicines to describe the risks of non-medical use, addiction, physical dependence, and withdrawal reactions consistently across all the medicines in the class.[8]

Tolerance, dependence and withdrawal

Delirium has been noted from discontinuation from clorazepate.[9] A benzodiazepine dependence occurs in approximately one third of patients who take benzodiazepines for longer than 4 weeks, which is characterised by a withdrawal syndrome upon dose reduction. When used for seizure control, tolerance may manifest itself with an increased rate of seizures as well an increased risk of withdrawal seizures. In humans, tolerance to the anticonvulsant effects of clorazepate occurs frequently with regular use. Due to the development of tolerance, benzodiazepines are, in general, not considered appropriate for the long-term management of epilepsy; increasing the dose may result only in the developing of tolerance to the higher dose combined with worsened adverse effects. Cross-tolerance occurs between benzodiazepines, meaning that, if individuals are tolerant to one benzodiazepine, they will display a tolerance to equivalent doses of other benzodiazepines. Withdrawal symptoms from benzodiazepines include a worsening of pre-existing symptoms as well as the appearance of new symptoms that were not pre-existing. The withdrawal symptoms may range from mild anxiety and insomnia to severe withdrawal symptoms such as seizures and psychosis. Withdrawal symptoms can be difficult in some cases to differentiate between pre-existing symptoms and withdrawal symptoms. Use of high doses, long-term use and abrupt or over-rapid withdrawal increases increase the severity of withdrawal syndrome.[7] However, tolerance to the active metabolite of clorazepate may occur more slowly than with other benzodiazepines.[7] Regular use of benzodiazepines causes the development of dependence characterised by tolerance to the therapeutic effects of benzodiazepines and the development of the benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome including symptoms such as anxiety, apprehension, tremor, insomnia, nausea, and vomiting upon cessation of benzodiazepine use. Withdrawal from benzodiazepines should be gradual as abrupt withdrawal from high doses of benzodiazepines may cause confusion, toxic psychosis, convulsions, or a condition resembling delirium tremens. Abrupt withdrawal from lower doses may cause depression, nervousness, rebound insomnia, irritability, sweating, and diarrhea.[10]

Interactions

All sedatives or hypnotics e.g. other benzodiazepines, barbiturates, antiepileptic drugs, alcohol, antihistamines, opioids, neuroleptics, sleep aids are likely to magnify the effects of clorazepate (and each other) on the central nervous system. Drugs that may interact with clorazepate include, digoxin, disulfiram, fluoxetine, isoniazid, ketoconazole, levodopa, metoprolol, hormonal contraceptives, probenecid, propranolol, rifampin, theophylline, valproic acid.[4] Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, cimetidine, macrolide antibiotics and antimycotics inhibit the metabolism of benzodiazepines and may result in increased plasma levels with resultant enhancement of adverse effects. Phenytoin, phenobarbital, and carbamazepine have the opposite effect, with coadministration leading to increased metabolism and decreased therapeutic effects of clorazepate.[7]

Contraindications and special caution

Benzodiazepines require special precaution if used in the elderly, children, alcohol- or drug-dependent individuals and individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorders.[11]

Clorazepate if used late in pregnancy, the third trimester, causes a definite risk of severe benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome in the neonate with symptoms including hypotonia, and reluctance to suck, to apnoeic spells, cyanosis, and impaired metabolic responses to cold stress. Floppy infant syndrome and sedation in the newborn may also occur. Symptoms of floppy infant syndrome and the neonatal benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome have been reported to persist from hours to months after birth.[12]

Special precaution is required when using clorazepate in the elderly because the elderly metabolise clorazepate more slowly, which may result in excessive drug accumulation. Additionally the elderly are more sensitive to the adverse effects of benzodiazepines compared to younger individuals even when blood plasma levels are the same. Use of benzodiazepines in the elderly is only recommended for 2 weeks and it is also recommended that half of the usual daily dose is prescribed.[7]

Pharmacology

Clorazepate is a "classical" benzodiazepine. Other classical benzodiazepines include chlordiazepoxide, diazepam, clonazepam, oxazepam, lorazepam, nitrazepam, bromazepam and flurazepam.[13] Clorazepate is a long-acting benzodiazepine drug.[10] Clorazepate produces the active metabolite desmethyl-diazepam, which is a partial agonist of the GABAA receptor and has a half life of 20 – 179 hours; a small amount of desmethyldiazepam is further metabolised into oxazepam. Clorazepate exerts its pharmacological properties via increasing the opening frequency of the chloride ion channel of GABAA receptors. This effect of benzodiazepines requires the presence of the neurotransmitter GABA and results in enhanced inhibitory effects of the neurotransmitter GABA acting on GABAA receptors.[7] Clorazepate, like other benzodiazepines, is widely distributed and is highly bound to plasma proteins; clorazepate also crosses readily over the placenta and into breast milk. Peak plasma levels of the active metabolite desmethyl-diazepam are seen between 30 minutes and 2 hours after oral administration of clorazepate. Clorazepate is completely metabolised to desmethyl-diazepam in the gastrointestinal tract and thus the pharmacological properties of clorazepate are largely due to desmethyldiazepam.[7]

Chemistry

Clorazepate is used in the form of a dipotassium salt. It is unusual among benzodiazepines in that it is freely soluble in water.

Clorazepate can be synthesized starting from 2-amino-5-chlorobenzonitrile, which upon reaction with phenylmagnesium bromide is transformed into 2-amino-5-chlorbenzophenone imine.[14][15][16] Reacting this with aminomalonic ester gives a heterocyclization product, 7-chloro-1,3-dihydro-3-carbethoxy-5-phenyl-2H-benzodiazepin-2-one. Upon hydrolysis using an alcoholic solution of potassium hydroxide forms a dipotassium salt, chlorazepate.

Legal status

In the United States, clorazepate is listed under Schedule IV of the Controlled Substances Act.

References

- Anvisa (2023-03-31). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-04-04). Archived from the original on 2023-08-03. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- Ochs HR, Greenblatt DJ, Verburg-Ochs B, Locniskar A (October 1984). "Comparative single-dose kinetics of oxazolam, prazepam, and clorazepate: three precursors of desmethyldiazepam". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 24 (10): 446–451. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1984.tb01817.x. PMID 6150943. S2CID 24414335. Archived from the original on 2009-07-20. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 536. ISBN 9783527607495.

- National Institutes of Health (2003). "Clorazepate". National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 20 May 2008. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- Meybohm P, Hanss R, Bein B, Schaper C, Buttgereit B, Scholz J, Bauer M (September 2007). "[Comparison of premedication regimes. A randomized, controlled trial]". Der Anaesthesist. 56 (9): 890–2, 894–6. doi:10.1007/s00101-007-1208-7. PMID 17551699.

- Tranxene prescribing information in the Netherlands (Dutch language); accessed 2007-03-08.

- Riss J, Cloyd J, Gates J, Collins S (August 2008). "Benzodiazepines in epilepsy: pharmacology and pharmacokinetics" (PDF). Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 118 (2): 69–86. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01004.x. PMID 18384456. S2CID 24453988.

- "FDA expands Boxed Warning to improve safe use of benzodiazepine drug". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 23 September 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Allgulander C, Borg S (June 1978). "Case report: a delirious abstinence syndrome associated with clorazepate (Tranxilen)". The British Journal of Addiction to Alcohol and Other Drugs. 73 (2): 175–177. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1978.tb00139.x. PMID 27202.

- Committee on the Review of Medicines (March 1980). "Systematic review of the benzodiazepines. Guidelines for data sheets on diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, medazepam, clorazepate, lorazepam, oxazepam, temazepam, triazolam, nitrazepam, and flurazepam". British Medical Journal. 280 (6218): 910–912. doi:10.1136/bmj.280.6218.910. PMC 1601049. PMID 7388368.

- Authier N, Balayssac D, Sautereau M, Zangarelli A, Courty P, Somogyi AA, et al. (November 2009). "Benzodiazepine dependence: focus on withdrawal syndrome". Annales Pharmaceutiques Françaises. 67 (6): 408–413. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2009.07.001. PMID 19900604.

- McElhatton PR (Nov 1994). "The effects of benzodiazepine use during pregnancy and lactation". Reproductive Toxicology. 8 (6): 461–475. doi:10.1016/0890-6238(94)90029-9. PMID 7881198.

- Braestrup C, Squires RF (April 1978). "Pharmacological characterization of benzodiazepine receptors in the brain". European Journal of Pharmacology. 48 (3): 263–270. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(78)90085-7. PMID 639854.

- US 3516988, Schmitt J, "1,4 benzodiazepine-2-ones having a carboxylic acid ester or amide group in the 3-position", issued 23 June 1970

- DE 1518764, Schmitt J, "Verfahren zur Herstellung von Orthoaminoarylcetiminen [Process for the preparation of orthoaminoarylcetimins]", published 1971-11-04, assigned to Etablissements Clin-Byla S.A.

- Schmitt J, Comoy P, Suguet M, Calief G, Muer J, Clim T, et al. (1969). "Sur des nouvelles benzodiazepines hydrosolubles douées d'une puissante activité sur le système nerveux central" [On new water-soluble benzodiazepines endowed with a powerful activity on the central nervous system.]. Chim. Ther. (in French). 4: 239.