Religion in Finland

Finland is a predominantly Christian nation where 65.2% of the Finnish population of 5.6 million are members of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland (Protestant),[1] 32.0% are unaffiliated, 1.1% are Orthodox Christians, 0.9% are other Christians and 0.8% follow other religions like Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, folk religion etc.[2] These statistics do not include, for example, asylum seekers who have not been granted a permanent residence permit.[3]

| Religion by country |

|---|

|

|

There are two national churches (as opposed to state churches): the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland (Protestant), which is the primary religion representing 65.2% of the population by the end of 2022,[2] and the Finnish Orthodox Church, to which about 1.1% of the population belongs.[4][5][2] Those who officially belong to one of the two national churches have part of their taxes turned over to their respective church (approximately 1-2% of income).[6]

There are also approximately 44,000 followers of Pentecostal Christianity,[7] and more than 12,000 Catholic Christians in Finland, along with Anglicans, and some various Independent Christian communities. Prior to its Christianisation, beginning in the 11th century, Finnish paganism was the country's primary religion.

Statistics

| Year | Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland | Finnish Orthodox Church | Other | No religious affiliation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 98.1% | 1.7% | 0.2% | 0.0% |

| 1950 | 95.0% | 1.7% | 0.5% | 2.8% |

| 1980 | 90.3% | 1.1% | 0.7% | 7.8% |

| 1990 | 87.8% | 1.1% | 0.9% | 10.2% |

| 2000 | 85.1% | 1.1% | 1.1% | 12.7% |

| 2010 | 78.3% | 1.1% | 1.4% | 19.2% |

| 2011 | 77.3% | 1.1% | 1.5% | 20.1% |

| 2012 | 76.4% | 1.1% | 1.5% | 21.0% |

| 2013 | 75.2% | 1.1% | 1.5% | 22.1% |

| 2014 | 73.8% | 1.1% | 1.6% | 23.5% |

| 2015 | 73.0% | 1.1% | 1.6% | 24.3% |

| 2016 | 72.0% | 1.1% | 1.6% | 25.3% |

| 2017 | 70.9% | 1.1% | 1.6% | 26.3% |

| 2018 | 69.8% | 1.1% | 1.7% | 27.4% |

| 2019 | 68.7% | 1.1% | 1.7% | 28.5% |

| 2020 | 67.8% | 1.1% | 1.7% | 29.4% |

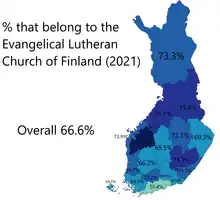

| 2021 | 66.6% | 1.1% | 1.8% | 30.6% |

| 2022 | 65.2% | 1.1% | 1.8% | 32.0% |

Most Finns are members of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland (65.2%).[8] With about 3.6 million members out of a total population of 5.6 million,[2] the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland remains one of the largest Lutheran churches in the world, though its membership is declining. In 2015, Eroakirkosta.fi, a website which offers an electronic service for resigning from Finland's national churches, reported that half a million people had resigned their membership in the church since the website was opened in 2003.[9] The number of church members leaving the Church saw a particular large increase during the fall of 2010. This was caused by statements regarding homosexuality and same-sex marriage – perceived to be intolerant towards LGBT people – made by a conservative bishop and a politician representing Christian Democrats in a TV debate on the subject.[10] The second largest group – and a rather quickly growing one – of 32.0% by the end of 2022[8] of the population is non-religious. A small minority belong to the Finnish Orthodox Church (1.1%) and to the Catholic Church (12,434 people or 0.2% of the population).[11]

Other Protestant denominations are significantly smaller, as are the Sikhs, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu and other non-Christian communities (totaling with the Catholics to about 1.8% of the population).

The main Lutheran and Orthodox churches are constitutional national churches of Finland with special roles in ceremonies and often in school morning prayers. Delegates to Lutheran Church assemblies are selected in church elections every four years.

The majority of Lutherans attend church only for special occasions like Christmas, Easter, weddings and funerals. The Lutheran Church estimates that approximately 2 percent of its members attend church services weekly. In 2004, the average number of church visits per year by church members is approximately two.[12]

According to the most recent Eurobarometer Poll (2010),[13]

- 33% of Finnish citizens "believe there is a God". (In 2005, the figure was 41%)

- 42% "believe there is some sort of spirit or life force". (In 2005, the figure was 41%)

- 22% "do not believe there is any sort of spirit, God, or life force". (In 2005, the figure was 16%)

According to Zuckerman (2005), various studies have claimed that 28% of Finns "do not believe in God" and 33 to 60% do not believe in "a personal God".[14]

Christianity

Lutheranism

In 2022, the Evangelical-Lutheran Church of Finland had about 3.6 million members, which is 65.2% of the population, registered with a parish. The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland is an episcopal church, that is governed by bishops, with a very strong tradition of parish autonomy. It comprises nine dioceses with ten bishops and 384 independent parishes.[15] The average parish has 7,000 members, with the smallest parishes comprising only a few hundred members and the largest tens of thousands.[16] In recent years many parishes have united in order to safeguard their viability. In addition, municipal mergers have prompted parochial mergers as there may be only one parish, or cluster of parishes, in a given municipality.

Orthodoxy

The Finnish Orthodox Church (Finnish: Suomen ortodoksinen kirkko; Swedish: Ortodoxa kyrkan i Finland), or Orthodox Church of Finland, is an autonomous Eastern Orthodox archdiocese of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. The Church has a legal position as a national church in the country, along with the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland. With its roots in the medieval Novgorodian missionary work in Karelia, the Finnish Orthodox Church was a part of the Russian Orthodox Church until 1923. Today the church has three dioceses and 60,000 members that account for 1.1 percent of the native population of Finland. The parish of Helsinki has the most adherents.

Catholicism

The Catholic Church in Finland is part of the worldwide Catholic Church, under the spiritual leadership of the Pope in Rome. As of 2020 there were 16,000 Catholics out of the country's population of 5.5 million.[17] There are estimated to be more than 6,000 Catholic families in the country, about half native Finns and the rest from international communities.

As of 2018 there are only five Finnish-born priests, and only three of them work in Finland. The most recent Bishop of Helsinki was Teemu Sippo, who served from 2009 to 2019. He is the first Finn to serve as a Catholic bishop in over 500 years. Currently there are more than 30 priests working in Finland from different countries. Due to the small number of Catholics in Finland, the whole country forms a single diocese, the Catholic Diocese of Helsinki. The Catholic Church in Finland is active in ecumenical matters and is a member of the Finnish Ecumenical Council, even though the worldwide Catholic Church is not a member of the World Council of Churches.

Baptist

Baptists in Finland have existed since the middle of the 19th century[18] and are part of the Baptist branch of Protestant Christianity. They were among the early free churches in Finland. There are three church associations, the Finnish Baptist Church (Finnish: Suomen Baptistikirkko), Swedish Baptist Union of Finland (Swedish: Finlands svenska baptistsamfund), and two congregations belonging to the Seventh Day Baptists. Additionally, there are several independent Baptist churches. The Baptist movement came to Finland from Sweden in the mid-1800s.[19] The Swedish Baptist Union of Finland includes 13 congregations with approximately 1000 members.[20] The Finnish Baptist Church consists of 14 congregations with about 1500 members.[21] The Seventh Day Baptist Fellowship includes two congregations with 35 members. The membership and congregation numbers of the independent Baptist churches are unknown.

Minor religions

Neopaganism

Finnish Neopaganism, or the Finnish native faith (Finnish: Suomenusko: 'Finnish Faith') is the contemporary Neopagan revival of Finnish paganism, the pre-Christian polytheistic ethnic religion of the Finns. A precursor movement was the Ukonusko ('Ukko's Faith', revolving around the god Ukko) of the early 20th century. The main problem in the revival of Finnish paganism is the nature of pre-Christian Finnish culture, which relied on oral tradition and of which very little is left. The primary sources concerning Finnish native culture are written by latter-era Christians. There are two main organisations of the religion, the Association of Finnish Native Religion (Suomalaisen kansanuskon yhdistys ry) based in Helsinki and officially registered since 2002, and the Pole Star Association (Taivaannaula ry) headquartered in Turku with branches in many cities, founded and officially registered in 2007. The Association of Finnish Native Religion also caters to Karelians and is a member of the Uralic Communion.

Buddhism

Buddhism in Finland represents a very small percentage of that nation's religious practices. In 2013 there were 5,266 followers of Buddhism in Finland, 0.1% of the population.[22] There are currently 12 Finnish cities that have Buddhist temples: in Helsinki, Hyvinkää, Hämeenlinna, Jyväskylä, Kouvola, Kuopio, Lahti, Lappeenranta, Pori, Salo, Tampere and Turku.

Bahá'í Faith

While no statistics on the numbers of Baha'is have been released, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland estimated the 2004 population of Bahá'ís to be approximately 500. Operation World, another Christian organization, estimated 0.01%, also about 500 Bahá'ís, in 2003.

In 2020 there was an estimate of 1668 Baha'í followers, according to the Association of Religion Data Archives (relying on World Christian Encyclopedia).[23]

Hinduism

Hinduism is a very minor religious faith in Finland. There are estimated to be around 5,000 Hindus in Finland, mostly from India, Nepal and Sri Lanka. Finland acquired a significant Hindu population for the first time around the turn of the 21st century due to the recruitment of information technology workers from India by companies such as Nokia.[24] In 2009, Hindu leaders in Finland protested the inclusion of a photograph that "denigrates Hinduism" in an exhibit at the Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art. The museum later removed the picture from its website.[25]

Islam

The first Muslims were Tatars who immigrated mainly between 1870 and 1920. After that there were decades with generally a small number of immigration in Finland. Since the late 20th century the number of Muslims in Finland has increased rapidly due to immigration.

According to the Finland official census (2021), there are 20,876 people in Finland belonging to registered Muslim communities, representing 0.37% of the total population.[26] However, the vast majority of Muslims in Finland do not belong to any registered communities. It is estimated that there are between 120,000 and 130,000 Muslims in Finland (2.3%).[27]

Judaism

Finnish Jews are Jews who are citizens of Finland. The country is home to approximately 1,000 Jews in 2022,[2] who mostly live in Helsinki. Jews came to Finland as traders and merchants from other parts of Europe. During the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, about 28 Finnish Jews, mostly Finnish Army veterans, fought for the State of Israel. After Israel's establishment, Finland had a high rate of immigration to Israel (known as aliyah), which depleted Finland's Jewish community. The community was somewhat revitalized when some Soviet Jews immigrated to Finland following the collapse of the Soviet Union. The number of Jews in Finland in 2010 was approximately 1,500, of whom 1,200 lived in Helsinki, about 200 in Turku, and about 50 in Tampere. Jews are well integrated into Finnish society and are represented in nearly all sectors. Most Finnish Jews are corporate employees or self-employed professionals. Most Finnish Jews speak Finnish or Swedish as their mother tongue. Yiddish, German, Russian, and Hebrew are also spoken in the community. Jews, like Finland's other traditional minorities as well as immigrant groups, are represented on the advisory board for Ethnic Relations (ETNO).There are two synagogues: one in Helsinki and one in Turku. Helsinki also has a Jewish day school, which serves about 110 students (many of them the children of Israelis working in Finland); and a Chabad Lubavitch rabbi is based there. Tampere previously had an organized Jewish community, but it stopped functioning in 1981. The other two cities continue to run their community organizations.

Population register

Traditionally, the church has played a very important role in maintaining a population register in Finland. The vicars have maintained a church record of persons born, married and deceased in their parishes since at least the 1660s, constituting one of the oldest population records in Europe. This system was in place for over 300 years. It was only replaced by a computerised central population database in 1971, while the two national churches continued to maintain population registers in co-operation with the government's local register offices until 1999, when the churches' task was limited to only maintaining a membership register.[29]

Between 1919 and 1970, a separate Civil Register was maintained of those who had no affiliation with either of the national churches.[29] Currently, the centralised Population Information System records the person's affiliation with a legally recognised religious community, if any.[30] In 2003, the new Freedom of Religion Act made it possible to resign from religious communities in writing. That is, by letter, or any written form acceptable to authorities. This is also extended to email by the 2003 electronic communications in the public sector act.[31] Resignation by email became possible in 2005 in most magistrates. Eroakirkosta.fi, an Internet campaign promoting resignation from religious communities, challenged the rest of the magistrates through a letter to the parliamentary ombudsman. In November 2006, the ombudsman recommended that all magistrates should accept resignations from religious communities via email.[32] Despite the recommendation by the ombudsman, the magistrates of Helsinki and Hämeenlinna do not accept church membership resignations sent via the Eroakirkosta.fi service.[33]

Freedom of religion

In 2023, the country was scored 4 out of 4 for religious freedom.[34]

See also

References

- "State church sees net loss of membership in 2019". 28 January 2020. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- "Belonging to a religious community by age and sex, 2000-2022". Tilastokeskuksen PX-Web tietokannat. Government. Archived from the original on 31 May 2023. Retrieved 31 May 2023. Note these are official state religious registration numbers, people may be registered yet not practicing/believing and they may be believing/practicing but not registered.

- Statistics Finland. "Statistics Finland – About statistics – Population structure". Archived from the original on 31 August 2022. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- "Kolme neljästä suomalaisesta kuuluu luterilaiseen kirkkoon". HS.fi (in Finnish). Sanoma. 1 February 2013. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- "Kirkon väestötilasto 2012". ORT.fi (in Finnish). Suomen ortodoksinen kirkko. 23 January 2012. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- "Finland". Archived from the original on 31 May 2023. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- "Helluntaiseurakuntien jäsenmäärä pienimmillään 25 vuoteen". suomenhelluntaikirkko.fi (in Finnish). Suomen helluntaikirkko. 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

- "Population". Statistics Finland. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- "Eroakirkosta.fi-palvelulla 500 000 käyttäjää – Uskontokuntiin kuulumattomien osuus kaksinkertaistunut". Archived from the original on 14 January 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- "Up to 18,000 Finns leave Lutheran Church over broadcasted anti-gay comments". Helsingin Sanomat. 18 October 2010. Archived from the original on 23 August 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- "Statistics". Catholic Diocese of Helsinki. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- "International Religious Freedom Report 2004". U.S. Department of State. 15 September 2004. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2007.

- "Special Eurobarometer Biotechnology" (PDF). Fieldwork: January–February 2010; Publication: October 2010. p. 204. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- Zuckerman, Phil (2006). "Atheism: Contemporary Numbers and Patterns". In Michael Martin (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Atheism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 47–66. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521842700.004. ISBN 978-1-139-00118-2. Archived from the original on 20 August 2023. Retrieved 19 January 2019.: 50 Some requoted at http://www.adherents.com/largecom/com_atheist.html Archived 22 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Seurakunnat". evl.fi (in Finnish). Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland. 2018. Archived from the original on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- Heino, Harri (1997). Mihin Suomi tänään uskoo [What does Finland believe in today] (in Finnish) (2nd ed.). Helsinki: WSOY. p. 44. ISBN 951-0-27265-5.

- "Finland". Catholics & Cultures. 13 October 2009. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- "Baptismen i Finland och som en världsvid trosgemenskap | Finlands Svenska Baptistsamfund". Archived from the original on 29 June 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- "Baptismen i Finland och som en världsvid trosgemenskap | Finlands Svenska Baptistsamfund". Archived from the original on 29 June 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- "Om oss | Finlands Svenska Baptistsamfund". Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- "Baptisti.fi | Suomen Baptistikirkko". www.baptisti.fi. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- "Finland Religion Facts & Stats". Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- "National Profiles | World Religion". thearda.com. Archived from the original on 14 September 2023. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- http://www.nordiclabourjournal.org/i-fokus/in-focus-2010/theme-joint-nordic-drive-for-more-foreign-labour/finlands-welfare-system-appeals-to-indian-it-engineers%7CNordic%5B%5D Labour Journal: Finland's welfare system appeals to Indian IT engineers

- Pournima, Falgun (10 March 2009). "Helsinki: Nude man photo upsetting Hindus removed from website". Hindu Janajagruti Samiti. Archived from the original on 20 January 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- "Finland: individuals in Muslim communities 2021". Statista. Archived from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- "Muslimien määrä Suomessa herättää tunteita" (in Finnish). 30 July 2022. Archived from the original on 7 August 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- "Key figures on population by region, 1990–2021". stat.fi. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- "History". VRK.fi. Population Register Centre. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- "Rekisteriselosteet". VRK.fi (in Finnish). Väestörekisterikeskus. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- "Act on Electronic Services and Communication in the Public Sector". FINLEX.fi. 16 October 2003. Archived from the original on 6 June 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- Jääskeläinen, Petri (30 November 2006). "Dnro 2051/4/05". Eduskunta.fi (in Finnish). Office of the Parliamentary Ombudsman. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- Eroakirkosta.fi – Helsingin maistraatti jarruttaa kirkosta eroamista Archived 31 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "Finland: Freedom in the World 2022 Country Report". Freedom House. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 13 September 2023.