Flumezapine

Flumezapine is an abandoned, investigational antipsychotic drug that was studied for the treatment of schizophrenia. Flumezapine failed clinical trials due to concern for liver and muscle toxicity. Flumezapine is structurally related to the common antipsychotic olanzapine—a point that was used against its manufacturer, Eli Lilly and Company, in a lawsuit in which generic manufacturers sought to void the patent on brand name olanzapine (Zyprexa). Although flumezapine does not differ greatly from olanzapine in terms of its structure, the difference was considered to be non-obvious, and Eli Lilly's patent rights on Zyprexa were upheld.

| |

| |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H19FN4S |

| Molar mass | 330.43 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

Medical uses

Flumezapine was studied for the treatment of schizophrenia.[1]

Adverse effects

In the clinical trial that lead to the cessation of its development as a drug, flumezapine was noted to be toxic. The administration of flumezapine led to the adverse effects of elevating the plasma concentration of creatine phosphokinase (CPK) and the liver enzymes aspartate transaminase (AST) and alanine transaminase (ALT).[1] These liver enzyme elevation risks are similar to that of the neuroleptic drug chlorpromazine.[1] Flumezapine also induced extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) in patients during early clinical trials.[1]

Pharmacology

Flumezapine is classified as a second-generation antipsychotic, which includes other drugs such as clozapine.[2]

Mechanism of action

Flumezapine is an antipsychotic, due to its antagonism of dopamine receptors in the brain. However, like other antipsychotics, it also antagonizes other receptors in the brain, such as the muscarinic receptors. In comparison to clozapine, another antipsychotic, flumezapine's antidopaminergic to anticholinergic ratio is 5 times higher, indicating higher dopamine receptor blockade with less anticholingergic properties.[3]

Chemistry

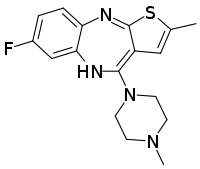

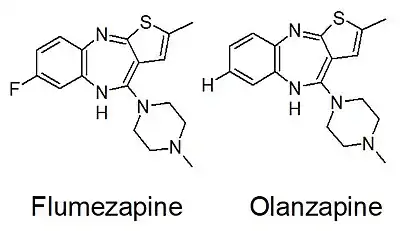

Flumezapine is a thioeno[2,3-b][1,5]benzodiazepine akin to olanzapine, differing only by the substitution of a fluorine atom (F) for a hydrogen atom (H) on the phenyl ring.[4] The fluorine atom acts as an electron-withdrawing substituent; this was the same rationale given in the patent information for the electron-withdrawing chlorine atom on the antipsychotic clozapine.[5]

History

Developed alongside olanzapine by Eli Lilly and Company, the clinical development of flumezapine was halted due to toxicology concerns.[6] Its research designation was LY-120363.[7] The other analogues studied, (1) substituting flumezapine's methyl group for an ethyl group (ethyl flumezapine)[8] and (2) substituting flumezapine's methyl group for an ethyl group and its fluorine atom for a hydrogen atom, also failed due to concerns of granulocyte suppression and elevated cholesterol during in vivo studies on dogs, respectively.[9]

Society and culture

Controversies

In 2005, flumezapine was at the heart of a lawsuit filed by drug manufacturer Eli Lilly against three generic drug manufacturers (Zenith Goldline Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Reddy's Laboratories, and Teva Pharmaceuticals) that sought to develop generic versions of Zyprexa (olanzapine).[10] The generic companies claimed the Eli Lilly's patent on olanzapine was null and void due to the expiration of the similar compound, flumezapine, from which the discovery of olanzapine would be inevitable.[10] In the judge's ruling, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Indiana sided with Eli Lilly by upholding Eli Lilly's patent (Patent No. 5,229,382), finding that the substitution of a fluorine atom for a hydrogen atom in olanzapine was a non-obvious difference between the two compounds, which deserved continued patent protection.[10][11] As Nicole L. M. Valtz writes in her commentary on the case,

"Mere identification in the prior art of each component of a composition does not render the combination obvious; the law requires some motivation to select and combine the references to reach the claimed invention."[12]

The selection patent was also upheld in Canada.[13] The patent for Zyprexa expired in 2011.[10]

References

- US 5229382, Chakrabarti JK, Hotten TM, Tupper DE, "2-Methyl-thieno-benzodiazepine", issued 20 July 1993, assigned to Lilly Industries Ltd.

- Altar CA, Boyar WC, Wasley A, Gerhardt SC, Liebman JM, Wood PL (August 1988). "Dopamine neurochemical profile of atypical antipsychotics resembles that of D-1 antagonists". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 338 (2): 162–168. doi:10.1007/bf00174864. PMID 2903451. S2CID 20765461.

- de Paulis T (1983). "3. Antipsychotic Agents and Dopamine Agonists". Annual Reports in Medicinal Chemistry. Academic Press. p. 21. ISBN 0080583628.

- Liegeois JF, Bruhwyler J, Rogister F, Delarge J (1995). "Diarylazepine derivatives as potent atypical neuroleptic drugs: recent advances". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 1 (6): 471–501. doi:10.2174/092986730106220216114910. S2CID 87829622.

- Bausch T (2018). "The Olanzapine Case and Its Implications for Novelty of Chemical-substance Patents in Europe --- China Intellectual Property". www.chinaipmagazine.com. China Intellectual Property Magazine. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- "Lilly holds onto Zyprexa patent". Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 4 (6): 450. May 24, 2005. doi:10.1038/nrd1758. S2CID 52886898.

- Milne GW, ed. (2018). Drugs: Synonyms and Properties: Synonyms and Properties. Routledge. ISBN 9781351789899.

- Mallon J, Dai J (February 21, 2012). "Lead Compound Obviousness Analysis". sdipla.org. San Diego Intellectual Property Legal Association. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- "Case Histories & SMR Award Lecture" (PDF). smr.org.uk. The Society for Medicines Research. December 2, 1999. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- Berenson A (April 15, 2005). "Judge Upholds Lilly Drug Patent". The New York Times. Retrieved June 2, 2018.

- Liang G (2012). "The Validity Challenge to Compound Claims and the (Un?)Predictability of Chemical Arts" (PDF). Wake Forest Journal of Business and Intellectual Property Law. 13 (1): 54–57. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- Valtz N (2007). "Structurally Similar Chemical Compounds Alone Do Not Render a Compound Obvious". Last Month at the Federal Circuit: 9–10. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- Harrison C (March 2010). "Patent watch". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 9 (3): 184–185. doi:10.1038/nrd3273. PMID 20190782. S2CID 27510444.