Levantine Arabic

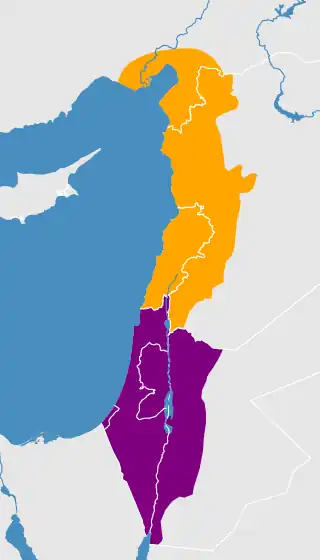

Levantine Arabic, also called Shami (autonym: شامي šāmi or اللهجة الشامية el-lahje š-šāmiyye), is an Arabic variety spoken in the Levant: in Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Israel, and southern Turkey (historically in Adana, Mersin and Hatay only). With over 44 million speakers, Levantine is, alongside Egyptian, one of the two prestige varieties of spoken Arabic comprehensible all over the Arab world.

| Levantine Arabic | |

|---|---|

| شامي šāmi | |

| Native to | Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Israel, Turkey |

| Region | Levant[lower-alpha 1][1][2] |

| Ethnicity | Primarily Arabs

|

| Speakers | L1: 47 million (2003–2021)[4] L2: 360,000[4] Total speakers: 48 million[4] |

| Dialects | |

| Levantine Arabic Sign Language | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | apc |

| Glottolog | nort3139 |

| Linguasphere | 12-AAC-eh "Syro-Palestinian" |

| IETF | apc |

Modern distribution of Levantine | |

Levantine is not officially recognized in any state or territory. Although it is the majority language in Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria, it is predominantly used as a spoken vernacular in daily communication, whereas most written and official documents and media in these countries use the official Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), a form of literary Arabic only acquired through formal education that does not function as a native language. In Israel and Turkey, Levantine is a minority language.

The Palestinian dialect is the closest vernacular Arabic variety to MSA, with about 50% of common words. Nevertheless, Levantine and MSA are not mutually intelligible. Levantine speakers therefore often call their language العامية al-ʿāmmiyya ⓘ, 'slang', 'dialect', or 'colloquial'. However, with the emergence of social media, attitudes toward Levantine have improved. The amount of written Levantine has significantly increased, especially online, where Levantine is written using Arabic, Latin, or Hebrew characters. Levantine pronunciation varies greatly along social, ethnic, and geographical lines. Its grammar is similar to that shared by most vernacular varieties of Arabic. Its lexicon is overwhelmingly Arabic, with a significant Aramaic influence.

The lack of written sources in Levantine makes it impossible to determine its history before the modern period. Aramaic was the dominant language in the Levant starting in the 1st millennium BCE; it coexisted with other languages, including many Arabic dialects spoken by various Arab tribes. With the Muslim conquest of the Levant in the 7th century, new Arabic speakers from the Arabian Peninsula settled in the area, and a lengthy language shift from Aramaic to vernacular Arabic occurred.

Naming and classification

Scholars use "Levantine Arabic" to describe the continuum of mutually intelligible dialects spoken across the Levant.[14][15][16] Other terms include "Syro-Palestinian",[17] "Eastern Arabic",[lower-alpha 2][19] "East Mediterranean Arabic",[20] "Syro-Lebanese" (as a broad term covering Jordan and Palestine as well),[21] "Greater Syrian",[22] or "Syrian Arabic" (in a broad meaning, referring to all the dialects of Greater Syria, which corresponds to the Levant).[1][2] Most authors only include sedentary dialects,[23] excluding Bedouin dialects of the Syrian Desert and the Negev, which belong to the dialects of the Arabian peninsula. Mesopotamian dialects from northeast Syria are also excluded.[21] Other authors include Bedouin varieties.[24]

The term "Levantine Arabic" is not indigenous and, according to linguists Kristen Brustad and Emilie Zuniga, "it is likely that many speakers would resist the grouping on the basis that the rich phonological, morphological and lexical variation within the Levant carries important social meanings and distinctions."[24] Levantine speakers often call their language العامية al-ʿāmmiyya, 'slang', 'dialect', or 'colloquial' (lit. 'the language of common people'), to contrast it to Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) and Classical Arabic (الفصحى al-fuṣḥā, lit. 'the eloquent').[lower-alpha 3][26][27][28] They also call their spoken language عربي ʿarabiyy, 'Arabic'.[29] Alternatively, they identify their language by the name of their country.[4][30] شامي šāmi can refer to Damascus Arabic, Syrian Arabic, or Levantine as a whole.[31][4] Lebanese literary figure Said Akl led a movement to recognize the "Lebanese language" as a distinct prestigious language instead of MSA.[32]

Levantine is a variety of Arabic, a Semitic language. There is no consensus regarding the genealogical position of Arabic within the Semitic languages.[33] The position of Levantine and other Arabic vernaculars in the Arabic macrolanguage family has also been contested. According to the Arabic tradition, Classical Arabic was the spoken language of the pre-Islamic and Early Islamic periods and remained stable until today's MSA.[25] According to this view, all Arabic vernaculars, including Levantine, descend from Classical Arabic and were corrupted by contacts with other languages.[34][35] Several Arabic varieties are closer to other Semitic languages and maintain features not found in Classical Arabic, indicating that these varieties cannot have developed from Classical Arabic.[36][37] Thus, Arabic vernaculars are not a modified version of the Classical language,[38] which is a sister language rather than their direct ancestor.[39] Classical Arabic and vernacular varieties all developed from an unattested common ancestor, Proto-Arabic.[39][40] The ISO 639-3 standard classifies Levantine as a language, member of the macrolanguage Arabic.[41]

Sedentary vernaculars (also called dialects) are traditionally classified into five groups according to shared features: Peninsular, Mesopotamian, Levantine, Egyptian, and Maghrebi.[42][22] The linguistic distance between these vernaculars is at least as large as between Germanic languages or Romance languages. It is, for instance, extremely difficult for Moroccans and Iraqis, each speaking their own variety, to understand each other.[43] Levantine and Egyptian are the two prestige varieties of spoken Arabic;[44][45][46] they are also the most widely understood dialects in the Arab world[24] and the most commonly taught to non-native speakers outside the Arab world.[45]

Geographical distribution and varieties

Dialects

Levantine is spoken in the fertile strip on the eastern shores of the Mediterranean: from the Turkish coastal provinces of Adana, Hatay, and Mersin in the north[47] to the Negev, passing through Lebanon, the coastal regions of Syria (Latakia and Tartus governorates) as well as around Aleppo and Damascus,[4] the Hauran in Syria and Jordan,[48][49] the rest of western Jordan,[50] Palestine and Israel.[4] Other Arabic varieties border it: Mesopotamian and North Mesopotamian Arabic to the north and north-east; Najdi Arabic to the east and south-east; and Northwest Arabian Arabic to the south and south-west.[50][51]

The similarity among Levantine dialects transcends geographical location and political boundaries. The urban dialects of the main cities (such as Damascus, Beirut, and Jerusalem) have much more in common with each other than they do with the rural dialects of their respective countries. The sociolects of two different social or religious groups within the same country may also show more dissimilarity with each other than when compared with their counterparts in another country.[1]

The process of linguistic homogenization within each country of the Levant makes a classification of dialects by country possible today.[52][22] Linguist Kees Versteegh classifies Levantine into three groups: Lebanese/Central Syrian (including Beirut, Damascus, Druze Arabic, Cypriot Maronite[lower-alpha 4]), North Syrian (including Aleppo), and Palestinian/Jordanian.[48] He writes that distinctions between these groups are unclear, and isoglosses cannot determine the exact boundary.[55] Mutual intelligibility between these varieties is very high.[4]

The dialect of Aleppo shows Mesopotamian influence.[4] The prestige dialect of Damascus is the most documented Levantine dialect.[24] A "common Syrian Arabic" is emerging.[56] Similarly, a "Standard Lebanese Arabic" is emerging, combining features of Beiruti Arabic (which is not prestigious) and Jabale Arabic, the language of Mount Lebanon.[57][58] In Çukurova, Turkey, the local dialect is endangered.[59][60] Bedouin varieties are spoken in the Negev and the Sinai Peninsula, areas of transition between Levantine and Egyptian.[61][62][63] The dialect of Arish, Egypt, is classified by Linguasphere as Levantine.[17] The Amman dialect is emerging as an urban standard in Jordanian Arabic,[64][65] while other Jordanian and Palestinian Arabic dialects include Fellahi (rural) and Madani (urban).[4][66][67] The Gaza dialect contains features of both urban Palestinian and Bedouin Arabic.[68]

Ethnicity and religion

The Levant is characterized by ethnic diversity and religious pluralism.[69] Levantine dialects vary along sectarian lines.[24] Religious groups include Sunni Muslims, Shia Muslims, Alawites, Christians, Druze, and Jews.[70][71] Differences between Muslim and Christian dialects are minimal, mainly involving some religious vocabulary.[72] A minority of features are perceived as typically associated with one group. For example, in Beirut, the exponent تاع tēʕ is only used by Muslims and never by Christians who use تبع tabaʕ.[73] Contrary to others, Druze and Alawite dialects retained the phoneme /q/.[24] MSA influences Sunni dialects more. Jewish dialects diverge more from Muslim dialects and often show influences from other towns due to trade networks and contacts with other Jewish communities.[74] For instance, the Jewish dialect of Hatay is very similar to the Aleppo dialect, particularly the dialect of the Jews of Aleppo. It shows traits otherwise not found in any dialect of Hatay.[74][59] Koineization in cities such as Damascus leads to a homogenization of the language among religious groups.[75] In contrast, the marginalization of Christians in Jordan intensifies linguistic differences between Christian Arabs and Muslims.[76]

Levantine is primarily spoken by Arabs. It is also spoken as a first or second language by several ethnic minorities.[3] In particular, it is spoken natively by Samaritans[77] and by most Circassians in Jordan,[78][79] Armenians in Jordan[80] and Israel,[81] Assyrians in Israel,[81] Turkmen in Syria[82] and Lebanon,[83] Kurds in Lebanon,[84][85] and Dom people in Jerusalem.[86][87] Most Christian and Muslim Lebanese people in Israel speak Lebanese Arabic.[88][lower-alpha 5] Syrian Jews,[71] Lebanese Jews,[90] and Turkish Jews from Çukurova are native Levantine speakers; however, most moved to Israel after 1948.[59] Levantine was spoken natively by most Jews in Jerusalem, but the community shifted to Modern Hebrew after the establishment of Israel.[91][92] Levantine is the second language of Dom people across the Levant,[93][4] Circassians in Israel,[4] Armenians in Lebanon,[94] Chechens in Jordan,[79][80] Assyrians in Syria[4] and Lebanon,[95][96] and most Kurds in Syria.[4][97]

Speakers by country

In addition to the Levant, where it is indigenous, Levantine is spoken among diaspora communities from the region, especially among the Palestinian,[67] Lebanese, and Syrian diasporas.[98] The language has fallen into disuse among subsequent diaspora generations, such as the 7 million Lebanese Brazilians.[99][4]

| Country | Total population | Levantine speakers[4] |

|---|---|---|

| 18 million[100] | 15 million | |

| 10 million[101] | 8 million | |

| 7 million[102] | 7 million | |

| 5 million[103] | 4 million | |

| 85 million[104] | 4 million | |

| 9 million[105] | 2 million | |

| 36 million[106] | 1 million | |

| 3 million[107] | 1 million | |

| 83 million[108] | 800,000 | |

| 214 million[109] | 700,000 | |

| 10 million[110] | 700,000 | |

| 333 million[111] | 600,000 | |

| 4 million[112] | 400,000 | |

| 272 million[113] | 300,000 | |

| 39 million[114] | 300,000 | |

| 104 million[115] | 200,000 | |

| 26 million[116] | 200,000 | |

| 30 million[117] | 100,000 |

History

Pre-Islamic antiquity

Starting in the 1st millennium BCE, Aramaic was the dominant spoken language and the language of writing and administration in the Levant.[118] Greek was the language of administration of the Seleucid Empire (in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE[119]) and was maintained by the Roman (64 BCE–475 CE[120][121]), then Byzantine (476–640[121][120]) empires.[119] From the early 1st millennium BCE until the 6th century CE, there was a continuum of Central Semitic languages in the Arabian Peninsula, and Central Arabia was home to languages quite distinct from Arabic.[122]

Because there are no written sources, the history of Levantine before the modern period is unknown.[123] Old Arabic was a dialect continuum stretching from the southern Levant (where Northern Old Arabic was spoken) to the northern Hijaz, in the Arabian Peninsula, where Old Hijazi was spoken.[124] In the early 1st century CE, a great variety of Arabic dialects were already spoken by various nomadic or semi-nomadic Arabic tribes in the Levant,[125][126][56] such as the Nabataeans[127]—who used Aramaic for official purposes,[128] the Tanukhids,[127] and the Ghassanids.[79] These dialects were local, coming from the Hauran—and not from the Arabian peninsula—[129] and related to later Classical Arabic.[127] Initially restricted to the steppe, Arabic-speaking nomads started to settle in cities and fertile areas after the Plague of Justinian in 542 CE.[129] These Arab communities stretched from the southern extremities of the Syrian Desert to central Syria, the Anti-Lebanon Mountains, and the Beqaa Valley.[130][131]

Muslim conquest of the Levant

The Muslim conquest of the Levant (634–640[121][120]) brought Arabic speakers from the Arabian Peninsula who settled in the Levant.[132] Arabic became the language of trade and public life in cities, while Aramaic continued to be spoken at home and in the countryside.[131] Arabic gradually replaced Greek as the language of administration in 700 by order of the Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik.[133][134] The language shift from Aramaic to vernacular Arabic was a long process over several generations, with an extended period of bilingualism, especially among non-Muslims.[131][135] Christians continued to speak Syriac for about two centuries, and Syriac remained their literary language until the 14th century.[136][134] In its spoken form, Aramaic nearly disappeared, except for a few Aramaic-speaking villages,[134] but it has left substrate influences on Levantine.[135]

Different Peninsular Arabic dialects competed for prestige, including the Hijazi vernacular of the Umayyad elites. In the Levant, these Peninsular dialects mixed with ancient forms of Arabic, such as the northern Old Arabic dialect.[137] By the mid-6th century CE, the Petra papyri show that the onset of the article and its vowel seem to have weakened. The article is sometimes written as /el-/ or simply /l-/. A similar, but not identical, situation is found in the texts from the Islamic period. Unlike the pre-Islamic attestations, the coda of the article in 'conquest Arabic' assimilates to a following coronal consonant.[138] According to Pr. Simon Hopkins, this document shows that there is "a very impressive continuity in colloquial Arabic usage, and the roots of the modern vernaculars are thus seen to lie very deep".[139]

Medieval and early modern era

The Damascus Psalm Fragment, dated to the 9th century but possibly earlier, sheds light on the Damascus dialect of that period. Because its Arabic text is written in Greek characters, it reveals the pronunciation of the time;[140] it features many examples of imāla (the fronting and raising of /a/ toward /i/).[141] It also features a pre-grammarian standard of Arabic and the dialect from which it sprung, likely Old Hijazi.[142] Scholars disagree on the dates of phonological changes. The shift of interdental spirants to dental stops dates to the 9th to 10th centuries or earlier.[143] The shift from /q/ to a glottal stop is dated between the 11th and 15th centuries.[144] Imāla seems already important in pre-Islamic times.[141]

Swedish orientalist Carlo Landberg writes about the vulgarisms encountered in Damascene poet Usama ibn Munqidh's Memoirs: "All of them are found in today's spoken language of Syria and it is very interesting to note that that language is, on the whole, not very different from the language of ˀUsāma's days", in the 12th century.[139] Lucas Caballero's Compendio (1709) describes spoken Damascene Arabic in the early 1700s. It corresponds to modern Damascene in some respects, such as the allomorphic variation between -a/-e in the feminine suffix. On the contrary, the insertion and deletion of vowels differ from the modern dialect.[145]

From 1516 to 1918, the Ottoman Empire dominated the Levant. Many Western words entered Arabic through Ottoman Turkish as it was the main language for transmitting Western ideas into the Arab world.[146][147]

20th and 21st centuries

The dissolution of the Ottoman Empire in the early 20th century reduced the use of Turkish words due to Arabization and the negative perception of the Ottoman era among Arabs.[148] With the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon (1920–1946),[149] the British protectorate over Jordan (1921–1946), and the British Mandate for Palestine (1923–1948), French and English words gradually entered Levantine Arabic.[3][150] Similarly, Modern Hebrew has significantly influenced the Palestinian dialect of Arab Israelis since the establishment of Israel in 1948.[151] In the 1960s, Said Akl—inspired by the Maltese and Turkish alphabets—[152] designed a new Latin alphabet for Lebanese and promoted the official use of Lebanese instead of MSA,[153] but this movement was unsuccessful.[154][155]

Although Levantine dialects have remained stable over the past two centuries, in cities such as Amman[65] and Damascus, language standardization occurs through variant reduction and linguistic homogenization among the various religious groups and neighborhoods. Urbanization and the increasing proportion of youth[lower-alpha 7] constitute the causes of dialect change.[75][22] Urban forms are considered more prestigious,[157] and prestige dialects of the capitals are replacing the rural varieties.[48] With the emergence of social media, the amount of written Levantine has also significantly increased online.[158]

Status and usage

Diglossia and code-switching

Levantine is not recognized in any state or territory.[159][23] MSA is the sole official language in Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria;[23] it has a "special status" in Israel under the Basic Law.[160] French is also recognized in Lebanon.[94] In Turkey, the only official language is Turkish.[59] Any variation from MSA is considered a "dialect" of Arabic.[161] As in the rest of the Arab world, this linguistic situation has been described as diglossia: MSA is nobody's first acquired language;[162] it is learned through formal instruction rather than transmission from parent to child.[162] This diglossia has been compared to the use of Latin as the sole written, official, liturgical, and literary language in Europe during the medieval period, while Romance languages were the spoken languages.[163][164] Levantine and MSA are mutually unintelligible.[165][166] They differ significantly in their phonology, morphology, lexicon and syntax.[2][46][167]

MSA is the language of literature, official documents, and formal written media (newspapers, instruction leaflets, school books).[162] In spoken form, MSA is mostly used when reading from a scripted text (e.g., news bulletins) and for prayer and sermons in the mosque or church.[162] In Israel, Hebrew is the language used in the public sphere, except internally among the Arab communities.[160][168] Levantine is the usual medium of communication in all other domains.[162]

Traditionally in the Arab world, colloquial varieties, such as Levantine, have been regarded as corrupt forms of MSA, less eloquent and not fit for literature, and thus looked upon with disdain.[169][170] Because the French and the British emphasized vernaculars when they colonized the Arab world, dialects were also seen as a tool of colonialism and imperialism.[171][172] Writing in the vernacular has been controversial because pan-Arab nationalists consider that this might divide the Arab people into different nations.[173][159] On the other hand, Classical Arabic is seen as "the language of the Quran" and revered by Muslims who form the majority of the population.[173] It is believed to be pure and everlasting, and Islamic religious ideology considers vernaculars to be inferior.[174][175] Until recently, the use of Levantine in formal settings or written form was often ideologically motivated, for instance in opposition to pan-Arabism.[175] Language attitudes are shifting, and using Levantine became de-ideologized for most speakers by the late 2010s.[175] Levantine is now regarded in a more positive light, and its use in informal modes of writing is acknowledged, thanks to its recent widespread use online in both written and spoken forms.[176][177]

Code-switching between Levantine, MSA, English, French (in Lebanon and among Arab Christians in Syria[56]), and Hebrew (in Israel[178][9]) is frequent among Levantine speakers, in both informal and formal settings (such as on television).[179] Gordon cites two Lebanese examples: "Bonjour, ya habibti, how are you?" ("Hello, my love, how are you?") and "Oui, but leish?" ("Yes, but why?").[180] Code-switching also happens in politics. For instance, not all politicians master MSA in Lebanon, so they rely on Lebanese. Many public and formal speeches and most political talk shows are in Lebanese instead of MSA.[57] In Israel, Arabic and Hebrew are allowed in the Knesset, but Arabic is rarely used.[181] MK Ahmad Tibi often adds Palestinian Arabic sentences to his Hebrew speech but only gives partial speeches in Arabic.[182]

Education

In the Levant, MSA is the only variety authorized for use in schools,[162] although in practice, lessons are often taught in a mix of MSA and Levantine with, for instance, the lesson read out in MSA and explained in Levantine.[56][23] In Lebanon, about 50% of school students study in French.[183] In most Arab universities, the medium of instruction is MSA in social sciences and humanities, and English or French in the applied and medical sciences. In Syria, only MSA is used.[162][184][79] In Turkey, article 42.9 of the Constitution prohibits languages other than Turkish from being taught as a mother tongue and almost all Arabic speakers are illiterate in Arabic unless they have learned MSA for religious purposes.[70]

In Israel, MSA is the only language of instruction in Arab schools. Hebrew is studied as a second language by all Palestinian students from at least the second grade and English from the third grade.[185][168] In Jewish schools, in 2012, 23,000 pupils were studying spoken Palestinian in 800 elementary schools. Palestinian Arabic is compulsory in Jewish elementary schools in the Northern District; otherwise, Jewish schools teach MSA.[186] Junior high schools must teach all students MSA, but only two-thirds meet this obligation.[187] At all stages in 2012, 141,000 Jewish students were learning Arabic.[188] In 2020, 3.7% of Jewish students took the Bagrut exam in MSA.[187]

Films and music

Most films and songs are in vernacular Arabic.[26] Egypt was the most influential center of Arab media productions (movies, drama, TV series) during the 20th century,[189] but Levantine is now competing with Egyptian.[190] As of 2013, about 40% of all music production in the Arab world was in Lebanese.[189] Lebanese television is the oldest and largest private Arab broadcast industry.[191] Most big-budget pan-Arab entertainment shows are filmed in the Lebanese dialect in the studios of Beirut. Moreover, the Syrian dialect dominates in Syrian TV series (such as Bab Al-Hara) and in the dubbing of Turkish television dramas (such as Noor), famous across the Arab world.[189][192]

As of 2009, most Arabic satellite television networks use colloquial varieties in their programs, except news bulletins in MSA. The use of vernacular in broadcasting started in Lebanon during the Lebanese Civil War and expanded to the rest of the Arab world. In 2009, Al Jazeera used MSA only and Al Arabiya and Al-Manar used MSA or a hybrid between MSA and colloquial for talk shows.[179] On the popular Lebanese satellite channel Lebanese Broadcasting Corporation International (LBCI), Arab and international news bulletins are only in MSA, while the Lebanese national news broadcast is in a mix of MSA and Lebanese Arabic.[193]

Written media

Levantine is seldom written, except for some novels, plays, and humorous writings.[194][195] Most Arab critics do not acknowledge the literary dignity of prose in dialect.[196] Prose written in Lebanese goes back to at least 1892 when Tannus al-Hurr published Riwāyat aš-šābb as-sikkīr ʾay Qiṣṣat Naṣṣūr as-Sikrī, 'The tale of the drunken youth, or The story of Nassur the Drunkard'.[195] In the 1960s, Said Akl led a movement in Lebanon to replace MSA as the national and literary language, and a handful of writers wrote in Lebanese.[197][198][195] Foreign works, such as La Fontaine's Fables, were translated into Lebanese using Akl's alphabet.[199] The Gospel of Mark was published in Palestinian in 1940,[200] followed by the Gospel of Matthew and the Letter of James in 1946.[201][202] The four gospels were translated in Lebanese using Akl's alphabet in 1996 by Gilbert Khalifé. Muris 'Awwad translated the four gospels and The Little Prince in 2001 in Lebanese in Arabic script.[203][195] The Little Prince was also translated into Palestinian and published in two biscriptal editions (one Arabic/Hebrew script, one Arabic/Latin script).[204][205][206]

Newspapers usually use MSA and reserve Levantine for sarcastic commentaries and caricatures.[207] Headlines in Levantine are common. The letter to the editor section often includes entire paragraphs in Levantine. Many newspapers also regularly publish personal columns in Levantine, such as خرم إبرة xurm ʾibra, lit. '[through the] needle's eye' in the weekend edition of Al-Ayyam.[208] From 1983 to 1990, Said Akl's newspaper Lebnaan was published in Lebanese written in the Latin alphabet.[209] Levantine is also commonly used in zajal and other forms of oral poetry.[210][56] Zajal written in vernacular was published in Lebanese newspapers such as Al-Mashriq ("The Levant", from 1898) and Ad-Dabbur ("The Hornet", from 1925). In the 1940s, five reviews in Beirut were dedicated exclusively to poetry in Lebanese.[195] In a 2013 study, Abuhakema investigated 270 written commercial ads in two Jordanian (Al Ghad and Ad-Dustour) and two Palestinian (Al-Quds and Al-Ayyam) daily newspapers. The study concluded that MSA is still the most used variety in ads, although both varieties are acceptable and Levantine is increasingly used.[211][212]

Most comedies are written in Levantine.[213] In Syria, plays became more common and popular in the 1980s by using Levantine instead of Classical Arabic. Saadallah Wannous, the most renowned Syrian playwright, used Syrian Arabic in his later plays.[214] Comic books, like the Syrian comic strip Kūktīl, are often written in Levantine instead of MSA.[215] In novels and short stories, most authors, such as Arab Israelis Riyad Baydas and Odeh Bisharat, write the dialogues in their Levantine dialect, while the rest of the text is in MSA.[216][217][218][194] Lebanese authors Elias Khoury (especially in his recent works) and Kahlil Gibran wrote the main narrative in Levantine.[219][220] Some collections of short stories and anthologies of Palestinian folktales (turāṯ, 'heritage literature') display full texts in dialect.[221] On the other hand, Palestinian children's literature is almost exclusively written in MSA.[222][26]

Internet users in the Arab world communicate with their dialect language (such as Levantine) more than MSA on social media (such as Twitter, Facebook, or in the comments of online newspapers). According to one study, between 12% and 23% of all dialectal Arabic content online was written in Levantine depending on the platform.[223]

Phonology

| Labial | Dental | Denti-alveolar | Post-alv./ Palatal |

Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | emphatic | |||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ||||||||

| Stop/ Affricate |

voiceless | (p)[lower-alpha 8] | t | tˤ | k | q[lower-alpha 9] | ʔ | |||

| voiced | b | d | dˤ | d͡ʒ | (ɡ)[lower-alpha 10] | |||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | θ | s | sˤ | ʃ | x ~ χ | ħ | h | |

| voiced | (v)[lower-alpha 8] | ð | z | ðˤ ~ zˤ | ɣ ~ ʁ | ʕ | ||||

| Approximant | l | (ɫ) | j | w | ||||||

| Trill | r | |||||||||

Levantine phonology is characterized by rich socio-phonetic variations along socio-cultural (gender; religion; urban, rural or Bedouin) and geographical lines.[226] For instance, in urban varieties, interdentals /θ/, /ð/, and /ðʕ/ tend to merge to stops or fricatives [t] ~ [s]; [d] ~ [z]; and [dʕ] ~ [zʕ] respectively.[227][224] The Classical Arabic voiceless uvular plosive /q/ is pronounced [q] (among Druze), [ʔ] (in most urban centers, especially Beirut, Damascus, and Jerusalem, and in Amman among women), [ɡ] (in Amman among men, in most other Jordanian dialects and in Gaza), [k] or even /kʕ/ (in rural Palestinian).[228][48][49][68]

| Arabic letter | Modern Standard Arabic | Levantine (female/urban)[224] | Levantine (male/rural) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ث | /θ/ (th) | /t/ (t) or /s/ (s) | /θ/ (th) |

| ج | /d͡ʒ/ (j) | /ʒ/ (j) | /d͡ʒ/ (j) |

| ذ | /ð/ (dh) | /d/ (d) or /z/ (z) | /ð/ (dh) |

| ض | /dˤ/ (ḍ) | /dˤ/ (ḍ) | /ðˤ/ (ẓ) |

| ظ | /ðˤ/ (ẓ) | /dˤ/ (ḍ) or /zˤ/ | /ðˤ/ (ẓ) |

| ق | /q/ (q) | /ʔ/ (ʾ) | /ɡ/ (g) |

Vowel length is phonemic in Levantine. Vowels often show dialectal or allophonic variations that are socially, geographically, and phonologically conditioned.[229] Diphthongs /aj/ and /aw/ are found in some Lebanese dialects, they respectively correspond to long vowels /eː/ and /oː/ in other dialects.[229][48][49] One of the most distinctive features of Levantine is word-final imāla, a process by which the vowel corresponding to ة tāʼ marbūṭah is raised from [a] to [æ], [ɛ], [e] or even [i] in some dialects.[230][231] The difference between the short vowel pairs e and i as well as o and u is not always phonemic.[91] The vowel quality is usually i and u in stressed syllables.[71] Vowels in word-final position are shortened. As a result, more short vowels are distinguished.[71]

In the north, stressed i and u merge. They usually become i, but might also be u near emphatic consonants. Syrians and Beirutis tend to pronounce both of them as schwa [ə].[58][232][55] The long vowel "ā" is pronounced similar to "ē" or even merges with "ē", when it is not near an emphatic or guttural consonant.[58][48]

| Short | Long | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Central | Back | Front | Back | |

| Close/High | /i/ | — | /u/ | /iː/ | /uː/ |

| Mid | /e/ | /ə/ | /o/ | /eː/ | /oː/ |

| Open/Low | /a/ [i ~ ɛ ~ æ ~ a ~ ɑ] | /aː/ [ɛː ~ æː ~ aː ~ ɑː] | |||

| Diphthongs | /aw/, /aj/ | ||||

Syllabification and phonotactics are complex, even within a single dialect.[232] Speakers often add a short vowel, called helping vowel or epenthetic vowel, sounding like a short schwa right before a word-initial consonant cluster to break it, as in ktiːr ǝmniːħ, 'very good/well'. They are not considered part of the word and are never stressed. This process of anaptyxis is subject to social and regional variation.[233][234][235][236] They are usually not written.[237] A helping vowel is inserted:

- Before the word, if this word starts with two consonants and is at the beginning of a sentence,

- Between two words, when a word ending in a consonant is followed by a word that starts with two consonants,

- Between two consonants in the same word, if this word ends with two consonants and either is followed by a consonant or is at the end of a sentence.[238][239]

In the Damascus dialect, word stress falls on the last superheavy syllable (CVːC or CVCC). In the absence of a superheavy syllable:

- if the word is bisyllabic, stress falls on the penultimate,

- if the word contains three or more syllables and none of them is superheavy, then stress falls:

- on the penultimate, if it is heavy (CVː or CVC),

- on the antepenult, if the penultimate is light (CV).[233]

Orthography and writing systems

Until recently, Levantine was rarely written. Brustad and Zuniga report that in 1988, they did not find anything published in Levantine in Syria. By the late 2010s, written Levantine was used in many public venues and on the internet,[240] especially social media.[158] There is no standard Levantine orthography.[158] There have been failed attempts to Latinize Levantine, especially Lebanese. For instance, Said Akl promoted a modified Latin alphabet. Akl used this alphabet to write books and publish a newspaper, Lebnaan.[241][242][209]

Written communication takes place using a variety of orthographies and writing systems, including Arabic (right-to-left script), Hebrew (right-to-left, used in Israel, especially online among Bedouin, Arab Christians, and Druze[9][10][11][12][13]), Latin (Arabizi, left-to-right), and a mixture of the three. Arabizi is a non-standard romanization used by Levantine speakers in social media and discussion forums, SMS messaging, and online chat.[243] Arabizi initially developed because the Arabic script was not available or not easy to use on most computers and smartphones; its usage declined after Arabic software became widespread.[244] According to a 2020 survey done in Nazareth, Arabizi "emerged" as a "'bottom-up' orthography" and there is now "a high degree of normativization or standardisation in Arabizi orthography." Among consonants, only five (ج ,ذ ,ض ,ظ ,ق) revealed variability in their Arabizi representation.[6]

A 2012 study found that on the Jordanian forum Mahjoob about one-third of messages were written in Levantine in the Arabic script, one-third in Arabizi, and one-third in English.[7] Another 2012 study found that on Facebook, the Arabic script was dominant in Syria, while the Latin script dominated in Lebanon. Both scripts were used in Palestine, Israel, and Jordan. Several factors affect script choice: formality (the Arabic script is more formal), ethnicity and religion (Muslims use the Arabic script more while Israeli Druze and Bedouins prefer Hebrew characters), age (young use Latin more), education (educated people write more in Latin), and script congruence (the tendency to reply to a post in the same script).[10]

The Arabic alphabet is always cursive, and letters vary in shape depending on their position within a word. Letters exhibit up to four distinct forms corresponding to an initial, medial (middle), final, or isolated position (IMFI).[245] Only the isolated form is shown in the tables below. In the Arabic script, short vowels are not represented by letters but by diacritics above or below the letters. When Levantine is written with the Arabic script, short vowels are usually only indicated if a word is ambiguous.[246][247] In the Arabic script, a shadda above a consonant doubles it. In Latin alphabet, the consonant is written twice: مدرِّسة, mudarrise, 'a female teacher' / مدرسة, madrase, 'a school'.[247] Said Akl's Latin alphabet uses non-standard characters.[8]

| Letter(s) | Romanization | IPA | Pronunciation notes[248][249] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cowell[250] | Al-Masri[251] | Aldrich[246] | Elihay[249] | Liddicoat[247] | Assimil[252] | Stowasser[248] | Arabizi[6][10] | |||

| أ إ ؤ ئ ء | ʔ | ʔ | ʔ | ʼ | ʻ | ʼ | ʔ | 2 or not written | [ʔ] | glottal stop like in uh-oh |

| ق | q | g | ʔ q | q q̈ | q | ʼ | q q̈ | 2 or not written 9 or q or k | [ʔ] or [g] [q] | – glottal stop (urban accent) or "hard g" as in get (Jordanian, Bedouin, Gaza[68]) - guttural "k", pronounced further back in the throat (formal MSA words) |

| ع | ε | 3 | 3 | c | ع | c | ε | 3 | [ʕ] | voiced throat sound similar to "a" as in father, but with more friction |

| ب | b | [b] | as in English | |||||||

| د | d | [d] | as in English | |||||||

| ض | ḍ | D | ɖ | ḍ | ḍ | d | ḍ | d or D | [dˤ] | emphatic "d" (constricted throat, surrounded vowels become dark) |

| ف | f | [f] | as in English | |||||||

| غ | ġ | gh | ɣ | ġ | gh | gh | ġ | 3' or 8 or gh | [ɣ] | like Spanish "g" between vowels, similar to French "r" |

| ه | h | [h] | as in English | |||||||

| ح | ḥ | H | ɧ | ḥ | ḥ | h | ḥ | 7 or h | [ħ] | "whispered h", has more friction in the throat than "h" |

| خ | x | x | x | ꜧ̄ | kh | kh | x | 7' or 5 or kh | [x] | "ch" as in Scottish loch, like German "ch" or Spanish "j" |

| ج | ž | j | ž | j or g | [dʒ] or [ʒ] | "j" as in jump or "s" as in pleasure | ||||

| ك | k | [k] | as in English | |||||||

| ل | l | [l] [ɫ] | – light "l" as in English love - dark "l" as call, used in Allah and derived words | |||||||

| م | m | [m] | as in English | |||||||

| ن | n | [n] | as in English | |||||||

| ر | r | [rˤ] [r] | – "rolled r" as in Spanish or Italian, usually emphatic - not emphatic before vowel "e" or "i" or after long vowel "i" | |||||||

| س | s | [s] | as in English | |||||||

| ث | θ | th | s | s ṯ | th | t | s t | t or s or not written | [s] [θ] | – "s" as in English (urban) - voiceless "th" as in think (rural, formal MSA words) |

| ص | ṣ | S | ʂ | ṣ | ṣ | s | ṣ | s | [sˤ] | emphatic "s" (constricted throat, surrounded vowels become dark) |

| ش | š | sh | š | š | sh | ch | š | sh or ch or $ | [ʃ] | "sh" as in sheep |

| ت | t | [t] | as in English but with the tongue touching the back of the upper teeth | |||||||

| ط | ṭ | T | ƭ | ṭ | ṭ | t | ṭ | t or T or 6 | [tˤ] | emphatic "t" (constricted throat, surrounded vowels become dark) |

| و | w | [w] | as in English | |||||||

| ي | y | [j] | as in English | |||||||

| ذ | 𝛿 | dh | z | z ḏ | d | d or z | z d | d or z or th | [z] [ð] | – "z" as in English (urban) - voiced "th" as in this (rural, formal MSA words) |

| ز | z | [z] | as in English | |||||||

| ظ | ẓ | DH | ʐ | ẓ | ẓ | z | ḍ ẓ | th or z or d | [zˤ] | emphatic "z" (constricted throat, surrounded vowels become dark) |

| Letter(s) | Aldrich[246] | Elihay[249] | Liddicoat[247] | Assimil[252] | Arabizi[6] | Environment | IPA | Pronunciation notes[248][249] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ـَ | ɑ | α | a | a | a | near emphatic consonant | [ɑ] | as in got (American pronunciation) |

| a | elsewhere | [a~æ] | as in cat | |||||

| ـِ | i | e / i | e / i / é | i / é | e | before/after ح ḥ or ع ʕ | [ɛ] | as in get |

| elsewhere | [e] or [ɪ] | as in kit | ||||||

| ـُ | u | o / u | o / u | o / ou | u | any | [o] or [ʊ] | as in full |

| ـَا | ɑ̄ | ᾱ | aa | ā | a | near emphatic consonant | [ɑː] | as in father |

| ā | elsewhere | [aː~æː] | as in can | |||||

| ē | ē | Imāla in the north | [ɛː~eː] | as in face, but plain vowel | ||||

| ـَي | ē | ee | e | any | [eː] | |||

| ɑy | in open syllable in Lebanese | /aj/ | as in price or in face | |||||

| ـِي | ī | ii | ī | any | [iː] | as in see | ||

| ـَو | ō | ō | oo | ō | o | any | [oː] | as in boat, but plain vowel |

| ɑw | in open syllable in Lebanese | /aw/ | as in mouth or in boat | |||||

| ـُو | ū | uu | oū | any | [uː] | as in food | ||

| ـَا ـَى ـَة | ɑ | α | a | a | a | near emphatic consonant | [ɑ] | as in got (American pronunciation) |

| a | elsewhere | [a~æ] | as in cat | |||||

| ـَا ـَى | i (respelled to ي) | — | é | é/i/e | Imāla in the north | [ɛ~e] | as in get, but closed vowel | |

| ـِة | i | e | e | any | [e] | |||

| ـِي | i | i | any | [i] [e] (Lebanese) | as in see, but shorter merged to "e" in Lebanese | |||

| ـُه | u (respelled to و) | o | — | o | o/u | any | [o] | as in lot, but closed vowel |

| ـُو | u | any | [u] [o] (Lebanese) | as in food, but shorter merged to "o" in Lebanese | ||||

Grammar

VSO and SVO word orders are possible in Levantine. In both cases, the verb precedes the object.[253] SVO is more common in Levantine, while Classical Arabic prefers VSO.[254] Subject-initial order indicates topic-prominent sentences, while verb-initial order indicates subject-prominent sentences.[255] In interrogative sentences, the interrogative particle comes first.[256]

Nouns and noun phrases

Nouns are either masculine or feminine and singular, dual or plural.[257][258] The dual is formed with the suffix ين- -ēn.[259][258] Most feminine singular nouns end with ـة tāʼ marbūṭah, pronounced as –a or -e depending on the preceding consonant: -a after guttural (ح خ ع غ ق ه ء) and emphatic consonants (ر ص ض ط ظ), -e after other consonants.[71] Unlike Classical Arabic, Levantine has no case marking.[258]

Levantine has a definite article, which marks common nouns (i.e. nouns that are not proper nouns) as definite. Its absence marks common nouns as indefinite. [260] The Arabic definite article ال il precedes the noun or adjective and has multiple pronunciations. Its vowel is dropped when the preceding word ends in a vowel. A helping vowel "e" is inserted if the following word begins with a consonant cluster.[238] It assimilates with "sun letters" (consonants that are pronounced with the tip of the tongue).[238] The letter Jeem (ج) is a sun letter for speakers pronouncing it as [ʒ] but not for those pronouncing it as [d͡ʒ].[260][261]

For nouns referring to humans, the regular (also called sound) masculine plural is formed with the suffix -īn. The regular feminine plural is formed with -āt.[71][262] The masculine plural is used to refer to a group with both genders.[263] There are many broken plurals (also called internal plurals), in which the consonantal root of the singular is changed.[258] These plural patterns are shared with other varieties of Arabic and may also be applied to foreign borrowings.[258] Several patterns of broken plurals exist, and it is impossible to predict them exactly.[264] One common pattern is for instance CvCvC => CuCaCa (e.g.: singular: مدير mudīr, 'manager'; plural: مدرا mudara, 'managers').[264] Inanimate objects take feminine singular agreement in the plural, for verbs, attached pronouns, and adjectives.[265]

The genitive is formed by putting the nouns next to each other[266] in a construct called iḍāfah, lit. 'addition'. The first noun is always indefinite. If an indefinite noun is added to a definite noun, it results in a new definite compound noun:[267][71][268] كتاب الإستاذ ktāb il-ʾistāz ⓘ, 'the book of the teacher'.[269] Besides possessiveness, the iḍāfah can also specify or define the first term.[267] Although there is no limit to the number of nouns in an iḍāfah, it is rare to have three or more.[266] The first term must be in the construct state: if it ends in the feminine marker (/-ah/, or /-ih/), it changes to (/-at/, /-it/) in pronunciation (i.e. ة pronounced as /t/): مدينة نيويورك madīnet nyū-yōrk ⓘ, 'New York City'.[267]

Adjectives typically have three forms: a masculine singular, a feminine singular, and a plural.[71] In most adjectives, the feminine is formed through the addition of -a/e.[270][228] Many adjectives have the pattern فعيل (fʕīl / CCīC or faʕīl / CaCīC), but other patterns exist.[71] Adjectives derived from nouns using the suffix ـي -i are called nisba adjectives. Their feminine form ends in ـية -iyye and their plural in ـيين -iyyīn.[271] Nouns in dual have adjectives in plural.[71] The plural of adjectives is either regular ending in ـين -īn or is an irregular "broken" plural. It is used with nouns referring to people. For non-human, inanimate, or abstract nouns, adjectives use either the plural or the singular feminine form regardless of gender.[71][272][265]

Adjectives follow the noun they modify and agree with it in definiteness. Adjectives without an article after a definite noun express a clause with the invisible copula "to be":[273]

- بيت كبير bēt kbīr ⓘ, 'a big house'

- البيت الكبير il-bēt le-kbīr ⓘ, 'the big house'

- البيت كبير il-bēt kbīr ⓘ, 'the house is big'

The elative is used for comparison, instead of separate comparative and superlative forms.[274] The elative is formed by adding a hamza at the beginning of the adjective and replacing the vowels by "a" (pattern: أفعل ʾafʕal / aCCaC, e.g.: كبير kbīr, 'big'; أكبر ʾakbar, 'bigger/biggest').[71] Adjective endings in ي (i) and و (u) are changed into ی (a). If the second and third consonant in the root are the same, they are geminated (pattern: أفلّ ʾafall / ʾaCaCC).[275] When an elative modifies a noun, it precedes the noun, and no definite article is used.[276]

Levantine does not distinguish between adverbs and adjectives in adverbial function. Almost any adjective can be used as an adverb: منيح mnīḥ, 'good' vs. نمتي منيح؟ nimti mnīḥ? ⓘ, 'Did you sleep well?'. MSA adverbs, with the suffix -an, are often used, e.g., أبدا ʾabadan, 'at all'.[255] Adverbs often appear after the verb or the adjective. كتير ktīr, 'very' can be positioned after or before the adjective.[255] Adverbs of manner can usually be formed using bi- followed by the nominal form: بسرعة b-sirʿa, 'fast, quickly', lit. 'with speed'.[58]

مش miš or in Syrian Arabic مو mū negate adjectives (including active participles), demonstratives, and nominal phrases:[277][278]

- أنا مش فلسطيني. ʾana miš falasṭīni. ⓘ, 'I'm not Palestinian.'

- مش عارفة. miš ʕārfe. ⓘ, 'She doesn't know.'

- هادا مش منيح. hāda miš mnīḥ. ⓘ / هاد مو منيح. hād mū mnīḥ., 'That's not good.'

Pronouns

Levantine has eight persons and eight pronouns. Contrary to MSA, dual pronouns do not exist in Levantine; the plural is used instead. Because conjugated verbs indicate the subject with a prefix or a suffix, independent subject pronouns are usually unnecessary and mainly used for emphasis.[279][280] Feminine plural forms modifying human females are found primarily in rural and Bedouin areas. They are not mentioned below.[281]

| Singular | Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person (m./f.) | أنا ʾana | احنا ʾiḥna (South) / نحنا niḥna (North) | |

| 2nd person | m. | انت ʾinta | انتو / انتوا ʾintu |

| f. | انتي ʾinti | ||

| 3rd person | m. | هو huwwe | هم humme (South) / هن hinne (North) |

| f. | هي hiyye | ||

Direct object pronouns are indicated by suffixes attached to the conjugated verb. Their form depends on whether the verb ends with a consonant or a vowel. Suffixed to nouns, these pronouns express possessive.[282][280] Levantine does not have the verb "to have". Instead, possession is expressed using the prepositions عند ʕind, lit. 'at' (meaning "to possess") and مع maʕ, lit. 'with' (meaning "to have on oneself"), followed by personal pronoun suffixes.[283][284]

| Singular | Plural | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| after consonant | after vowel | |||

| 1st person | after verb | ـني -ni | ـنا -na | |

| else | ـِي -i | ـي -y | ||

| 2nd person | m. | ـَك -ak | ـك -k | ـكُن -kun (North) ـكُم -kom ـكو -ku (South) |

| f. | ـِك -ik | ـكِ -ki | ||

| 3rd person | m. | و -u (North) ـُه -o (South) |

ـه (silent)[lower-alpha 11] | ـُن -(h/w/y)un (North) ـهُم -hom (South) |

| f. | ـا -a (North) ـها -ha (South) |

ـا -(h/w/y)a (North) ـها -ha (South) | ||

Indirect object pronouns (dative) are suffixed to the conjugated verb. They are formed by adding an ل (-l) and then the possessive suffix to the verb.[281] They precede object pronouns if present:[281]

- جاب الجريدة لأبوي jāb il-jarīde la-ʔabūy ⓘ, 'he brought the newspaper to my father',

- جابها لأبوي jāb-ha la-ʔabūy ⓘ, 'he brought it to my father',

- جابله الجريدة jab-lo il-jarīde ⓘ, 'he brought him the newspaper',

- جابله ياها jab-lo yyā-ha ⓘ, 'he brought it to him'.[285]

| Singular | Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person (m./f.) | ـلي -li | ـلنا -lna | |

| 2nd person | m. | لَك -lak | ـلكُن -lkun (North) ـلكُم -lkom, ـلكو -lku (South) |

| f. | ـِلك -lik | ||

| 3rd person | m. | لو -lu (North) لُه -lo (South) |

ـلُن -lun (North) ـلهُم -lhom (South) |

| f. | ـلا -la (North) ـلها -lha (South) | ||

Demonstrative pronouns have three referential types: immediate, proximal, and distal. The distinction between proximal and distal demonstratives is of physical, temporal, or metaphorical distance. The genderless and numberless immediate demonstrative article ها ha is translated by "this/the", to designate something immediately visible or accessible.[286]

| Singular | Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Proximal (this, these) |

m. | هادا hāda / هاد hād (South, Syria) هيدا hayda (Lebanon) |

هدول hadōl (South, Syria) هيدول haydōl / هودي hawdi (Lebanon) |

| f. | هادي hādi / هاي hāy (South) هيّ hayy (Syria) هيدي haydi (Lebanon) | ||

| Distal (that, those) |

m. | هداك hadāk (South, Syria) هيداك haydāk (Lebanon) |

هدولاك hadōlāk (South) هدوليك hadōlīk (Syria) هيدوليك haydōlīk (Lebanon) |

| f. | هديك hadīk (South, Syria) هيديك haydīk (Lebanon) | ||

Root and verb forms

Most Levantine verbs are based on a triliteral root (also called radical or Semitic root) made of three consonants. The set of consonants communicates the basic meaning of a verb, e.g. ك ت ب k-t-b ('write'), ق ر ء q-r-ʼ ('read'), ء ك ل ʼ-k-l ('eat'). Changes to the vowels in between the consonants, along with prefixes or suffixes, specify grammatical functions such as tense, person, and number, in addition to changes in the meaning of the verb that embody grammatical concepts such as mood (e.g., indicative, subjunctive, imperative), voice (active or passive), and functions such as causative, intensive, or reflexive.[289] Quadriliteral roots are less common but often used to coin new vocabulary or Arabicize foreign words.[290][291] The base form is the third-person masculine singular of the perfect (also called past) tense.[292]

Almost all Levantine verbs belong to one of ten verb forms (also called verb measures,[293] stems,[294] patterns,[295] or types[296]). Form I, the most common one, serves as a base for the other nine forms. Each form carries a different verbal idea relative to the meaning of its root. Technically, ten verbs can be constructed from any given triconsonantal root, although not all of these forms are used.[289] After Form I, Forms II, V, VII, and X are the most common.[294] Some irregular verbs do not fit into any of the verb forms.[293]

In addition to its form, each verb has a "quality":

- Sound (or regular): 3 distinct radicals, neither the second nor the third is 'w' or 'y',

- Verbs containing the radicals 'w' or 'y' are called weak. They are either:

- Hollow: verbs with 'w' or 'y' as the second radical, which becomes a long 'a' in some forms, or

- Defective: verbs with 'w' or 'y' as the third radical, treated as a vowel,

- Geminate (or doubled): the second and third radicals are identical, remaining together as a double consonant.[293]

Regular verb conjugation

The Levantine verb has only two tenses: past (perfect) and present (also called imperfect, b-imperfect, or bi-imperfect). The present tense is formed by adding the prefix b- or m- to the verb root. The future tense is an extension of the present tense. The negative imperative is the same as the negative present with helping verb (imperfect). Various prefixes and suffixes designate the grammatical person and number as well as the mood. The following table shows the paradigm of a sound Form I verb, كتب katab, 'to write'.[289] There is no copula in the present tense in Levantine. In other tenses, the verb كان kān is used. Its present tense form is used in the future tense.[297]

The b-imperfect is usually used for the indicative mood (non-past present, habitual/general present, narrative present, planned future actions, or potential). The prefix b- is deleted in the subjunctive mood, usually after modal verbs, auxiliary verbs, pseudo-verbs, prepositions, and particles.[71][91][58][225] The future can also be expressed by the imperfect preceded by the particle رح raḥ or by the prefixed particle حـ ḥa-.[298] The present continuous is formed with the progressive particle عم ʕam followed by the imperfect, with or without the initial b/m depending on the speaker.[299]

The active participle, also called present participle, is grammatically an adjective derived from a verb. Depending on the context, it can express the present or present continuous (with verbs of motion, location, or mental state), the near future, or the present perfect (past action with a present result).[300] It can also serve as a noun or an adjective.[301] The passive participle, also called past participle,[14] has a similar meaning as in English (i.e., sent, written). It is mainly used as an adjective and sometimes as a noun. It is inflected from the verb based on its verb form.[302] However, passive participles are largely limited to verb forms I (CvCvC) and II (CvCCvC), becoming maCCūC for the former and mCaCCaC for the latter.[255]

| Singular | Dual/Plural | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person | 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person | ||

| Past[lower-alpha 13] | m. | -it | -it | ∅ (base form) | -na | -tu | -u |

| f. | -ti | -it (North) -at (South) | |||||

| Present[lower-alpha 14] | m. | bi- (North) ba- (South) |

bti- | byi- (North) bi- (South) |

mni- | bti- -u | byi- -u (North) bi- -u (South) |

| f. | bti- -i | bti- | |||||

| Present with helping verb[lower-alpha 15] | m. | i- (North) a- (South) |

ti- | yi- | ni- | ti- -u | yi- -u |

| f. | ti- -i | ti- | |||||

| Positive imperative[lower-alpha 16] | m. | — | ∅ (Lengthening the present tense vowel, North) i- (Subjunctive without initial consonant, South) |

— | — | -u (Stressed vowel u becomes i, North) i- -u (South) |

— |

| f. | -i (Stressed vowel u becomes i, North) i- -i (South) | ||||||

| Active participle[lower-alpha 17] | m. | -ē- (North) or -ā- (South) after the first consonant | -īn (added to the masculine form) | ||||

| f. | -e/i or -a (added to the masculine form) | ||||||

| Passive participle[lower-alpha 18] | m. | ma- and -ū- after the second consonant | |||||

| f. | -a (added to the masculine form) | ||||||

Compound tenses

The verb كان kān, followed by another verb, forms compound tenses. Both verbs are conjugated with their subject.[305]

| kān in the past tense | kān in the present tense | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Followed by | Levantine | English | Levantine | English |

| Past tense | كان عمل kān ʕimel | he had done | بكون عمل bikūn ʕimel | he will have done |

| Active participle | كان عامل kān ʕāmel | he had done | بكون عامل bikūn ʕāmel | he will have done |

| Subjunctive | كان يعمل kān yiʕmel | he used to do / he was doing | بكون يعمل bikūn yiʕmel | he will be doing |

| Progressive | كان عم يعمل kān ʕam yiʕmel | he was doing | بكون عم يعمل bikūn ʕam yiʕmel | he will be doing |

| Future tense | كان رح يعمل kān raḥ yiʕmel كان حيعمل kān ḥa-yiʕmel | he was going to do | — | |

| Present tense | كان بعمل kān biʕmel | he would do | ||

Passive voice

Form I verbs often correspond to an equivalent passive form VII verb, with the prefix n-. Form II and form III verbs usually correspond to an equivalent passive in forms V and VI, respectively, with the prefix t-.[293] While the verb forms V, VI and VII are common in the simple past and compound tenses, the passive participle (past participle) is preferred in the present tense.[307]

| Active | Passive | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verb form | Levantine | English | Verb form | Levantine | English |

| I | مسك masak | to catch | VII | انمسك inmasak | to be caught |

| II | غيّر ḡayyar | to change | V | تغيّر tḡayyar | to be changed |

| III | فاجأ fājaʾ | to surprise | VI | تفاجأ tfājaʾ | to be surprised |

Negation

Verbs and prepositional phrases are negated by the particle ما mā / ma either on its own or, in the south, together with the suffix ـش -iš at the end of the verb or prepositional phrase. In Palestinian, it is also common to negate verbs by the suffix ـش -iš only.[278]

| Without -š | With -š | English | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levantine (Arabic) | Levantine (Latin) | Levantine (Arabic) | Levantine (Latin) | |

| ما كتب. | mā katab. ⓘ | ما كتبش. | ma katab-š. ⓘ | He didn't write. |

| ما بحكي إنكليزي. | mā baḥki ʾinglīzi. ⓘ | ما بحكيش إنكليزي. | ma baḥkī-š ʾinglīzi. ⓘ | I don't speak English. |

| ما تنسى! | mā tinsa! ⓘ | ما تنساش! | ma tinsā-š! ⓘ | Don't forget! |

| ما بده ييجي عالحفلة. | mā biddo yīji ʕa-l-ḥafle. ⓘ | — | He doesn't want to come to the party. | |

Vocabulary

The lexicon of Levantine is overwhelmingly Arabic,[148] and a large number of Levantine words are shared with at least another vernacular Arabic variety outside the Levant, especially with Egyptian.[308] Many words, such as verbal nouns (also called gerunds or masdar[14]), are derived from a Semitic root. For instance, درس dars, 'a lesson' is derived from درس daras, 'to study, to learn'.[309] Levantine also includes layers of ancient languages: Aramaic (mainly Western Aramaic), Canaanite, classical Hebrew (Biblical and Mishnaic), Persian, Greek, and Latin.[310]

Aramaic influence is significant, especially in vocabulary and in rural areas. Aramaic words underwent morphophonemic adaptation when they entered Levantine. Over time, it has become difficult to identify them. They belong to different fields of everyday life such as seasonal agriculture, housekeeping, tools and utensils, and Christian religious terms.[310][311] Aramaic is still spoken in the Syrian villages of Maaloula, al-Sarkha, and Jubb'adin;[135] near them, Aramaic borrowings are more frequent.[131][312]

Since the early modern period, Levantine has borrowed from Turkish and European languages, mainly English (particularly in technology and entertainment[313]), French (especially in Lebanese due to the French Mandate[94]), German, and Italian.[310] Modern Hebrew significantly influences the Palestinian dialect spoken by Arab Israelis.[151][314] Loanwords are gradually replaced with words of Arabic root. For instance, borrowings from Ottoman Turkish that were common in the 20th century have been largely replaced by Arabic words after the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire.[148] Arabic-speaking minorities in Turkey (mainly in Hatay) are still influenced by Turkish.[146][147]

With about 50% of common words, Levantine (especially Palestinian) is the closest colloquial variety to MSA in terms of lexical similarity.[315][4][16] In the vocabulary of five-year-old native Palestinians: 40% of the words are not present in MSA, 40% are related to MSA but phonologically different (sound change, addition, or deletion), and 20% are identical to MSA.[316] In terms of morphemes, 20% are identical between MSA and Palestinian Arabic, 30% are strongly overlapping (slightly different forms, same function), 20% are partially overlapping (different forms, same function), and 30% are unique to Palestinian Arabic.[317]

Sample text

| Lebanese (Arabic)[318] | Lebanese (Romanized)[318] | Palestinian (Arabic)[lower-alpha 19][319][206] | Palestinian (Romanized)[lower-alpha 20][319][206] | MSA[320] | MSA (Romanized)[320] | English[321] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

الأمير الزغير | l amir l z8ir | الأمير الصغير | il-ʼamir le-zġīr | الأمير الصغير | Al-amīr al-ṣaghīr | The Little Prince |

وهيك يا إميري الزغير، | w hek, ya amire l z8ir, | أخ، يا أميري الصغير! | ʼᾱꜧ̄, yā ʼamīri le-zġīr! | آه أيها الأمير الصغير ، | Āh ayyuhā al-amīr al-ṣaghīr, | Oh, little prince! |

ونتفي نتفي، فهمت حياتك المتواضعة الكئيبي. | w netfe netfe, fhemet 7ayetak l metwad3a l ka2ibe. | شوي شوي عرفت عن سر حياتك الكئبة. | šwayy ešwayy eCrifet Can sirr ḥayātak il-kaʼībe. | لقد أدركت شيئا فشيئا أبعاد حياتك الصغيرة المحزنة ، | laqad adrakat shayʼan fashaiʼā abʻād ḥayātik al-ṣaghīrah almuhzinat, | Bit by bit I came to understand the secrets of your sad little life. |

إنت يلّلي ضلّيت عَ مِدّة طويلي ما عندك شي يسلّيك إلاّ عزوبة التطليع بغياب الشمس. | enta yalli dallet 3a medde tawile ma 3andak shi ysallik illa 3uzubet l tutli3 bi 8iyeb l shames. | وما كانش إلك ملاذ تاني غير غروب الشمس. | u-ma kan-š ʼilak malād tāni ġēr ġurūb iš-šams. | لم تكن تملك من الوقت للتفكير والتأمل غير تلك اللحظات التي كنت تسرح فيها مع غروب الشمس. | lam takun tamalluk min al-waqt lil-tafkīr wa-al-taʼammul ghayr tilka al-laḥaẓāt allatī kuntu tasrah fīhā maʻa ghurūb al-shams. | For a long time you had found your only entertainment in the quiet pleasure of looking at the sunset. |

هالشي الجزئي، وجديد، عرفتو رابع يوم من عبكرا، لِمّن قلتلّي: | hal shi ljez2e, w jdid, 3arefto rabe3 yom men 3abokra, lamman eltelle: | وهدا الإشي عرفته بصباح اليوم الرابع لما قلت لي: | u-hāda l-ʼiši Crifto bi-ṣαbᾱḥ il-yōm ir-rᾱbeC lamma qultelli: | لقد عرفت بهذا الأمر الجديد في صباح اليوم الرابع من لقائنا، عندما قلت لي: | Laqad ʻaraftu bi-hādhā al-amīr al-jadīd fī ṣabāḥ al-yawm al-rābiʻ min liqāʼnā, ʻindamā qultu lī: | I learned that new detail on the morning of the fourth day, when you said to me: |

أنا بحب غياب الشمس. | ana b7eb 8yeb l shames. | – بحب كتير غروب الشمس. | – baḥebb ektīr ġurūb iš-šams. | إنني مغرم بغروب الشمس. | Innanī mughram bighuruwb al-shams. | I am very fond of sunsets. |

Notes

- Also known as Greater Syria.[1][2]

- In a broader meaning, "Eastern Arabic" refers to Mashriqi Arabic, to which Levantine belongs, one of the two main varieties of Arabic, as opposed to Western Arabic, also called Maghrebi Arabic.[18]

- Native speakers of Arabic generally do not distinguish between Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) and Classical Arabic and refer to both as العربية الفصحى al-ʻArabīyah al-Fuṣḥā, lit. 'the eloquent Arabic'.[25]

- Ethnologue classifies Cypriot Arabic as a hybrid language between Levantine and North Mesopotamian.[53] Pr. Jonathan Owens classifies it in North Mesopotamian Arabic.[54]

- Most Christian and Muslim Lebanese people in Israel do not consider themselves Arabs, claiming to be Phoenicians.[88][89]

- Only countries with at least 100,000 speakers are shown.

- Youth, especially teenagers, are considered the most active initiators of language change.[156]

- In loanwords only.

- Mainly in words from Classical Arabic and in Druze, rural, and Bedouin dialects.

- Only in loanwords, except in Jordanian Arabic.

- The accent moves to the last vowel.

- Depending on regions and accents, the -u can be pronounced -o and the -i can be pronounced -é.[304]

- Also called perfect.

- Also called bi-imperfect, b-imperfect, or standard imperfect.

- Also called Ø-imperfect, imperfect, or subjunctive.

- Also called imperative or command.

- Also called present participle. Not all active participles are used and their meaning varies.

- Also called past participle, mostly used as an adjective. Not all passive participles are used and their meaning varies.

- According to the authors: "we decided to adopt a flexible approach and use a form of transcription that reflects the spelling used by native Arabic speakers when they write brief colloquial texts on computer, table or smartphone."

- Transcription follows Elihay's convention.

References

- Stowasser 2004, p. xiii.

- Cowell 1964, pp. vii–x.

- Al-Wer 2006, pp. 1920–1921.

- Levantine Arabic at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023)

- "Glottolog 4.6 – Levantine Arabic". glottolog.org. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- Abu-Liel, Aula Khatteb; Eviatar, Zohar; Nir, Bracha (2019). "Writing between languages: the case of Arabizi". Writing Systems Research. Informa. 11 (2): 1, 5, 8. doi:10.1080/17586801.2020.1814482. S2CID 222110971.

- Bianchi, Robert Michael (2012). "3arabizi – When Local Arabic Meets Global English". Acta Linguistica Asiatica. University of Ljubljana. 2 (1): 97. doi:10.4312/ala.2.1.89-100. S2CID 59056130.

- Płonka 2006, pp. 465–466.

- Shachmon & Mack 2019, p. 347.

- Abu Elhija, Dua'a (2014). "A new writing system? Developing orthographies for writing Arabic dialects in electronic media". Writing Systems Research. Informa. 6 (2): 193, 208. doi:10.1080/17586801.2013.868334. S2CID 219568845.

- Shachmon 2017, p. 89.

- Gaash, Amir (2016). "Colloquial Arabic written in Hebrew characters on Israeli websites by Druzes (and other non-Jews)". Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam. Hebrew University of Jerusalem (43–44): 15. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- Shachmon, Ori; Mack, Merav (2016). "Speaking Arabic, Writing Hebrew. Linguistic Transitions in Christian Arab Communities in Israel". Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes. University of Vienna. 106: 223–224. JSTOR 26449346.

- Aldrich 2017, p. ii.

- Al-Wer 2006, pp. 1917–1918.

- Kwaik, Kathrein Abu; Saad, Motaz; Chatzikyriakidis, Stergios; Dobnika, Simon (2018). "A Lexical Distance Study of Arabic Dialects". Procedia Computer Science. Elsevier. 142: 2. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2018.10.456.

- "1: AFRO-ASIAN phylosector" (PDF). Linguasphere. 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- Al‐Wer & Jong 2017, p. 527.

- Rice, Frank A.; Majed, F. Sa'id (2011). Eastern Arabic. Georgetown University Press. pp. xxi–xxiii. ISBN 978-1-58901-899-0. OCLC 774911149. Archived from the original on 11 July 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- Garbell, Irene (1 August 1958). "Remarks on the Historical Phonology of an East Mediterranean Arabic Dialect". WORD. 14 (2–3): 305–306. doi:10.1080/00437956.1958.11659673. ISSN 0043-7956.

- Versteegh 2014, p. 197.

- Palva, Heikki (2011). "Dialects: Classification". In Edzard, Lutz; de Jong, Rudolf (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Brill. doi:10.1163/1570-6699_eall_EALL_COM_0087.

- Al-Wer 2006, p. 1917.

- Brustad & Zuniga 2019, p. 403.

- Badawi, El-Said M. (1996). Understanding Arabic: Essays in Contemporary Arabic Linguistics in Honor of El-Said Badawi. American University in Cairo Press. p. 105. ISBN 977-424-372-2. OCLC 35163083.

- Shendy, Riham (2019). "The Limitations of Reading to Young Children in Literary Arabic: The Unspoken Struggle with Arabic Diglossia". Theory and Practice in Language Studies. Academy Publication. 9 (2): 123. doi:10.17507/tpls.0902.01. S2CID 150474487.

- Eisele, John C. (2011). "Slang". In Edzard, Lutz; de Jong, Rudolf (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Brill. doi:10.1163/1570-6699_eall_eall_com_0310.

- Liddicoat, Lennane & Abdul Rahim 2018, p. I.

- al-Sharkawi, Muhammad (2010). The Ecology of Arabic – A Study of Arabicization. Brill. p. 32. ISBN 978-90-04-19174-7. OCLC 741613187.

- Shachmon & Mack 2019, p. 362.

- Shoup, John Austin (2008). Culture and Customs of Syria. Greenwood Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-313-34456-5. OCLC 183179547.

- Płonka 2006, p. 433.

- Versteegh 2014, p. 18.

- Birnstiel 2019, pp. 367–369.

- Holes, Clive, ed. (2018). "Introduction". Arabic Historical Dialectology: Linguistic and Sociolinguistic Approaches. Oxford Studies in Diachronic and Historical Linguistics. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 5. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198701378.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-870137-8. OCLC 1055869930. Archived from the original on 19 May 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- Birnstiel 2019, p. 368.

- Al-Jallad, Ahmad (2021). "Connecting the Lines between Old (Epigraphic) Arabic and the Modern Vernaculars". Languages. 6 (4): 1. doi:10.3390/languages6040173. ISSN 2226-471X.

- Versteegh 2014, p. 172.

- Al-Jallad 2020a, p. 8.

- Huehnergard, John (2017). "Arabic in Its Semitic Context". In Al-Jallad, Ahmad (ed.). Arabic in Context: Celebrating 400 Years of Arabic at Leiden University. Brill. p. 13. doi:10.1163/9789004343047_002. ISBN 978-90-04-34304-7. OCLC 967854618.

- "apc | ISO 639-3". SIL International. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- Versteegh 2014, p. 189.

- Versteegh 2014, p. 133.

- International Phonetic Association (1999). Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A Guide to the Use of the International Phonetic Alphabet. Cambridge University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-521-65236-0. OCLC 40305532.

- Trentman, Emma; Shiri, Sonia (2020). "The Mutual Intelligibility of Arabic Dialects: Implications for the classroom". Critical Multilingualism Studies. University of Arizona. 8 (1): 116, 121. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- Schmitt 2020, p. 1391.

- "Turkey". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 16 July 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- Versteegh 2014, p. 198.

- Al‐Wer & Jong 2017, p. 531.

- "Jordan and Syria". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 30 July 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- "Egypt and Libya". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

- Versteegh 2014, p. 184.

- Borg, Alexander (2011). "Cypriot Maronite Arabic". In Edzard, Lutz; de Jong, Rudolf (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Brill. doi:10.1163/1570-6699_eall_EALL_COM_0076.

- Owens, Jonathan (2006). A Linguistic History of Arabic. OUP Oxford. p. 274. ISBN 0-19-929082-2. OCLC 62532502.

- Versteegh 2014, p. 199.

- Behnstedt, Peter (2011). "Syria". In Edzard, Lutz; de Jong, Rudolf (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Brill. doi:10.1163/1570-6699_eall_EALL_COM_0330.

- Wardini, Elie (2011). "Lebanon". In Edzard, Lutz; de Jong, Rudolf (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Brill. doi:10.1163/1570-6699_eall_SIM_001001.

- Naïm, Samia (2011). "Beirut Arabic". In Edzard, Lutz; de Jong, Rudolf (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Brill. doi:10.1163/1570-6699_eall_EALL_COM_0039.

- Arnold, Werner (2011). "Antiochia Arabic". In Edzard, Lutz; de Jong, Rudolf (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Brill. doi:10.1163/1570-6699_eall_EALL_COM_0018.

- Procházka, Stephan (2011). "Cilician Arabic". In Edzard, Lutz; de Jong, Rudolf (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Brill. doi:10.1163/1570-6699_eall_EALL_COM_0056.

- Behnstedt, Peter; Woidich, Manfred (2005). Arabische Dialektgeographie : Eine Einführung (in German). Boston: Brill. pp. 102–103. ISBN 90-04-14130-8. OCLC 182530188.

- Jong, Rudolf Erik de (2011). A Grammar of the Bedouin Dialects of Central and Southern Sinai. Brill. pp. 10, 19, 285. ISBN 978-90-04-20146-0. OCLC 727944814.

- Al-Jallad, Ahmad (2012). Ancient Levantine Arabic: A Reconstruction Based on the Earliest Sources and the Modern Dialects (PhD thesis). Harvard University. p. 212. ISBN 978-1-267-44507-0. OCLC 5828687139. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021 – via ProQuest.

- Jdetawy, Loae Fakhri (2020). "Readings in the Jordanian Arabic dialectology". Technium Social Sciences Journal. Technium Science. 12 (1): 416. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- Al-Wer, Enam (2020). "New-dialect formation: The Amman dialect". In Lucas, Christopher; Manfredi, Stefano (eds.). Arabic and contact-induced change. Language Science Press. pp. 551–552, 555. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3744549. ISBN 978-3-96110-251-8. OCLC 1164638334. Archived from the original on 11 May 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- Shahin, Kimary N. (2011). "Palestinian Arabic". In Edzard, Lutz; de Jong, Rudolf (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Brill. doi:10.1163/1570-6699_eall_EALL_COM_vol3_0247.

- Horesh, Uri; Cotter, William (2011). "Sociolinguistics of Palestinian Arabic". In Edzard, Lutz; de Jong, Rudolf (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Brill. doi:10.1163/1570-6699_eall_SIM_001007.

- Cotter, William M. (2020). "The Arabic dialect of Gaza City". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. Cambridge University Press. 52: 124, 128. doi:10.1017/S0025100320000134. S2CID 234436324.

- Prochazka 2018, p. 257.

- Smith-Kocamahhul, Joan (2011). "Turkey". In Edzard, Lutz; de Jong, Rudolf (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Brill. doi:10.1163/1570-6699_eall_EALL_COM_0357.

- Lentin, Jérôme (2011). "Damascus Arabic". In Edzard, Lutz; de Jong, Rudolf (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Brill. doi:10.1163/1570-6699_eall_EALL_COM_0077.

- Al‐Wer & Jong 2017, p. 529.

- Germanos, Marie-Aimée (2011). "Linguistic Representations and Dialect Contact: Some Comments on the Evolution of Five Regional Variants in Beirut". Langage et société. Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l'homme. 138 (4): IV, XIV. doi:10.3917/ls.138.0043. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- Prochazka 2018, p. 290.

- Berlinches Ramos, Carmen (2020). "Notes on Language Change and Standardization in Damascus Arabic". Anaquel de Estudios Árabes. Complutense University of Madrid. 31: 97–98. doi:10.5209/anqe.66210. S2CID 225608465. Archived from the original on 16 March 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- Al-wer, Enam; Horesh, Uri; Herin, Bruno; Fanis, Maria (2015). Uri Horesh, Bruno Herin, Maria Fanis. "How Arabic Regional Features Become Sectarian Features Jordan as a Case Study". Zeitschrift für Arabische Linguistik (62): 68–87. ISSN 0170-026X. JSTOR 10.13173/zeitarabling.62.0068.

- "Samaritans". Minority Rights Group International. 19 June 2015. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- Al-Wer 2006, p. 1921.

- Sawaie, Mohammed (2011). "Jordan". In Edzard, Lutz; de Jong, Rudolf (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Brill. doi:10.1163/1570-6699_eall_EALL_COM_vol2_0064.

- Al-Khatib, Mahmoud A. (2001). "Language shift among the Armenians of Jordan". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. De Gruyter. 2001 (152): 153. doi:10.1515/ijsl.2001.053.

- Shafrir, Asher (2011). "Ethnic minority languages in Israel" (PDF). Proceedings of the Scientific Conference AFASES. AFASES. Brasov. pp. 493, 496. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- "Syria – World Directory of Minorities & Indigenous Peoples". Minority Rights Group International. 19 June 2015. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- Orhan, Oytun (9 February 2010). "The Forgotten Turks: Turkmens of Lebanon". Center for Middle Eastern Strategic Studies. Archived from the original on 27 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- Kawtharani, Farah W.; Meho, Lokman I. (2005). "The Kurdish community in Lebanon". International Journal of Kurdish Studies. Kurdish Library. 19 (1–2): 137. Gale A135732900.

- Kadi, Samar (18 March 2016). "Armenians, Kurds in Lebanon hold on to their languages". The Arab Weekly. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- Heruti-Sover, Tali (26 October 2016). "Jerusalem's Gypsies: The Community With the Lowest Social Standing in Israel". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- Matras, Yaron (1999). "The State of Present-Day Domari in Jerusalem". Mediterranean Language Review. Harrassowitz Verlag. 11: 10. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.695.691. Archived from the original on 16 March 2022. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- Shachmon & Mack 2019, pp. 361–362.

- Lerner, Davide (22 May 2020). "These Young Israelis Were Born in Lebanon – but Don't Call Them Arabs". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 17 October 2021. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- Kossaify, Ephrem; Zeidan, Nagi (14 September 2020). "Minority report: The Jews of Lebanon". Arab News. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- Rosenhouse, Judith (2011). "Jerusalem Arabic". In Edzard, Lutz; de Jong, Rudolf (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Brill. doi:10.1163/1570-6699_eall_EALL_COM_vol2_0063.

- Sabar, Yona (2000). "Review of Jewish Life in Arabic Language and Jerusalem Arabic in Communal Perspective, A Lexico-Semantic Study. Studies in Semitic Languages and Linguistics, vol. 30". Al-'Arabiyya. Georgetown University Press. 33: 111–113. JSTOR 43195505.

- Matras, Yaron (2011). "Gypsy Arabic". In Edzard, Lutz; de Jong, Rudolf (eds.). Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Brill. doi:10.1163/1570-6699_eall_EALL_SIM_vol2_0011.

- Al-Wer 2006, p. 1920.

- Collelo, Thomas; Smith, Harvey Henry (1989). Lebanon: a country study (PDF). Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 73. OCLC 556223794. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- Tsukanova, Vera; Prusskaya, Evgeniya (2019). "Contacts in the MENA region: a brief introduction". Middle East – Topics & Arguments. Center for Near and Middle Eastern Studies. 13 (13): 8–9. doi:10.17192/meta.2019.13.8245.

- "Kurds". Minority Rights Group International. 19 June 2015. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- McLoughlin, Leslie J. (2009). Colloquial Arabic (Levantine): Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Jordan (2nd ed.). Routledge. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-0-203-88074-6. OCLC 313867477.

- Guedri, Christine Marie (2008). A Sociolinguistic Study of Language Contact of Lebanese Arabic and Brazilian Portuguese in São Paulo (PhD thesis). University of Texas at Austin. p. 101. OCLC 844206664. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- Syria, in Eberhard, David M.; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D., eds. (2023). Ethnologue: Languages of the World (26th ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

- Jordan, in Eberhard, David M.; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D., eds. (2023). Ethnologue: Languages of the World (26th ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International.