United States

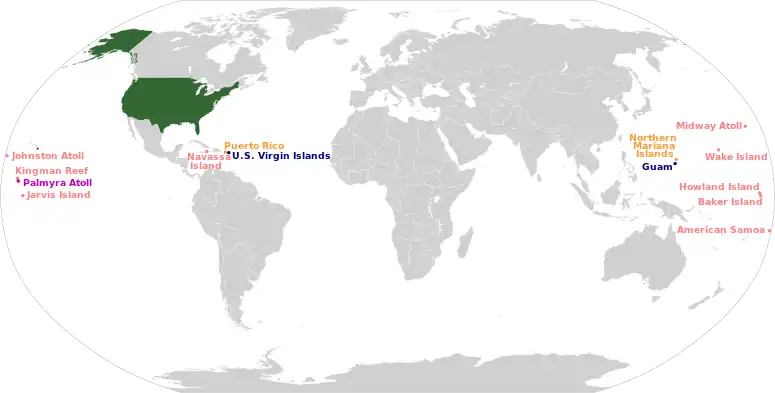

The United States of America (USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S.) or simply America, is a country primarily located in North America and consisting of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territories, and nine Minor Outlying Islands.[lower-alpha 9] It includes 326 Indian reservations. It is the world's third-largest country by both land and total area.[lower-alpha 3] It shares land borders with Canada to its north and with Mexico to its south and has maritime borders with the Bahamas, Cuba, Russia, and other nations.[lower-alpha 10] With a population of over 333 million,[lower-alpha 11] it is the most populous country in the Americas and the third-most populous in the world. The national capital of the United States is Washington, D.C., and its most populous city and principal financial center is New York City.

United States of America | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "In God We Trust"[1] Other traditional mottos:[2]

| |

| Anthem: "The Star-Spangled Banner"[3] | |

| |

| Capital | Washington, D.C. 38°53′N 77°1′W |

| Largest city | New York City 40°43′N 74°0′W |

| Official languages | None at the federal level[lower-alpha 1] |

| National language | English (de facto) |

| Ethnic groups | By race:

By origin:

|

| Religion (2021)[7] |

|

| Demonym(s) | American[lower-alpha 2][8] |

| Government | Federal presidential constitutional republic |

| Joe Biden | |

| Kamala Harris | |

| Mike Johnson | |

| John Roberts | |

| Legislature | Congress |

| Senate | |

| House of Representatives | |

| Independence from Great Britain | |

| July 4, 1776 | |

| March 1, 1781 | |

| September 3, 1783 | |

| June 21, 1788 | |

| May 5, 1992 | |

| Area | |

• Total area | 3,796,742 sq mi (9,833,520 km2)[9] (3rd[lower-alpha 3]) |

• Water (%) | 4.66[10] (2015) |

• Land area | 3,531,905 sq mi (9,147,590 km2) (3rd) |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | |

• 2020 census | 331,449,281[lower-alpha 4][12] (3rd) |

• Density | 87/sq mi (33.6/km2) (185th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2020) | medium |

| HDI (2021) | very high · 21st |

| Currency | U.S. dollar ($) (USD) |

| Time zone | UTC−4 to −12, +10, +11 |

| UTC−4 to −10[lower-alpha 6] | |

| Date format | mm/dd/yyyy[lower-alpha 7] |

| Driving side | right[lower-alpha 8] |

| Calling code | +1 |

| ISO 3166 code | US |

| Internet TLD | .us[16] |

Indigenous peoples have inhabited the Americas for thousands of years. Beginning in 1607, British colonization led to the establishment of the Thirteen Colonies in what is now the Eastern United States. They clashed with the British Crown over taxation and political representation, which led to the American Revolution and the ensuing Revolutionary War. The United States declared independence on July 4, 1776, becoming the first nation-state founded on Enlightenment principles of unalienable natural rights, consent of the governed, and liberal democracy. The country began expanding across North America, spanning the continent by 1848. Sectional division over slavery led to the secession of the Confederate States of America, which fought the remaining states of the Union during the American Civil War (1861–1865). With the Union's victory and preservation, slavery was abolished nationally. By 1900, the United States had established itself as a great power, becoming the world's largest economy. After Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the U.S. entered World War II on the side of the Allies. The aftermath of the war left the United States and the Soviet Union as the world's two superpowers and led to the Cold War, during which both countries engaged in a struggle for ideological dominance and international influence but avoided direct military conflict. They also competed in the Space Race, which culminated in the 1969 landing of Apollo 11, making the U.S. the only nation to land humans on the Moon. With the Soviet Union's collapse and the subsequent end of the Cold War in 1991, the United States emerged as the world's sole superpower.

The United States government is a federal presidential constitutional republic and liberal democracy with three separate branches of government: executive, legislative, and judicial. It has a bicameral national legislature composed of the House of Representatives, a lower house based on population; and the Senate, an upper house based on equal representation for each state. Many policy issues are decentralized at a state or local level, with widely differing laws by jurisdiction which may not conflict with the Constitution.[26][27] The U.S. ranks very highly in international measures of quality of life, income and wealth, economic competitiveness, human rights, innovation, and education; it has low levels of perceived corruption. It has higher levels of incarceration and inequality than most other liberal democracies and is the only liberal democracy without universal healthcare. As a melting pot of cultures and ethnicities, the U.S. has been drastically shaped by the world's largest immigrant population.

Highly developed, the U.S. has the greatest disposable income per capita and by far the largest amount of wealth of any country. The American economy accounts for approximately a quarter of global GDP and is the world's largest by nominal GDP. The U.S. is the world's largest importer and second-largest exporter, as well as the largest consumer market. It is a founding member of the United Nations, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the Organization of American States, NATO, and WHO, and is a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council. It wields considerable global influence as the world's foremost political, cultural, economic, military, and scientific power.

Etymology

The first documentary evidence of the phrase "United States of America" dates back to a letter from January 2, 1776, written by Stephen Moylan, a Continental Army aide to General George Washington, to Joseph Reed, Washington's aide-de-camp. Moylan expressed his desire to go "with full and ample powers from the United States of America to Spain" to seek assistance in the Revolutionary War effort.[28][29][30] The first known publication of the phrase "United States of America" was in an anonymous essay in The Virginia Gazette newspaper in Williamsburg, on April 6, 1776.[31]

By June 1776, the name "United States of America" appeared in drafts of the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, authored by John Dickinson, a Founding Father from the Province of Pennsylvania,[32][33] and in the Declaration of Independence, written primarily by Thomas Jefferson and adopted by the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia, on July 4, 1776.[32]

History

Beginnings (before 1630)

The first inhabitants of North America migrated from Siberia, crossing the Bering land bridge and arriving in the present-day United States at least 12,000 years ago; some evidence suggests an even earlier date of arrival.[34][35][36] The Clovis culture, which appeared around 11,000BC, is believed to represent the first wave of human settlement in the Americas.[37][38] This was likely the first of three major waves of migration into North America; later waves brought the ancestors of present-day Athabaskans, Aleuts, and Eskimos.[39]

Over time, indigenous cultures in North America grew increasingly sophisticated, and some, such as the pre-Columbian Mississippian culture in the southeast, developed advanced agriculture, architecture, and complex societies.[40] The city-state of Cahokia was the largest, most complex pre-Columbian archaeological site in present-day United States.[41] In the Four Corners region in present-day Southwestern United States, the culture of Ancestral Puebloans developed over centuries of agricultural experimentation.[42] The Algonquian, consisting of peoples who speak Algonquian languages, were one of the most populous and widespread North American indigenous peoples.[43] These people were historically prominent along the Atlantic Coast and in the Saint Lawrence River and Great Lakes regions. Before European immigrants made contact, most of the Algonquian relied on hunting and fishing, and many supplemented their diet by cultivating corn, beans, and squash, known as the "Three Sisters". By European contact in the 17th century, they practiced slash and burn agriculture, using controlled fire to extend farmlands' productivity and manage land.[44][45][46][47][48][49] The Ojibwe cultivated wild rice.[50] The Iroquois confederation Haudenosaunee, located in the southern Great Lakes region, was established between the 12th and 15th centuries.[51]

Estimating the native population of North America before the arrival of European immigrants is difficult.[52][53] Estimates range from over 500,000[54][52] to nearly 10 million living near the Gulf of Mexico, Atlantic coast, and Mississippi Valley.[52][53]

The Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano, sent by France to the New World in 1525, encountered Native American inhabitants in the present-day New York Bay region.[55] The Spanish Empire set up their first settlements in Florida and New Mexico, including in Saint Augustine (1565), which is often considered the nation's oldest city,[56] and Santa Fe (1598). The French established their own settlements along the Mississippi River and Gulf of Mexico, including in New Orleans (1718) and Mobile (1702).[57]

Colonization, settlement, and communities (1630–1763)

British colonization of the east coast of North America began with the Virginia Colony in 1607, where Pilgrims settled in Jamestown and later established Plymouth Colony in 1620.[58][59] Many English settlers were dissenting Christians who fled England seeking religious freedom.

The continent's first elected legislative assembly, the House of Burgesses in Virginia, was founded in 1619. In 1636, Harvard College in Cambridge, Massachusetts Bay Colony was founded as the first institution of higher education. The Mayflower Compact and the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut established precedents for representative self-government and constitutionalism that would develop throughout the American colonies.[60][61] The native population of America declined after European arrival,[62][63][64] primarily as a result of infectious diseases such as smallpox and measles.[65][66] By the mid-1670s, the British defeated and seized the territory of Dutch settlers in New Netherland, in the mid-Atlantic region.

During the 17th century European colonization many European settlers experienced food shortages, disease, and conflicts with Native Americans, particularly in King Philip's War. In addition to conflicts with European settlers, Native American polities also warred with each other. But in many cases, the natives and settlers came to develop a mutual dependency. Settlers traded for food and animal pelts, and Native Americans traded for guns, tools, and other European goods.[67] Native Americans taught many settlers to cultivate corn, beans, and other foodstuffs. European missionaries and others felt it was important to "civilize" the Native Americans and urged them to adopt European agricultural practices and lifestyles.[68][69] With the increased European colonization of North America, however, Native Americans were often displaced or killed during conflicts.[70]

European settlers also began trafficking African slaves into the colonial United States via the transatlantic slave trade.[71] By the turn of the 18th century, slavery supplanted indentured servitude as the main source of agricultural labor for the cash crops in the Southern Colonies.[72] Colonial society was divided over the religious and moral implications of slavery, and several colonies passed acts for or against it as well as laws designed to keep Blacks subservient.[73][74]

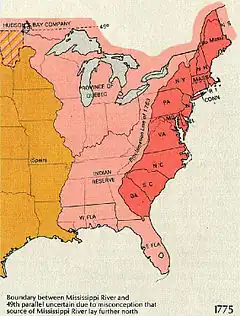

In what was then considered British America, the Thirteen Colonies[lower-alpha 12] were administered as overseas dependencies by the British.[75] All colonies had local governments with elections open to white male property owners except Jews and, in some areas, Catholics.[76][77] With very high birth rates, low death rates, and steadily growing settlements, the colonial population grew rapidly, eclipsing Native American populations.[78] The Christian revivalist movement of the 1730s and 1740s, known as the Great Awakening, fueled colonial interest in both religion and religious liberty.[79] Excluding the Native Americans, the Thirteen Colonies had a population of over 2.1 million in 1770, roughly a third the size of Great Britain. By the 1770s, despite continuing new immigrant arrivals from Britain and other European regions, the natural increase of the population was such that only a small minority of Americans had been born overseas.[80] The colonies' distance from Britain had allowed for the development of self-governance in the colonies, but it encountered periodic efforts by British monarchs to reassert royal authority.[81]

Revolution and the new nation (1763–1789)

%252C_by_John_Trumbull.jpg.webp)

After the British victory in the French and Indian War that was won largely through the support in men and materiel from the colonies, the British began to assert greater control in local colonial affairs, fomenting colonial political resistance. In 1774, to demonstrate colonial dissatisfaction with the lack of representation in the British government that extracted taxes from them, the First Continental Congress met in Philadelphia and passed the Continental Association, which mandated a colonies-wide boycott of British goods. The British attempted to disarm the Americans, resulting in the Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, igniting the American Revolutionary War. The then United Colonies responded by again convening in Philadelphia as the Second Continental Congress where, in June 1775, they appointed George Washington as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, which was initially composed of various American patriot militias resisting the British Army. In June 1776, the Second Continental Congress charged a committee with writing a Declaration of Independence, largely drafted by Thomas Jefferson.[82]

On July 4, 1776, the Second Continental Congress with alterations unanimously adopted and issued the Declaration of Independence, which famously stated: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness." The adoption of the Declaration of Independence is celebrated annually on July 4 in the United States as Independence Day.[83] In 1777, the American victory at the Battle of Saratoga resulted in the capture of a British army, and led to France and their ally Spain joining in the war against them. After the surrender of a second British Army at the siege of Yorktown in 1781, Britain signed a peace treaty. American sovereignty gained international recognition, and the new nation took possession of substantial territory east of the Mississippi River, from what is present-day Canada in the north to Florida in the south.[84] Tensions with Britain remained, leading to the War of 1812, which was fought to a draw.[85]

In 1781, the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union established a decentralized government that operated until 1789.[83] Considered one of the most important legislative acts of the Confederation Congress,[86] Northwest Ordinance (1787) established the precedent by which the national government would be sovereign and expand westward with the admission of new states, rather than with the expansion of existing states and their established sovereignty under the Articles. The prohibition of slavery in the territory had the practical effect of establishing the Ohio River as the geographic divide between slave states and free states from the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River, an extension of the Mason–Dixon line. It also helped set the stage for later federal political conflicts over slavery during the 19th century until the American Civil War.

As it became increasingly apparent that the Confederation was insufficient to govern the new country, nationalists advocated for and led the Philadelphia Convention of 1787, where the United States Constitution was authored and then ratified in state conventions in 1788. The U.S. Constitution is the oldest and longest-standing written and codified national constitution in force today.[87] Going into effect in 1789, it reorganized the government into a federation administered by three branches (executive, judicial, and legislative), on the principle of creating salutary checks and balances. George Washington, who led the Continental Army to victory in the Revolutionary War and then willingly relinquished power, was elected the new nation's first President under the new constitution. The Bill of Rights was adopted in 1791, originally forbidding only federal restriction of personal freedoms and guaranteeing a range of legal protections,[88] portions of the Bill of Rights are now applied to state and local governments by virtue of both state and federal court decisions.[89]

Expansion (1789–1860)

During the colonial period, slavery was legal in the American colonies, and "challenges to its moral legitimacy were rare". However, during the American Revolution, many began to question the practice.[90] Regional divisions over slavery grew in the ensuing decades, with prominent Founding Fathers in the northern United States advocating for the abolition of slavery. By the 1810s, slavery had been abolished in all Northern states.[91] Despite the federal government outlawing American participation in the Atlantic slave trade in 1807, the exponential increase in profits for southern elites resulting from the drastic reduction of cotton production costs after the invention of the cotton gin, spurred entrenchment and support of slavery in the southern United States.[92][93][94]

In the late 18th century, American settlers began to expand further westward, some of them with a sense of manifest destiny.[95]The Louisiana Purchase (1803) nearly doubled the acreage of the United States, effectively ending French colonial interest in North America and their opposition to American westward expansion.[96] Spain ceded Florida and other Gulf Coast territory in 1819,[97] The Second Great Awakening, especially in the period 1800–1840, converted millions to evangelical Protestantism. In the North, it energized multiple social reform movements, including abolitionism;[98] in the South, Methodists and Baptists proselytized among slave populations.[99] In 1820, the Missouri Compromise admitted Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state, and instituted a policy of prohibiting slavery in the remaining Louisiana Purchase lands north of the 36°30′ parallel. The outcome de facto sectionalized the country into two factions: free states, which forbade slavery; and slave states, which protected the institution; it was controversial and widely seen as dividing the country along sectarian lines.[100] [101]

As Americans expanded further into land inhabited by Native Americans, the federal government often applied policies of Indian removal or assimilation.[102][103] The displacement prompted a long series of American Indian Wars west of the Mississippi River[104] and eventually conflict with Mexico. Most of these conflicts ended with the cession of Native American territory and their confinement to Indian reservations.[105] The Republic of Texas was annexed in 1845 during a period of expansionism,[101] and the 1846 Oregon Treaty with Britain led to U.S. control of the present-day American Northwest.[106] Victory in the Mexican–American War resulted in the 1848 Mexican Cession of California and much of the present-day American Southwest, resulting in the U.S. spanning the continent from the Atlantic to the Pacific oceans.[95][107]

Civil War and Reconstruction (1860–1876)

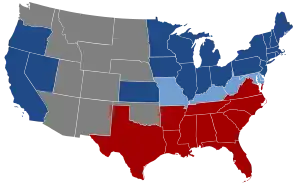

Sectional conflict regarding African slavery[108] was the primary cause of the American Civil War.[109] With the 1860 election of Abraham Lincoln, conventions in eleven slave states in the Southern U.S. declared secession and formed the Confederate States of America, while the remaining states, known as the Union, maintained that secession was unconstitutional and illegitimate.[110] On April 12, 1861, the Confederacy initiated military conflict by bombarding Fort Sumter, a federal garrison in Charleston harbor in South Carolina. The ensuing American Civil War fought between 1861 and 1865 became the deadliest military conflict in American history. The war resulted in the deaths of approximately 620,000 soldiers from both sides and upwards of 50,000 civilians, most of them in the South.[111] In early July 1863, the Civil War began to turn in the Union's favor following the Union Army under General Ulysses S. Grant successfully splitting the Confederacy in two by capturing Vicksburg in the west, denying it any further movement along or across the Mississippi River and preventing supplies from Texas and Arkansas that might sustain the war effort from passing east, almost simultaneous with victory in the Battle of Gettysburg, where Union Army general George Meade halted Confederate Army general Robert E. Lee's invasion of the North. In April 1865, following the Union Army's victory at the Battle of Appomattox Court House, the Confederacy surrendered and soon collapsed.[112]

Reconstruction began in earnest following the defeat of the Confederates. While President Lincoln attempted to foster reconciliation between the Union and former Confederacy, his assassination on April 14, 1865 drove a wedge between North and South again. "Radical Republicans" in the federal government made it their goal to oversee the rebuilding of the South and to ensure the rights of African Americans, and the so-called Reconstruction Amendments to the Constitution guaranteed the abolishment of slavery, full citizenship to Americans of African descent, and suffrage for adult Black men. They persisted until the Compromise of 1877.[113]

To encourage additional westward settlement the Homestead Acts were several laws in the United States by which an applicant could acquire ownership of government land or the public domain, typically called a "homestead". In all, more than 160 million acres (650 thousand km2; 250 thousand sq mi) of public land, or nearly 10 percent of the total area of the United States, was given away free to 1.6 million homesteaders; most of the homesteads were west of the Mississippi River. The Southern Homestead Act of 1866 was enacted specifically to break a cycle of debt during Reconstruction. Prior to this act, blacks and impoverished whites alike were having trouble buying land or did not have the means to travel west. Sharecropping and tenant farming had become ways of life. This act attempted to solve this by selling land at low prices so marginalized Southerners could buy it. Many, however, could still not participate because the low prices remained out of reach.[114]

Development of the modern United States (1876–1914)

Influential Southern Whites, calling themselves "Redeemers",[115] took local control of the South after the end of Reconstruction, leading to the nadir of American race relations. From 1890 to 1910, the Redeemers established so-called Jim Crow laws, disenfranchising almost all Blacks and some impoverished Whites throughout the region. Blacks faced racial segregation nationwide and codified discrimination, especially in the South,[116] and lived under the threat of lynching and other vigilante violence.[117][118]

National infrastructure, including telegraph and transcontinental railroads, spurred economic growth and greater settlement and development of the American Old West. After the end of the American Civil War in 1865, new transcontinental railways made relocation easier for settlers, expanded internal trade, and increased conflicts with Native Americans.[119] Mainland expansion also included the purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867.[120] In 1893, pro-American elements in Hawaii overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy and formed the Republic of Hawaii, which the U.S. annexed in 1898. Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines were ceded by Spain in the same year, by the Treaty of Paris (1898) following the Spanish–American War.[121] Puerto Ricans did not gain citizenship either through the Foraker Act (1900) or the Insular Cases (1901), but through the Jones–Shafroth Act in 1917,[122]: 60–63 allowing for the conscription of 20,000 Puerto Ricans, which began two months later.[123] American Samoa was acquired by the United States in 1900 after the end of the Second Samoan Civil War.[124] The U.S. Virgin Islands were purchased from Denmark in 1917.[125]

From 1865 through 1918 an unprecedented and diverse stream of immigrants arrived in the United States, 27.5 million in total. Of those, 24.4 million (89%) came from Europe, including from Great Britain, Ireland, Scandinavia, Germany, Italy, Russia and other parts of Central and Eastern Europe. Another 1.7 million came from Canada.[128] Most came through the port of New York City, and from 1892 specifically through the now iconic immigration station on Ellis Island there, but some ethnic groups tended to congregate in specific locations. New York and other large cities of the East Coast became home to large Jewish, Irish, and Italian populations, while many Germans and Central Europeans moved to the Midwest, obtaining jobs in industry and mining. At the same time, about one million French Canadians migrated from Quebec to New England.[129] The Great Migration, which began around 1910, resulted in millions of African Americans leaving the rural South for urban areas in the North.[130]

Rapid economic development during the late 19th and early 20th centuries fostered the rise of many prominent industrialists, largely by their formation of trusts and monoplies to prevent competition.[131] Tycoons like Cornelius Vanderbilt, John D. Rockefeller, and Andrew Carnegie led the nation's expansion in the railroad, petroleum, and steel industries. Banking became a major part of the economy, with J. P. Morgan playing a notable role. The United States also emerged as a pioneer of the automotive industry in the early 20th century.[132] These changes were accompanied by significant increases in economic inequality, slum conditions, and social unrest, which prompted the rise of populist, socialist, and anarchist movements.[133][134][135] This period eventually ended with the advent of the Progressive Era, which was characterized by significant reforms, including health and safety regulation of consumer goods, the rise of labor unions, greater antitrust measures to ensure competition among businesses, and improvements in worker conditions.[136]

World Wars period (1914–1945)

The United States remained neutral after the outbreak of World War I in 1914 until 1917 when it joined the war as an "associated power" alongside the Allies of World War I, helping to turn the tide against the Central Powers, and played a leading role in the Paris Peace Conference.[137] In 1920, a constitutional amendment granted nationwide women's suffrage.[138] During the 1920s and 1930s, radio for mass communication and ultimately the invention of early television transformed communications in the United States.[139] The prosperity of the Roaring Twenties ended with the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the onset of the Great Depression. After his election as president in 1932, Franklin D. Roosevelt, between 1933 and 1939, introduced his New Deal social and economic policies, which included public works projects, financial reforms, and regulations which represented a shift to a new current of modern liberalism in the United States".[140] The Dust Bowl of the mid-1930s impoverished many farming communities and spurred a new wave of western migration.[141]

At first neutral during World War II, the U.S. began supplying war materiel to the Allies of World War II in March 1941. On December 7, 1941, the Empire of Japan launched a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, causing the U.S. to militarily join the Allies against the Axis powers.[142][143] The U.S. pursued a "Europe first" defense policy, and the Philippines was invaded and occupied by Japan until its liberation by U.S. led forces in 1944–1945. The U.S. developed the first nuclear weapons and used them againast the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945; the subsequent surrender of Japan on September 2 ended World War II.[144][145] The United States was one of the "Four Policemen" who met to plan the postwar world, alongside the United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and China.[146][147] It played a leading role in the Bretton Woods and Yalta conferences, and participated in a 1945 international conference that produced the United Nations Charter, which became active after the war's end.[148] The U.S. emerged relatively unscathed from the war, with even greater economic and military influence.[149]

Contemporary United States (1945–present)

After World War II, the United States launched the Marshall Plan to aid in the reconstruction of Europe.[150] This period also marked the beginning of the Cold War, where geopolitical tensions between the U.S. and the Soviet Union driven by ideological differences led the two countries to dominate the military affairs of Europe,[151] with the U.S.-led capitalist Western Bloc opposing the Soviet-led communist Eastern Bloc. The U.S. engaged in regime change against governments perceived to be aligned with the Soviet Union, participated in conflicts like the Korean and Vietnam Wars, and competed in the Space Race, culminating in the first crewed Moon landing in 1969.[152][153][154][155][156] Domestically, the U.S. experienced large economic growth, urbanization, and population growth following World War II,[157] and admitted Alaska and Hawaii as states.[158]

.jpg.webp)

The civil rights movement emerged, with Martin Luther King Jr. becoming a prominent leader in the early 1960s.[159] President Lyndon B. Johnson initiated the "Great Society", introducing sweeping legislation and policies to address poverty and racial inequalities.[160] The counterculture movement in the U.S. brought significant social changes, including the liberalization of attitudes towards what substances are acceptable for recreational drug use, sexuality[161][162] and the beginning of the modern gay rights movement as well as open defiance of the military draft and opposition to intervention in Vietnam.[163] The presidency of Richard Nixon saw the American withdrawal from Vietnam but also the Watergate scandal, which led to his resignation and a decline in public trust of government that expanded for decades.[164] After a surge in female labor participation around the 1970s, by 1985, the majority of women aged 16 and over were employed.[165] The 1970s and early 1980s saw economic stagflation and President Ronald Reagan responded with neoliberal reforms and a rollback strategy towards the Soviet Union.[166][167][168][169] The late 1980s and early 1990s saw the collapse of the Warsaw Pact and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, which marked the end of the Cold War and solidified the U.S. as the world's sole superpower.[170][171][172][173]

_-_B6019~11.jpg.webp)

In the first decades of the 21st century, the U.S. faced challenges from terrorism, with the September 11 attacks in 2001 leading to the war on terror and military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq.[174][175] The U.S. housing bubble in 2006 culminated in the 2007–2008 financial crisis and the Great Recession, the largest economic contraction since the Great Depression.[176] Amid the financial crisis, Barack Obama, the first multiracial president, was elected in 2008.[177][178] Political polarization increased as sociopolitical debates on cultural issues dominated political discussion.[179] The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in over 100 million confirmed cases and 1 million deaths,[180] making it the most deadly pandemic in U.S. history.[181] Attempts to overturn the 2020 U.S. presidential election culminated in the January 6, 2021 attack on the United States Capitol that attempted to prevent the peaceful transition of power to president-elect Joe Biden.[182]

Geography

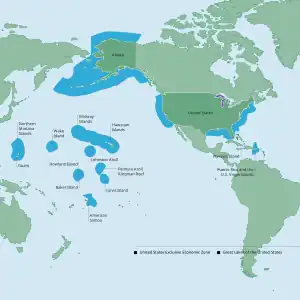

The 48 contiguous states and the District of Columbia occupy a combined area of 3,119,885 square miles (8,080,470 km2). Of this area, 2,959,064 square miles (7,663,940 km2) is contiguous land, composing 83.65% of total U.S. land area.[183][184] About 15% is occupied by Alaska, a state in northwestern North America, with the remainder in Hawaii, a state and archipelago in the central Pacific, and the five populated but unincorporated insular territories of Puerto Rico, American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.[185] Measured by only land area, the United States is third in size behind Russia and China, and just ahead of Canada.[186] The United States is the world's third-largest nation by land and total area behind Russia and Canada.[lower-alpha 3][187]

The coastal plain of the Atlantic seaboard gives way further inland to deciduous forests and the rolling hills of the Piedmont.[188] The Appalachian Mountains and the Adirondack massif divide the eastern seaboard from the Great Lakes and the grasslands of the Midwest.[189] The Mississippi–Missouri River, the world's fourth longest river system, runs mainly north–south through the heart of the country. The flat, fertile prairie of the Great Plains stretches to the west, interrupted by a highland region in the southeast.[189]

The Rocky Mountains, west of the Great Plains, extend north to south across the country, peaking at over 14,000 feet (4,300 m) in Colorado.[190] Farther west are the rocky Great Basin and deserts such as the Chihuahua, Sonoran, and Mojave.[191] The Sierra Nevada and Cascade mountain ranges run close to the Pacific coast, both ranges also reaching altitudes higher than 14,000 feet (4,300 m). The lowest and highest points in the contiguous United States are in the state of California,[192] and only about 84 miles (135 km) apart.[193] At an elevation of 20,310 feet (6,190.5 m), Alaska's Denali is the highest peak in the country and in North America.[194] Active volcanoes are common throughout Alaska's Alexander and Aleutian Islands, and Hawaii consists of volcanic islands. The supervolcano underlying Yellowstone National Park in the Rockies is the continent's largest volcanic feature.[195]

Climate

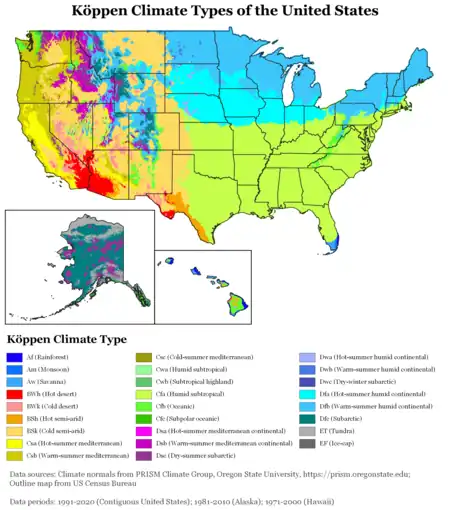

With its large size and geographic variety, the United States includes most climate types. To the east of the 100th meridian, the climate ranges from humid continental in the north to humid subtropical in the south.[196]

The Great Plains west of the 100th meridian are semi-arid. Many mountainous areas of the American West have an alpine climate. The climate is arid in the Great Basin, desert in the Southwest, Mediterranean in coastal California, and oceanic in coastal Oregon and Washington and southern Alaska. Most of Alaska is subarctic or polar. Hawaii and the southern tip of Florida are tropical, as well as its territories in the Caribbean and the Pacific.[197]

States bordering the Gulf of Mexico are prone to hurricanes, and most of the world's tornadoes occur in the country, mainly in Tornado Alley areas in the Midwest and South.[198] Overall, the United States receives more high-impact extreme weather incidents than any other country in the world.[199]

Extreme weather became more frequent in the U.S. in the 21st century, with three times the number of reported heat waves as in the 1960s. Of the ten warmest years ever recorded in the 48 contiguous states, eight occurred after 1998. In the American Southwest, droughts became more persistent and more severe.[200]

Biodiversity and conservation

.jpg.webp)

The U.S. is one of 17 megadiverse countries containing large numbers of endemic species: about 17,000 species of vascular plants occur in the contiguous United States and Alaska, and more than 1800 species of flowering plants are found in Hawaii, few of which occur on the mainland.[202] The United States is home to 428 mammal species, 784 birds, 311 reptiles, and 295 amphibians,[203] and 91,000 insect species.[204]

There are 63 national parks, and hundreds of other federally managed parks, forests, and wilderness areas, managed by the National Park Service and other agencies.[205] Altogether, about 28% of the country's land area is publicly owned and federally managed,[206] primarily located in the western states.[207] Most of this land is protected, though some is leased for oil and gas drilling, mining, logging, or cattle ranching, and less than one percent of it is used for military purposes.[208][209]

Environmental issues in the United States include debates on non-renewable resources and nuclear energy, air and water pollution, biological diversity, logging and deforestation,[210][211] and climate change.[212][213] The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), created by presidential order in 1970, is the federal agency charged with enforcing and addressing most environmental-related issues.[214] The idea of wilderness has shaped the management of public lands since 1964, with the Wilderness Act.[215] The Endangered Species Act of 1973 is intended to protect threatened and endangered species and their habitats, which are monitored by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service.[216]

As of 2020, the U.S. ranked 24th among 180 nations in the Environmental Performance Index.[217] The country joined the Paris Agreement on climate change in 2016, and has many other environmental commitments.[218] It withdrew from the Paris Agreement in 2020[219] but rejoined it in 2021.[220]

Government and politics

.jpg.webp)

The United States was founded on the principles of the American Enlightenment. It is a federal republic of 50 states, a federal district, five territories and several uninhabited island possessions.[221][222][223] It is the world's oldest surviving federation, and, according to the World Economic Forum, the oldest democracy as well.[224] It is a liberal representative democracy "in which majority rule is tempered by minority rights protected by law."[225]

The U.S. Constitution serves as the country's supreme legal document, establishing the structure and responsibilities of the federal government and its relationship with the individual states. The Constitution has been amended 27 times.[226]

The federal government comprises three branches, which are headquartered in Washington, D.C. and regulated by a system of checks and balances defined by the Constitution.[227]

- The U.S. Congress, a bicameral legislature, made up of the Senate and the House of Representatives, makes federal law, declares war, approves treaties, has the power of the purse,[228] and has the power of impeachment, by which it can remove the President, Vice President, and presidentially-appointed civil Officers of the United States.[229] Each chamber determines the method of trial and punishment for its own members, and may expel a member with a two-thirds majority[230] The Senate has 100 members, elected for a six-year term in dual-seat constituencies (2 from each state), with one-third being renewed every two years. The House of Representatives has 435 members, elected for a two-year term in single-seat constituencies of approximately equal population, and elections occur every two years, correlated with presidential elections or halfway through a president's term.

- The U.S. President is the commander-in-chief of the military, can veto legislative bills before they become law (subject to congressional override), and appoints the members of the Cabinet (subject to Senate approval) and other officers, who administer and enforce federal laws and policies through their respective agencies.[231] The president and the vice president are elected together in a presidential election.[232] It is an indirect election, with the winner being determined by votes cast by electors of the Electoral College. In modern times, voters in each state select a slate of electors from a list of several slates designated by different parties or candidates, and the electors typically promise in advance to vote for the candidates of their party (whose names of the presidential candidates usually appear on the ballot rather than those of the individual electors). The winner of the election is the candidate with at least 270 Electoral College votes. The President and Vice President serve a four-year term and may be elected to the office no more than twice.

- The U.S. federal judiciary, whose judges are all appointed for life by the President with Senate approval, consists primarily of the U.S. Supreme Court, the U.S. Courts of Appeals, and the U.S. District Courts. The U.S. Supreme Court interprets laws and overturn those they find unconstitutional.[233] The Supreme Court is led by the chief justice of the United States. It has nine members who serve for life. The members are appointed by the sitting president when a vacancy becomes available.[234] Federal judges, like Supreme Court justices, are appointed by the president with the consent of the Senate to serve until they resign, are impeached and convicted, retire, or are deceased.

Political subdivisions

In the American federal system, sovereignty is shared between two levels of government: federal and state. Each of the 50 states has territory where it shares sovereignty with the federal government. States are subdivided into counties or county equivalents, and further divided into municipalities. The District of Columbia is a federal district that contains the capital of the United States, the city of Washington.[235] People in the states are also represented by local elected governments, which are administrative divisions of the states. The territories and the District of Columbia are administrative divisions of the federal government. Governance on many issues is decentralized.[236]

Foreign relations

.jpg.webp)

The United States has an established structure of foreign relations, and it had the world's second-largest diplomatic corps in 2019.[237] It is a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council,[238] and home to the United Nations headquarters.[239] The United States is also a member of the G7,[240] G20,[241] and OECD intergovernmental organizations.[242] Almost all countries have embassies and many have consulates (official representatives) in the country. Likewise, nearly all nations host formal diplomatic missions with the United States, except Iran,[243] North Korea,[244] and Bhutan.[245] Though Taiwan does not have formal diplomatic relations with the U.S., it maintains close unofficial relations.[246] The United States also regularly supplies Taiwan with military equipment to deter potential Chinese aggression.[247]

The United States has a "Special Relationship" with the United Kingdom[248] and strong ties with Canada,[249] Australia,[250] New Zealand,[251] the Philippines,[252] Japan,[253] South Korea,[254] Israel,[255] and several European Union countries (France, Italy, Germany, Spain, and Poland).[256] The U.S. works closely with its 30NATO allies on military and national security issues, and with nations in the Americas through the Organization of American States and the United States–Mexico–Canada Free Trade Agreement. In South America, Colombia is traditionally considered to be the closest ally of the United States.[257] The U.S. exercises full international defense authority and responsibility for Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, and Palau through the Compact of Free Association.[258] It has increasingly conducted strategic cooperation with India,[259] and its ties with China have steadily deteriorated.[260][261] Since 2014, the U.S. has become a key ally of Ukraine.[262][263]

Military

.jpg.webp)

The President is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces and appoints its leaders, the secretary of defense and the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The Department of Defense, which is headquartered at the Pentagon near Washington, D.C., administers five of the six service branches, which are made up of the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, and Space Force. The Coast Guard is administered by the Department of Homeland Security in peacetime and can be transferred to the Department of the Navy in wartime.[264] The United States spent $877 billion on its military in 2022, which is by far the largest amount of any country, making up 39% of global military spending and accounting for 3.5% of the country's GDP.[265][266] The U.S. has more than 40% of the world's nuclear weapons, the second-largest amount after Russia.[267] The United States has the third-largest combined armed forces in the world, behind the Chinese People's Liberation Army and Indian Armed Forces.[268]

Today, American forces can be rapidly deployed by the Air Force's large fleet of transport aircraft, the Navy's 11 active aircraft carriers, and Marine expeditionary units at sea with the Navy, and Army's XVIII Airborne Corps and 75th Ranger Regiment deployed by Air Force transport aircraft. The Air Force can strike targets across the globe through its fleet of strategic bombers, maintains the air defense across the United States, and provides close air support to Army and Marine Corps ground forces.[269][270]

Law enforcement and crime

There are about 18,000 U.S. police agencies from local to federal level in the United States.[271] Law in the United States is mainly enforced by local police departments and sheriff departments in their municipal or county jurisdictions. The state police departments have authority in their respective state, and federal agencies such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the U.S. Marshals Service have national jurisdiction and specialized duties, such as protecting civil rights, national security and enforcing U.S. federal courts' rulings and federal laws.[272] State courts conduct most civil and criminal trials,[273] and federal courts handle designated crimes and appeals of state court decisions.[274]

As of 2020, the United States has an intentional homicide rate of 7 per 100,000 people.[275] A cross-sectional analysis of the World Health Organization Mortality Database from 2010 showed that United States homicide rates "were 7.0 times higher than in other high-income countries, driven by a gun homicide rate that was 25.2 times higher."[276]

As of January 2023, the United States has the sixth highest per-capita incarceration rate in the world, at 531 people per 100,000; and the largest prison and jail population in the world at 1767200.[277][278] In 2019, the total prison population for those sentenced to more than a year was 1,430,000, corresponding to a ratio of 419 per 100,000 residents and the lowest since 1995.[279] Some think tanks place that number higher, such as Prison Policy Initiative's estimate of 1.9 million.[280] Various states have attempted to reduce their prison populations via government policies and grassroots initiatives.[281]

Economy

According to the International Monetary Fund, the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) is $25.5 trillion, the largest of any country in the world, constituting over 25% of the gross world product at market exchange rates and over 15% of the gross world product at purchasing power parity (PPP).[284][13] From 1983 to 2008, U.S. real compounded annual GDP growth was 3.3%, compared to a 2.3% weighted average for the rest of the Group of Seven.[285] The country ranks first in the world by disposable income per capita, nominal GDP,[286] second by GDP (PPP),[13] seventh by nominal GDP per capita,[284] and eighth by GDP (PPP) per capita.[13]

The U.S. has been the world's largest economy since at least 1900.[287] Anchored by Wall Street in Lower Manhattan, the U.S. is the world's leading financial and fintech center.[288] Many of the world's largest companies, such as Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Apple, AT&T, Coca-Cola, Disney, General Motors, McDonald's, Meta, Microsoft, Nike, Pepsi, and Walmart, were founded and are headquartered in the United States.[289] Of the world's 500 largest companies, 136 are headquartered in the U.S.[289] The U.S. dollar is the currency most used in international transactions and is the world's foremost reserve currency, backed by the country's dominant economy, its military, the petrodollar system, and its linked eurodollar and large U.S. treasuries market.[282] Several countries use it as their official currency and in others it is the de facto currency.[290][291] It has free trade agreements with several countries, including the USMCA.[292] The U.S. ranked second in the Global Competitiveness Report in 2019, after Singapore.[293]

New York City is the world's principal financial center, with the largest economic output, and the epicenter of the principal American metropolitan economy.[294][295][296] The New York Stock Exchange and Nasdaq, both located in New York City, are the world's two largest stock exchanges by market capitalization and trade volume.[297][298] The United States is at or near the forefront of technological advancement and innovation[299] in many economic fields, especially in artificial intelligence; computers; pharmaceuticals; and medical, aerospace and military equipment.[300] The nation's economy is fueled by abundant natural resources, a well-developed infrastructure, and high productivity.[301] It has the second-highest total-estimated value of natural resources. The largest U.S. trading partners are the European Union, Mexico, Canada, China, Japan, South Korea, the United Kingdom, Vietnam, India, and Taiwan.[302] The United States is the world's largest importer and the second-largest exporter after China.[303] It is by far the world's largest exporter of services.[304]

While its economy has reached a post-industrial level of development, the United States remains an industrial power.[306] As of 2018, the U.S. is the second-largest manufacturing nation after China.[307] In 2021, the U.S. was both the world's largest exporter and importer of engines.[308] Despite the fact that the U.S. only accounted for 4.24% of the global population, residents of the U.S. collectively possessed 31.5% of the world's total wealth as of 2021, the largest percentage of any country.[309] The U.S. also ranks first in the number of dollar billionaires and millionaires, with 724 billionaires[310] and nearly 22 million millionaires (as of 2021).[311]

Americans have the highest average household and employee income among OECD member states,[312] and the fourth-highest median household income,[313] up from sixth-highest in 2013.[314] Wealth in the United States is highly concentrated; the richest 10% of the adult population own 72% of the country's household wealth, while the bottom 50% own just 2%.[315] Income inequality in the U.S. remains at record highs,[316] with the top fifth of earners taking home more than half of all income[317] and giving the U.S. one of the widest income distributions among OECD members.[318] There were about 582,500 sheltered and unsheltered homeless persons in the U.S. in 2022, with 60% staying in an emergency shelter or transitional housing program.[319] In 2018 six million children experience food insecurity.[320] Feeding America estimates that around one in seven, or approximately 11 million, children experience hunger and do not know where they will get their next meal or when.[321] As of June 2018, 40 million people, roughly 12.7% of the U.S. population, were living in poverty, including 13.3 million children.[322]

The United States has a smaller welfare state and redistributes less income through government action than most other high-income countries.[323][324] It is the only advanced economy that does not guarantee its workers paid vacation nationally[325] and is one of a few countries in the world without federal paid family leave as a legal right.[326] The United States also has a higher percentage of low-income workers than almost any other developed nation, largely because of a weak collective bargaining system and lack of government support for at-risk workers.[327]

Science, technology, and energy

The United States has been a leader in technological innovation since the late 19th century and scientific research since the mid-20th century. Methods for producing interchangeable parts and the establishment of a machine tool industry enabled the U.S. to have large-scale manufacturing of sewing machines, bicycles, and other items in the late 19th century. In the early 20th century, factory electrification, the introduction of the assembly line, and other labor-saving techniques created the system of mass production.[328] In the 21st century, approximately two-thirds of research and development funding comes from the private sector.[329] In 2022, the United States was the country with the second-highest number of published scientific papers.[330] As of 2021, the U.S. ranked second by the number of patent applications, and third by trademark and industrial design applications.[331] The U.S. had 2,944 active satellites in space in December 2021, the highest number of any country.[332] In 2022, the United States ranked 3rd in the Global Innovation Index.[333]

As of 2021, the United States receives approximately 79.1% of its energy from fossil fuels.[334] In 2021, the largest source of the country's energy came from petroleum (36.1%), followed by natural gas (32.2%), coal (10.8%), renewable sources (12.5%), and nuclear power (8.4%).[334] The United States constitutes less than 5% of the world's population, but consumes 17% of the world's energy.[335] It accounts for about 20% of both the world's annual petroleum consumption and petroleum supply.[336] The U.S. ranks as second-highest emitter of greenhouse gases, exceeded only by China.[337]

Transportation

.jpg.webp)

The United States's rail network, nearly all standard gauge, is the longest in the world, and exceeds 293,564 km (182,400 mi).[339] It handles mostly freight, with intercity passenger service primarily provided by Amtrak, a government-managed company that took over services previously run by private companies, to all but four states.[340][341]

Personal transportation in the United States is dominated by automobiles,[342][343] which operate on a network of 4 million miles (6.4 million kilometers) of public roads, making it the longest network in the world.[344][345] The Oldsmobile Curved Dash and the Ford Model T, both American cars, are considered the first mass-produced[346] and mass-affordable[347] cars, respectively. As of 2022, the United States is the second-largest manufacturer of motor vehicles[348] and is home to Tesla, the world's most valuable car company.[349] American automotive company General Motors held the title of the world's best-selling automaker from 1931 to 2008.[350] Currently, the American automotive industry is the world's second-largest automobile market by sales,[351] and the U.S. has the highest vehicle ownership per capita in the world, with 816.4 vehicles per 1000 Americans (2014).[352] In 2017, there were 255 million non-two wheel motor vehicles, or about 910 vehicles per 1000 people.[353]

The American civil airline industry is entirely privately owned and has been largely deregulated since 1978, while most major airports are publicly owned.[354] The three largest airlines in the world by passengers carried are U.S.-based; American Airlines is number one after its 2013 acquisition by US Airways.[355] Of the world's 50 busiest passenger airports, 16 are in the United States, including the top five and the busiest, Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport.[356][357] As of 2020, there are 19,919 airports in the United States, of which 5,217 are designated as "public use", including for general aviation and other activities.[358]

Of the fifty busiest container ports, four are located in the United States, of which the busiest is the Port of Los Angeles.[359] The country's inland waterways are the world's fifth-longest, and total 41,009 km (25,482 mi).[360]

Demographics

Population

The U.S. Census Bureau reported 331,449,281 residents as of April 1, 2020,[lower-alpha 13][361] making the United States the third-most populous nation in the world, after China and India.[362] According to the Bureau's U.S. Population Clock, on January 28, 2021, the U.S. population had a net gain of one person every 100 seconds, or about 864 people per day.[363] In 2018, 52% of Americans age 15 and over were married, 6% were widowed, 10% were divorced, and 32% had never been married.[364] In 2021, the total fertility rate for the U.S. stood at 1.7 children per woman,[365] and it had the world's highest rate of children (23%) living in single-parent households in 2019.[366]

The United States has a diverse population; 37 ancestry groups have more than one million members.[367] White Americans with ancestry from Europe, the Middle East or North Africa, form the largest racial and ethnic group at 57.8% of the United States population.[368][369] Hispanic and Latino Americans form the second-largest group and are 18.7% of the United States population. African Americans constitute the nation's third-largest ancestry group and are 12.1% of the total United States population.[367] Asian Americans are the country's fourth-largest group, composing 5.9% of the United States population, while the country's 3.7 million Native Americans account for about 1%.[367] In 2020, the median age of the United States population was 38.5 years.[362]

Language

While many languages are spoken in the United States, English is the most common.[370] Although there is no official language at the federal level, some laws—such as U.S. naturalization requirements—standardize English, and most states have declared English as the official language.[371] Three states and four U.S. territories have recognized local or indigenous languages in addition to English, including Hawaii (Hawaiian),[372] Alaska (twenty Native languages),[lower-alpha 14][373] South Dakota (Sioux),[374] American Samoa (Samoan), Puerto Rico (Spanish), Guam (Chamorro), and the Northern Mariana Islands (Carolinian and Chamorro). In Puerto Rico, Spanish is more widely spoken than English.[375]

According to the American Community Survey, in 2010 some 229 million people (out of the total U.S. population of 308 million) spoke only English at home. More than 37 million spoke Spanish at home, making it the second most commonly used language. Other languages spoken at home by one million people or more include Chinese (2.8 million), Tagalog (1.6 million), Vietnamese (1.4 million), French (1.3 million), Korean (1.1 million), and German (1 million).[376]

Immigration

America's immigrant population, numbering more than 50 million, is by far the world's largest in absolute terms.[377][378] In 2022, there were 87.7 million immigrants and U.S.-born children of immigrants in the United States, accounting for nearly 27% of the overall U.S. population.[379] In 2017, out of the U.S. foreign-born population, some 45% (20.7 million) were naturalized citizens, 27% (12.3 million) were lawful permanent residents, 6% (2.2 million) were temporary lawful residents, and 23% (10.5 million) were unauthorized immigrants.[380] In 2019, the top countries of origin for immigrants were Mexico (24% of immigrants), India (6%), China (5%), the Philippines (4.5%), and El Salvador (3%).[381] The United States has led the world in refugee resettlement for decades, admitting more refugees than the rest of the world combined.[382]

Urbanization

About 82% of Americans live in urban areas, including suburbs;[187] about half of those reside in cities with populations over 50,000.[383] In 2008, 273 incorporated municipalities had populations over 100,000, nine cities had more than one million residents, and four cities (New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Houston) had populations exceeding two million.[384] Many U.S. metropolitan populations are growing rapidly, particularly in the South and West.[385]

Largest metropolitan areas in the United States | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||

New York  Los Angeles |

1 | New York | Northeast | 19,768,458 | 11 | Boston | Northeast | 4,899,932 |  Chicago  Dallas–Fort Worth |

| 2 | Los Angeles | West | 12,997,353 | 12 | Riverside–San Bernardino | West | 4,653,105 | ||

| 3 | Chicago | Midwest | 9,509,934 | 13 | San Francisco | West | 4,623,264 | ||

| 4 | Dallas–Fort Worth | South | 7,759,615 | 14 | Detroit | Midwest | 4,365,205 | ||

| 5 | Houston | South | 7,206,841 | 15 | Seattle | West | 4,011,553 | ||

| 6 | Washington, D.C. | South | 6,356,434 | 16 | Minneapolis–Saint Paul | Midwest | 3,690,512 | ||

| 7 | Philadelphia | Northeast | 6,228,601 | 17 | San Diego | West | 3,286,069 | ||

| 8 | Atlanta | South | 6,144,050 | 18 | Tampa–St. Petersburg | South | 3,219,514 | ||

| 9 | Miami | South | 6,091,747 | 19 | Denver | West | 2,972,566 | ||

| 10 | Phoenix | West | 4,946,145 | 20 | Baltimore | South | 2,838,327 | ||

Education

American public education is operated by state and local governments and regulated by the United States Department of Education through restrictions on federal grants. In most states, children are required to attend school from the age of five or six (beginning with kindergarten or first grade) until they turn 18 (generally bringing them through twelfth grade, the end of high school); some states allow students to leave school at 16 or 17.[386] Of Americans 25 and older, 84.6% graduated from high school, 52.6% attended some college, 27.2% earned a bachelor's degree, and 9.6% earned graduate degrees.[387] The basic literacy rate is near-universal.[187][388] The country has the most Nobel Prize winners in history, with 403 (having won 406 awards).[389][390]

The United States has many private and public institutions of higher education including many of the world's top universities, as listed by various ranking organizations, are in the United States, including 19 of the top 25.[391][392][393] There are local community colleges with generally more open admission policies, shorter academic programs, and lower tuition.[394] The U.S. spends more on education per student than any nation in the world,[395] spending an average of $12,794 per year on public elementary and secondary school students in the 2016–2017 school year.[396]

As for public expenditures on higher education, the U.S. spends more per student than the OECD average, and more than all nations in combined public and private spending.[397] Despite some student loan forgiveness programs in place,[398] student loan debt has increased by 102% in the last decade,[399] and exceeded 1.7 trillion dollars as of 2022.[400]

Health

In a preliminary report, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced that U.S. life expectancy at birth was 76.4 years in 2021 (73.2 years for men and 79.1 years for women), down 0.9 years from 2020. The chief causes listed were the COVID-19 pandemic, accidents, drug overdoses, heart and liver disease, and suicides.[402][403] Life expectancy was highest among Asians and Hispanics and lowest among Blacks and American Indian–Alaskan Native (AIAN) peoples.[404][405] Starting in 1998, the life expectancy in the U.S. fell behind that of other wealthy industrialized countries, and Americans' "health disadvantage" gap has been increasing ever since.[406] The U.S. also has one of the highest suicide rates among high-income countries.[407] Approximately one-third of the U.S. adult population is obese and another third is overweight.[408] Poverty is the 4th leading risk factor for premature death in the United States annually, according to a 2023 study published in JAMA.[409][410]

The U.S. healthcare system far outspends that of any other nation, measured both in per capita spending and as a percentage of GDP, but attains worse healthcare outcomes when compared to peer nations.[411] The United States is the only developed nation without a system of universal healthcare, and a significant proportion of the population that does not carry health insurance.[412]

Government-funded healthcare coverage for the poor (Medicaid) and for those age 65 and older (Medicare) is available to Americans who meet the programs' income or age qualifications. In 2010, former President Obama passed the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act or ACA,[lower-alpha 15][413] with the law roughly halving the uninsured share of the population according to the CDC.[414] Its legacy remains controversial.[415]

Culture and society

Americans have traditionally been characterized by a unifying political belief in an "American creed" emphasizing liberty, equality under the law, democracy, social equality, property rights, and a preference for limited government.[417][418] Culturally, the country has been described as having the values of individualism and personal autonomy,[419][420] having a strong work ethic,[421] competitiveness,[422] and voluntary altruism towards others.[423][424][425] According to a 2016 study by the Charities Aid Foundation, Americans donated 1.44% of total GDP to charity, the highest in the world by a large margin.[426] Part of both the Anglosphere and Western World, the United States is also home to a wide variety of ethnic groups, traditions, and values,[427][428] and exerts major cultural influence on a global scale,[429][430] with the phenomenon being termed Americanization.[431] As such, the U.S. is considered a cultural superpower.[432]

Nearly all present Americans or their ancestors came from Eurafrasia ("the Old World") within the past five centuries.[433] Mainstream American culture is a Western culture largely derived from the traditions of European immigrants with influences from many other sources, such as traditions brought by slaves from Africa.[427][434] More recent immigration from Asia and especially Latin America has added to a cultural mix that has been described as a homogenizing melting pot, and a heterogeneous salad bowl, with immigrants contributing to, and often assimilating into, mainstream American culture.[427] The American Dream, or the perception that Americans enjoy high social mobility, plays a key role in attracting immigrants.[435] Whether this perception is accurate has been a topic of debate.[436][437][438] While mainstream culture holds that the United States is a classless society,[439] scholars identify significant differences between the country's social classes, affecting socialization, language, and values.[440] Americans tend to greatly value socioeconomic achievement, but being ordinary or average is promoted by some as a noble condition as well.[441]

The United States is considered to have the strongest protections of free speech of any country under the First Amendment,[442] which protects flag desecration, hate speech, blasphemy, and lese-majesty as forms of protected expression.[443][444][445] A 2016 Pew Research Center poll found that Americans were the most supportive of free expression of any polity measured.[446] They are also the "most supportive of freedom of the press and the right to use the Internet without government censorship."[447] It is a socially progressive country[448] with permissive attitudes surrounding human sexuality.[449] LGBT rights in the United States are among the most advanced in the world.[449][450][451]

Mass media

The four major broadcasters in the U.S. are the National Broadcasting Company (NBC), Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), American Broadcasting Company (ABC), and Fox Broadcasting Company (FOX). The four major broadcast television networks are all commercial entities. Cable television offers hundreds of channels catering to a variety of niches.[452] As of 2021, about 83% of Americans over age 12 listen to broadcast radio, while about 41% listen to podcasts.[453] As of September 30, 2014, there are 15,433 licensed full-power radio stations in the U.S. according to the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC).[454] Much of the public radio broadcasting is supplied by NPR, incorporated in February 1970 under the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967.[455]

Globally-recognized newspapers in the United States include The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The Washington Post, and USA Today.[456] More than 800 publications are produced in Spanish, the second most commonly used language in the United States behind English.[457][458] With very few exceptions, all the newspapers in the U.S. are privately owned, either by large chains such as Gannett or McClatchy, which own dozens or even hundreds of newspapers; by small chains that own a handful of papers; or, in a situation that is increasingly rare, by individuals or families. Major cities often have alternative newspapers to complement the mainstream daily papers, such as The Village Voice in New York City and LA Weekly in Los Angeles. The five most popular websites used in the U.S. are Google, YouTube, Amazon, Yahoo, and Facebook, with all of them being American companies.[459]

As of 2022, the video game market of the United States is the world's largest by revenue.[460] Major video game publishers and developers headquartered in the United States are Sony Interactive Entertainment, Take-Two, Activision Blizzard, Electronic Arts, Xbox Game Studios, Bethesda Softworks, Epic Games, Valve, Warner Bros., Riot Games, and others.[461][462] There are 444 publishers, developers, and hardware companies in California alone.[463]

Religion

The First Amendment guarantees the free exercise of religion and forbids Congress from passing laws respecting its establishment.[465][466] Religious practice is widespread, among the most diverse in the world,[467] and vibrant, with the country being far more religious than other wealthy Western nations.[468] An overwhelming majority of Americans believe in a higher power,[469] engage in spiritual practices such as prayer,[470] and consider themselves religious.[471][472] The country has the world's largest Christian population.[473] A majority of the global Jewish population lives in the United States, as measured by the Law of Return.[474]

A 2022 Gallup poll found that 31% reported "attending a church, synagogue, mosque or temple weekly or nearly weekly".[475] Religious practice varies significantly by region.[476] In the "Bible Belt", located within the Southern United States, evangelical Protestantism plays a significant role culturally. New England and the Western United States tend to be less religious,[476] although Mormonism—a Restorationist Christian movement started in New York in the 19th century—is the predominant religious affiliation in Utah.[477] Around 6% of Americans claim a non-Christian faith.[478] the largest of which are Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism.[479] "Ceremonial deism" is common in American culture.[480] Religious belief and interest has remained relatively stable in recent years; organizational participation, in contrast, has decreased.[481]

Other notable faiths include Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, many New Age movements, and a large variety of Native American religions.[482]

Literature and visual arts

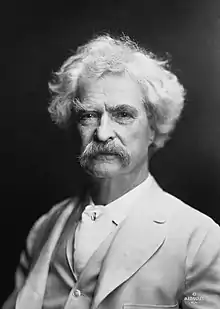

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, American art and literature took most of their cues from Europe. Writers such as Washington Irving, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Edgar Allan Poe, and Henry David Thoreau established a distinctive American literary voice by the middle of the 19th century. Mark Twain and poet Walt Whitman were major figures in the century's second half; Emily Dickinson, virtually unknown during her lifetime, is recognized as an essential American poet.[484]

Almost until the 20th century pervasive anti-literacy laws prevented most people of color from learning to read or write.[485][486] In the 1920s, the New Negro Movement coalesced in Harlem, where many writers had migrated from the Southern United States and West Indies. Its pan-African perspective was a significant cultural export during the Jazz Age in Paris and as such was a key early influence on the négritude philosophy.[487]

Since its first use in the 19th century, the term "Great American Novel" has been applied to many books, including Herman Melville's Moby-Dick (1851), Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852), Twain's The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885), F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby (1925), John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath (1939), Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird (1960), Toni Morrison's Beloved (1987), and David Foster Wallace's Infinite Jest (1996).[488][489][490]

Thirteen U.S. citizens have won the Nobel Prize in Literature, most recently Louise Glück, Bob Dylan, and Toni Morrison.[491] Earlier laureates William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway and John Steinbeck have also been recognized as influential 20th century writers.[492]

In the visual arts, the Hudson River School was a mid-19th-century movement in the tradition of European naturalism. The 1913 Armory Show in New York City, an exhibition of European modernist art, shocked the public and transformed the U.S. art scene.[493] Georgia O'Keeffe, Marsden Hartley, and others experimented with new, individualistic styles, which would become known as American modernism.

Major artistic movements such as the abstract expressionism of Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning and the pop art of Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein developed largely in the United States. Major photographers include Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen, Dorothea Lange, Edward Weston, James Van Der Zee, Ansel Adams, and Gordon Parks.[494]

The uniquely American "Chicago School" refers to two architectural styles derived from the architecture of Chicago. In the history of architecture, the first Chicago School was a school of architects active in Chicago in the late 19th, and at the turn of the 20th century. They were among the first to promote the new technologies of steel-frame construction in commercial buildings, and developed a spatial aesthetic which co-evolved with, and then came to influence, parallel developments in European modernism. Much of its early work is also known as "Commercial Style".[495] A "Second Chicago School" with a modernist aesthetic emerged in the 1940s through 1970s, which pioneered new building technologies and structural systems, such as the tube-frame structure.[496] The tide of modernism and then postmodernism has brought global fame to American architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Philip Johnson, and Frank Gehry.[497] Other Americans who have had dramatic influences on national and international architecture include Maya Lin, Frederick Law Olmstead, I.M. Pei, and Stanford White.

Cinema and theater

The United States is well known for its cinema and theater. Its movie industry has a worldwide influence and following. Hollywood, a district in northern Los Angeles, the nation's second-most populous city, is the leader in motion picture production and the most recognizable movie industry in the world.[498][499][500] The major film studios of the United States are the primary source of the most commercially successful and most ticket-selling movies in the world.[501][502]

.jpg.webp)

Since the early 20th century, the U.S. film industry has largely been based in and around Hollywood, although in the 21st century an increasing number of films are not made there, and film companies have been subject to the forces of globalization.[503] The Academy Awards, popularly known as the Oscars, have been held annually by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences since 1929,[504] and the Golden Globe Awards have been held annually since January 1944.[505]

Director D. W. Griffith's film adaptation of The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan was the first American blockbuster, earning the equivalent of $1.8 billion in current dollars. The technical achievements of the film revolutionized film grammar, while its subject matter caused both strident protest and a revitalization of the Klan.[506] Producer and entrepreneur Walt Disney was a leader in both animated film and movie merchandising.[507] Directors such as John Ford redefined the image of the American Old West, and, like others such as John Huston, broadened the possibilities of cinema with location shooting. The industry enjoyed its golden years, in what is commonly referred to as the "Golden Age of Hollywood", from the early sound period until the early 1960s,[508] with screen actors such as John Wayne and Marilyn Monroe becoming iconic figures.[509][510] In the 1970s, "New Hollywood" or the "Hollywood Renaissance"[511] was defined by grittier films influenced by French and Italian realist pictures of the post-war period.[512]

The 21st century has been marked by the rise of American streaming platforms, such as Netflix, Disney+, Paramount+, and Apple TV+, which came to rival traditional cinema.[513][514]

Mainstream theater in the United States derives from the old European theatrical tradition and has been heavily influenced by the British theater.[515] In the 19th century, America had created new dramatic forms in the Tom Shows, the showboat theater and the minstrel show.[516] The central hub of the American theater scene is Manhattan, with its divisions of Broadway, off-Broadway, and off-off-Broadway.[517] Many movie and television stars have gotten their big break working in New York productions. Outside New York City, many cities have professional regional or resident theater companies that produce their own seasons. The biggest-budget theatrical productions are musicals. U.S. theater also has an active community theater culture.[518]

Music

American folk music encompasses numerous music genres, variously known as traditional music, traditional folk music, contemporary folk music, or roots music. Many traditional songs have been sung within the same family or folk group for generations, and sometimes trace back to such origins as the British Isles, Mainland Europe, or Africa.[519]