Actinomyces

Actinomyces is a genus of the Actinomycetia class of bacteria. They all are gram-positive. Actinomyces species are facultatively anaerobic (except A. meyeri and A. israelii are obligate anaerobes), and they grow best under anaerobic conditions.[2] Actinomyces species may form endospores, and while individual bacteria are rod-shaped, Actinomyces colonies form fungus-like branched networks of hyphae.[3] The aspect of these colonies initially led to the incorrect assumption that the organism was a fungus and to the name Actinomyces, "ray fungus" (from Greek actis, ray or beam, and mykes, fungus).

| Actinomyces | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scanning electron micrograph of Actinomyces israelii | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Actinomycetota |

| Class: | Actinomycetia |

| Order: | Actinomycetales |

| Family: | Actinomycetaceae |

| Genus: | Actinomyces Harz 1877 (Approved Lists 1980)[1] |

| Species | |

|

See text. | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Actinomyces species are ubiquitous, occurring in soil and in the microbiota of animals, including the human microbiota. They are known for the important role they play in soil ecology; they produce a number of enzymes that help degrade organic plant material, lignin, and chitin. Thus, their presence is important in the formation of compost. Certain species are commensal in the skin flora, oral flora, gut flora, and vaginal flora[4] of humans and livestock. They are also known for causing diseases in humans and livestock, usually when they opportunistically gain access to the body's interior through wounds. As with other opportunistic infections, people with immunodeficiency are at higher risk. In all of the preceding traits and in their branching filament formation, they bear similarities to Nocardia.[5]

Like various other anaerobes, Actinomyces species are fastidious, thus not easy to culture and isolate. Clinical laboratories do culture and isolate them, but a negative result does not rule out infection, because it may be due simply to reluctance to grow in vitro.

Genomics

Phylogenetic trees based on 16S ribosomal RNA (16SrRNA) sequences have shown that the genus Actinomyces is quite diverse, exhibiting polyphyletic branching into several clusters. The genera Actinomyces and Mobiluncus form a monophyletic clade in a phylogenetic tree constructed using RpoB, RpoC, and DNA gyrase B protein sequences. This clade is also strongly supported by a conserved signature indel consisting of a three-amino-acid insertion in isoleucine tRNA synthetase found only in the species of the genera Actinomyces and Mobiluncus.[6]

Pathology

Actinomycota are normally present in the gums, and are the most common cause of infection in dental procedures and oral abscesses. Many Actinomyces species are opportunistic pathogens of humans and other mammals, particularly in the oral cavity.[7] In rare cases, these bacteria can cause actinomycosis, a disease characterized by the formation of abscesses in the mouth, lungs, or the gastrointestinal tract.[8] Actinomycosis is most frequently caused by A. israelii, which may also cause endocarditis, though the resulting symptoms may be similar to those resulting from infections by other bacterial species.[9][10] Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans has been identified as being of note in periodontal disease.

The genus is typically the cause of oral-cervicofacial disease. It is characterized by a painless "lumpy jaw". Lymphadenopathy is uncommon in this form of the disease. Another form of actinomycosis is thoracic disease, which is often misdiagnosed as a neoplasm, as it forms a mass that extends to the chest wall. It arises from aspiration of organisms from the oropharynx. Symptoms include chest pain, fever, and weight loss. Abdominal disease is another manifestation of actinomycosis. This can lead to a sinus tract that drains to the abdominal wall or the perianal area. Symptoms include fever, abdominal pain, and weight loss.[11] Actinomyces species have also been shown to infect the central nervous system in a dog "without history or evidence of previous trauma or other organ involvement."[12]

Pelvic actinomycosis is a rare but proven complication of use of intrauterine devices. In extreme cases, pelvic abscesses might develop. Treatment of pelvic actinomycosis associated with intrauterine devices involves removal of the device and antibiotic treatment.[13]

Diagnosis

Actinomycosis may be considered when a patient has chronic progression of disease across tissue planes that is mass-like at times, sinus tract development that may heal and recur, and refractory infection after a typical course of antibiotics.[11]

Treatment

Treatment for actinomycosis consists of antibiotics such as penicillin or amoxicillin for 5 to 12 months,[14] as well as surgery if the disease is extensive.[11]

Species

The genus Actinomyces comprises the following species:[15]

- "A. actinomycetemcomitans" Iinuma et al. 1994

- "A. bouchesdurhonensis" Fonkou et al. 2018

- A. bovis Harz 1877 (Approved Lists 1980)

- A. bowdenii Pascual et al. 1999

- "A. capricornis" Saito et al. 2021

- A. catuli Hoyles et al. 2001

- "A. culturomici" Fonkou et al. 2018

- A. dentalis Hall et al. 2005

- A. denticolens Dent and Williams 1984

- A. faecalis Zhou et al. 2021

- A. gaoshouyii Meng et al. 2017

- A. gerencseriae Johnson et al. 1990

- "A. glycerinitolerans" Palakawong Na Ayudthaya et al. 2016

- A. graevenitzii Pascual Ramos et al. 1997

- A. haliotis Hyun et al. 2014

- "A. houstonensis" Clarridge and Zhang 2002

- A. howellii Dent and Williams 1984

- "A. ihuae" Fonkou et al. 2018

- "A. ihumii" Ndongo et al. 2016

- A. israelii (Kruse 1896) Lachner-Sandoval 1898 (Approved Lists 1980)

- A. johnsonii Henssge et al. 2009

- A. lilanjuaniae Li et al. 2019

- "A. lingnae" Clarridge and Zhang 2002

- A. marmotae Yang et al. 2021

- "A. marseillensis" Fonkou et al. 2018

- A. massiliensis Renvoise et al. 2009

- "A. mediterranea" Fonkou et al. 2018

- "A. minihominis" Bilen et al. 2018

- A. naeslundii corrig. Thompson and Lovestedt 1951 (Approved Lists 1980)

- "A. oralis" Fonkou et al. 2018

- A. oricola Hall et al. 2003

- A. oris Henssge et al. 2009

- "A. pacaensis" Fonkou et al. 2018

- "A. polynesiensis" Cimmino et al. 2016

- A. procaprae Yang et al. 2021

- "A. provencensis" Ndongo et al. 2017

- A. qiguomingii Zhu et al. 2020

- A. radicidentis Collins et al. 2001

- A. respiraculi Zhou et al. 2021

- A. ruminicola An et al. 2006

- A. slackii Dent and Williams 1986

- "A. succiniciruminis" Palakawong Na Ayudthaya et al. 2016

- A. timonensis Renvoise et al. 2010

- A. trachealis Zhou et al. 2021

- "A. urinae" Morand et al. 2016

- A. urogenitalis Nikolaitchouk et al. 2000

- A. viscosus (Howell et al. 1965) Georg et al. 1969 (Approved Lists 1980)

- A. vulturis Meng et al. 2017

- A. weissii Hijazin et al. 2012

- A. wuliandei Zhu et al. 2020

Gallery

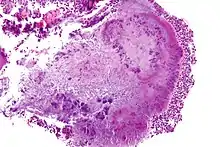

Micrograph of actinomycosis, H&E stain

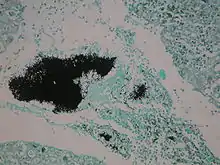

Micrograph of actinomycosis, H&E stain Micrograph of actinomycosis, GMS stain

Micrograph of actinomycosis, GMS stain Micrograph of actinomycosis, Gram stain

Micrograph of actinomycosis, Gram stain

References

- Harz CO. (1877–1878). "Actinomyces bovis, ein neuer Schimmel in den Geweben des Rindes" [Actinomyces bovis, a new mold from the tissues of cattle]. Deutsche Zeitschrift für Thiermedizin. 5: 125–140.

- Bowden, Geroge [sic] H. W. (1996), Baron, Samuel (ed.), "Actinomyces, Propionibacterium propionicus, and Streptomyces", Medical Microbiology (4th ed.), University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2, PMID 21413327, retrieved 2020-06-04

- Holt JG, ed. (1994). Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology (9th ed.). Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-683-00603-7.

- Petrova, Mariya I.; Lievens, Elke; Malik, Shweta; Imholz, Nicole; Lebeer, Sarah (2015). "Lactobacillus species as biomarkers and agents that can promote various aspects of vaginal health". Frontiers in Physiology. 6: 81. doi:10.3389/fphys.2015.00081. ISSN 1664-042X. PMC 4373506. PMID 25859220.

- Sullivan, DC; Chapman, SW (2010), "Bacteria that masquerade as fungi: actinomycosis/nocardia", Proc Am Thorac Soc, 7 (3): 216–221, doi:10.1513/pats.200907-077AL, PMID 20463251.

- Gao, B.; Gupta, R. S. (2012). "Phylogenetic Framework and Molecular Signatures for the Main Clades of the Phylum Actinobacteria". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 76 (1): 66–112. doi:10.1128/MMBR.05011-11. PMC 3294427. PMID 22390973.

- Madigan M; Martinko J, eds. (2005). Brock Biology of Microorganisms (11th ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-144329-1.

- Bowden GHW (1996). Baron S; et al. (eds.). Actinomycosis in: Baron's Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1. (via NCBI Bookshelf).

- Lam, S; Samraj, J; Rahman, S; Hilton, E (April 1993). "Primary actinomycotic endocarditis: case report and review". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 16 (4): 481–5. doi:10.1093/clind/16.4.481. PMID 8513051.

- Adalja, AA; Vergis, EN (August 2010). "Actinomyces israelii endocarditis misidentified as "Diptheroids"". Anaerobe. 16 (4): 472–3. doi:10.1016/j.anaerobe.2010.05.003. PMID 20493959.

- El Sahli, MD, MS. "Anaerobic Pathogens." Infectious Disease Module 2007. Baylor College of Medicine, 2007.

- Couto, SS; Dickinson, PJ; Jang, S; Munson, L (November 2000). "Pyogranulomatous meningoencephalitis due to Actinomyces sp. in a dog". Veterinary Pathology. 37 (6): 650–2. doi:10.1354/vp.37-6-650. PMID 11105955. S2CID 5619351.

- Joshi C, Sharma R, Mohsin Z. Pelvic actinomycosis: a rare entity presenting as tubo-ovarian abscess. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010 Feb;281(2):305-6

- "Actinomycosis: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". www.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- Euzéby JP, Parte AC. "Actinomycetaceae". List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN). Retrieved June 17, 2021.