Pinyin

Hanyu Pinyin (simplified Chinese: 汉语拼音; traditional Chinese: 漢語拼音; pinyin: Hànyǔ pīnyīn), or simply pinyin, is the most common romanization system for Standard Chinese.[lower-alpha 1] In official documents, it is referred to as the Chinese Phonetic Alphabet.[1] It is used in official contexts where Standard Chinese is an official language: Greater China and Singapore, as well as by the United Nations and in other international contexts. It is used principally to teach Mandarin, normally written with Chinese characters, to students already familiar with the Latin alphabet. The system uses four diacritics to denote the tones of Standard Chinese, though these are often omitted in various contexts, such as when spelling Chinese names in non-Chinese texts, and writing words from non-Chinese languages in Chinese-language texts. Hanyu Pinyin is also used in various input methods to type Chinese characters on computers, some Chinese dictionaries use it to arrange entries. The word 汉语; 漢語; Hànyǔ literally means 'Han language' (i.e. the Chinese language), while 拼音; pīnyīn means 'spelled sounds'.[2]

| Hanyu Pinyin 汉语拼音; 漢語拼音 | |

|---|---|

| Script type | romanization |

| Created | 1950s |

Time period |

|

| Languages | Standard Chinese |

| Pinyin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

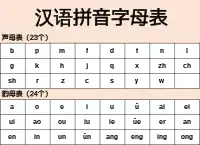

Table of Hanyu Pinyin syllables, which includes 23 initials (top) and 24 finals (bottom) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 拼音 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Scheme for the Chinese Phonetic Alphabet | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 汉语拼音方案 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 漢語拼音方案 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sinitic (Chinese) romanization |

|---|

| Mandarin |

| Wu |

| Yue |

| Min |

| Gan |

| Hakka |

| Xiang |

| Polylectal |

| See also |

Hanyu Pinyin was developed in the 1950s, led by a group of Chinese linguists including Wang Li, Lu Zhiwei, Li Jinxi, Luo Changpei[3] and Zhou Youguang,[4] who based their work in part on earlier romanization systems. The system was originally promulgated at the Fifth Session of the First National People's Congress in 1958, and has seen several rounds of revisions since.[5] The International Organization for Standardization propagated Hanyu Pinyin as ISO 7098 in 1982,[6] and the United Nations began using it in 1986.[4] Attempts to make Hanyu Pinyin standard in Taiwan occurred in 2002 and 2009, and while the system has been official since the latter attempt,[7][8] [9] Taiwan largely has no standardized spelling system. Moreover, some cities, businesses, and organizations, especially in the south, did not accept efforts to introduce Hanyu Pinyin for political reasons, as it could represent a push for further integration with the PRC. Consequently, it remains one of several rival romanization systems in use, along with Wade–Giles and the autochthonous Tongyong Pinyin.[10]

When a non-native writing system is designed to write a language, certain compromises may be made in an attempt to aid non-native speakers in reproducing the sounds of the target language. Native speakers of English tend to produce fairly accurate pronunciations when reading pinyin, with exceptions usually occurring with phonemes not generally found in English, spelled with characters usually associated with divergent English pronunciations:

| z | /ts/ | c | /tsʰ/ | ||||||

| x | /ɕ/ | j | /tɕ/ | q | /tɕʰ/ | ||||

| zh | /ʈʂ/ | ch | /ʈʂʰ/ | r | /ɻ/ |

In this system, the correspondence between the Latin letters and the sound is sometimes idiosyncratic, though not necessarily more so than the way the Latin script is employed in other languages. For example, the aspiration distinction between b, d, g and p, t, k is similar to that of these syllable-initial consonants in English (in which the two sets are, however, also differentiated by voicing), but not to that of French. Letters z and c also have that distinction, pronounced as [ts] and [tsʰ] (which is reminiscent of these letters being used to represent the phoneme /ts/ in German and in Slavic languages written in the Latin script, respectively). From s, z, c come the digraphs sh, zh, ch by analogy with English sh, ch. Although this analogical use of digraphs introduces the novel combination zh}, it is internally consistent in how the two series are related. In the x, j, q series, the pinyin use of x is similar to its use in Portuguese, Galician, Catalan, Basque, and Maltese to represent /ʃ/; the pinyin q is close to its value of /c͡ç/ in Albanian, though to the untrained ear both pinyin and Albanian pronunciations may sound similar to the ch. Pinyin vowels are pronounced in a similar way to vowels in Romance languages.

The pronunciations and spellings of Chinese words are generally given in terms of initials and finals, which represent the language's segmental phonemic portion, rather than letter by letter. Initials are initial consonants, whereas finals are all possible combinations of medials (semivowels coming before the vowel), a nucleus vowel, and coda (final vowel or consonant).

History

Before 1949

In 1605, the Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci published Xizi Qiji (西字奇蹟; Xīzì Qíjì; Hsi-tzu Ch'i-chi; 'Miracle of Western Letters') in Beijing.[11] This was the first book to use the Roman alphabet to write the Chinese language. Twenty years later, another Jesuit in China, Nicolas Trigault, issued his 《西儒耳目資》; Xī Rú Ěrmù Zī; Hsi Ju Erh-mu Tzu; 'Aid to the Eyes and Ears of Western Literati') at Hangzhou.[12] Neither book had much immediate impact on the way in which Chinese thought about their writing system, and the romanizations they described were intended more for Westerners than for the Chinese.[13]

One of the earliest Chinese thinkers to relate Western alphabets to Chinese was 17th century scholar-official Fang Yizhi (方以智; Fāng Yǐzhì; Fang I-chih; 1611–1671).[14]

The first late Qing reformer to propose that China adopt a system of spelling was Song Shu (1862–1910). A student of the great scholars Yu Yue and Zhang Taiyan, Song had been to Japan and observed the stunning effect of the kana syllabaries and Western learning there. This galvanized him into activity on a number of fronts, one of the most important being reform of the script. While Song did not himself actually create a system for spelling Sinitic languages, his discussion proved fertile and led to a proliferation of schemes for phonetic scripts.[13]

Wade–Giles

The Wade–Giles system was produced by Thomas Wade in 1859, and further improved by Herbert Giles in the Chinese–English Dictionary of 1892. It was popular and used in English-language publications outside China until 1979.[15]

Sin Wenz

In the early 1930s, Chinese Communist Party leaders trained in Moscow introduced a phonetic alphabet using Roman letters which had been developed in the Soviet Oriental Institute of Leningrad and was originally intended to improve literacy in the Russian Far East.[16][note 1] This Sin Wenz or "New Writing"[17] was much more linguistically sophisticated than earlier alphabets, but with the major exception that it did not indicate tones of Chinese.[18]

In 1940, several thousand members attended a Border Region Sin Wenz Society convention. Mao Zedong and Zhu De, head of the army, both contributed their calligraphy (in characters) for the masthead of the Sin Wenz Society's new journal. Outside the party, other prominent supporters included Sun Yat-sen's son, Sun Fo, the country's most prestigious educator Cai Yuanpei, leading educational reformer Tao Xingzhi, and Lu Xun. Over thirty journals soon appeared written in Sin Wenz, plus large numbers of translations, biographies of figures such as Abraham Lincoln, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, and Charlie Chaplin, some contemporary Chinese literature, and a variety of textbooks. In 1940, the movement reached an apex when Mao's Border Region Government declared that the Sin Wenz had the same legal status as traditional characters in government and public documents. Many educators and political leaders looked forward to the day when they would be universally accepted and completely replace Chinese characters. Opposition arose, however, because the system was less well adapted to writing regional languages, and therefore would require learning Mandarin. Sin Wenz fell into relative disuse during the following years.[19]

Yale romanization

In 1943, the U.S. military engaged Yale University to develop a romanization of Mandarin Chinese for its pilots flying over China. The resulting system is very close to pinyin, but does not use English letters in unfamiliar ways; for example, pinyin x for [ɕ] is written as sy in the Yale system. The medial semivowels are written with y and w, instead of the pinyin i and u; apical vowels (syllabic consonants) are written with r or z. Accent marks are similarly used to indicate tone.

Emergence of Hanyu Pinyin

Pinyin was created by a group of Chinese linguists, including Wang Li, Lu Zhiwei, Li Jinxi, Luo Changpei,[3] as well as Zhou Youguang who was an economist,[4] as part of a Chinese government project in the 1950s. Zhou, often called "the father of pinyin",[4][20][21][22] worked as a banker in New York when he decided to return to China to help rebuild the country after the People's Republic was established. Initially, Mao Zedong considered the development of a new, wholly-romanized writing system for Chinese, but during his first official visit to the Soviet Union in 1949, Joseph Stalin convinced him to maintain the existing system.[23] Zhou became an economics professor in Shanghai, and when China's Ministry of Education created a "Committee for the Reform of the Chinese Written Language" in 1955, Premier Zhou Enlai assigned him the task of developing a new romanization system, despite the fact that he was not a linguist by trade.[4]

Hanyu Pinyin was based on several existing systems, including Gwoyeu Romatzyh from 1928, Latinxua Sin Wenz from 1931, and the diacritic markings from zhuyin.[24] "I'm not the father of pinyin", Zhou said years later; "I'm the son of pinyin. It's [the result of] a long tradition from the later years of the Qing dynasty down to today. But we restudied the problem and revisited it and made it more perfect."[25]

An initial draft was authored in January 1956 by Ye Laishi, Lu Zhiwei and Zhou Youguang.[26] A revised Pinyin scheme was proposed by Wang Li, Lu Zhiwei and Li Jinxi, and became the main focus of discussion among the group of Chinese linguists in June 1956, forming the basis of Pinyin standard later after incorporating a wide-range of feedback and further revisions.[3][26][27] The first edition of Hanyu Pinyin was approved and officially adopted at the Fifth Session of the 1st National People's Congress on February 11, 1958. It was then introduced to primary schools as a way to teach Standard Chinese pronunciation and used to improve the literacy rate among adults.[28]

During the height of the Cold War the use of pinyin system over the Yale romanization outside of China was regarded as a political statement or identification with the communist Chinese regime.[29] Beginning in the early 1980s, Western publications addressing Mainland China began using the Hanyu Pinyin romanization system instead of earlier romanization systems;[30] this change followed the normalization of diplomatic relations between the United States and the PRC in 1979.[31][32] In 2001, the PRC Government issued the National Common Language Law, providing a legal basis for applying pinyin.[28] The current specification of the orthographic rules is laid down in the National Standard GB/T 16159–2012.[33]

Initials and finals

Unlike European languages, clusters of letters —initials (声母; 聲母; shēngmǔ) and finals (韵母; 韻母; yùnmǔ)— and not consonant and vowel letters, form the fundamental elements in pinyin (and most other phonetic systems used to describe the Han language). Every Mandarin syllable can be spelled with exactly one initial followed by one final, except for the special syllable er or when a trailing -r is considered part of a syllable (a phenomenon known as erhua). The latter case, though a common practice in some sub-dialects, is rarely used in official publications.

Even though most initials contain a consonant, finals are not always simple vowels, especially in compound finals (复韵母; 複韻母; fùyùnmǔ), i.e. when a "medial" is placed in front of the final. For example, the medials [i] and [u] are pronounced with such tight openings at the beginning of a final that some native Chinese speakers (especially when singing) pronounce yī (衣, clothes, officially pronounced /í/) as /jí/ and wéi (围; 圍, to enclose, officially pronounced /uěi/) as /wěi/ or /wuěi/. Often these medials are treated as separate from the finals rather than as part of them; this convention is followed in the chart of finals below.

Initials

In each cell below, the bold letters indicate pinyin and the brackets enclose the symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet.

1 y is pronounced [ɥ] (a labial-palatal approximant) before u.

2 The letters w and y are not included in the table of initials in the official pinyin system. They are an orthographic convention for the medials i, u and ü when no initial is present. When i, u, or ü are finals and no initial is present, they are spelled yi, wu, and yu, respectively.

The conventional lexicographical order (excluding w and y), derived from the zhuyin system ("bopomofo"), is:

b p m f d t n l g k h j q x zh ch sh r z c s

According to Scheme for the Chinese Phonetic Alphabet, zh, ch, and sh can be abbreviated as ẑ, ĉ, and ŝ (z, c, s with a circumflex). However, the shorthand is rarely used, due to difficulty of computer input: the specific characters are encountered mainly in Esperanto keyboard layouts.

Finals

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

| Close |

| |||||

| Close-mid | ||||||

| Open-mid | ||||||

| Open | ||||||

In each cell below, the first line indicates IPA, the second indicates pinyin for a standalone (no-initial) form, and the third indicates pinyin for a combination with an initial. Other than finals modified by an -r, which are omitted, the following is an exhaustive table of all possible finals.1[34]

The only syllable-final consonants in Standard Chinese are -n, -ng, and -r, the last of which is attached as a grammatical suffix. A Chinese syllable ending with any other consonant either is from a non-Mandarin language (a southern Chinese language such as Cantonese, reflecting final consonants in Old Chinese), or indicates the use of a non-pinyin romanization system, such as one that uses final consonants to indicate tones.

| Rime | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∅ | -e/-o | -a | -ei | -ai | -ou | -ao | -en | -an | -eng | -ang | er | |||||

| Medial | ∅ | [ɨ] -i | [ɤ] e -e | [a] a -a |

[ei̯] ei -ei | [ai̯] ai -ai |

[ou̯] ou -ou | [au̯] ao -ao |

[ən] en -en | [an] an -an |

[əŋ] eng -eng | [aŋ] ang -ang |

[ɚ] er 1 | |||

| y- -i- |

[i] yi -i | [je] ye -ie | [ja] ya -ia |

[jou̯] you -iu | [jau̯] yao -iao |

[in] yin -in | [jɛn] yan -ian |

[iŋ] ying -ing | [jaŋ] yang -iang |

|||||||

| w- -u- |

[u] wu -u | [wo] wo -uo 3 | [wa] wa -ua |

[wei̯] wei -ui | [wai̯] wai -uai |

[wən] wen -un | [wan] wan -uan |

[wəŋ~ʊŋ] weng -ong | [waŋ] wang -uang |

|||||||

| yu- -ü- |

[y] yu -ü 2 | [ɥe] yue -üe 2 | [yn] yun -ün 2 | [ɥɛn] yuan -üan 2 |

[jʊŋ] yong -iong | |||||||||||

1 For other finals formed by the suffix -r, pinyin does not use special orthography; one simply appends r to the final that it is added to, without regard for any sound changes that may take place along the way. For information on sound changes related to final r, please see Erhua#Rules in Standard Mandarin.

2 ü is written as u after y, j, q, or x.

3 uo is written as o after b, p, m, f, or w.

Technically, i, u, ü without a following vowel are finals, not medials, and therefore take the tone marks, but they are more concisely displayed as above. In addition, ê [ɛ] (欸; 誒) and syllabic nasals m (呒, 呣), n (嗯, 唔), ng (嗯, 𠮾) are used as interjections.

According to Scheme for the Chinese Phonetic Alphabet, ng can be abbreviated with a shorthand of ŋ. However, this shorthand is rarely used due to difficulty of entering them on computers.

The ü sound

An umlaut is placed over the letter u when it occurs after the initials l and n when necessary in order to represent the sound [y]. This is necessary in order to distinguish the front high rounded vowel in lü (e.g. 驴; 驢; 'donkey') from the back high rounded vowel in lu (e.g. 炉; 爐; 'oven'). Tonal markers are added on top of the umlaut, as in lǘ.

However, the ü is not used in the other contexts where it could represent a front high rounded vowel, namely after the letters j, q, x, and y. For example, the sound of the word 鱼/魚 (fish) is transcribed in pinyin simply as yú, not as yǘ. This practice is opposed to Wade–Giles, which always uses ü, and Tongyong Pinyin, which always uses yu. Whereas Wade–Giles needs the umlaut to distinguish between chü (pinyin ju) and chu (pinyin zhu), this ambiguity does not arise with pinyin, so the more convenient form ju is used instead of jü. Genuine ambiguities only happen with nu/nü and lu/lü, which are then distinguished by an umlaut.

Many fonts or output methods do not support an umlaut for ü or cannot place tone marks on top of ü. Likewise, using ü in input methods is difficult because it is not present as a simple key on many keyboard layouts. For these reasons v is sometimes used instead by convention. For example, it is common for cellphones to use v instead of ü. Additionally, some stores in China use v instead of ü in the transliteration of their names. The drawback is that there are no tone marks for the letter v.

This also presents a problem in transcribing names for use on passports, affecting people with names that consist of the sound lü or nü, particularly people with the surname 吕 (Lǚ), a fairly common surname, particularly compared to the surnames 陆 (Lù), 鲁 (Lǔ), 卢 (Lú) and 路 (Lù). Previously, the practice varied among different passport issuing offices, with some transcribing as "LV" and "NV" while others used "LU" and "NU". On 10 July 2012, the Ministry of Public Security standardized the practice to use "LYU" and "NYU" in passports.[35][36]

Although nüe written as nue, and lüe written as lue are not ambiguous, nue or lue are not correct according to the rules; nüe and lüe should be used instead. However, some Chinese input methods (e.g. Microsoft Pinyin IME) support both nve/lve (typing v for ü) and nue/lue.

Approximations to English pronunciation

Most rules given here in terms of English pronunciation are approximations, as several of these sounds do not correspond directly to sounds in English.

Pronunciation of initials

| Pinyin | IPA | English approximation[37] | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| b | [p] | spark | unaspirated p, as in spark |

| p | [pʰ] | pay | strongly aspirated p, as in pit |

| m | [m] | may | as in English mummy |

| f | [f] | fair | as in English fun |

| d | [t] | stop | unaspirated t, as in stop |

| t | [tʰ] | take | strongly aspirated t, as in top |

| n | [n] | nay | as in English nit |

| l | [l] | lay | as in English love |

| g | [k] | skill | unaspirated k, as in skill |

| k | [kʰ] | kay | strongly aspirated k, as in kiss |

| h | [x], [h] | loch | Varies between hat and Scottish loch. |

| j | [tɕ] | churchyard | Alveo-palatal. No equivalent in English, but similar to an unaspirated "-chy-" sound when said quickly. Like q, but unaspirated. Is similar to the English name of the letter G, but curl the tip of the tongue downwards to stick it at the back of the teeth. |

| q | [tɕʰ] | punch yourself | Alveo-palatal. No equivalent in English. Like punch yourself, with the lips spread wide as when one says ee. Curl the tip of the tongue downwards to stick it at the back of the teeth and strongly aspirate. |

| x | [ɕ] | push yourself | Alveo-palatal. No equivalent in English. Like -sh y-, with the lips spread as when one says ee and with the tip of the tongue curled downwards and stuck to the back of the teeth. |

| zh | [ʈʂ] | nurture | Unaspirated ch. Similar to hatching but retroflex, or marching in American English. Voiced in a toneless syllable. |

| ch | [ʈʂʰ] | church | Similar to chin, but retroflex. |

| sh | [ʂ] | shirt | Similar to shoe but retroflex, or marsh in American English. |

| r | [ɻ~ʐ] | ray | No equivalent in English, but similar to a sound between r in reduce and s in measure but with the tongue curled upward against the top of the mouth (i.e. retroflex). |

| z | [ts] | pizza | unaspirated c, similar to something between suds but voiceless, unless in a toneless syllable. |

| c | [tsʰ] | hats | like the English ts in cats, but strongly aspirated, very similar to the Czech, Polish, Esperanto, and Slovak c. |

| s | [s] | say | as in sun |

| w | [w] | way | as in water. Before an e or a it is sometimes pronounced like v as in violin.* |

| y | [j], [ɥ] | yes | as in yes. Before a u, pronounced with rounded lips, as if pronouncing German ü.* |

- * Note on y and w

Y and w are equivalent to the semivowel medials i, u, and ü (see below). They are spelled differently when there is no initial consonant in order to mark a new syllable: fanguan is fan-guan, while fangwan is fang-wan (and equivalent to *fang-uan). With this convention, an apostrophe only needs to be used to mark an initial a, e, or o: Xi'an (two syllables: [ɕi.an]) vs. xian (one syllable: [ɕi̯ɛn]). In addition, y and w are added to fully vocalic i, u, and ü when these occur without an initial consonant, so that they are written yi, wu, and yu. Some Mandarin speakers do pronounce a [j] or [w] sound at the beginning of such words—that is, yi [i] or [ji], wu [u] or [wu], yu [y] or [ɥy],—so this is an intuitive convention. See below for a few finals which are abbreviated after a consonant plus w/u or y/i medial: wen → C+un, wei → C+ui, weng → C+ong, and you → Q+iu.

- ** Note on the apostrophe

The apostrophe (') (隔音符号; 隔音符號; géyīn fúhào; 'syllable-dividing mark') is used before a syllable starting with a vowel (a, o, or e) in a multiple-syllable word, unless the syllable starts the word or immediately follows a hyphen or other dash. For example, 西安 is written as Xi'an or Xī'ān, and 天峨 is written as Tian'e or Tiān'é, but 第二 is written "dì-èr", without an apostrophe.[38] This apostrophe is not used in the Taipei Metro names.[39]

Apostrophes (as well as hyphens and tone marks) are omitted on Chinese passports.[40]

Pronunciation of finals

The following is a list of finals in Standard Chinese, excepting most of those ending with r.

To find a given final:

- Remove the initial consonant. zh, ch, and sh count as initial consonants.

- Change initial w to u and initial y to i. For weng, wen, wei, you, look under ong, un, ui, iu.

- For u (including the ones starting with u) after j, q, x, or y, look under ü.

| Pinyin | IPA | Form with zero initial | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| -i | [ɹ̩~z̩], [ɻ̩~ʐ̩] | (N/A) | -i is a buzzed continuation of the consonant following z-, c-, s-, zh-, ch-, sh- or r-. (In all other cases, -i has the sound of bee; this is listed below.) |

| a | [a] | a | like English father, but a bit more fronted |

| e | [ɤ] ⓘ | e | a back, unrounded vowel (similar to English duh, but not as open). Pronounced as a sequence [ɰɤ]. |

| ai | [ai̯] | ai | like English eye, but a bit lighter |

| ei | [ei̯] | ei | as in hey |

| ao | [au̯] | ao | approximately as in cow; the a is much more audible than the o |

| ou | [ou̯] | ou | as in North American English so |

| an | [an] | an | like British English ban, but more central |

| en | [ən] | en | as in taken |

| ang | [aŋ] | ang | as in German Angst. (Starts with the vowel sound in father and ends in the velar nasal; like song in some dialects of American English) |

| eng | [əŋ] | eng | like e in en above but with ng appended |

| ong | [ʊŋ] | (weng) | starts with the vowel sound in book and ends with the velar nasal sound in sing. Varies between [oŋ] and [uŋ] depending on the speaker. |

| er | [aɚ̯] | er | Similar to the sound in bar in English. Can also be pronounced [ɚ] depending on the speaker. |

| Finals beginning with i- (y-) | |||

| i | [i] | yi | like English bee |

| ia | [ja] | ya | as i + a; like English yard |

| ie | [je] | ye | as i + ê where the e (compare with the ê interjection) is pronounced shorter and lighter |

| iao | [jau̯] | yao | as i + ao |

| iu | [jou̯] | you | as i + ou |

| ian | [jɛn] | yan | as i + an; like English yen. Varies between [jen] and [jan] depending on the speaker. |

| in | [in] | yin | as i + n |

| iang | [jaŋ] | yang | as i + ang |

| ing | [iŋ] | ying | as i + ng |

| iong | [jʊŋ] | yong | as i + ong. Varies between [joŋ] and [juŋ] depending on the speaker. |

| Finals beginning with u- (w-) | |||

| u | [u] | wu | like English oo |

| ua | [wa] | wa | as u + a |

| uo/o | [wo] | wo | as u + o where the o (compare with the o interjection) is pronounced shorter and lighter (spelled as o after b, p, m or f) |

| uai | [wai̯] | wai | as u + ai, as in English why |

| ui | [wei̯] | wei | as u + ei, as in English way |

| uan | [wan] | wan | as u + an |

| un | [wən] | wen | as u + en; as in English won |

| uang | [waŋ] | wang | as u + ang |

| (ong) | [wəŋ] | weng | as u + eng |

| Finals beginning with ü- (yu-) | |||

| ü | [y] ⓘ | yu | as in German über or French lune (pronounced as English ee with rounded lips; spelled as u after j, q or x) |

| üe | [ɥe] | yue | as ü + ê where the e (compare with the ê interjection) is pronounced shorter and lighter (spelled as ue after j, q or x) |

| üan | [ɥɛn] | yuan | as ü + an. Varies between [ɥen] and [ɥan] depending on the speaker (spelled as uan after j, q or x) |

| ün | [yn] | yun | as ü + n (spelled as un after j, q or x) |

| Interjections | |||

| ê | [ɛ] | (N/A) | as in bet |

| o | [ɔ] | (N/A) | approximately as in British English office; the lips are much more rounded |

| io | [jɔ] | yo | as i + o |

Tones

The pinyin system also uses diacritics to mark the four tones of Mandarin. The diacritic is placed over the letter that represents the syllable nucleus, unless that letter is missing (see below).

If the tone mark is written over an i, the tittle above the i is omitted, as in yī.

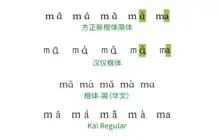

Many books printed in China use a mix of fonts, with vowels and tone marks rendered in a different font from the surrounding text, tending to give such pinyin texts a typographically ungainly appearance. This style, most likely rooted in early technical limitations, has led many to believe that pinyin's rules call for this practice, e.g. the use of a Latin alpha (ɑ) rather than the standard style (a) found in most fonts, or g often written with a single-storey ɡ. The rules of Hanyu Pinyin, however, specify no such practice.[41]: 3.3.4.1:8

- The first tone (flat or high-level tone) is represented by a macron (ˉ) added to the pinyin vowel:

- ā ē ī ō ū ǖ Ā Ē Ī Ō Ū Ǖ

- The second tone (rising or high-rising tone) is denoted by an acute accent (ˊ):

- á é í ó ú ǘ Á É Í Ó Ú Ǘ

- The third tone (falling-rising or low tone) is marked by a caron/háček (ˇ). It is not the rounded breve (˘), though a breve is sometimes substituted due to ignorance or font limitations.

- ǎ ě ǐ ǒ ǔ ǚ Ǎ Ě Ǐ Ǒ Ǔ Ǚ

- The fourth tone (falling or high-falling tone) is represented by a grave accent (ˋ):

- à è ì ò ù ǜ À È Ì Ò Ù Ǜ

- The fifth tone (neutral tone) is represented by a normal vowel without any accent mark:

- a e i o u ü A E I O U Ü

- In dictionaries, neutral tone may be indicated by a dot preceding the syllable; for example, ·ma. When a neutral tone syllable has an alternative pronunciation in another tone, a combination of tone marks may be used: zhī·dào (知道).[42]

Numerals in place of tone marks

Before the advent of computers, many typewriter fonts did not contain vowels with macron or caron diacritics. Tones were thus represented by placing a tone number at the end of individual syllables. For example, tóng is written tong². The number used for each tone is as the order listed above, except the neutral tone, which is either not numbered, or given the number 0 or 5, e.g. ma⁵ for 吗/嗎, an interrogative marker.

| Tone | Tone Mark | Number added to end of syllable in place of tone mark | Example using tone mark | Example using number | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | macron ( ◌̄ ) | 1 | mā | ma1 | ma˥ |

| Second | acute accent ( ◌́ ) | 2 | má | ma2 | ma˧˥ |

| Third | caron ( ◌̌ ) | 3 | mǎ | ma3 | ma˨˩˦ |

| Fourth | grave accent ( ◌̀ ) | 4 | mà | ma4 | ma˥˩ |

| Neutral | none or middle dot before syllable ( ·◌ ) | 5 0 | ma ·ma | ma ma5 ma0 | ma |

Rules for placing the tone mark

Briefly, the tone mark should always be placed by the order—a, o, e, i, u, ü, with the only exception being iu, where the tone mark is placed on the u instead. Pinyin tone marks appear primarily above the nucleus of the syllable, for example as in kuài, where k is the initial, u the medial, a the nucleus, and i the coda. The exception is syllabic nasals like /m/, where the nucleus of the syllable is a consonant, the diacritic will be carried by a written dummy vowel.

When the nucleus is /ə/ (written e or o), and there is both a medial and a coda, the nucleus may be dropped from writing. In this case, when the coda is a consonant n or ng, the only vowel left is the medial i, u, or ü, and so this takes the diacritic. However, when the coda is a vowel, it is the coda rather than the medial which takes the diacritic in the absence of a written nucleus. This occurs with syllables ending in -ui (from wei: wèi → -uì) and in -iu (from you: yòu → -iù). That is, in the absence of a written nucleus the finals have priority for receiving the tone marker, as long as they are vowels: if not, the medial takes the diacritic.

An algorithm to find the correct vowel letter (when there is more than one) is as follows:[43]

- If there is an a or an e, it will take the tone mark

- If there is an ou, then the o takes the tone mark

- Otherwise, the second vowel takes the tone mark

Worded differently,

- If there is an a, e, or o, it will take the tone mark; in the case of ao, the mark goes on the a

- Otherwise, the vowels are -iu or -ui, in which case the second vowel takes the tone mark

The above can be summarized as the following table. The vowel letter taking the tone mark is indicated by the fourth-tone mark.

Placement of the tone mark in Pinyin -a -e -i -o -u a- ài ào e- èi i- ià, iào iè iò iù o- òu u- uà, uài uè uì uò ü- (üà) üè

Phonological intuition

The placement of the tone marker, when more than one of the written letters a, e, i, o, and u appears, can also be inferred from the nature of the vowel sound in the medial and final. The rule is that the tone marker goes on the spelled vowel that is not a (near-)semi-vowel. The exception is that, for triphthongs that are spelled with only two vowel letters, both of which are the semi-vowels, the tone marker goes on the second spelled vowel.

Specifically, if the spelling of a diphthong begins with i (as in ia) or u (as in ua), which serves as a near-semi-vowel, this letter does not take the tone marker. Likewise, if the spelling of a diphthong ends with o or u representing a near-semi-vowel (as in ao or ou), this letter does not receive a tone marker. In a triphthong spelled with three of a, e, i, o, and u (with i or u replaced by y or w at the start of a syllable), the first and third letters coincide with near-semi-vowels and hence do not receive the tone marker (as in iao or uai or iou). But if no letter is written to represent a triphthong's middle (non-semi-vowel) sound (as in ui or iu), then the tone marker goes on the final (second) vowel letter.

Using tone colors

In addition to tone number and mark, tone color has been suggested as a visual aid for learning. Although there are no formal standards, there are a number of different color schemes in use, Dummitt's being one of the first.

| Scheme | Tone 1 | Tone 2 | Tone 3 | Tone 4 | Neutral tone |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dummitt[44] | red | orange | green | blue | none/black |

| MDBG | red | orange | green | blue | black |

| Unimelb[lower-alpha 2] | blue | green | purple | red | grey |

| Hanping[45] | blue | green | orange | red | grey |

| Pleco | red | green | blue | purple | grey |

| Thomas[lower-alpha 2] | green | blue | red | black | grey |

- Based on the Beijing dialect of Mandarin.

- The colors used here to illustrate Unimelb and Thomas are only approximate. The precise color values used by Dummitt, the MDBG Chinese Online Dictionary, Hanping, and Pleco are taken from Laowai's blog Tone Colors and What Pleco Did with Them.

Indication of tone change in pinyin spelling

Tone sandhi (tone change) is usually not reflected in pinyin spelling — the underlying tone (i.e. the original tone before the sandhi) is still written. However, ABC English–Chinese, Chinese–English Dictionary (2010)[46] uses the following notation to indicate both the original tone and the tone after the sandhi:

- 一 (yī) pronounced in second tone (yí) is written as yị̄.[lower-alpha 1]

- e.g. 一共 (underlying yīgòng, realized as yígòng) is written as yị̄gòng

- 一 (yī) pronounced in fourth tone (yì) is written as yī̠.

- e.g. 一起 (underlying yīqǐ, realized as yìqǐ) is written as yī̠qǐ

- 不 (bù) pronounced in second tone (bú) is written as bụ̀.

- e.g. 不要 (underlying bùyào, realized as búyào) is written as bụ̀yào

- When there are two consecutive third-tone syllables, the first syllable is pronounced in second tone. A dot is added below to the third tone pronounced in second tone (i.e. written as ạ̌/Ạ̌, ẹ̌/Ẹ̌, ị̌,[lower-alpha 1] ọ̌/Ọ̌, ụ̌, and ụ̈̌).

- e.g. 了解 (underlying liǎojiě, realized as liáojiě) is written as liạ̌ojiě

Wenlin Software for learning Chinese also adopted this notation.

- Due to a bug in some fonts, a tittle (overdot) may be displayed in ị̄ and ị̌. They should be displayed without the tittle (i.e. ī or ǐ with a dot below), like they appear in the cited dictionary.

Orthographic rules

Letters

The Scheme for the Chinese Phonetic Alphabet lists the letters of pinyin, along with their pronunciations, as:

| Letter | Aa | Bb | Cc | Dd | Ee | Ff | Gg | Hh | Ii | Jj | Kk | Ll | Mm | Nn | Oo | Pp | Rr | Ss | Tt | Uu | Vv | Ww | Xx | Yy | Zz | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation (pinyin) | a | bê | cê | dê | e | êf | gê | ha | yi | jie | kê | êl | êm | nê | o | pê | qiu | ar | ês | tê | wu | vê | wa | xi | ya | zê |

| Bopomofo transcription | ㄚ | ㄅㄝ | ㄘㄝ | ㄉㄝ | ㄜ | ㄝㄈ | ㄍㄝ | ㄏㄚ | ㄧ | ㄐㄧㄝ | ㄎㄝ | ㄝㄌ | ㄝㄇ | ㄋㄝ | ㄛ | ㄆㄝ | ㄑㄧㄡ | ㄚㄦ | ㄝㄙ | ㄊㄝ | ㄨ | ㄪㄝ | ㄨㄚ | ㄒㄧ | ㄧㄚ | ㄗㄝ |

Pinyin differs from other romanizations in several aspects, such as the following:

- Syllables starting with u are written as w in place of u (e.g., *uan is written as wan). Standalone u is written as wu.

- Syllables starting with i are written as y in place of i (e.g., *ian is written as yan). Standalone i is written as yi.

- Syllables starting with ü are written as yu in place of ü (e.g., *üe is written as yue). Standalone ü is written as yu.

- ü is written as u when there is no ambiguity (such as ju, qu, and xu) but as ü when there are corresponding u syllables (such as lü and nü). If there are corresponding u syllables, it is often replaced with v on a computer to make it easier to type on a standard keyboard.

- After by a consonant, iou, uei, and uen are simplified as iu, ui, and un, which do not represent the actual pronunciation.

- As in zhuyin, syllables that are actually pronounced as buo, puo, muo, and fuo are given a separate representation: bo, po, mo, and fo.

- The apostrophe (') is used before a syllable starting with a vowel (a, o, or e) in a syllable other than the first of a word, the syllable being most commonly realized as [ɰ] unless it immediately follows a hyphen or other dash.[38] That is done to remove ambiguity that could arise, as in Xi'an, which consists of the two syllables xi (西) an (安), compared to such words as xian (先). (The ambiguity does not occur when tone marks are used since both tone marks in "Xīān" unambiguously show that the word has two syllables. However, even with tone marks, the city is usually spelled with an apostrophe as "Xī'ān".)

- Eh alone is written as ê; elsewhere as e. Schwa is always written as e.

- Zh, ch, and sh can be abbreviated as ẑ, ĉ, and ŝ (z, c, s with a circumflex). However, the shorthands are rarely used because of the difficulty of entering them on computers and are confined mainly to Esperanto keyboard layouts. Early drafts and some published material used diacritic hooks below instead: ᶎ (ȥ/ʐ), ꞔ, ʂ (ᶊ).[47]

- Ng has the uncommon shorthand of ŋ, which was also used in early drafts.

- Early drafts also contained the symbol ɥ or the letter ч borrowed from the Cyrillic script, in place of later j for the voiceless alveolo-palatal sibilant affricate.[47]

- The letter v is unused, except in spelling foreign languages, languages of minority nationalities, and some dialects, despite a conscious effort to distribute letters more evenly than in Western languages. However, the ease of typing into a computer causes the v to be sometimes used to replace ü. (The Scheme table above maps the letter to bopomofo ㄪ, which typically maps to /v/.)

Most of the above are used to avoid ambiguity when words of more than one syllable are written in pinyin. For example, uenian is written as wenyan because it is not clear which syllables make up uenian; uen-ian, uen-i-an, u-en-i-an, u-e-nian, and u-e-ni-an are all possible combinations, but wenyan is unambiguous since we, nya, etc. do not exist in pinyin. See the pinyin table article for a summary of possible pinyin syllables (not including tones).

Words, capitalization, initialisms and punctuation

Although Chinese characters represent single syllables, Mandarin Chinese is a polysyllabic language. Spacing in pinyin is usually based on words, and not on single syllables. However, there are often ambiguities in partitioning a word.

The Basic Rules of the Chinese Phonetic Alphabet Orthography (汉语拼音正词法基本规则; 漢語拼音正詞法基本規則; Hànyǔ Pīnyīn Zhèngcífǎ Jīběn Guīzé) were put into effect in 1988 by the National Educational Commission (国家教育委员会; 國家教育委員會; Guójiā Jiàoyù Wěiyuánhuì) and the National Language Commission (国家语言文字工作委员会; 國家語言文字工作委員會; Guójiā Yǔyán Wénzì Gōngzuò Wěiyuánhuì).[48] These rules became a Guóbiāo recommendation in 1996[48][49] and were updated in 2012.[50]

- General

- Single meaning: Words with a single meaning, which are usually set up of two characters (sometimes one, seldom three), are written together and not capitalized: rén (人, person); péngyou (朋友, friend); qiǎokèlì (巧克力, chocolate)

- Combined meaning (2 or 3 characters): Same goes for words combined of two words to one meaning: hǎifēng (海风; 海風, sea breeze); wèndá (问答; 問答, question and answer); quánguó (全国; 全國, nationwide); chángyòngcí (常用词; 常用詞, common words)

- Combined meaning (4 or more characters): Words with four or more characters having one meaning are split up with their original meaning if possible: wúfèng gāngguǎn (无缝钢管; 無縫鋼管, seamless steel-tube); huánjìng bǎohù guīhuà (环境保护规划; 環境保護規劃, environmental protection planning); gāoměngsuānjiǎ (高锰酸钾; 高錳酸鉀, potassium permanganate)

- Duplicated words

- AA: Duplicated characters (AA) are written together: rénrén (人人, everybody), kànkan (看看, to have a look), niánnián (年年, every year)

- ABAB: Two characters duplicated (ABAB) are written separated: yánjiū yánjiū (研究研究, to study, to research), xuěbái xuěbái (雪白雪白, white as snow)

- AABB: Characters in the AABB schema are written together: láiláiwǎngwǎng (来来往往; 來來往往, come and go), qiānqiānwànwàn (千千万万; 千千萬萬, numerous)

- Prefixes (前附成分; qiánfù chéngfèn) and Suffixes (后附成分; 後附成分; hòufù chéngfèn): Words accompanied by prefixes such as fù (副, vice), zǒng (总; 總, chief), fēi (非, non-), fǎn (反, anti-), chāo (超, ultra-), lǎo (老, old), ā (阿, used before names to indicate familiarity), kě (可, -able), wú (无; 無, -less) and bàn (半, semi-) and suffixes such as zi (子, noun suffix), r (儿; 兒, diminutive suffix), tou (头; 頭, noun suffix), xìng (性, -ness, -ity), zhě (者, -er, -ist), yuán (员; 員, person), jiā (家, -er, -ist), shǒu (手, person skilled in a field), huà (化, -ize) and men (们; 們, plural marker) are written together: fùbùzhǎng (副部长; 副部長, vice minister), chéngwùyuán (乘务员; 乘務員, conductor), háizimen (孩子们; 孩子們, children)

- Nouns and names (名词; 名詞; míngcí)

- Words of position are separated: mén wài (门外; 門外, outdoor), hé li (河里; 河裏, under the river), huǒchē shàngmian (火车上面; 火車上面, on the train), Huáng Hé yǐnán (黄河以南; 黃河以南, south of the Yellow River)

- Exceptions are words traditionally connected: tiānshang (天上, in the sky or outerspace), dìxia (地下, on the ground), kōngzhōng (空中, in the air), hǎiwài (海外, overseas)

- Surnames are separated from the given names, each capitalized: Lǐ Huá (李华; 李華), Zhāng Sān (张三; 張三). If the surname and/or given name consists of two syllables, it should be written as one: Zhūgě Kǒngmíng (诸葛孔明; 諸葛孔明).

- Titles following the name are separated and are not capitalized: Wáng bùzhǎng (王部长; 王部長, Minister Wang), Lǐ xiānsheng (李先生, Mr. Li), Tián zhǔrèn (田主任, Director Tian), Zhào tóngzhì (赵同志; 趙同志, Comrade Zhao).

- The forms of addressing people with prefixes such as Lǎo (老), Xiǎo (小), Dà (大) and Ā (阿) are capitalized: Xiǎo Liú (小刘; 小劉, [young] Ms./Mr. Liu), Dà Lǐ (大李, [great; elder] Mr. Li), Ā Sān (阿三, Ah San), Lǎo Qián (老钱; 老錢, [senior] Mr. Qian), Lǎo Wú (老吴; 老吳, [senior] Mr. Wu)

- Exceptions include Kǒngzǐ (孔子, Confucius), Bāogōng (包公, Judge Bao), Xīshī (西施, Xishi), Mèngchángjūn (孟尝君; 孟嘗君, Lord Mengchang)

- Geographical names of China: Běijīng Shì (北京市, city of Beijing), Héběi Shěng (河北省, province of Hebei), Yālù Jiāng (鸭绿江; 鴨綠江, Yalu River), Tài Shān (泰山, Mount Tai), Dòngtíng Hú (洞庭湖, Dongting Lake), Qióngzhōu Hǎixiá (琼州海峡; 瓊州海峽, Qiongzhou Strait)

- Monosyllabic prefixes and suffixes are written together with their related part: Dōngsì Shítiáo (东四十条; 東四十條, Dongsi 10th Alley)

- Common geographical nouns that have become part of proper nouns are written together: Hēilóngjiāng (黑龙江; 黑龍江, Heilongjiang)

- Non-Chinese names are written in Hanyu Pinyin: Āpèi Āwàngjìnměi (阿沛·阿旺晋美; 阿沛·阿旺晉美, Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme); Dōngjīng (东京; 東京, Tokyo)

- Words of position are separated: mén wài (门外; 門外, outdoor), hé li (河里; 河裏, under the river), huǒchē shàngmian (火车上面; 火車上面, on the train), Huáng Hé yǐnán (黄河以南; 黃河以南, south of the Yellow River)

- Verbs (动词; 動詞; dòngcí): Verbs and their suffixes -zhe (着; 著), -le (了) or -guo ((过; 過) are written as one: kànzhe (看着; 看著, seeing), jìnxíngguo (进行过; 進行過, have been implemented). Le as it appears in the end of a sentence is separated though: Huǒchē dào le. (火车到了; 火車到了, The train [has] arrived).

- Verbs and their objects are separated: kàn xìn (看信, read a letter), chī yú (吃鱼; 吃魚, eat fish), kāi wánxiào (开玩笑; 開玩笑, to be kidding).

- If verbs and their complements are each monosyllabic, they are written together; if not, they are separated: gǎohuài (搞坏; 搞壞, to make broken), dǎsǐ (打死, hit to death), huàwéi (化为; 化為, to become), zhěnglǐ hǎo (整理好, to sort out), gǎixiě wéi (改写为; 改寫為, to rewrite as)

- Adjectives (形容词; 形容詞; xíngróngcí): A monosyllabic adjective and its reduplication are written as one: mēngmēngliàng (矇矇亮, dim), liàngtángtáng (亮堂堂, shining bright)

- Complements of size or degree such as xiē (些), yīxiē (一些), diǎnr (点儿; 點兒) and yīdiǎnr (一点儿; 一點兒) are written separated: dà xiē (大些), a little bigger), kuài yīdiǎnr (快一点儿; 快一點兒, a bit faster)

- Pronouns (代词; 代詞; dàicí)

- Personal pronouns and interrogative pronouns are separated from other words: Wǒ ài Zhōngguó. (我爱中国。; 我愛中國。, I love China); Shéi shuō de? (谁说的?; 誰說的?, Who said it?)

- The demonstrative pronoun zhè (这; 這, this), nà (那, that) and the question pronoun nǎ (哪, which) are separated: zhè rén (这人; 這人, this person), nà cì huìyì (那次会议; 那次會議, that meeting), nǎ zhāng bàozhǐ (哪张报纸; 哪張報紙, which newspaper)

- Exception—If zhè, nà or nǎ are followed by diǎnr (点儿; 點兒), bān (般), biān (边; 邊), shí (时; 時), huìr (会儿; 會兒), lǐ (里; 裏), me (么; 麼) or the general classifier ge (个; 個), they are written together: nàlǐ (那里; 那裏, there), zhèbiān (这边; 這邊, over here), zhège (这个; 這個, this)

- Numerals (数词; 數詞; shùcí) and measure words (量词; 量詞; liàngcí)

- Numbers and words like gè (各, each), měi (每, each), mǒu (某, any), běn (本, this), gāi (该; 該, that), wǒ (我, my, our) and nǐ (你, your) are separated from the measure words following them: liǎng gè rén (两个人; 兩個人, two people), gè guó (各国; 各國, every nation), měi nián (每年, every year), mǒu gōngchǎng (某工厂; 某工廠, a certain factory), wǒ xiào (我校, our school)

- Numbers up to 100 are written as single words: sānshísān (三十三, thirty-three). Above that, the hundreds, thousands, etc. are written as separate words: jiǔyì qīwàn èrqiān sānbǎi wǔshíliù (九亿七万二千三百五十六; 九億七萬二千三百五十六, nine hundred million, seventy-two thousand, three hundred fifty-six). Arabic numerals are kept as Arabic numerals: 635 fēnjī (635 分机; 635 分機, extension 635)

- According to 汉语拼音正词法基本规则 6.1.5.4, the dì (第) used in ordinal numerals is followed by a hyphen: dì-yī (第一, first), dì-356 (第 356, 356th). The hyphen should not be used if the word in which dì (第) and the numeral appear does not refer to an ordinal number in the context. For example: Dìwǔ (第五, a Chinese compound surname).[51][52] The chū (初) in front of numbers one to ten is written together with the number: chūshí (初十, tenth day)

- Numbers representing month and day are hyphenated: wǔ-sì (五四, May fourth), yīèr-jiǔ (一二·九, December ninth)

- Words of approximations such as duō (多), lái (来; 來) and jǐ (几; 幾) are separated from numerals and measure words: yībǎi duō gè (一百多个; 一百多個, around a hundred); shí lái wàn gè (十来万个; 十來萬個, around a hundred thousand); jǐ jiā rén (几家人; 幾家人, a few families)

- Shíjǐ (十几; 十幾, more than ten) and jǐshí (几十; 幾十, tens) are written together: shíjǐ gè rén (十几个人; 十幾個人, more than ten people); jǐ shí gēn gāngguǎn (几十根钢管; 幾十根鋼管, tens of steel pipes)

- Approximations with numbers or units that are close together are hyphenated: sān-wǔ tiān (三五天, three to five days), qiān-bǎi cì (千百次, thousands of times)

- Other function words (虚词; 虛詞; xūcí) are separated from other words

- Adverbs (副词; 副詞; fùcí): hěn hǎo (很好, very good), zuì kuài (最快, fastest), fēicháng dà (非常大, extremely big)

- Prepositions (介词; 介詞; jiècí): zài qiánmiàn (在前面, in front)

- Conjunctions (连词; 連詞; liáncí): nǐ hé wǒ (你和我, you and I/me), Nǐ lái háishi bù lái? (你来还是不来?; 你來還是不來?, Are you coming or not?)

- "Constructive auxiliaries" (结构助词; 結構助詞; jiégòu zhùcí) such as de (的/地/得), zhī (之) and suǒ (所): mànmàn de zou (慢慢地走), go slowly)

- A monosyllabic word can also be written together with de (的/地/得): wǒ de shū / wǒde shū (我的书; 我的書, my book)

- Modal auxiliaries at the end of a sentence: Nǐ zhīdào ma? (你知道吗?; 你知道嗎?, Do you know?), Kuài qù ba! (快去吧!, Go quickly!)

- Exclamations and interjections: À! Zhēn měi! (啊!真美!), Oh, it's so beautiful!)

- Onomatopoeia: mó dāo huòhuò (磨刀霍霍, honing a knife), hōnglōng yī shēng (轰隆一声; 轟隆一聲, rumbling)

- Capitalization

- The first letter of the first word in a sentence is capitalized: Chūntiān lái le. (春天来了。; 春天來了。, Spring has arrived.)

- The first letter of each line in a poem is capitalized.

- The first letter of a proper noun is capitalized: Běijīng (北京, Beijing), Guójì Shūdiàn (国际书店; 國際書店, International Bookstore), Guójiā Yǔyán Wénzì Gōngzuò Wěiyuánhuì (国家语言文字工作委员会; 國家語言文字工作委員會, National Language Commission)

- On some occasions, proper nouns can be written in all caps: BĚIJĪNG, GUÓJÌ SHŪDIÀN, GUÓJIĀ YǓYÁN WÉNZÌ GŌNGZUÒ WĚIYUÁNHUÌ

- If a proper noun is written together with a common noun to make a proper noun, it is capitalized. If not, it is not capitalized: Fójiào (佛教, Buddhism), Tángcháo (唐朝, Tang dynasty), jīngjù (京剧; 京劇, Beijing opera), chuānxiōng (川芎, Szechuan lovage)

- Title case is used for the names of books,[53] newspapers,[54] magazines[54] and other artistic works.[53] As in English, certain function words (e.g. de, hé, zài) are not capitalized:[53] Kuángrén Rìjì (狂人日记, Diary of a Madman), Tàiyáng Zhào zài Sānggàn Hé shàng (太阳照在桑干河上, The Sun Shines over the Sanggan River ), Zhōngguó Qīngnián Bào (中国青年报 China Youth Daily).

- Initialisms

- Single words are abbreviated by taking the first letter of each character of the word: Beǐjīng (北京, Beijing) → BJ

- A group of words are abbreviated by taking the first letter of each word in the group: guójiā biāozhǔn (国家标准; 國家標準, Guóbiāo standard) → GB

- Initials can also be indicated using full stops: Beǐjīng → B.J., guójiā biāozhǔn → G.B.

- When abbreviating names, the surname is written fully (first letter capitalized or in all caps), but only the first letter of each character in the given name is taken, with full stops after each initial: Lǐ Huá (李华; 李華) → Lǐ H. or LǏ H., Zhūgě Kǒngmíng (诸葛孔明; 諸葛孔明) → Zhūgě K. M. or ZHŪGĚ K. M.

- Line wrapping

- Words can only be split by the character:

guāngmíng (光明, bright) → guāng-

míng, not gu-

āngmíng - Initials cannot be split:

Wáng J. G. (王建国; 王建國) → Wáng

J. G., not Wáng J.-

G. - Apostrophes are removed in line wrapping:

Xī'ān (西安, Xi'an) → Xī-

ān, not Xī-

'ān - When the original word has a hyphen, the hyphen is added at the beginning of the new line:

chēshuǐ-mǎlóng (车水马龙; 車水馬龍, heavy traffic: "carriage, water, horse, dragon") → chēshuǐ-

-mǎlóng

- Words can only be split by the character:

- Hyphenation: In addition to the situations mentioned above, there are four situations where hyphens are used.

- Coordinate and disjunctive compound words, where the two elements are conjoined or opposed, but retain their individual meaning: gōng-jiàn (弓箭, bow and arrow), kuài-màn (快慢, speed: "fast-slow"), shíqī-bā suì (十七八岁; 十七八歲, 17–18 years old), dǎ-mà (打骂; 打罵, beat and scold), Yīng-Hàn (英汉; 英漢, English–Chinese [dictionary]), Jīng-Jīn (京津, Beijing–Tianjin), lù-hǎi-kōngjūn (陆海空军; 陸海空軍, army-navy-airforce).

- Abbreviated compounds (略语; 略語; lüèyǔ): gōnggòng guānxì (公共关系; 公共關係, public relations) → gōng-guān (公关; 公關, PR), chángtú diànhuà (长途电话; 長途電話, long-distance calling) → cháng-huà (长话; 長話, LDC).

Exceptions are made when the abbreviated term has become established as a word in its own right, as in chūzhōng (初中) for chūjí zhōngxué (初级中学; 初級中學, junior high school). Abbreviations of proper-name compounds, however, should always be hyphenated: Běijīng Dàxué (北京大学; 北京大學, Peking University) → Běi-Dà (北大, PKU). - Four-syllable idioms: fēngpíng-làngjìng (风平浪静; 風平浪靜), calm and tranquil: "wind calm, waves down"), huījīn-rútǔ (挥金如土; 揮金如土, spend money like water: "throw gold like dirt"), zhǐ-bǐ-mò-yàn (纸笔墨砚; 紙筆墨硯, paper-brush-ink-inkstone [four coordinate words]).[55]

- Other idioms are separated according to the words that make up the idiom: bēi hēiguō (背黑锅; 背黑鍋, to be made a scapegoat: "to carry a black pot"), zhǐ xǔ zhōuguān fànghuǒ, bù xǔ bǎixìng diǎndēng (只许州官放火,不许百姓点灯; 只許州官放火,不許百姓點燈, Gods may do what cattle may not: "only the official is allowed to light the fire; the commoners are not allowed to light a lamp")

- Punctuation

- The Chinese full stop (。) is changed to a western full stop (.)

- The hyphen is a half-width hyphen (-)

- Ellipsis can be changed from 6 dots (......) to 3 dots (...)

- The enumeration comma (、) is changed to a normal comma (,)

- All other punctuation marks are the same as the ones used in normal texts

Comparison with other orthographies

Pinyin is now used by foreign students learning Chinese as a second language, as well as Bopomofo.

Pinyin assigns some Latin letters sound values which are quite different from those of most languages. This has drawn some criticism as it may lead to confusion when uninformed speakers apply either native or English assumed pronunciations to words. However, this problem is not limited only to pinyin, since many languages that use the Latin alphabet natively also assign different values to the same letters. A recent study on Chinese writing and literacy concluded, "By and large, pinyin represents the Chinese sounds better than the Wade–Giles system, and does so with fewer extra marks."[56]

As Pinyin is a phonetic writing system for modern Standard Chinese, it is not designed to replace Chinese characters for writing Literary Chinese, the standard written language prior to the early 1900s. In particular, Chinese characters retain semantic cues that help distinguish differently pronounced words in the ancient classical language that are now homophones in Mandarin. Thus, Chinese characters remain indispensable for recording and transmitting the corpus of Chinese writing from the past.

Pinyin is also not designed to transcribe Chinese language varieties other than Standard Chinese, which is based on the phonological system of Beijing Mandarin. Other romanization schemes have been devised to transcribe those other Chinese varieties, such as Jyutping for Cantonese and Pe̍h-ōe-jī for Hokkien.

Comparison charts

| IPA | a | ɔ | ɛ | ɤ | ai | ei | au | ou | an | ən | aŋ | əŋ | ʊŋ | aɹ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinyin | a | o | ê | e | ai | ei | ao | ou | an | en | ang | eng | ong | er |

| Tongyong Pinyin | e | |||||||||||||

| Wade–Giles | eh | ê/o | ên | êng | ung | êrh | ||||||||

| Bopomofo | ㄚ | ㄛ | ㄝ | ㄜ | ㄞ | ㄟ | ㄠ | ㄡ | ㄢ | ㄣ | ㄤ | ㄥ | ㄨㄥ | ㄦ |

| example | 阿 | 喔 | 誒 | 俄 | 艾 | 黑 | 凹 | 偶 | 安 | 恩 | 昂 | 冷 | 中 | 二 |

| IPA | i | je | jou | jɛn | in | iŋ | jʊŋ | u | wo | wei | wən | wəŋ | y | ɥe | ɥɛn | yn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinyin | yi | ye | you | yan | yin | ying | yong | wu | wo/o | wei | wen | weng | yu | yue | yuan | yun |

| Tongyong Pinyin | wun | wong | ||||||||||||||

| Wade–Giles | i/yi | yeh | yu | yen | yung | wên | wêng | yü | yüeh | yüan | yün | |||||

| Bopomofo | ㄧ | ㄧㄝ | ㄧㄡ | ㄧㄢ | ㄧㄣ | ㄧㄥ | ㄩㄥ | ㄨ | ㄨㄛ/ㄛ | ㄨㄟ | ㄨㄣ | ㄨㄥ | ㄩ | ㄩㄝ | ㄩㄢ | ㄩㄣ |

| example | 一 | 也 | 又 | 言 | 音 | 英 | 用 | 五 | 我 | 位 | 文 | 翁 | 玉 | 月 | 元 | 雲 |

| IPA | p | pʰ | m | fəŋ | tjou | twei | twən | tʰɤ | ny | ly | kɤɹ | kʰɤ | xɤ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinyin | b | p | m | feng | diu | dui | dun | te | nü | lü | ge | ke | he |

| Tongyong Pinyin | fong | diou | duei | nyu | lyu | ||||||||

| Wade–Giles | p | pʻ | fêng | tiu | tui | tun | tʻê | nü | lü | ko | kʻo | ho | |

| Bopomofo | ㄅ | ㄆ | ㄇ | ㄈㄥ | ㄉㄧㄡ | ㄉㄨㄟ | ㄉㄨㄣ | ㄊㄜ | ㄋㄩ | ㄌㄩ | ㄍㄜ | ㄎㄜ | ㄏㄜ |

| example | 玻 | 婆 | 末 | 封 | 丟 | 兌 | 頓 | 特 | 女 | 旅 | 歌 | 可 | 何 |

| IPA | tɕjɛn | tɕjʊŋ | tɕʰin | ɕɥɛn | ʈʂɤ | ʈʂɨ | ʈʂʰɤ | ʈʂʰɨ | ʂɤ | ʂɨ | ɻɤ | ɻɨ | tsɤ | tswo | tsɨ | tsʰɤ | tsʰɨ | sɤ | sɨ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinyin | jian | jiong | qin | xuan | zhe | zhi | che | chi | she | shi | re | ri | ze | zuo | zi | ce | ci | se | si |

| Tongyong Pinyin | jyong | cin | syuan | jhe | jhih | chih | shih | rih | zih | cih | sih | ||||||||

| Wade–Giles | chien | chiung | chʻin | shüan | chê | chih | chʻê | chʻih | shê | shih | jê | jih | tsê | tso | tzŭ | tsʻê | tzʻŭ | sê | ssŭ |

| Bopomofo | ㄐㄧㄢ | ㄐㄩㄥ | ㄑㄧㄣ | ㄒㄩㄢ | ㄓㄜ | ㄓ | ㄔㄜ | ㄔ | ㄕㄜ | ㄕ | ㄖㄜ | ㄖ | ㄗㄜ | ㄗㄨㄛ | ㄗ | ㄘㄜ | ㄘ | ㄙㄜ | ㄙ |

| example | 件 | 窘 | 秦 | 宣 | 哲 | 之 | 扯 | 赤 | 社 | 是 | 惹 | 日 | 仄 | 左 | 字 | 策 | 次 | 色 | 斯 |

| IPA | ma˥˥ | ma˧˥ | ma˨˩˦ | ma˥˩ | ma |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinyin | mā | má | mǎ | mà | ma |

| Tongyong Pinyin | ma | mȧ | |||

| Wade–Giles | ma1 | ma2 | ma3 | ma4 | ma |

| Bopomofo | ㄇㄚ | ㄇㄚˊ | ㄇㄚˇ | ㄇㄚˋ | ˙ㄇㄚ |

| example (Chinese characters) | 媽 | 麻 | 馬 | 罵 | 嗎 |

Unicode code points

Based on ISO 7098:2015, Information and Documentation: Chinese Romanization (《信息与文献——中文罗马字母拼写法》), tonal marks for pinyin should use the symbols from Combining Diacritical Marks, as opposed by the use of Spacing Modifier Letters in Bopomofo. Lowercase letters with tone marks are included in GB/T 2312 and their uppercase counterparts are included in JIS X 0212;[57] thus Unicode includes all the common accented characters from pinyin.[58]

Due to The Basic Rules of the Chinese Phonetic Alphabet Orthography, all accented letters are required to have both uppercase and lowercase characters as per their normal counterparts.

| Letter | First tone | Second tone | Third tone | Fourth tone | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combining Diacritical Marks | ̄ (U+0304) | ́ (U+0301) | ̌ (U+030C) | ̀ (U+0300) | ||||||||||||

| Common letters | ||||||||||||||||

| Uppercase | A | Ā (U+0100) | Á (U+00C1) | Ǎ (U+01CD) | À (U+00C0) | |||||||||||

| E | Ē (U+0112) | É (U+00C9) | Ě (U+011A) | È (U+00C8) | ||||||||||||

| I | Ī (U+012A) | Í (U+00CD) | Ǐ (U+01CF) | Ì (U+00CC) | ||||||||||||

| O | Ō (U+014C) | Ó (U+00D3) | Ǒ (U+01D1) | Ò (U+00D2) | ||||||||||||

| U | Ū (U+016A) | Ú (U+00DA) | Ǔ (U+01D3) | Ù (U+00D9) | ||||||||||||

| Ü (U+00DC) | Ǖ (U+01D5) | Ǘ (U+01D7) | Ǚ (U+01D9) | Ǜ (U+01DB) | ||||||||||||

| Lowercase | a | ā (U+0101) | á (U+00E1) | ǎ (U+01CE) | à (U+00E0) | |||||||||||

| e | ē (U+0113) | é (U+00E9) | ě (U+011B) | è (U+00E8) | ||||||||||||

| i | ī (U+012B) | í (U+00ED) | ǐ (U+01D0) | ì (U+00EC) | ||||||||||||

| o | ō (U+014D) | ó (U+00F3) | ǒ (U+01D2) | ò (U+00F2) | ||||||||||||

| u | ū (U+016B) | ú (U+00FA) | ǔ (U+01D4) | ù (U+00F9) | ||||||||||||

| ü (U+00FC) | ǖ (U+01D6) | ǘ (U+01D8) | ǚ (U+01DA) | ǜ (U+01DC) | ||||||||||||

| Rare letters | ||||||||||||||||

| Uppercase | Ê (U+00CA) | Ê̄ (U+00CA U+0304) | Ế (U+1EBE) | Ê̌ (U+00CA U+030C) | Ề (U+1EC0) | |||||||||||

| M | M̄ (U+004D U+0304) | Ḿ (U+1E3E) | M̌ (U+004D U+030C) | M̀ (U+004D U+0300) | ||||||||||||

| N | N̄ (U+004E U+0304) | Ń (U+0143) | Ň (U+0147) | Ǹ (U+01F8) | ||||||||||||

| Lowercase | ê (U+00EA) | ê̄ (U+00EA U+0304) | ế (U+1EBF) | ê̌ (U+00EA U+030C) | ề (U+1EC1) | |||||||||||

| m | m̄ (U+006D U+0304) | ḿ (U+1E3F) | m̌ (U+006D U+030C) | m̀ (U+006D U+0300) | ||||||||||||

| n | n̄ (U+006E U+0304) | ń (U+0144) | ň (U+0148) | ǹ (U+01F9) | ||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

GBK has mapped two characters 'ḿ' and 'ǹ' to Private Use Areas in Unicode as U+E7C7 () and U+E7C8 () respectively,[60] thus some Simplified Chinese fonts (e.g. SimSun) that adheres to GBK include both characters in the Private Use Areas, and some input methods (e.g. Sogou Pinyin) also outputs the Private Use Areas code point instead of the original character. As the superset GB 18030 changed the mappings of 'ḿ' and 'ǹ',[59] this has an caused issue where the input methods and font files use different encoding standard, and thus the input and output of both characters are mixed up.[58]

| Uppercase | Lowercase | Note | Example[1] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ĉ (U+0108) | ĉ (U+0109) | Abbreviation of ch | 长/長 can be spelled as ĉáŋ |

| Ŝ (U+015C) | ŝ (U+015D) | Abbreviation of sh | 伤/傷 can be spelled as ŝāŋ |

| Ẑ (U+1E90) | ẑ (U+1E91) | Abbreviation of zh | 张/張 can be spelled as Ẑāŋ |

| Ŋ (U+014A) | ŋ (U+014B) | Abbreviation of ng | 让/讓 can be spelled as ràŋ, 嗯 can be spelled as ŋ̀ |

Notes

| |||

Other symbols that are used in pinyin is as follow:

| Symbol in Chinese | Symbol in pinyin | Usage | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| 。(U+3002) | . (U+002E) | Marks end of sentence. | 你好。 Nǐ hǎo. |

| ,(U+FF0C)/、 (U+3001) | , (U+002C) | Marks connecting sentence. | 你,好吗? Nǐ, hǎo ma? |

| —— (U+2014 U+2014) | — (U+2014) | Indicates breaking of meaning mid-sentence. | 枢纽部分——中央大厅 shūniǔ bùfèn — zhōngyāng dàtīng |

| …… (U+2026 U+2026) | … (U+2026) | Used for omitting a word, phrase, line, paragraph, or more from a quoted passage. | 我…… Wǒ… |

| · (U+00B7) | Marks for the neutral tone, can be placed before the neutral-tone syllable. | 吗 ·ma | |

| - (U+002D) | Hyphenation between abbreviated compounds. | 公关 gōng-guān | |

| ' (U+0027) | Indicates separate syllables. | 西安 Xī'ān (compared to 先 xiān) |

Other punctuation mark and symbols in Chinese are to use the equivalent symbol in English noted in to GB/T 15834.

In educational usage, to match the handwritten style, some fonts used a different style for the letter a and g to have an appearance of single-storey a and single-storey g. Fonts that follow GB/T 2312 usually make single-storey a in the accented pinyin characters but leaving unaccented double-storey a, causing a discrepancy in the font itself.[58] Unicode did not provide an official way to encode single-storey a and single-storey g, but as IPA require the differentiation of single-storey and double-storey a and g, thus the single-storey character ɑ/ɡ in IPA should be used if the need to separate single-storey a and g arises. For daily usage there is no need to differentiate single-storey and double-storey a/g.

| Alphabet | Single-storey representation | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| a | ɑ (U+0251) | IPA /ɑ/ |

| α (U+03B1) | Greek alpha, not suggested | |

| g | ɡ (U+0261) | IPA /ɡ/ |

Usage

Pinyin superseded older romanization systems such as Wade–Giles (1859; modified 1892) and postal romanization, and replaced zhuyin as the method of Chinese phonetic instruction in mainland China. The ISO adopted pinyin as the standard romanization for modern Chinese in 1982 (ISO 7098:1982, superseded by ISO 7098:2015). The United Nations followed suit in 1986.[4][61] It has also been accepted by the government of Singapore, the United States's Library of Congress, the American Library Association, and many other international institutions.[62]

The spelling of Chinese geographical or personal names in pinyin has become the most common way to transcribe them in English. Pinyin has also become the dominant method for entering Chinese text into computers in Mainland China, in contrast to Taiwan; where Bopomofo is most commonly used.

Families outside of Taiwan who speak Mandarin as a mother tongue use pinyin to help children associate characters with spoken words which they already know. Chinese families outside of Taiwan who speak some other language as their mother tongue use the system to teach children Mandarin pronunciation when they learn vocabulary in elementary school.[63][64]

Since 1958, pinyin has been actively used in adult education as well, making it easier for formerly illiterate people to continue with self-study after a short period of pinyin literacy instruction.[65]

Pinyin has become a tool for many foreigners to learn Mandarin pronunciation, and is used to explain both the grammar and spoken Mandarin coupled with Chinese characters (汉字; 漢字; Hànzì). Books containing both Chinese characters and pinyin are often used by foreign learners of Chinese. Pinyin's role in teaching pronunciation to foreigners and children is similar in some respects to furigana-based books (with hiragana letters written above or next to kanji, directly analogous to zhuyin) in Japanese or fully vocalised texts in Arabic ("vocalised Arabic").

The tone-marking diacritics are commonly omitted in popular news stories and even in scholarly works, as well as in the traditional Mainland Chinese Braille system, which is similar to pinyin, but meant for blind readers.[66] This results in some degree of ambiguity as to which words are being represented.

Computer input systems

Simple computer systems, able to display only 7-bit ASCII text (essentially the 26 Latin letters, 10 digits, and punctuation marks), long provided a convincing argument for using unaccented pinyin instead of Chinese characters. Today, however, most computer systems are able to display characters from Chinese and many other writing systems as well, and have them entered with a Latin keyboard using an input method editor. Alternatively, some PDAs, tablet computers, and digitizing tablets allow users to input characters graphically by writing with a stylus, with concurrent online handwriting recognition.

Pinyin with accents can be entered with the use of special keyboard layouts or various character map utilities. X keyboard extension includes a "Hanyu Pinyin (altgr)" layout for AltGr-triggered dead key input of accented characters.[67]

Pinyin-based sorting

Chinese characters and words can be sorted for convenient lookup by their Pinyin expressions alphabetically,[68] for example, 汉字拼音排序法 (Pinyin sorting method of Chinese characters) is sorted into "法(fǎ)汉(hàn)排(pái)拼(pīn)序(xù)音(yīn)字(zì)", with pinyin in brackets. Pinyin expressions of similar letters are ordered by their tones in the order of "tone 1, tone 2, tone 3, tone 4 and tone 5 (light tone)", such as "妈(mā), 麻(má), 马(mǎ), 骂(mà), 吗(ma)". Characters of the same sound, i.e., same Pinyin letters and tones, are normally arranged by stroke-based sorting.

Words of multiple characters can be sorted in two different ways.[69] One is to sort character by characters, if the first characters are the same, then sort by the second character, and so on. For example, 归并(guībìng),归还(guīhuán),规划(guīhuà),鬼话(guǐhuà),桂花(guìhuā). This method is used in Xiandai Hanyu Cidian. Another method is to sort according to the pinyin letters of the whole words, followed by sorting on tones when word letters are the same. For example, 归并(guībìng),规划(guīhuà),鬼话(guǐhuà),桂花(guìhuā),归还(guīhuán). This method is used in the ABC Chinese–English Dictionary.

Pinyin-based sorting is very convenient for looking up words whose pronunciations are known, but not words whose pronunciations the looker does not know.[70]

In Taiwan

Taiwan (Republic of China) adopted Tongyong Pinyin, a modification of Hanyu Pinyin, as the official romanization system on the national level between October 2002 and January 2009, when it decided to promote Hanyu Pinyin. Tongyong Pinyin ("common phonetic"), a romanization system developed in Taiwan, was designed to romanize languages and dialects spoken on the island in addition to Mandarin Chinese. The Kuomintang (KMT) party resisted its adoption, preferring the Hanyu Pinyin system used in mainland China and in general use internationally. Romanization preferences quickly became associated with issues of national identity. Preferences split along party lines: the KMT and its affiliated parties in the pan-blue coalition supported the use of Hanyu Pinyin while the Democratic Progressive Party and its affiliated parties in the pan-green coalition favored the use of Tongyong Pinyin.

Tongyong Pinyin was made the official system in an administrative order that allowed its adoption by local governments to be voluntary. Locales in Kaohsiung, Tainan and other areas use romanizations derived from Tongyong Pinyin for some district and street names. A few localities with governments controlled by the KMT, most notably Taipei, Hsinchu, and Kinmen County, overrode the order and converted to Hanyu Pinyin before the January 1, 2009 national-level decision,[7][8] though with a slightly different capitalization convention than mainland China. Most areas of Taiwan adopted Tongyong Pinyin, consistent with the national policy. Today, many street signs in Taiwan are using Tongyong Pinyin-derived romanizations,[71][72] but some, especially in northern Taiwan, display Hanyu Pinyin-derived romanizations. It is not unusual to see spellings on street signs and buildings derived from the older Wade–Giles, MPS2 and other systems.

Attempts to make pinyin standard in Taiwan have had uneven success, with most place and proper names remaining unaffected, including all major cities. Personal names on Taiwanese passports honor the choices of Taiwanese citizens, who can choose Wade-Giles, Hakka, Hoklo, Tongyong, aboriginal, or pinyin.[73] Official pinyin use is controversial, as when pinyin use for a metro line in 2017 provoked protests, despite government responses that "The romanization used on road signs and at transportation stations is intended for foreigners... Every foreigner learning Mandarin learns Hanyu pinyin, because it is the international standard...The decision has nothing to do with the nation's self-determination or any ideologies, because the key point is to ensure that foreigners can read signs."[74]

In Singapore

Singapore implemented Hanyu Pinyin as the official romanization system for Mandarin in the public sector starting in the 1980s, in conjunction with the Speak Mandarin Campaign.[75] Hanyu Pinyin is also used as the romanization system to teach Mandarin Chinese at schools.[76] While the process of Pinyinisation has been mostly successful in government communication, placenames, and businesses established in the 1980s and onward, it continues to be unpopular in some areas, most notably for personal names and vocabulary borrowed from other varieties of Chinese already established in the local vernacular.[75] In these situations, romanization continues to be based on the Chinese language variety it originated from, especially the three largest Chinese varieties traditionally spoken in Singapore (Hokkien, Teochew, and Cantonese).

For other languages

Pinyin-like systems have been devised for other variants of Chinese. Guangdong Romanization is a set of romanizations devised by the government of Guangdong province for Cantonese, Teochew, Hakka (Moiyen dialect), and Hainanese. All of these are designed to use Latin letters in a similar way to pinyin.

In addition, in accordance to the Regulation of Phonetic Transcription in Hanyu Pinyin Letters of Place Names in Minority Nationality Languages (少数民族语地名汉语拼音字母音译转写法; 少數民族語地名漢語拼音字母音譯寫法) promulgated in 1976, place names in non-Han languages like Mongolian, Uyghur, and Tibetan are also officially transcribed using pinyin in a system adopted by the State Administration of Surveying and Mapping and Geographical Names Committee known as SASM/GNC romanization. The pinyin letters (26 Roman letters, plus ü and ê) are used to approximate the non-Han language in question as closely as possible. This results in spellings that are different from both the customary spelling of the place name, and the pinyin spelling of the name in Chinese:

| Customary | Official (pinyin for local name) | Traditional Chinese name | Simplified Chinese name | Pinyin for Chinese name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shigatse | Xigazê | 日喀則 | 日喀则 | Rìkāzé |

| Urumchi | Ürümqi | 烏魯木齊 | 乌鲁木齐 | Wūlǔmùqí |

| Lhasa | Lhasa | 拉薩 | 拉萨 | Lāsà |

| Hohhot | Hohhot | 呼和浩特 | 呼和浩特 | Hūhéhàotè |

| Golmud | Golmud | 格爾木 | 格尔木 | Gé'ěrmù |

| Qiqihar | Qiqihar | 齊齊哈爾 | 齐齐哈尔 | Qíqíhā'ěr |

Tongyong Pinyin was developed in Taiwan for use in rendering not only Mandarin Chinese, but other languages and dialects spoken on the island such as Taiwanese, Hakka, and aboriginal languages.

See also

Notes

- This was part of the Soviet program of Latinization meant to reform alphabets for languages in that country to use Latin characters.

References

- GF 3006-2001 汉语拼音方案的通用键盘表示规范. National Language Commission, PRC. ISBN 7-80126-789-3.

- The online version of the canonical Guoyu Cidian (《國語辭典》 defines this term as 'a system of symbols for notation of the sounds of words, rather than for their meanings, that is sufficient to accurately record some language'. See this entry online. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- "The Development of the Hanyu Pinyin System". 人文与社会 (in Chinese). 5 December 2006. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- Margalit Fox (14 January 2017). "Zhou Youguang, Who Made Writing Chinese as Simple as ABC, Dies at 111". The New York Times.

- "Pinyin celebrates 50th birthday". Xinhua News Agency. 11 February 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- "ISO 7098:1982 – Documentation – Romanization of Chinese". Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- Shih Hsiu-Chuan (18 September 2008). "Hanyu Pinyin to be standard system in 2009". Taipei Times. p. 2.

- "Government to improve English-friendly environment". The China Post. 18 September 2008. Archived from the original on 19 September 2008.

- Copper, John F. (2014). Historical Dictionary of Taiwan (Republic of China). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-4307-1. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- Copper, John F. (2015). Historical Dictionary of Taiwan (Republic of China. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. p. xv. ISBN 9781442243064. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

But some cities, businesses, and organizations, notably in the south of Taiwan, did not accept this, as it suggested that Taiwan is more closely tied to the PRC.

- Sin, Kiong Wong (2012). Confucianism, Chinese History and Society. World Scientific. p. 72. ISBN 978-9814374477. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- Brockey, Liam Matthew (2009). Journey to the East: The Jesuit Mission to China, 1579–1724. Harvard University Press. p. 261. ISBN 978-0674028814. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- Chan, Wing-tsit; Adler, Joseph (2013). Sources of Chinese Tradition. Columbia University Press. pp. 303, 304. ISBN 978-0231517997. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- Mair, Victor H. (2002). "Sound and Meaning in the History of Characters: Views of China's Earliest Script Reformers". In Erbaugh, Mary S. (ed.). Difficult Characters: Interdisciplinary Studies of Chinese and Japanese Writing. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University National East Asian Language Resource Center.

- Ao, Benjamin (1997). "History and Prospect of Chinese Romanization". Chinese Librarianship: An International Electronic Journal. 4.

- Norman, Jerry (1988). Chinese, Cambridge Language Surveys. Cambridge University Press. p. 261. ISBN 0521296536. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- Jensen, Lionel M.; Weston, Timothy B. (2007). China's Transformations: The Stories Beyond the Headlines. Rowman & Littlefield. p. XX. ISBN 978-0742538634.

- Chen, Ping (1999). Modern Chinese: History and Sociolinguistics. Cambridge University Press. p. 186. ISBN 0521645727. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

Latinxua Sin Wenz tones.

- John DeFrancis, The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1984), pp. 246-247.

- "Father of pinyin". China Daily. 26 March 2009. Retrieved 12 July 2009. Reprinted in part as Simon, Alan (21–27 January 2011). "Father of Pinyin". China Daily Asia Weekly. Hong Kong. Xinhua. p. 20.

- Dwyer, Colin (14 January 2017). "Obituary: Zhou Youguang, Architect Of A Bridge Between Languages, Dies At 111". NPR. National Public Radio. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- Branigan, Tania (21 February 2008). "Sound Principles". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- Hessler, Peter (8 February 2004). "Oracle Bones". The New Yorker. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- Rohsenow, John S. 1989. Fifty years of script and written language reform in the PRC: the genesis of the language law of 2001. In Zhou Minglang and Sun Hongkai, eds. Language Policy in the People's Republic of China: Theory and Practice Since 1949, p. 23

- Branigan, Tania (21 February 2008). "Sound principles". The Guardian. London.

- "《汉语拼音方案》研制历程及当代发展——兼谈普通话的推广". 《语文建设》 (7). 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- 王均 (1995). 当代中國的文字改革 [Writing System Reform in Contemporary China] (in Chinese). 当代中國出版社. ISBN 9787800922985.

- "Hanyu Pinyin system turns 50". Straits Times. 11 February 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- Wiedenhof, Jeroen (Leiden University) (2004). "Purpose and effect in the transcription of Mandarin" (PDF). Proceedings of the International Conference on Chinese Studies 2004 (漢學研究國際學術研討會論文集). National Yunlin University of Science and Technology. pp. 387–402. ISBN 9860040117. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

In the Cold War era, the use of this system outside China was typically regarded as a political statement, or a deliberate identification with the Chinese communist regime. (p390)

- Terry, Edith. How Asia Got Rich: Japan, China and the Asian Miracle. M.E. Sharpe, 2002. 632. Retrieved from Google Books on August 7, 2011. ISBN 0-7656-0356-X, 9780765603562.

- Terry, Edith. How Asia Got Rich: Japan, China and the Asian Miracle. M.E. Sharpe, 2002. 633. Retrieved from Google Books on August 7, 2011. ISBN 0-7656-0356-X, 9780765603562.

- Times due to revise its Chinese spelling, New York Times February 4 1979 page 10

- "GB/T 16159-2012" (PDF). Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- You can hear recordings of the Finals here Archived 9 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Huang, Rong. 公安部最新规定 护照上的"ü"规范成"YU". Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- Li, Zhiyan. "吕"拼音到怎么写? 公安部称应拼写成"LYU". Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- Shea, Marilyn. "Pinyin / Ting - The Chinese Experience". hua.umf.maine.edu. Archived from the original on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- "Apostrophes in Hanyu Pinyin: when and where to use them". Archived from the original on 31 July 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- 怪 北捷景安站 英譯如「金幹站」. Apple Daily (Taiwan). 23 December 2012. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

北市捷運局指出,目前有7大捷運站名英譯沒有隔音符號,常讓外國人問路鬧烏龍,如大安站「Daan」被誤唸為丹站、景安站「Jingan」變成金幹站等,捷運局擬加撇號「'」或橫線「-」,以利分辨音節。