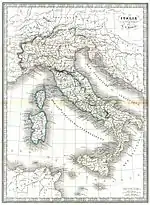

Military history of Italy during World War II

The participation of Italy in the Second World War was characterized by a complex framework of ideology, politics, and diplomacy, while its military actions were often heavily influenced by external factors. Italy joined the war as one of the Axis Powers in 1940 (as the French Third Republic surrendered) with a plan to concentrate Italian forces on a major offensive against the British Empire in Africa and the Middle East, known as the "parallel war", while expecting the collapse of British forces in the European theatre. The Italians bombed Mandatory Palestine, invaded Egypt and occupied British Somaliland with initial success. However, the British counterattacked, eventually necessitating German support to prevent an Italian collapse in North Africa. As the war carried on and German and Japanese actions in 1941 led to the entry of the Soviet Union and United States, respectively, into the war, the Italian plan of forcing Britain to agree to a negotiated peace settlement was foiled.[1]

| History of Italy |

|---|

|

|

|

The Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was aware that Fascist Italy was not ready for a long conflict, as its resources were reduced by successful but costly pre-WWII conflicts: the pacification of Libya (which was undergoing Italian settlement), intervention in Spain (where a friendly fascist regime had been installed), and the invasion of Ethiopia and Albania. However, he opted to remain in the war as the imperial ambitions of the Fascist regime, which aspired to restore the Roman Empire in the Mediterranean (the Mare Nostrum), were partially met by late 1942, albeit with a great deal of German assistance.

With the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia and the Balkans, Italy annexed Ljubljana, Dalmatia and Montenegro, and established the puppet states of Croatia and Greece. Following Vichy France's collapse and the Case Anton, Italy occupied the French territories of Corsica and Tunisia. Italian forces had also achieved victories against insurgents in Yugoslavia and in Montenegro, and Italo-German forces had occupied parts of British-held Egypt on their push to El-Alamein after their victory at Gazala.

However, Italy's conquests were always heavily contested, both by various insurgencies (most prominently the Greek resistance and Yugoslav partisans) and Allied military forces, which waged the Battle of the Mediterranean throughout and beyond Italy's participation. The country's imperial overstretch (opening multiple fronts in Africa, the Balkans, Eastern Europe, and the Mediterranean) ultimately resulted in its defeat in the war, as the Italian empire collapsed after disastrous defeats in the Eastern European and North African campaigns. In July 1943, following the Allied invasion of Sicily, Mussolini was arrested by order of King Victor Emmanuel III, provoking a civil war. Italy's military outside of the Italian peninsula collapsed, its occupied and annexed territories falling under German control. Under Mussolini's successor Pietro Badoglio, Italy capitulated to the Allies on 3 September 1943, although Mussolini would be rescued from captivity a week later by German forces without meeting resistance. On 13 October 1943, the Kingdom of Italy officially joined the Allied Powers and declared war on its former Axis partner Germany.[2]

The northern half of the country was occupied by the Germans with the cooperation of Italian fascists, and became a collaborationist puppet state (with more than 800,000 soldiers, police, and militia recruited for the Axis), while the south was officially controlled by monarchist forces, which fought for the Allied cause as the Italian Co-Belligerent Army (at its height numbering more than 50,000 men), as well as around 350,000[3] Italian resistance movement partisans (many of them ex-Royal Italian Army soldiers) of disparate political ideologies operated all over Italy. On 28 April 1945, Mussolini was assassinated by Italian partisans at Giulino, two days before Hitler's suicide. Unlike Germany and Japan, no war crimes tribunals were held for Italian military and political leaders, though the Italian resistance summarily executed some political members at the end of the war.

Background

Imperial ambitions

Legend:

During the late 1920s, the Italian Prime Minister Benito Mussolini spoke with increasing urgency about imperial expansion, arguing that Italy needed an outlet for its "surplus population" and that it would therefore be in the best interests of other countries to aid in this expansion.[4] The immediate aspiration of the regime was political "hegemony in the Mediterranean–Danubian–Balkan region", more grandiosely Mussolini imagined the conquest "of an empire stretching from the Strait of Gibraltar to the Strait of Hormuz".[5] Balkan and Mediterranean hegemony was predicated by ancient Roman dominance in the same regions. There were designs for a protectorate over Albania and for the annexation of Dalmatia, as well as economic and military control of Yugoslavia and Greece. The regime also sought to establish protective patron–client relationships with Austria, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria, which all lay on the outside edges of its European sphere of influence.[6] Although it was not among his publicly proclaimed aims, Mussolini wished to challenge the supremacy of Britain and France in the Mediterranean Sea, which was considered strategically vital, since the Mediterranean was Italy's only conduit to the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.[4]

In 1935, Italy initiated the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, "a nineteenth-century colonial campaign waged out of due time". The campaign gave rise to optimistic talk on raising a native Ethiopian army "to help conquer" Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. The war also marked a shift towards a more aggressive Italian foreign policy and also "exposed [the] vulnerabilities" of the British and French. This in turn created the opportunity Mussolini needed to begin to realize his imperial goals.[7][8] In 1936, the Spanish Civil War broke out. From the beginning, Italy played an important role in the conflict. Their military contribution was so vast, that it played a decisive role in the victory of the rebel forces led by Francisco Franco.[9] Mussolini had engaged in "a full-scale external war" due to the insinuation of future Spanish subservience to the Italian Empire, and as a way of placing the country on a war footing and creating "a warrior culture".[10] The aftermath of the war in Ethiopia saw a reconciliation of German-Italian relations following years of a previously strained relationship, resulting in the signing of a treaty of mutual interest in October 1936. Mussolini referred to this treaty as the creation of a Berlin-Rome Axis, which Europe would revolve around. The treaty was the result of increasing dependence on German coal following League of Nations sanctions, similar policies between the two countries over the conflict in Spain, and German sympathy towards Italy following European backlash to the Ethiopian War. The aftermath of the treaty saw the increasing ties between Italy and Germany, and Mussolini falling under Adolf Hitler's influence from which "he never escaped".[11][12][13]

In October 1938, in the aftermath of the Munich Agreement, Italy demanded concessions from France. These included a free port at Djibouti, control of the Addis Ababa-Djibouti railroad, Italian participation in the management of Suez Canal Company, some form of French-Italian condominium over French Tunisia, and the preservation of Italian culture on Corsica with no French assimilation of the people. The French refused the demands, believing the true Italian intention was the territorial acquisition of Nice, Corsica, Tunisia, and Djibouti.[14] On 30 November 1938, Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano addressed the Chamber of Deputies on the "natural aspirations of the Italian people" and was met with shouts of "Nice! Corsica! Savoy! Tunisia! Djibouti! Malta!"[15] Later that day, Mussolini addressed the Fascist Grand Council "on the subject of what he called the immediate goals of 'Fascist dynamism'." These were Albania; Tunisia; Corsica; the Ticino, a canton of Switzerland; and all "French territory east of the River Var", including Nice, but not Savoy.[16]

Beginning in 1939 Mussolini often voiced his contention that Italy required uncontested access to the world's oceans and shipping lanes to ensure its national sovereignty.[17] On 4 February 1939, Mussolini addressed the Grand Council in a closed session. He delivered a long speech on international affairs and the goals of his foreign policy, "which bears comparison with Hitler's notorious disposition, minuted by colonel Hossbach". He began by claiming that the freedom of a country is proportional to the strength of its navy. This was followed by "the familiar lament that Italy was a prisoner in the Mediterranean".[lower-alpha 1] He called Corsica, Tunisia, Malta, and Cyprus "the bars of this prison", and described Gibraltar and Suez as the prison guards.[19][20] To break British control, her bases on Cyprus, Gibraltar, Malta, and in Egypt (controlling the Suez Canal) would have to be neutralized. On 31 March, Mussolini stated that "Italy will not truly be an independent nation so long as she has Corsica, Bizerta, Malta as the bars of her Mediterranean prison and Gibraltar and Suez as the walls." Fascist foreign policy took for granted that the democracies—Britain and France—would someday need to be faced down.[21][22][17] Through armed conquest Italian North Africa and Italian East Africa—separated by the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan—would be linked,[23] and the Mediterranean prison destroyed. Then, Italy would be able to march "either to the Indian Ocean through the Sudan and Abyssinia, or to the Atlantic by way of French North Africa".[16]

As early as September 1938, the Italian military had drawn up plans to invade Albania. On 7 April, Italian forces landed in the country and within three days had occupied the majority of the country. Albania represented a territory Italy could acquire for "'living space' to ease its overpopulation" as well as the foothold needed to launch other expansionist conflicts in the Balkans.[24] On 22 May 1939, Italy and Germany signed the Pact of Steel joining both countries in a military alliance. The pact was the culmination of German-Italian relations from 1936 and was not defensive in nature.[25] Rather, the pact was designed for a "joint war against France and Britain", although the Italian hierarchy held the understanding that such a war would not take place for several years.[26] However, despite the Italian impression, the pact made no reference to such a period of peace and the Germans proceeded with their plans to invade Poland.[27]

Industrial strength

Mussolini's Under-Secretary for War Production, Carlo Favagrossa, had estimated that Italy could not possibly be prepared for major military operations until at least October 1942. This had been made clear during the Italo-German negotiations for the Pact of Steel, whereby it was stipulated that neither signatory was to make war without the other earlier than 1943.[28] Although considered a great power, the Italian industrial sector was relatively weak compared to other European major powers. Italian industry did not equal more than 15% of that of France or of Britain in militarily critical areas such as automobile production: the number of automobiles in Italy before the war was around 374,000, in comparison to around 2,500,000 in Britain and France. The lack of a stronger automotive industry made it difficult for Italy to mechanize its military. Italy still had a predominantly agricultural-based economy, with demographics more akin to a developing country (high illiteracy, poverty, rapid population growth and a high proportion of adolescents) and a proportion of GNP derived from industry less than that of Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Sweden, in addition to the other great powers.[29] In terms of strategic materials, in 1940, Italy produced 4.4 megatonnes (Mt) of coal, 0.01 Mt of crude oil, 1.2 Mt of iron ore and 2.1 Mt of steel. By comparison, Great Britain produced 224.3 Mt of coal, 11.9 Mt of crude oil, 17.7 Mt of iron ore, and 13.0 Mt of steel and Germany produced 364.8 Mt of coal, 8.0 Mt of crude oil, 29.5 Mt of iron ore and 21.5 Mt of steel.[30] Most raw material needs could be fulfilled only through importation, and no effort was made to stockpile key materials before the entry into war. Approximately one quarter of the ships of Italy's merchant fleet were in allied ports at the outbreak of hostilities, and, given no forewarning, were immediately impounded.[31][32]

Economy

Between 1936 and 1939, Italy had supplied the Spanish Nationalist forces, fighting under Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War, with large number of weapons and supplies practically free.[33][34] In addition to weapons, the Corpo Truppe Volontarie ("Corps of Volunteer Troops") had also been dispatched to fight for Franco. The financial cost of the war was between 6 and 8.5 billion lire, approximately 14 to 20 per cent of the country's annual expenditure.[34] Adding to these problems was Italy's extreme debt position. When Benito Mussolini took office, in 1921, the government debt was 93 billion lire, un-repayable in the short to medium term. Only two years later this debt had increased to 405 billion lire.[35]

In September 1939, Britain imposed a selective blockade of Italy. Coal from Germany, which was shipped out of Rotterdam, was declared contraband. The Germans promised to keep up shipments by train, over the Alps, and Britain offered to supply all of Italy's needs in exchange for Italian armaments. The Italians could not agree to the latter terms without shattering their alliance with Germany.[36] On 2 February 1940, however, Mussolini approved a draft contract with the Royal Air Force to provide 400 Caproni aircraft, yet scrapped the deal on 8 February. British intelligence officer Francis Rodd believed that Mussolini was convinced to reverse policy by German pressure in the week of 2–8 February, a view shared by the British ambassador in Rome, Percy Loraine.[37] On 1 March, the British announced that they would block all coal exports from Rotterdam to Italy.[36][37] Italian coal was one of the most discussed issues in diplomatic circles in the spring of 1940. In April, Britain began strengthening the Mediterranean Fleet to enforce the blockade. Despite French uncertainty, Britain rejected concessions to Italy so as not to "create an impression of weakness".[38] Germany supplied Italy with about one million tons of coal a month beginning in the spring of 1940, an amount that exceeded even Mussolini's demand of August 1939 that Italy receive six million tons of coal for its first twelve months of war.[39]

Military

The Italian Royal Army (Regio Esercito) was comparatively depleted and weak at the beginning of the war. Italian tanks were of poor quality and radios few in number. The bulk of Italian artillery dated to World War I. The primary fighter of the Italian Air Force (Regia Aeronautica) was the Fiat CR.42 Falco, which, though an advanced biplane with excellent performance, was technically outclassed by monoplane fighters of other nations.[40] Of the Regia Aeronautica's approximately 1,760 aircraft, only 900 could be considered in any way combat-worthy. The Italian Royal Navy (Regia Marina) had several modern battleships but no aircraft carriers.[41]

Italian authorities were acutely aware of the need to modernize and were taking steps to meet the requirements of their own relatively advanced tactical principles.[nb 1][nb 2][44][45] Almost 40% of the 1939 budget was allocated for military spending.[46] Recognizing the Navy's need for close air support, the decision was made to build carriers.[nb 3] Three series of modern fighters[nb 4], capable of meeting the best allied planes on equal terms,[48][nb 5] were in development, with a few hundred of each eventually being produced. The Carro Armato P40 tank,[49] roughly equivalent to the M4 Sherman and Panzer IV medium tanks, was designed in 1940 (though no prototype was produced until 1942 and manufacture could not commence before the Armistice, [nb 6] owing in part to the lack of sufficiently powerful engines, which were themselves undergoing a development push; total Italian tank production for the war – about 3,500 – was less than the number of tanks used by Germany in its invasion of France). The Italians were pioneers in the use of self-propelled guns,[52][53] both in close support and anti-tank roles. Their 75/46 fixed AA/AT gun, 75/32 gun, 90/53 AA/AT gun (an equally deadly but less famous peer of the German 88/55), 47/32 AT gun, and the 20 mm AA autocannon were effective, modern weapons.[45][54] Also of note were the AB 41 and the Camionetta AS 42 armoured cars, which were regarded as excellent vehicles of their type.[55][56] None of these developments, however, precluded the fact that the bulk of equipment was obsolete and poor.[57] The relatively weak economy, lack of suitable raw materials and consequent inability to produce sufficient quantities of armaments and supplies were thus the key material reasons for Italian military failure.[58]

On paper, Italy had one of the world's largest armies,[59] but the reality was dramatically different. According to the estimates of Bierman and Smith, the Italian regular army could field only about 200,000 troops at the war's beginning.[41] Irrespective of the attempts to modernize, the majority of Italian army personnel were lightly armed infantry lacking sufficient motor transport.[nb 7] Not enough money was budgeted to train the men in the services, such that the bulk of personnel received much of their training at the front, too late to be of use.[60] Air units had not been trained to operate with the naval fleet and the majority of ships had been built for fleet actions, rather than the convoy protection duties in which they were primarily employed during the war.[61] In any event, a critical lack of fuel kept naval activities to a minimum.[62]

Senior leadership was also a problem. Mussolini personally assumed control of all three individual military service ministries with the intention of influencing detailed planning.[63] Comando Supremo (the Italian High Command) consisted of only a small complement of staff that could do little more than inform the individual service commands of Mussolini's intentions, after which it was up to the individual service commands to develop proper plans and execution.[64] The result was that there was no central direction for operations; the three military services tended to work independently, focusing only on their fields, with little inter-service cooperation.[64][65] Pay discrepancies existed for personnel who were of equal rank, but from different units.

Outbreak of the Second World War

Nazi Germany's invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939, marked the beginning of World War II. Despite being an Axis power, Italy remained non-belligerent until June 1940.

Decision to intervene

Following the German conquest of Poland, Mussolini hesitated to enter the war. The British commander for land forces in the Middle East and the eastern Mediterranean, General Sir Archibald Wavell, correctly predicted that Mussolini's pride would ultimately cause him to enter the war. Wavell would compare Mussolini's situation to that of someone at the top of a diving board: "I think he must do something. If he cannot make a graceful dive, he will at least have to jump in somehow; he can hardly put on his dressing-gown and walk down the stairs again."[66]

Initially, the entry into the war appeared to be political opportunism (though there was some provocation),[nb 8] which led to a lack of consistency in planning, with principal objectives and enemies being changed with little regard for the consequences.[71] Mussolini was well aware of the military and material deficiencies but thought the war would be over soon and did not expect to do much fighting.

Italy enters the war: June 1940

On 10 June 1940, as the French government fled to Bordeaux during the German invasion, declaring Paris an open city, Mussolini felt the conflict would soon end and declared war on Britain and France. As he said to the Army's Chief-of-Staff, Marshal Badoglio:

I only need a few thousand dead so that I can sit at the peace conference as a man who has fought.[72]

Mussolini had the immediate war aim of expanding the Italian colonies in North Africa by taking land from the British and French colonies.

About Mussolini's declaration of war in France, President Franklin D. Roosevelt of the United States said:

On this tenth day of June 1940, the hand that held the dagger has struck it into the back of its neighbor.[73]

The Italian entry into the war opened up new fronts in North Africa and the Mediterranean. After Italy entered the war, pressure from Nazi Germany led to the internment in the Campagna concentration camp of some of Italy's Jewish refugees.

Invasion of France

In June 1940, after initial success, the Italian offensive into southern France stalled at the fortified Alpine Line. On 24 June 1940, France surrendered to Germany. Italy occupied a swath of French territory along the Franco-Italian border. During this operation, Italian casualties amounted to 1,247 men dead or missing and 2,631 wounded. A further 2,151 Italians were hospitalised due to frostbite.

Late in the Battle of Britain, Italy contributed an expeditionary force, the Corpo Aereo Italiano, which took part in the Blitz from October 1940 until April 1941, at which time the last elements of the force were withdrawn.

In November 1942, the Italian Royal Army occupied south-eastern Vichy France and Corsica as part of Case Anton. From December 1942, Italian military government of French departments east of the Rhône River was established, and continued until September 1943, when Italy quit the war. This had the effect of providing a de facto temporary haven for French Jews fleeing the Holocaust. In January 1943 the Italians refused to cooperate with the Nazis in rounding up Jews living in the occupied zone of France under their control and in March prevented the Nazis from deporting Jews in their zone. German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop complained to Mussolini that "Italian military circles... lack a proper understanding of the Jewish question."[74]

The Italian Navy established a submarine base at Bordeaux, code named BETASOM, and thirty two Italian submarines participated in the Battle of the Atlantic. Plans to attack the harbour of New York City with CA class midget submarines in 1943 were disrupted when the submarine converted to carry out the attack, the Leonardo da Vinci, was sunk in May 1943.[75] The armistice put a stop to further planning.

North Africa

Invasion of Egypt

Within a week of Italy's declaration of war on 10 June 1940, the British 11th Hussars had seized Fort Capuzzo in Libya. In an ambush east of Bardia, the British captured the Italian 10th Army Engineer-in-Chief, General Lastucci. On 28 June Marshal Italo Balbo, the Governor-General of Libya, was killed by friendly fire while landing in Tobruk. Mussolini ordered Balbo's replacement, General Rodolfo Graziani, to launch an attack into Egypt immediately. Graziani complained to Mussolini that his forces were not properly equipped for such an operation, and that an attack into Egypt could not possibly succeed; nevertheless, Mussolini ordered him to proceed.[76] On 13 September, elements of the 10th Army retook Fort Capuzzo and crossed the border into Egypt. Lightly opposed, they advanced about 100 km (60 mi) to Sidi Barrani, where they stopped and began entrenching themselves in a series of fortified camps.

.jpg.webp)

At this time, the British had only 36,000 troops available (out of about 100,000 under Middle Eastern command) to defend Egypt, against 236,000 Italian troops.[77] The Italians, however, were not concentrated in one location. They were divided between the 5th army in the west and the 10th army in the east and thus spread out from the Tunisian border in western Libya to Sidi Barrani in Egypt. At Sidi Barrani, Graziani, unaware of the British lack of numerical strength,[nb 9] planned to build fortifications and stock them with provisions, ammunition, and fuel, establish a water pipeline, and extend the via Balbia to that location, which was where the road to Alexandria began.[79] This task was being obstructed by British Royal Navy attacks on Italian supply ships in the Mediterranean. At this stage Italian losses remained minimal, but the efficiency of the British Royal Navy would improve as the war went on. Mussolini was fiercely disappointed with Graziani's sluggishness. However, according to Bauer[79] he had only himself to blame, as he had withheld the trucks, armaments, and supplies that Graziani had deemed necessary for success. Wavell was hoping to see the Italians overextend themselves before his intended counter at Marsa Matruh.[79]

One officer of Graziani wrote: "We're trying to fight this... as though it were a colonial war... this is a European war... fought with European weapons against a European enemy. We take too little account of this in building our stone forts.... We are not fighting the Ethiopians now."[80](This was a reference to the Second Italo-Abyssinian War where Italian forces had fought against a poorly equipped opponent.) Balbo had said "Our light tanks, already old and armed only with machine guns, are completely out-classed. The machine guns of the British armoured cars pepper them with bullets which easily pierce their armour."[79]

Italian forces around Sidi Barrani had severe weaknesses in their deployment. Their five main fortifications were placed too far apart to allow mutual support against an attacking force, and the areas between were weakly patrolled. The absence of motorised transport did not allow for rapid reorganisation, if needed. The rocky terrain had prevented an anti-tank ditch from being dug and there were too few mines and 47 mm anti-tank guns to repel an armoured advance.[78] By the summer of 1941, the Italians in North Africa had regrouped, retrained and rearmed into a much more effective fighting force, one that proved to be much harder for the British to overcome in encounters from 1941 to 1943.[81]

Afrika Korps intervention and final defeat

On 8 December 1940, the British launched Operation Compass. Planned as an extended raid, it resulted in a force of British, Indian, and Australian troops cutting off the Italian 10th Army. Pressing the British advantage home, General Richard O'Connor succeeded in reaching El Agheila, deep in Libya (an advance of 800 kilometres or 500 miles) and taking some 130,000 prisoners.[82] The Allies nearly destroyed the 10th Army, and seemed on the point of sweeping the Italians out of Libya altogether. Winston Churchill, however, directed the advance be stopped, initially because of supply problems and because of a new Italian offensive that had gained ground in Albania, and ordered troops dispatched to defend Greece. Weeks later the first troops of the German Afrika Korps started to arrive in North Africa (February 1941), along with six Italian divisions including the motorized Trento and armored Ariete.[83][84]

German General Erwin Rommel now became the principal Axis field commander in North Africa, although the bulk of his forces consisted of Italian troops. Though subordinate to the Italians, under Rommel's direction the Axis troops pushed the British and Commonwealth troops back into Egypt but were unable to complete the task because of the exhaustion and their extended supply lines which were under threat from the Allied enclave at Tobruk, which they failed to capture. After reorganising and re-grouping the Allies launched Operation Crusader in November 1941 which resulted in the Axis front line being pushed back once more to El Agheila by the end of the year.

In January 1942 the Axis struck back again, advancing to Gazala where the front lines stabilised while both sides raced to build up their strength. At the end of May, Rommel launched the Battle of Gazala where the British armoured divisions were soundly defeated. The Axis seemed on the verge of sweeping the British out of Egypt, but at the First Battle of El Alamein (July 1942) General Claude Auchinleck halted Rommel's advance only 140 km (90 mi) from Alexandria. Rommel made a final attempt to break through during the Battle of Alam el Halfa but Eighth Army, by this time commanded by Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery, held firm. After a period of reinforcement and training the Allies assumed the offensive at the Second Battle of Alamein (October/November 1942) where they scored a decisive victory and the remains of Rommel's German-Italian Panzer Army were forced to engage in a fighting retreat for 2,600 km (1,600 mi) to the Libyan border with Tunisia.

After the Operation Torch landings in the Vichy French territories of Morocco and Algeria (November 1942) British, American and French forces advanced east to engage the German-Italian forces in the Tunisia Campaign. By February, the Axis forces in Tunisia were joined by Rommel's forces, after their long withdrawal from El Alamein, which were re-designated the Italian First Army (under Giovanni Messe) when Rommel left to command the Axis forces to the north at the Battle of the Kasserine Pass. Despite the Axis success at Kasserine, the Allies were able to reorganise (with all forces under the unified direction of 18th Army Group commanded by General Sir Harold Alexander) and regain the initiative in April. The Allies completed the defeat of the Axis armies in North Africa in May 1943.

East Africa

In addition to the well-known campaigns in the western desert during 1940, the Italians initiated operations in June 1940 from their East African colonies of Ethiopia, Italian Somaliland, and Eritrea.

As in Egypt, Italian forces (roughly 70,000 Italian soldiers and 180,000 native troops) outnumbered their British opponents. Italian East Africa, however, was isolated and far from the Italian mainland, leaving the forces there cut off from supply and thus severely limited in the operations they could undertake.

Initial Italian attacks in East Africa took two different directions, one into Sudan and the other into Kenya. Then, in August 1940, the Italians advanced into British Somaliland. After suffering and inflicting few casualties, the British and Commonwealth garrison evacuated Somaliland, retreating by sea to Aden.

The Italian invasion of British Somaliland was one of the few successful Italian campaigns of World War II accomplished without German support. In Sudan and Kenya, Italy captured small territories around several border villages, after which the Italian Royal Army in East Africa adopted a defensive posture in preparation for expected British counterattacks.

The Regia Marina maintained a small squadron in the Italian East Africa area. The "Red Sea Flotilla", consisting of seven destroyers and eight submarines, was based at the port of Massawa in Eritrea. Despite a severe shortage of fuel, the flotilla posed a threat to British convoys traversing the Red Sea. However, Italian attempts to attack British convoys resulted in the loss of four submarines and one destroyer.[85]

On 19 January 1941, the expected British counter-attack arrived in the shape of the Indian 4th and Indian 5th Infantry Divisions, which made a thrust from Sudan. A supporting attack was made from Kenya by the South African 1st Division, the 11th African Division, and the 12th African Division. Finally, the British launched an amphibious assault from Aden to re-take British Somaliland.

Fought from February to March, the outcome of the Battle of Keren determined the fate of Italian East Africa. In early April, after Keren fell, Asmara and Massawa followed. The Ethiopian capital of Addis Ababa also fell in April 1941. The Viceroy of Ethiopia, Amedeo, Duke of Aosta, surrendered at the stronghold of Amba Alagi in May. He received full military honours. The Italians in East Africa made a final stand around the town of Gondar in November 1941.

When the port of Massawa fell to the British, the remaining destroyers were ordered on final missions in the Red Sea, some of them achieving small successes before being scuttled or sunk. At the same time, the last four submarines made an epic voyage around the Cape of Good Hope to Bordeaux in France. Some Italians, after their defeat, waged a guerilla war mainly in Eritrea and Ethiopia, that lasted until fall 1943. Notable among them was Amedeo Guillet.

Balkans

Invasion of Albania

In early 1939, while the world was focused on Adolf Hitler's aggression against Czechoslovakia, Mussolini looked to the Kingdom of Albania, across the Adriatic Sea from Italy. Italian forces invaded Albania on 7 April 1939 and swiftly took control of the small country. Even before the invasion, Albania had been politically dominated by Italy; after the invasion it was formally made a protectorate of Italy and the Italian king took the Albanian crown. Along with the intervention in the Spanish Civil War and the invasion of Abyssinia, the invasion of Albania was part of the Italian contribution to the disintegration of the collective security the League of Nations instituted after World War I. As such, it was part of the prelude to World War II.

Invasion of Greece

On 28 October 1940, Italy started the Greco-Italian War by launching an invasion of the Kingdom of Greece from Albania. In part, the Italians attacked Greece because of the growing influence of Germany in the Balkans. Both Yugoslavia and Greece had governments friendly to Germany. Mussolini launched the invasion of Greece in haste after the Kingdom of Romania, a state which he perceived as lying within the Italian sphere of influence, allied itself with Germany. The order to invade Greece was given by Mussolini to Badoglio and Army Chief of Staff Mario Roatta on 15 October, with the expectation that the attack would commence within 12 days. Badoglio and Roatta were appalled given that, acting on his orders, they had demobilised 600,000 men three weeks prior.[86] Given the expected requirement of at least 20 divisions to facilitate success, the fact that only eight divisions were currently in Albania, and the inadequacies of Albanian ports and connecting infrastructure, adequate preparation would require at least three months.[86] Nonetheless, D-day was set at dawn on 28 October.

The initial Italian offensive was quickly contained, and the invasion soon ended in an embarrassing stalemate. Taking advantage of Bulgaria's decision to remain neutral, the Greek Commander-in-Chief, Lt Gen Alexandros Papagos, was able to establish numerical superiority by mid-November,[nb 10] prior to launching a counter-offensive that drove the Italians back into Albania. In addition, the Greeks were naturally adept at operating in mountainous terrain, while only six of the Italian Army's divisions, the Alpini, were trained and equipped for mountain warfare. Only when the Italians were able to establish numerical parity was the Greek offensive stopped. By then they had been able to penetrate deep into Albania.

An Italian "Spring Offensive" in March 1941, which tried to salvage the situation prior to German intervention, amounted to little in terms of territorial gains. At this point, combat casualties amounted to over 102,000 for the Italians (with 13,700 dead and 3,900 missing) and fifty thousand sick; the Greek suffered over 90,000 combat casualties (including 14,000 killed and 5,000 missing) and an unknown number of sick.[89] While an embarrassment for the Italians, losses on this scale were devastating for the less numerous Greeks; additionally, the Greek Army had bled a significant amount of materiel. They were short on every area of equipment despite heavy infusion of British aid in February and March, with the army as a whole having only 1 month of artillery ammunition left by the start of April and insufficient arms and equipment to mobilize its reserves.[90] Hitler later stated in hindsight that Greece would have been defeated with or without German intervention, and that even at the time he was of the opinion that the Italians alone would have conquered Greece in the forthcoming season.[91]

After British troops arrived in Greece in March 1941, British bombers operating from Greek bases could reach Romanian oil fields, vital to the German war effort. Hitler decided that a British presence in Greece presented a threat to Germany's rear and committed German troops to invade Greece via Yugoslavia (where a coup had deposed the German-friendly government). The Germans invaded on 6 April 1941, smashing through the skeleton garrisons opposing them with little resistance, while the Italians continued a slow advance in Albania and Epirus as the Greeks withdrew, with the country falling to the Axis by the end of the month. The Italian Army was still pinned down in Albania by the Greeks when the Germans began their invasion. Crucially, the bulk of the Greek Army (fifteen divisions out of twenty-one) was left facing the Italians in Albania and Epirus when the Germans intervened. Hitler commented that the Italians "had so weakened [Greece] that its collapse had already become inevitable", and credited them with having "engaged the greater part of the Greek Army."[91]

Invasion of Yugoslavia

On 6 April 1941, the Wehrmacht invasions of both Yugoslavia (Operation 25) and Greece (Operation Marita) began. Together with the rapid advance of German forces, the Italians attacked Yugoslavia in Dalmatia and finally pushed the Greeks out of Albania. On 17 April, Yugoslavia surrendered to the Germans and the Italians. On 30 April, Greece too surrendered to the Germans and Italians, and was divided into German, Italian and Bulgarian sectors. The invasions ended with a complete Axis victory in May when Crete fell. On 3 May, during the triumphal parade in Athens to celebrate the Axis victory, Mussolini started to boast of an Italian Mare Nostrum in the Mediterranean.

Some 28 Italian divisions participated in the Balkan invasions. The coast of Yugoslavia was occupied by the Italian Army, while the rest of the country was divided between the Axis forces (a German and Italian creation, the Independent State of Croatia was born, under the nominal sovereignty of Prince Aimone, Duke of Aosta, but actually governed by the Croatian leader Ante Pavelić). The Italians assumed control of most of Greece with their 11th Army, while the Bulgarians occupied the northern provinces and the Germans the strategically most important areas. Italian troops would occupy parts of Greece and Yugoslavia until the Italian armistice with the Allies in September 1943.

In spring 1941, Italy created a Montenegrin client state and annexed most of the Dalmatian coast as the Governorship of Dalmatia (Governatorato di Dalmazia). A complicated four-way conflict between the puppet Montenegro regime, Montenegrin nationalists, Royalist remnants of the Yugoslav government, and Communist Partisans continued from 1941 to 1945.

In 1942, the Italian military commander in Croatia refused to hand over Jews in his zone to the Nazis.[74]

Mediterranean

In 1940, the Italian Royal Navy (Regia Marina) could not match the overall strength of the British Royal Navy in the Mediterranean Sea. After some initial setbacks, the Italian Navy declined to engage in a confrontation of capital ships. Since the British Navy had as a principal task the supply and protection of convoys supplying Britain's outposts in the Mediterranean, the mere continued existence of the Italian fleet (the so-called "fleet in being" concept) caused problems for Britain, which had to use warships sorely needed elsewhere to protect Mediterranean convoys. On 11 November, Britain launched the first carrier strike of the war, using a squadron of Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers to attack Taranto. The raid left three Italian battleships crippled or destroyed for the loss of two British aircraft shot down.

The Italian navy found other ways to attack the British. The most successful involved the use of frogmen and manned torpedoes to attack ships in harbour. The 10th Light Flotilla, also known as Decima Flottiglia MAS or Xª MAS, which carried out these attacks, sank or damaged 28 ships from September 1940 to the end of 1942. These included the battleships HMS Queen Elizabeth and Valiant (damaged in the harbour of Alexandria on 18 December 1941), and 111,527 long tons (113,317 t) of merchant shipping. The Xª MAS used a particular kind of torpedo, the SLC (Siluro a Lenta Corsa), whose crew was composed of two frogmen, and motorboats packed with explosives, called MTM (Motoscafo da Turismo Modificato).

Following the attacks on the two British battleships, the possibility of Italian dominance over the Mediterranean appeared more achievable. However, Mussolini's brief period of relative success did not last. The oil and supplies brought to Malta, despite heavy losses, by Operation Pedestal in August and the Allied landings in North Africa, Operation Torch, in November 1942, turned the fortunes of war against Italy. The Axis forces were ejected from Libya and Tunisia six months after the Battle of El Alamein, while their supply lines were harassed day after day by the growing and overwhelming aerial and naval supremacy of the Allies. By the summer of 1943, the Allies were poised to invade the Italian homeland.

Eastern Front

In July 1941, some 62,000 Italian troops of the Italian Expeditionary Corps in Russia (Corpo di Spedizione Italiano in Russia, CSIR) left for the Eastern Front to aid in the German invasion of the Soviet Union (Operation Barbarossa). In July 1942, the Italian Royal Army (Regio Esercito) expanded the CSIR to a full army of about 200,000 men named the Italian Army in Russia (Armata Italiana in Russia, ARMIR). ARMIR was also known as the 8th Army. From August 1942 to February 1943, the 8th Army took part in the Battle of Stalingrad and suffered many losses (some 20,000 dead and 64,000 captured) when the Soviets isolated the German forces in Stalingrad by attacking the over-stretched Hungarian, Romanian and Italian forces protecting the Germans' flanks. By the summer of 1943, Rome had withdrawn the remnants of the 8th Army to Italy. Many of the Italian POWs captured in the Soviet Union died in captivity due to harsh conditions in Soviet prison camps.

Allied Italian Campaign and Italian Civil War

Allied invasion of Sicily, fall of Mussolini and armistice

196.jpg.webp)

On 10 July 1943, a combined force of American and British Commonwealth troops invaded Sicily. German generals again took the lead in the defence and, although they lost the island after weeks of bitter fighting, they succeeded in ferrying large numbers of German and Italian forces safely off Sicily to the Italian mainland. On 19 July, an Allied air raid on Rome destroyed both military and collateral civilian structures. With these two events, popular support for the war diminished in Italy.[92]

On 25 July, the Grand Council of Fascism voted to limit the power of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini and handed control of the Italian armed forces over to King Victor Emmanuel III. The next day, Mussolini met with the King, was dismissed as prime minister, and then imprisoned. A new Italian government, led by General Pietro Badoglio and Victor Emmanuel III, took over in Italy. Although they publicly declared that they would keep fighting alongside the Germans, the new Italian government began secret negotiations with the Allies to come over to the Allied side.[93] On 3 September, a secret armistice was signed with the Allies at Fairfield Camp in Sicily. The armistice was publicly announced on 8 September. By then, the Allies were on the Italian mainland.

On 3 September, British troops crossed the short distance from Sicily to the 'toe' of Italy in Operation Baytown. Two more Allied landings took place on 9 September at Salerno (Operation Avalanche) and at Taranto (Operation Slapstick). The Italian surrender meant that the Allied landings at Taranto took place unopposed, with the troops simply disembarking from warships at the docks rather than assaulting the coastline.

_in_Stadt.jpg.webp)

Because of the time it took for the new Italian government to negotiate the armistice, the Germans had time to reinforce their presence in Italy and prepare for their defection. In the first weeks of August, they increased the number of divisions in Italy from two to seven and took control of vital infrastructure.[94] Once the signing of the armistice was announced on 8 September, German troops quickly disarmed the Italian forces and took over critical defensive positions in Operation Achse. This included Italian-occupied southeastern France and the Italian-controlled areas in the Balkans. Only in Sardinia, Corsica, and in part of Apulia and Calabria were Italian troops able to hold their positions until the arrival of Allied forces. In the area of Rome, only one infantry division—the Granatieri di Sardegna—and some small armoured units fought with commitment, but by 11 September were overwhelmed by superior German forces.

King Victor Emmanuel III and his family, with Marshal Badoglio, General Mario Roatta, and others, abandoned Rome on 9 September. General Caroni, who was tasked with defending Rome, was given duplicitous orders to have his troops abandon Rome (something he did not want to do), and essentially to provide rear guard protection to the King and his entourage so they could flee to the Abruzzi hills, and later out to sea. They later landed at Brindisi. Most importantly, Badoglio never gave the "OP 44" order for the Italian people to rise up against the Germans until he knew it was too late to do any good; that is, he belatedly issued the order on 11 September. However, from the day of the announcement of the Armistice, when Italian citizens, military personnel and military units decided to rise up and resist on their own; they were sometimes quite effective against the Germans.[95]

As part of the terms of the armistice, the Italian fleet was to sail to Malta for internment; as it did so, it came under air attack by German bombers, and on 9 September two German Fritz X guided bombs sank the Italian battleship Roma off the coast of Sardinia.[96] A Supermarina (Italian Naval Command) broadcast led the Italians to initially believe this attack was carried out by the British.[97]

On the Greek island of Cephallonia, General Antonio Gandin, commander of the 12,000-strong Italian Acqui Division, decided to resist the German attempt to forcibly disarm his force. The battle raged from 13 to 22 September, when the Italians capitulated having suffered some 1,300 casualties. Following the surrender, the Germans proceeded to massacre thousands of the Italian prisoners.

Italian troops captured by the Germans were given a choice to keep fighting with the Germans. About 94,000 Italians accepted and the remaining 710,000 were designated Italian military internees and were transported as forced labour to Germany. Some Italian troops that evaded German capture in the Balkans joined the Yugoslav (about 40,000 soldiers) and Greek Resistance (about 20,000).[98] The same happened in Albania.[99]

After the German invasion, deportations of Italian Jews to Nazi death camps began. However, by the time the German advance reached the Campagna concentration camp, all the inmates had already fled to the mountains with the help of the local inhabitants. Rev. Aldo Brunacci of Assisi, under the direction of his bishop, Giuseppe Nicolini, saved all the Jews who sought refuge in Assisi. In October 1943 Nazis raided the Jewish ghetto in Rome. In November 1943 Jews of Genoa and Florence were deported to Auschwitz. It is estimated that 7,500 Italian Jews became victims of the Holocaust.[74]

Civil war, Allied advance and surrender to Allied forces

After Mussolini had been stripped of power, he was imprisoned at Gran Sasso in the Apennine mountains. On 12 September he was rescued by the Germans in Operation Eiche ("Oak"). The Germans re-located him to northern Italy where he set up a new Fascist state, the Italian Social Republic (Repubblica Sociale Italiana or RSI). Many Italian personalities joined the RSI, like General Rodolfo Graziani.

The Allied armies continued to advance through Italy despite increasing opposition from the Germans. The Allies soon controlled most of southern Italy, and Naples rose against and ejected the occupying German forces. The loyalist Italian government (sometimes referred to as the "Kingdom of the South") declared war on Germany on 13 October, aligning Italy within the Western Allies as a co-belligerent. With Allied assistance some Italian troops in the south were organized into what were known as "co-belligerent" or "royalist" forces. In time, there was a co-belligerent army (Italian Co-Belligerent Army), navy (Italian Co-Belligerent Navy), and air force (Italian Co-Belligerent Air Force). These Italian forces fought alongside the Allies for the rest of the war. Other Italian troops, loyal to Mussolini and his RSI, continued to fight alongside the Germans (among them the Esercito Nazionale Repubblicano, the National Republican Army). From this point on, a large Italian resistance movement located in northern Italy fought a guerilla war against the German and RSI forces.

Winston Churchill had long regarded southern Europe as the military weak spot of the continent (in World War I he had advocated the Dardanelles campaign, and during World War II he favoured the Balkans as an area of operations, for example in Greece in 1940).[100][101][102] Calling Italy the "soft underbelly" of the Axis, Churchill had therefore advocated this invasion instead of a cross-channel invasion of occupied France. But Italy itself proved anything but a soft target: the mountainous terrain gave Axis forces excellent defensive positions, and it also partly negated the Allied advantage in motorized and mechanized units. The final Allied victory over the Axis in Italy did not come until the spring offensive of 1945, after Allied troops had breached the Gothic Line, leading to the surrender of German and RSI forces in Italy on 2 May shortly before Germany finally surrendered ending World War II in Europe on 8 May. Mussolini was captured and killed on 28 April 1945 by the Italian resistance while attempting to flee.

Change of side by the Kingdom of Italy

On 13 October 1943, the Kingdom of Italy, which was now based outside of Mussolini's control, not only joined the Allies, but also declared war on Nazi Germany.[103] Tensions between the Axis and the Italian military were rising following the failure to defend Sicily, with New York Times correspondent Milton Bracker noting that "Italian hatred of the Germans unquestionably grew as the fighting spirit waned, and episodes between German and Italian soldiers and civilians before and after the armistice have shown pretty clearly a complete and incontrovertible end of all sympathy between the former Axis partners."[103]

Italy and Japan after the surrender

Japan reacted with shock and outrage to the news of the surrender of Italy to the Allied forces in September 1943. Italian citizens residing in Japan and in Manchukuo were swiftly rounded up and summarily asked whether they were loyal to the King of Savoy, who dishonoured their country by surrendering to the enemy, or with the Duce and the newly created Repubblica Sociale Italiana, which vowed to continue fighting alongside the Germans. Those who sided with the King were interned in concentration camps and detained in dismal conditions until the end of the war, while those who opted for the Fascist dictator were allowed to go on with their lives, although under strict surveillance by the Kempeitai.

The Italian concession of Tientsin was occupied by Japanese troops with no resistance from its garrison. The Social Republic of Italy later formally gave it to the Japanese puppet Reorganized National Government of the Republic of China.

The news of Italy's surrender did not reach the crew members of the three Italian submarines Giuliani, Cappellini and Torelli travelling to Singapore, then occupied by Japan, to take a load of rubber, tin and strategic materials bound for Italy and Germany's war industry. All the officers and sailors on board were arrested by the Japanese army, and after a few weeks of detention the vast majority of them chose to side with Japan and Germany. The Kriegsmarine assigned new officers to the three units, who were renamed as U-boat U.IT.23, U.IT.24 and U.IT.25, taking part in German war operations in the Pacific until the Giuliani was sunk by the British submarine HMS Tally-ho in February 1944 and the other two vessels were taken over by the Japanese Imperial Navy upon Germany's surrender in 1945.

Alberto Tarchiani, an anti-fascist journalist and activist, was appointed as Ambassador to Washington by the cabinet of Badoglio, which acted as provisional head of the Italian government pending the occupation of the country by the Allied forces. On his suggestion, Italy issued a formal declaration of war on Japan on 14 July 1945.[104]

As early as of May 1945, the Italian destroyer Carabiniere had been prepared and refitted with a new radar and camouflage scheme to operate in the Indian and Pacific Ocean against the Japanese Empire, in collaboration with the Allies. Departing under the command of captain Fabio Tani, after a troublesome voyage the Italian crew reached their new base in Trincomalee. By August 1945, the Carabiniere had undertaken 38 missions of anti-aircraft and anti-submarine escort to British warships and SAR operations. They thoroughly impressed Admiral Arthur Power of the Eastern Fleet during combat and in defending the fleet against kamikaze attacks, and he offered captain Tani a golden watch with 38 rubies, one for each mission, as a prize for their valour. Captain Tani kindly declined, and requested that an Italian POW for each ruby be released instead, which was granted by the Admiral.[105]

A further purpose of the Italian declaration of war on Japan was to persuade the Allies that the new government of Italy deserved to be invited to the San Francisco Peace Conference, as a reward for its co-belligerence.However, the British Prime Minister Churchill and John Foster Dulles were resolutely against the idea, and so Italy's new government was left out of the Conference.

Italy and Japan negotiated the resumption of their respective diplomatic ties after 1951, and later signed several bilateral agreements and treaties.[106]

Casualties

Nearly four million Italians served in the Italian Army during the Second World War and nearly half a million Italians (including civilians) lost their lives between June 1940 and May 1945.

The official Italian government accounting of World War II 1940–45 losses listed the following data:

- Total military dead and missing from 1940 to 1945: 291,376

- Losses prior to the Armistice of Cassibile in September 1943: 204,346 (66,686 killed, 111,579 missing, 26,081 died of disease)

- Losses after the Armistice: 87,030 (42,916 killed, 19,840 missing, 24,274 died of disease). Military losses in Italy after the September 1943 Armistice included 5,927 with the Allies, 17,488 Italian resistance movement fighters and 13,000 Italian Social Republic (RSI) Fascist forces.[107]

- Losses by branch of service:

- Army 201,405

- Navy 22,034

- Air Force 9,096

- Colonial Forces 354

- Chaplains 91

- Fascist militia 10,066

- Paramilitary 3,252

- Not indicated 45,078

- Military losses by theatre of war:

- Italy 74,725 (37,573 post armistice)

- France 2,060 (1,039 post armistice)

- Germany 25,430 (24,020 post armistice)

- Greece, Albania and Yugoslavia 49,459 (10,090 post armistice)

- Soviet Union 82,079 (3,522 post armistice)

- Africa 22,341 (1,565 post armistice)

- At sea 28,438 (5,526 post armistice)

- Other and unknown 6,844 (3,695 post armistice).

Prisoner-of-war losses are included with military losses mentioned above.

The members in the Roll of Honor of the World War II they amount to a total of 319,207 deaths:[108]

- Army 246,432;

- Navy 31,347;

- Air Force 13,210;

- Partisan formations 15,197;

- RSI armed forces 13,021.

Civilian losses totalled 153,147 (123,119 post armistice) including 61,432 (42,613 post armistice) in air attacks.[109] A brief summary of data from this report can be found online.[110]

In addition, deaths of African soldiers conscripted by Italy were estimated by the Italian military to be 10,000 in the 1940–41 East African Campaign.[111]

Civilian losses as a result of the fighting in Italian Libya were estimated by an independent Russian journalist to be 10,000.[112]

Included in total are 64,000 victims of Nazi reprisals and genocide, including 30,000 POWs and 8,500 Jews[113] Russian sources estimated the deaths of 28,000 of the 49,000 Italian prisoners of war in the Soviet Union (1942–1954).[114]

The genocide of Roma people killed 1,000 persons.[115] Jewish Holocaust victims totalled 8,562 (including Libya).[116]

After the armistice with the Allies, some 650,000 members of the Italian armed forces who refused to side with the occupying Germans were interned in concentration and labour camps. Of these, around 50,000 died while imprisoned or in transit.[117] A further 29,000 died in armed struggles against the Germans while resisting capture immediately following the armistice.[117]

Aftermath

The 1947 Treaty of Peace with Italy spelled the end of the Italian colonial empire, along with other border revisions. The 1947 Paris Peace Treaties compelled Italy to pay $360,000,000 (US dollars at 1938 prices) in war reparations: $125,000,000 to Yugoslavia, $105,000,000 to Greece, $100,000,000 to the Soviet Union, $25,000,000 to Ethiopia and $5,000,000 to Albania. Italy also agreed to pay £1,765,000 to Greek nationals whose property in Italian territory had been destroyed or seized during the war.[118] In the 1946 Italian constitutional referendum, the Italian monarchy was abolished, having been associated with the deprivations of the war and Fascist rule. Unlike in Germany and Japan, no war crimes tribunals were held for Italian military and political leaders, though the Italian resistance summarily executed some of them, including Mussolini, at the end of the war.

Controversies of historiography

Allied press reports of Italian military prowess in the Second World War were almost always dismissive. British wartime propaganda trumpeted the destruction of the Italian 10th Army by a significantly smaller British force during the early phase of the North African Campaign.[119][120] The propaganda from this Italian collapse, which was designed to boost British morale during a bleak period of the war, left a lasting impression.[121] The later exploits of Rommel and German accounts of events tended to disparage their Italian allies and downplay their contributions; these German accounts were used as a primary source for the Axis side by English-language historians after the war.[122][123] Kenneth Macksey wrote in 1972 that after the split in the Italian state and the reinforcement of fascist Italy by German troops, "the British threw out the Italian Chicken only to let in the German Eagle", for example.[124][nb 11]. Many military historians that contributed to this dismissive and offensive judgement, such as Basil Liddell Hart, were clearly influenced by German propaganda. Liddell Hart, who considered Italian people racially inferior to Germans,[127] went so far as to express his appreciation for Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring, who had committed atrocious war crimes during the German occupation of Italy, and even lobbied to have him released from prison.[128]

James Sadkovich, Peter Haining, Vincent O'Hara, Ian Walker and others have attempted to reassess the performance of the Italian forces. Many previous authors used only German or British sources, not considering the Italian ones, hampered by the few Italian sources being translated into English.[129] Contemporary British reports ignored an action of Bir El Gobi, where a battalion of Giovani Fascisti held up the 11th Indian Infantry Brigade and destroyed a dozen tanks of the 22nd Armoured Brigade. Sadkovich, Walker and others have found examples of actions where Italian forces were effective, yet rarely discussed by most histories.[130][131][132][133] During the Tunisian campaign, where Italian units were involved in most encounters, such as the battles of Kasserine Pass, Mareth, Akarit and Enfidaville, it was observed by General Alexander, "...the Italians fought particularly well, outdoing the Germans in line with them".[134] Rommel also conceded praise on several occasions.[nb 12] Other times, German mistakes were blamed on Italians,[139] or the Germans left the Italians in hopeless situations where failure was unavoidable.[nb 13] Questionable German advice, broken promises and security lapses had direct consequences at the Battle of Cape Matapan, in the convoy war and North Africa.[141] According to Sadkovich, Rommel often retreated leaving immobile infantry units exposed, withdrew German units to rest even though the Italians had also been in combat, would deprive the Italians of their share of captured goods, ignore Italian intelligence, seldom acknowledge Italian successes and often resist formulation of joint strategy.[142][143] Alan J.Levine, an author who has also extensively worked with Italian sources, points out that while Allied efforts to choke off Rommel's supply lines were eventually successful and played the decisive role in the Allied victory in Africa, the Italians who defended it, especially navy commanders, were not feeble-minded or incompetent at all.[144] He criticises Rommel for ignoring the good advice of Italians during the Crusader Offensive (although he also presents a positive picture of the Field Marshal in general),[145] and in review of Sadkovich's work The Italian Navy in World War II, criticises it for being unreliable and recommends Bragadin and the Italian official history instead.[146] Gerhard L.Weinberg, in his 2011 George C. Marshall Lecture "Military History – Some Myths of World War II" (2011), complained that "there is far too much denigration of the performance of Italy's forces during the conflict."[147]

In addition, Italian 'cowardice' did not appear to be more prevalent than the level seen in any army, despite claims of wartime propaganda.[149] Ian Walker wrote:

....it is perhaps simplest to ask who is the most courageous in the following situations: the Italian carristi, who goes into battle in an obsolete M14 tank against superior enemy armour and anti-tank guns, knowing they can easily penetrate his flimsy protection at a range where his own small gun will have little effect;[nb 14] the German panzer soldier or British tanker who goes into battle in a Panzer IV Special or Sherman respectively against equivalent enemy opposition knowing that he can at least trade blows with them on equal terms; the British tanker who goes into battle in a Sherman against inferior Italian armour and anti-tank guns, knowing confidently that he can destroy them at ranges where they cannot touch him. It would seem clear that, in terms of their motto Ferrea Mole, Ferreo Cuore, the Italian carristi really had "iron hearts", even though as the war went on their "iron hulls" increasingly let them down.

— Walker[151]

The problems that stand out to the vast majority of historians pertain to Italian strategy and equipment. Italian equipment was, in general, not up to the standard of either the Allied or the German armies.[41] An account of the defeat of the Italian 10th Army noted that the incredibly poor quality of the Italian artillery shells saved many British soldiers' lives.[152] More crucially, they lacked suitable quantities of equipment of all kinds and their high command did not take necessary steps to plan for most eventualities.[153] This was compounded by Mussolini's assigning unqualified political favourites to key positions. Mussolini also dramatically overestimated the ability of the Italian military at times, sending them into situations where failure was likely, such as the invasion of Greece.[154]

Historians have long debated why Italy's military and its Fascist regime were so remarkably ineffective at an activity - war - that was central to their identity. MacGregor Knox says the explanation, "was first and foremost a failure of Italy's military culture and military institutions."[155] James Sadkovich gives the most charitable interpretation of Italian failures, blaming inferior equipment, overextension, and inter-service rivalries. Its forces had "more than their share of handicaps."[156] Donald Detwiler concludes that, "Italy's entrance into the war showed very early that her military strength was only a hollow shell. Italy's military failures against France, Greece, Yugoslavia and in the African Theatres of war shook Italy's new prestige mightily."[157]

See also

- Black Brigades

- Italian Army equipment in World War II

- Italian Campaign (World War II), Allied operations in and around Italy, from 1943 to the end of the war in Europe

- Italian war crimes

- List of World War II battles

- Royal Italian Army

- Royal Italian Navy

- Royal Italian Air Force

- MVSN (Blackshirts)

- North African campaign timeline

- Treaty of Peace with Italy, 1947

- Paris Peace Treaties, 1947

Notes

Footnotes

- The decision to continue with a front-line biplane fighter, due to the success of the highly manoeuvrable Fiat CR.32 during the Spanish Civil war was probably one of the most glaring strategic oversights. Another was the mistaken belief that fast bombers need no fighter escort, particularly modern aircraft with radar support.[42]

- Italian doctrine envisaged a blitzkrieg style approach as early as 1936-8, considerably beyond what most theorists discerned at the time. This stressed massed armour, massed and mobile artillery, action against enemy flanks, deep penetration and exploitation, and the 'indirect' approach. Their manuals envisioned M tanks as the core, P tanks as the mobile artillery and reserves for the 'Ms' and L tanks. These were to be combined with fast (celere) infantry divisions and forward anti-tank weapons. The Italians were never able to build the armoured divisions described in their manuals – although they often attempted to mass what they had to make up for the poor performance of some pieces.[43]

- This was being expedited through the conversion of two passenger liners and the scavenging of parts from other vessels. The SS Roma, converted into the Aquila, received 4-shaft turbine engines scavenged from the unfinished light cruisers Cornelio Silla and Paolo Emilio. She was to have a maximum complement of 51 Reggiane Re.2001 fighters. The decision to build carriers came late. The Aquila was virtually ready by the time of the armistice with the Allies in 1943. She was captured by the Germans, who scuttled her in 1945.[47]

- Fiat G.55 Centauro, Macchi C.205, & Reggiane Re.2005; Italian fighters built around the Daimler-Benz DB 605 engine.[47]

- For example: the Fiat G55 Centauro received much German interest and was defined by Oberst Petersen, advisor to Goering, as the "best Axis fighter" and the Macchi C.205 "Veltro" fighter has been argued by many to be the best Italian fighter (and one of the best overall) of the war.

- The M13/40s and M14/41s were not (initially) obsolete when they entered service in late 1940/1941. Their operators (in the form of the Ariete and Littoro divisions) met with much unaccredited success. Yet they became obsolete as the war progressed. It was necessary to maintain production and they suffered unduly as a result of the Italian's inability to produce a suitable successor in time and in numbers.[50][51][52]

- In light of the economic difficulties it was proposed, in 1933, by Marshal Italo Balbo to limit the number of divisions to 20 and ensure that each was fully mobile for ready response, equipped with the latest weaponry and trained for amphibious warfare. The proposal was rejected by Mussolini (and senior figures) who wanted large numbers of divisions to intimidate opponents.[60] To maintain the number of divisions, each became binary, consisting of only two regiments, and therefore equating to a British brigade in size. Even then, they would often be thrown into battle with an under strength complement.

- The French and British, for their part had caused Italy a long list of grievances since during WWI through the extraction of political and economic concessions and the blockading of imports.[67][68] Aware of Italy's material and planning deficiencies leading up to WWII, and believing that Italy's entry into the war on the side of Germany was inevitable, the English blockaded German coal imports from 1 March 1940 in an attempt to bring Italian industry to a standstill.[69] The British and the French then began amassing their naval fleets (to a twelve-to-two superiority in capital ships over the Regia Marina) both in preparation and provocation.[70] They thought wrongly that Italy could be knocked out early, underestimating its determination. Prior to this, from 10 September 1939, the Italians made several attempts to intermediate peace. While Hitler was open to it, the French were not responsive and the British only invited the Italians to change sides. For Mussolini, the risks of staying out of the war were becoming greater than those for entering.[69]

- Graziani believed the British were over 200,000 strong.[78]

- Walker states[87] that the Greeks had assembled 250,000 men against 150,000 Italians; Bauer[88] states that by 12 November, General Papagos had at the front over 100 infantry battalions fighting in terrain to which they were accustomed, compared with less than 50 Italian battalions.

- Other examples: Bishop and Warner (2001) – "It was Germany's misfortune to be allied to Italy.....the performance of most Italian infantry units risable.....could be relied on to fold like a house of cards.....dash and elan but no endurance";[125] Morrison (1984) – "There was also the Italian fleet to guard against, on paper, but the 'Dago Navy' had long been regarded by British tars as a huge joke".[126]

- Writing about the fighting at the First Battle of El Alamein Rommel stated: "The Italians were willing, unselfish and good comrades in the frontline. There can be no disputing that the achievement of all the Italian units, especially the motorised elements, far outstripped any action of the Italian Army for 100 years. Many Italian generals and officers earned our respect as men as well as soldiers".[135] During the Second Battle of El Alamein the 7th Bersaglieri Regiment exhibited a strong regimental spirit in the fight for Hill 28 that impressed Rommel to comment positively.[136] On a plaque dedicated to the Bersaglieri that fought at Mersa Matruh and Alamein, Rommel wrote: "The German soldier has impressed the world, however the Italian Bersaglieri has impressed the German soldier."[137] Describing the behaviour of the 'Ariete Armoured division' during the last phases of the battle of El Alamein, Rommel also wrote: Enormous dust-clouds could be seen south and south-east of headquarters [of the DAK], where the desperate struggle of the small and inefficient Italian tanks of XX Corps was being played out against the hundred or so British heavy tanks which had come round their open right flank. I was later told by Major von Luck, whose battalion I had sent to close the gap between the Italians and the Afrika Korps, that the Italians, who at that time represented our strongest motorised force, fought with exemplary courage. Tank after tank split asunder or burned out, while all the time a tremendous British barrage lay over the Italian infantry and artillery positions. The last signal came from the Ariete at about 15.30 hours: "Enemy tanks penetrated south of Ariete. Ariete now encircled. Location 5 km north-west Bir el Abd. Ariete tanks still in action." [...] In the Ariete we lost our oldest Italian comrades, from whom we had probably always demanded more than they, with their poor armament, had been capable of performing.[138]

- Ripley asserted: "The Italians supplied the bulk of the Axis troops fighting in North Africa, and too often the German Army unfairly ridiculed Italian military effectiveness either due to its own arrogance or to conceal its own mistakes and failures. In reality, a significant number of Italian units fought skilfully in North Africa, and many "German" victories were the result of Italian skill-at-arms and a combined Axis effort."[140]

- Bierman and Smith[150] documented multiple instances of Italian armour advancing against such odds, including when a disproportionate number of their contingent were knocked out.

- The phrase "prisoner in the Mediterranean" had been used in parliament as early as 30 March 1925, by the naval minister Admiral Paolo Thaon di Revel. Revel was arguing for naval funding to receive priority over army funding.[18]

Citations

- MacGregor Knox. Mussolini unleashed, 1939–1941: Politics and Strategy in Fascist Italy's Last War. Edition of 1999. Cambridge, England, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1999. pp. 122–123.

- "Italy declares war on Germany". History.com. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- Gianni Oliva, I vinti e i liberati: 8 settembre 1943-25 aprile 1945 : storia di due anni, Mondadori, 1994.

- Mack Smith 1982, p. 170.

- Martel 1999, pp. 184, 198.

- Bideleux & Jeffries 1998, p. 467.

- Bell 1997, pp. 70–71.

- Martel 1999, p. 198.

- Preston 1999, pp. 21–22.

- Preston 1996, pp. 22, 50–51.

- Bell 1997, pp. 73–74, 154.

- Grenville 2001, p. 211.

- Atkin 2011, p. 22.

- Burgwyn 1997, pp. 182–183.

- Clark 2005, p. 243.

- Bell 1997, p. 72.

- Salerno 2002, pp. 105–06.

- Knox 2000, p. 8.

- Martel 1999, p. 67.

- Clark 2005, p. 244.

- Bell 1997, pp. 72–73.

- Harvey 2009, p. 96.

- Mallett 2003, p. 9.

- Zabecki 1999, p. 1353.

- Bell 1997, pp. 73, 291.

- Weinberg 1994, p. 73.

- Bell 1997, p. 291.

- Walker (2003), p. 19

- Steinberg (1990), pp. 189, 191

- Walker (2003) p. 12

- Bauer (2000), p. 231

- Walker (2003), p. 26

- Beevor (2006) pp. 45, 47, 88–89, 148, 152, 167, 222–4, 247, 322–6, 360, 405–6, 415

- Walker (2003), p. 17

- Bonner and Wiggin (2006), p. 84

- Cliadakis 1974, pp. 178–80.

- Mallett 1997, p. 158.

- Sadkovich 1989, p. 30.

- Jensen 1968, p. 550.

- Eden & Moeng (Eds.) (2002), pp. 680–681

- Bierman & Smith (2002), pp. 13–14

- Walker (2003) p. 22

- Sadkovich (1991) pp. 290–91; and references therein

- Walker (2003) pp. 30–53

- Sadkovich (1991) pp. 287–291

- Steinberg (1990), p. 189

- Bauer (2000), p. 146

- Eden & Moeng (Eds.) (2002), pp. 684–685, 930, 1061

- Bishop (1998) p. 18

- Bishop (1998) pp. 17–18

- Walker (2003) p. 48

- Sadkovich (1991) p. 290

- Walker (2003) p. 109

- Bishop (1998) pp. 149, 164

- Games, Warlord (2013). Bolt Action: Armies of Italy and the Axis. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 27. ISBN 9781782009672.

- Henderson, Jim. "Autoblinda". Commando Supremo: Italy at War website. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- Nolan, Cathal (2010). The Concise Encyclopedia of World War II. ABC-CLIO. p. 269. ISBN 9780313365270.

- Walker (2003) pp. 112-13

- Mussolini, Peter Neville, p. 140, Routledge, 2004 ISBN 0-415-24989-9

- Walker (2003) p. 23

- Walker (2003) p. 21

- Bauer (2000), pp. 96, 493

- Walker (2003) p. 11

- Walker (2003) p. 20

- Bauer (2000), pp. 90–95

- Axelrod, Alan (2008). The Real History of World War II. Sterling Publishing. p. 180. ISBN 978-1-4027-4090-9.

- O'Hara (2009) p. 9

- Nelson Page (1920) chapt. XXIII

- O'Hara (2009) p. 3

- O'Hara (2009) p. 12

- Walker (2003) p. 25

- Badoglio, Pietro (1946). L'Italia nella seconda guerra mondiale [Italy in the Second World War] (in Italian). Milan: Mondadori. p. 37.

- "Voices of World War II, 1937–1945". Retrieved 14 August 2008.

- Italy and the Jews – Timeline by Elizabeth D. Malissa

- Crociani, Piero; Battistelli, Pier Paolo (2013). Italian Navy & Air Force Elite Units & Special Forces 1940–45. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781780963723.

- Cecini, Giovanni (2016). I generali di Mussolini (in Italian). Newton Compton Editori. ISBN 9788854198685.

- Bauer (2000), p. 93

- Bauer (2000), p. 113

- Bauer (2000), p. 95

- Jowett, Philip S. (2001). The Italian Army 1940–1945: Africa 1940–43. Men-at-Arms. Vol. 2. Osprey. p. 11. ISBN 1-85532-865-8.

- Carrier, Richard (March 2015). "Some Reflections on the Fighting Power of the Italian Army in North Africa, 1940–1943". War in History. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 22 (4): 503–528. doi:10.1177/0968344514524395. ISSN 0968-3445. S2CID 159518524.

- Bauer 2000, p. 118

- Wilmott 1944, p. 65

- Bauer 2000, p. 121

- Zabecki, David (2015). World War II in Europe. Taylor & Francis. p. 728. ISBN 9781135812423.

- Bauer 2000, p. 99

- Walker (2003), p. 28

- Bauer (2000), p. 105

- James J. Sadkovich. "Understanding Defeat." Journal of Contemporary History, Volume 24, 1989. p. 38. Citing:' SME/US, Grecia, I, 943'.

- Stockings, Craig; Hancock, Eleanor (2013). Swastika over the Acropolis: Re-interpreting the Nazi Invasion of Greece in World War II. pp. 45, 87-88.

- Hitler, Adolf, Speech to the Reichstag on 4 May 1941.

- Quartermaine 2000, p. 9

- Quartermaine 2000, p. 11

- Quartermaine 2000, pp. 11–12

- Tompkins, Peter, Italy Betrayed, Simon & Schuster (1966)

- O'Hara and Cernuschi (2009), p. 46

- O'Hara and Cernuschi (2009), p. 47

- O'Reilly, Charles T., Forgotten battles: Italy's war of liberation, 1943–1945. Illustrated ed., Publisher: Lexington Books, Year: 2001, ISBN 0-7391-0195-1, p. 14

- O'Reilly, Charles T., Forgotten battles: Italy's war of liberation, 1943–1945. Illustrated ed., Publisher: Lexington Books, Year: 2001, ISBN 0-7391-0195-1, p. 96

- "Channel 4 – History – Warlords: Churchill". Retrieved 14 August 2008.