Midwestern United States

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of the United States.[1] It was officially named the North Central Region by the Census Bureau until 1984.[2] It is between the Northeastern United States and the Western United States, with Canada to the north and the Southern United States to the south.

Midwestern United States

The Midwest, American Midwest | |

|---|---|

Region | |

.jpg.webp)      .jpg.webp) Left-right from top: Chicago, Badlands National Park, Mount Rushmore, Corn Belt, Gateway Arch, Wheat Belt, Detroit | |

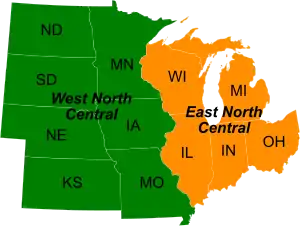

Regional definitions vary slightly among sources. This map reflects the Midwestern United States as defined by the Census Bureau, which is followed in many sources.[1] | |

| States | |

| Largest metropolitan areas |

|

| Largest cities | |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 68,985,454 |

| Demonym | Midwesterner |

The Census Bureau's definition consists of 12 states in the north central United States: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin. The region generally lies on the broad Interior Plain between the states occupying the Appalachian Mountain range and the states occupying the Rocky Mountain range. Major rivers in the region include, from east to west, the Ohio River, the Upper Mississippi River, and the Missouri River.[3] The 2020 United States census put the population of the Midwest at 68,995,685.[4] The Midwest is divided by the Census Bureau into two divisions. The East North Central Division includes Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin, all of which are also part of the Great Lakes region. The West North Central Division includes Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, North Dakota, Nebraska, and South Dakota, several of which are located, at least partly, within the Great Plains region.

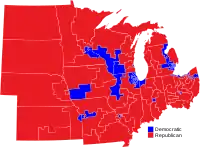

Chicago is the most populous city in the American Midwest and the third most populous in the United States. Chicago and its suburbs, together called Chicagoland, form the largest metropolitan area with 10 million people, making it the fourth largest metropolitan area in North America, after Greater Mexico City, the New York Metropolitan Area, and Greater Los Angeles. Other large Midwestern cities include (in order by population) Columbus, Indianapolis, Detroit, Milwaukee, Kansas City, Omaha, Minneapolis, Wichita, Cleveland, St. Paul, St. Louis, and Cincinnati. Large Midwestern metropolitan areas include Metro Detroit, Minneapolis–St. Paul, Greater St. Louis, Greater Cincinnati, the Kansas City metro area, the Columbus metro area, and Greater Cleveland.

Background

The term West was applied to the region in the British colonial period and in the early years of the United States. By the early 19th century, anything west of Appalachia was considered the West; over time that moniker moved to west of the Mississippi River. During the colonial period, the upper-Mississippi watershed including the Missouri and Illinois River valleys was the setting for the 17th and 18th century French settlements of the Illinois Country.[5] A region north of the Ohio River was sometime called Ohio Country.

In 1787, the Northwest Ordinance was enacted, creating the Northwest Territory, which was bounded by the Great Lakes and the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. The Northwest Territory (1787) was one of the earliest territories of the United States, stretching northwest from the Ohio River to northern Minnesota and the upper-Mississippi. Because the Northwest Territory lay between the East Coast and the then-far-West, the states carved out of it were called the Northwest. The states of the "old Northwest" are now called the "East North Central States" by the United States Census Bureau, with the "Great Lakes region" being also a popular term. The states just west of the Mississippi River and the Great Plains states are called the "West North Central States" by the Census Bureau.[6] Some entities in the Midwest have "Northwest" in their names for historical reasons, such as Northwestern University in Illinois.[7]

Another term sometimes applied to the same general region is the heartland.[8] Other designations for the region, such as the Northwest or Old Northwest and Mid-America, have fallen out of use.

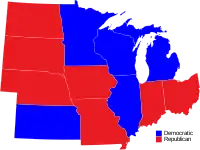

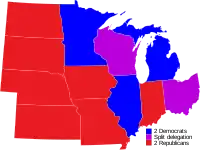

Economically the region is balanced between heavy industry and agriculture; large sections of this area make up the United States' Corn Belt, with finance and services such as medicine and education becoming increasingly important. Its central location makes it a transportation crossroads for river boats, railroads, autos, trucks, and airplanes. Politically, the region swings back and forth between the parties, and thus is heavily contested and often decisive in elections.[9][10]

After the sociological study Middletown (1929), which was based on Muncie, Indiana,[11] commentators used Midwestern cities (and the Midwest generally) as "typical" of the nation. Earlier, the rhetorical question "Will it play in Peoria?" had become a stock phrase, using Peoria, Illinois to signal whether something would appeal to mainstream America.[12] The region has a higher employment-to-population ratio (the percentage of employed people at least 16 years old) than the Northeast, the South, or the West as of 2010.[13]

Definitions

The first recorded use of the term Midwestern to refer to a region of the central U.S. occurred in 1886; Midwest appeared in 1894, and Midwesterner in 1916.[14][15] One of the earliest late-19th-century uses of Midwest was in reference to Kansas and Nebraska to indicate that they were the civilized areas of the west.[16] The term Midwestern has been in use since the 1880s to refer to portions of the central United States. A variant term, Middle West, has been used since the 19th century and remains relatively common.[17][18]

Traditional definitions of the Midwest include the Northwest Ordinance Old Northwest states and many states that were part of the Louisiana Purchase. The states of the Old Northwest are also known as Great Lakes states and are east-north central in the United States. The Ohio River runs along the southeastern section while the Mississippi River runs north to south near the center. Many of the Louisiana Purchase states in the west-north central United States are also known as the Great Plains states, where the Missouri River is a major waterway joining with the Mississippi. The Midwest lies north of the 36°30′ parallel that the 1820 Missouri Compromise established as the dividing line between future slave and non-slave states.[19]

The Midwest Region is defined by the U.S. Census Bureau as these 12 states:[1]

- Illinois: Old Northwest, Mississippi River (Missouri River joins near the state border), Ohio River, and Great Lakes state

- Indiana: Old Northwest, Ohio River, and Great Lakes state

- Iowa: Louisiana Purchase, Mississippi River, and Missouri River state

- Kansas: Louisiana Purchase, Great Plains, and Missouri River state

- Michigan: Old Northwest and Great Lakes state

- Minnesota: Old Northwest, Louisiana Purchase, Mississippi River, part of Red River Colony before 1818, Great Lakes state

- Missouri: Louisiana Purchase, Mississippi River (Ohio River joins near the state border), Missouri River, and border state

- Nebraska: Louisiana Purchase, Great Plains, and Missouri River state

- North Dakota: Louisiana Purchase, part of Red River Colony before 1818, Great Plains, and Missouri River state

- Ohio: Old Northwest (Historic Connecticut Western Reserve), Ohio River, and Great Lakes state. The southeastern part of the state is part of northern Appalachia

- South Dakota: Louisiana Purchase, Great Plains, and Missouri River state

- Wisconsin: Old Northwest, Mississippi River, and Great Lakes state

Various organizations define the Midwest with slightly different groups of states. For example, the Council of State Governments, an organization for communication and coordination among state governments, includes in its Midwest regional office eleven states from the above list, omitting Missouri, which is in the CSG South region.[20] The Midwest Region of the National Park Service consists of these twelve states plus the state of Arkansas.[21] The Midwest Archives Conference, a professional archives organization, with hundreds of archivists, curators, and information professionals as members, covers the above twelve states plus Kentucky.[22]

Physical geography

.jpg.webp)

The vast central area of the U.S., into Canada, is a landscape of low, flat to rolling terrain in the Interior Plains, ideal for farming and growing food. Most of its eastern two-thirds form the Interior Lowlands. The Lowlands gradually rise westward, from a line passing through eastern Kansas, up to over 5,000 feet (1,500 m) in the unit known as the Great Plains. Most of the Great Plains area is now farmed.[23]

While these states are for the most part relatively flat, consisting either of plains or of rolling and small hills, there is a measure of geographical variation. In particular, the following areas exhibit a high degree of topographical variety: the eastern Midwest near the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains; the Great Lakes Basin; the heavily glaciated uplands of the North Shore of Lake Superior in Minnesota, part of the ruggedly volcanic Canadian Shield; the Ozark Mountains of southern Missouri; and the deeply eroded Driftless Area of southwest Wisconsin, southeast Minnesota, northeast Iowa, and northwest Illinois.

Proceeding westward, the Appalachian Plateau topography gradually gives way to gently rolling hills and then (in central Ohio) to flat lands converted principally to farms and urban areas. This is the beginning of the vast Interior Plains of North America. As a result, prairies cover most of the Great Plains states. Iowa and much of Illinois lie within an area called the prairie peninsula, an eastward extension of prairies that borders conifer and mixed forests to the north, and hardwood deciduous forests to the east and south.

Geographers subdivide the Interior Plains into the Interior Lowlands and the Great Plains on the basis of elevation. The Lowlands are mostly below 1,500 feet (460 m) above sea level whereas the Great Plains to the west are higher, rising in Colorado to around 5,000 feet (1,500 m). The Lowlands, then, are confined to parts of Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Michigan, Tennessee, and Kentucky. Missouri and Arkansas have regions of Lowlands elevations, contrasting with their Ozark region (within the Interior Highlands). Eastern Ohio's hills are an extension of the Appalachian Plateau.

The Interior Plains are largely coincident with the vast Mississippi River Drainage System (other major components are the Missouri and Ohio Rivers). These rivers have for tens of millions of years been eroding downward into the mostly horizontal sedimentary rocks of Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic ages. The modern Mississippi River system has developed during the Pleistocene Epoch of the Cenozoic.

Rainfall decreases from east to west, resulting in different types of prairies, with the tallgrass prairie in the wetter eastern region, mixed-grass prairie in the central Great Plains, and shortgrass prairie towards the rain shadow of the Rockies. Today, these three prairie types largely correspond to the corn/soybean area, the wheat belt, and the western rangelands, respectively.

Much of the coniferous forests of the Upper Midwest were clear-cut in the late 19th century, and mixed hardwood forests have become a major component of the new woodlands since then. The majority of the Midwest can now be categorized as urbanized areas or pastoral agricultural areas.

History

Pre-Columbian

Among the American Indians Paleo-Indian cultures were the earliest in North America, with a presence in the Great Plains and Great Lakes areas from about 12,000 BCE to around 8,000 BCE.[24]

Following the Paleo-Indian period is the Archaic period (8,000 BCE to 1,000 BCE), the Woodland Tradition (1,000 BCE to 100 CE), and the Mississippian Period (900 to 1500 CE). Archaeological evidence indicates that Mississippian culture traits probably began in the St. Louis, Missouri area and spread northwest along the Mississippi and Illinois rivers and entered the state along the Kankakee River system. It also spread northward into Indiana along the Wabash, Tippecanoe, and White Rivers.[25]

Mississippian peoples in the Midwest were mostly farmers who followed the rich, flat floodplains of Midwestern rivers. They brought with them a well-developed agricultural complex based on three major crops—maize, beans, and squash. Maize, or corn, was the primary crop of Mississippian farmers. They gathered a wide variety of seeds, nuts, and berries, and fished and hunted for fowl to supplement their diets. With such an intensive form of agriculture, this culture supported large populations.[26]

The Mississippi period was characterized by a mound-building culture. The Mississippians suffered a tremendous population decline about 1400, coinciding with the global climate change of the Little Ice Age. Their culture effectively ended before 1492.[27]

Great Lakes Native Americans

The major tribes of the Great Lakes region included the Hurons, Ottawa, Chippewas or Ojibwas, Potawatomis, Winnebago (Ho-chunk), Menominees, Sacs, Neutrals, Fox, and the Miami. Most numerous were the Huron and Ho-Chunk. Fighting and battle were often launched between tribes, with the losers forced to flee.[28]

Most are of the Algonquian language family. Some tribes—such as the Stockbridge-Munsee and the Brothertown—are also Algonkian-speaking tribes who relocated from the eastern seaboard to the Great Lakes region in the 19th century. The Oneida belong to the Iroquois language group and the Ho-Chunk of Wisconsin are one of the few Great Lakes tribes to speak a Siouan language.[29] American Indians in this area did not develop a written form of language.

In the 16th century, the natives of the area used projectiles and tools of stone, bone, and wood to hunt and farm. They made canoes for fishing. Most of them lived in oval or conical wigwams that could be easily moved away. Various tribes had different ways of living. The Ojibwas were primarily hunters and fishing was also important in the Ojibwas economy. Other tribes such as Sac, Fox, and Miami, both hunted and farmed.[30]

They were oriented toward the open prairies where they engaged in communal hunts for buffalo (bison). In the northern forests, the Ottawas and Potawatomis separated into small family groups for hunting. The Winnebagos and Menominees used both hunting methods interchangeably and built up widespread trade networks extending as far west as the Rockies, north to the Great Lakes, south to the Gulf of Mexico, and east to the Atlantic Ocean.[31] The Hurons reckoned descent through the female line, while the others favored the patrilineal method. All tribes were governed under chiefdoms or complex chiefdoms. For example, Hurons were divided into matrilineal clans, each represented by a chief in the town council, where they met with a town chief on civic matters. But Chippewa people's social and political life was simpler than that of settled tribes.[32]

The religious beliefs varied among tribes. Hurons believed in Yoscaha, a supernatural being who lived in the sky and was believed to have created the world and the Huron people. At death, Hurons thought the soul left the body to live in a village in the sky. Chippewas were a deeply religious people who believed in the Great Spirit. They worshiped the Great Spirit through all their seasonal activities, and viewed religion as a private matter: Each person's relation with his personal guardian spirit was part of his thinking every day of life. Ottawa and Potawatomi people had very similar religious beliefs to those of the Chippewas.[25]

In the Ohio River Valley, the dominant food supply was not hunting but agriculture. There were orchards and fields of crops that were maintained by indigenous women. Corn was their most important crop.[33]

Great Plains Indians

The Plains Indians are the indigenous peoples who live on the plains and rolling hills of the Great Plains of North America. Their colorful equestrian culture and famous conflicts with settlers and the US Army have made the Plains Indians archetypical in literature and art for American Indians everywhere.

Plains Indians are usually divided into two broad classifications, with some degree of overlap. The first group were fully nomadic, following the vast herds of buffalo. Some tribes occasionally engaged in agriculture, growing tobacco and corn primarily. These included the Blackfoot, Arapaho, Assiniboine, Cheyenne, Comanche, Crow, Gros Ventre, Kiowa, Lakota, Lipan, Plains Apache (or Kiowa Apache), Plains Cree, Plains Ojibwe, Sarsi, Shoshone, Stoney, and Tonkawa.

The second group of Plains Indians (sometimes referred to as Prairie Indians) were the semi-sedentary tribes who, in addition to hunting buffalo, lived in villages and raised crops. These included the Arikara, Hidatsa, Iowa, Kaw (or Kansa), Kitsai, Mandan, Missouria, Nez Perce, Omaha, Osage, Otoe, Pawnee, Ponca, Quapaw, Santee, Wichita, and Yankton.[34]

The nomadic tribes of the Great Plains survived on hunting, some of their major hunts centered on deer and buffalo. Some tribes are described as part of the 'Buffalo Culture' (sometimes called, for the American Bison). Although the Plains Indians hunted other animals, such as elk or antelope, bison was their primary game food source. Bison flesh, hide, and bones from Bison hunting provided the chief source of raw materials for items that Plains Indians made, including food, cups, decorations, crafting tools, knives, and clothing.[35][36]

The tribes followed the bison's seasonal grazing and migration. The Plains Indians lived in teepees because they were easily disassembled and allowed the nomadic life of following game. When Spanish horses were obtained, the Plains tribes rapidly integrated them into their daily lives. By the early 18th century, many tribes had fully adopted a horse culture. Before their adoption of guns, the Plains Indians hunted with spears, bows, and bows and arrows, and various forms of clubs. The use of horses by the Plains Indians made hunting (and warfare) much easier.[37]

Among the most powerful and dominant tribes were the Dakota or Sioux, who occupied large amounts of territory in the Great Plains of the Midwest. The area of the Great Sioux Nation spread throughout the South and Midwest, up into the areas of Minnesota and stretching out west into the Rocky Mountains. At the same time, they occupied the heart of prime buffalo range, and also an excellent region for furs they could sell to French and American traders for goods such as guns. The Sioux (Dakota) became the most powerful of the Plains tribes and the greatest threat to American expansion.[38][39]

The Sioux comprise three major divisions based on Siouan dialect and subculture:

- Isáŋyathi or Isáŋathi ("Knife"): residing in the extreme east of the Dakotas, Minnesota and northern Iowa, and are often referred to as the Santee or Eastern Dakota.

- Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋ and Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna ("Village-at-the-end" and "little village-at-the-end"): residing in the Minnesota River area, they are considered the middle Sioux, and are often referred to as the Yankton and the Yanktonai, or, collectively, as the Wičhíyena (endonym) or the Western Dakota (and have been erroneously classified as Nakota[40]).

- Thítȟuŋwaŋ or Teton (uncertain): the westernmost Sioux, known for their hunting and warrior culture, are often referred to as the Lakota.

Today, the Sioux maintain many separate tribal governments scattered across several reservations, communities, and reserves in the Dakotas, Nebraska, Minnesota, and Montana in the United States, as well as Manitoba and southern Saskatchewan in Canada.[41]

The Middle Ground theory

The theory of the middle ground was introduced in Richard White's seminal work: The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650–1815 originally published in 1991. White defines the middle ground like so:

The middle ground is the place in between cultures, peoples, and in between empires and the non state world of villages. It is a place where many of the North American subjects and allies of empires lived. It is the area between the historical foreground of European invasion and occupation and the background of Indian defeat and retreat.

— Richard White, The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650–1815, p. XXVI

White specifically designates "the lands bordering the rivers flowing into the northern Great Lakes and the lands south of the lakes to the Ohio" as the location of the middle ground.[42] This includes the modern Midwestern states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and Michigan as well as parts of Canada.

The middle ground was formed on the foundations of mutual accommodation and common meanings established between the French and the Indians that then transformed and degraded as both were steadily lost as the French ceded their influence in the region in the aftermath of their defeat in the Seven Years' War and the Louisiana Purchase.[43]

Major aspects of the middle ground include blended culture, the fur trade, Native alliances with both the French and British, conflicts and treaties with the United States both during the Revolutionary War and after,[44][45] and its ultimate clearing/erasure throughout the nineteenth century.[46]

New France

European settlement of the area began in the 17th century following French exploration of the region and became known as New France. The French period began with the exploration of the Saint Lawrence River by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with their cessation of the majority of their holdings in North America to Great Britain in the Treaty of Paris.[47]

Marquette and Jolliet

In 1673, the Governor of New France sent Jacques Marquette, a Catholic priest and missionary, and Louis Jolliet, a fur trader, to map the way to the Northwest Passage to the Pacific. They traveled through Michigan's upper peninsula to the northern tip of Lake Michigan. On canoes, they crossed the massive lake and landed at present-day Green Bay, Wisconsin. They entered the Mississippi River on June 17, 1673.[48]

Marquette and Jolliet soon realized that the Mississippi could not possibly be the Northwest Passage because it flowed south. Nevertheless, the journey continued. They recorded much of the wildlife they encountered. They turned around at the junction of the Mississippi River and Arkansas River and headed back.

Marquette and Jolliet were the first to map the northern portion of the Mississippi River. They confirmed that it was easy to travel from the St. Lawrence River through the Great Lakes all the way to the Gulf of Mexico by water, that the native peoples who lived along the route were generally friendly, and that the natural resources of the lands in between were extraordinary. New France officials led by LaSalle followed up and erected a 4,000-mile network of fur trading posts.[49]

Fur trade

The fur trade was an integral part of early European and Indian relations. It was the foundation upon which their interactions were built and was a system that would evolve over time.

Goods often traded included guns, clothing, blankets, strouds, cloth, tobacco, silver, and alcohol.[50][51]

France

The French and Indian exchange of goods was called an exchange of gifts rather than a trade. These gifts held greater meaning to the relationship between the two than a simple economic exchange because the trade itself was inseparable from the social relations it fostered and the alliance it created.[52] In the meshed French and Algonquian system of trade, the Algonquian familial metaphor of a father and his children shaped the political relationship between the French and the Natives in this region. The French, regarded as the metaphoric father, were expected to provide for the needs of the Algonquians and, in return, the Algonquians, the metaphoric children, would be obligated to assist and obey them. Traders coming into Indian villages facilitated this system of symbolic exchange to establish or maintain alliances and friendships.[53]

Marriage also became an important aspect of the trade in both the Ohio River valley and the French pays d'en haut with the temporary closing of the French fur trade from 1690 to 1716 and beyond.[54][55] French fur traders were forced to abandon most posts and those remaining in the region became illegal traders who potentially sought these marriages to secure their safety.[54][56] Another benefit for French traders marrying Indian women was that the Indian women were in charge of the processing of the pelts necessary to the fur trade.[57] Women were integral to the fur trade and their contributions were lauded, so much so that the absence of the involvement of an Indian Woman was once cited as the cause for a trader's failure.[58] When the French fur trade re-opened in 1716 upon the discovery that their overstock of pelts had been ruined, legal French traders continued to marry Indian women and remain in their villages.[59] With the growing influence of women in the fur trade also came the increasing demand of cloth which very quickly grew to be the most desired trade good.[60]

Britain

English traders entered the Ohio country as a serious competitor to the French in the fur trade around the 1690s.[61] English (and later British) traders almost consistently offered the Indians better goods and better rates than the French, with the Indians being able to play that to their advantage, thrusting the French and the British into competition with each other to their own benefit.[61][62] The Indian demand for certain kinds of cloth in particular fueled this competition.[63] This, however, changed following the Seven Years' War with Britain's victory over France and the cession of New France to Great Britain.[64]

The British attempted to establish a more assertive relationship with the Indians of the pays d'en haut, eliminating the practise of gift giving which they now saw as unnecessary.[64] This, in combination with an underwhelming trade relationship with a surplus of whiskey, increase in prices generally, and a shortage of other goods led to unrest among the Indians that was exacerbated by the decision to significantly reduce the amount of rum being traded, a product that British merchants had been including in the trade for years. This would eventually culminate in Pontiac's War, which broke out in 1763.[65] Following the conflict, the British government was forced to compromise and loosely re-created a trade system that was an echo of the French one.[66]

American settlement

While French control ended in 1763 after their defeat in the Seven Years' War, most of the several hundred French settlers in small villages along the Mississippi River and its tributaries remained, and were not disturbed by the new British administration. By the terms of the Treaty of Paris, Spain was given Louisiana; the area west of the Mississippi. St. Louis and Ste. Genevieve in Missouri were the main towns, but there was little new settlement. France regained Louisiana from Spain in exchange for Tuscany by the terms of the Treaty of San Ildefonso in 1800. Napoleon had lost interest in re-establishing a French colonial empire in North America following the Haitian Revolution and together with the fact that France could not effectively defend Louisiana from a possible British attack, he sold the territory to the United States in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. Meanwhile, the British maintained forts and trading posts in U.S. territory, refusing to give them up until 1796 by the Jay Treaty.[67] American settlement began either via routes over the Appalachian Mountains or through the waterways of the Great Lakes. Fort Pitt (now Pittsburgh) at the source of the Ohio River became the main base for settlers moving into the Midwest. Marietta, Ohio in 1787 became the first settlement in Ohio, but not until the defeat of Native American tribes at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794 was large-scale settlement possible. Large numbers also came north from Kentucky into southern Ohio, Indiana and Illinois.[68]

The region's fertile soil produced corn and vegetables; most farmers were self-sufficient. They cut trees and claimed the land, then sold it to newcomers and then moved further west to repeat the process.[69]

Squatters

Illegal settlers, called squatters, had been encroaching on the lands now the Midwest for years before the founding of the United States of America, pushing further and further down the Ohio River during the 1760s and 1770s and inciting conflict and competition with the Native Americans whose lands they intruded on every step of the way.[70][71] These squatters were characterized by British General, Thomas Gage, as "too Numerous, too Lawless, and Licentious ever to be restrained," and regarded them as "almost out of Reach of Law and government; Neither the Endeavors of Government, or Fear of Indians has kept them properly within Bounds."[72] The British had a long-standing goal of establishing a Native American buffer state in the American Midwest to resist American westward expansion.[73][74]

When the American Revolution concluded and the formation of the United States of America began, the American government sought to evict these illegal settlers from areas that were now federally owned public lands.[70] In 1785, soldiers led by General Josiah Harmar were sent into the Ohio country to destroy the crops and burn down the homes of any squatters they found living there.[70] Eventually, after the formation of the Constitutional United States, the president became authorized to use military force to attack squatters and drive them off the land through the 1810s.[75] Squatters began to petition Congress to stop attacking them and to recognize them as actual settlers using a variety of different arguments over the first half of the nineteenth century with varying degrees of success.[76]

Congress’ regarded "actual settlers" as those who gained title to land, settled on it, and then improved upon it by building a house, clearing the ground, and planting crops – the key point being that they had first gained the title to that land.[75] Richard Young, a senator from Illinois and supporter of squatters, sought to expand the definition of an actual settler to include those who were not farmers (e.g. doctors, blacksmiths, and merchants) and proposed that they also be allowed to cheaply obtain land from the government.[77]

A number of means facilitated the legal settlement of the territories in the Midwest: land speculation, federal public land auctions, bounty land grants in lieu of pay to military veterans, and, later, preemption rights for squatters.[78] Ultimately, as they shed the image of "lawless banditti" and fashioned themselves into pioneers, squatters were increasingly able to purchase the lands on which they had settled for the minimum price thanks to various preemption acts and laws passed throughout the 1810s-1840s.[78]

Native American wars

In 1791, General Arthur St. Clair became commander of the United States Army and led a punitive expedition with two Regular Army regiments and some militia. Near modern-day Fort Recovery, his force advanced to the location of Native American settlements near the headwaters of the Wabash River, but on November 4 they were routed in battle by a tribal confederation led by Miami Chief Little Turtle and Shawnee chief Blue Jacket. More than 600 soldiers and scores of women and children were killed in the battle, which has since borne the name "St. Clair's Defeat". It remains the greatest defeat of a U.S. Army by Native Americans.[79][80][81]

The British demanded the establishment of a Native American barrier state at the Treaty of Ghent which ended the War of 1812, but American negotiators rejected the idea because Britain had lost control of the region in the Battle of Lake Erie and the Battle of the Thames in 1813, where Tecumseh was killed by U.S. forces. The British then abandoned their Native American allies south of the lakes. The Native Americans ended being the main losers in the War of 1812. Apart from the short Black Hawk War of 1832, the days of Native American warfare east of the Mississippi River had ended.[82]

Lewis and Clark

In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson commissioned the Lewis and Clark Expedition that took place between May 1804 and September 1806. Launching from Camp Dubois in Illinois, the goal was to explore the Louisiana Purchase, and establish trade and U.S. sovereignty over the native peoples along the Missouri River. The Lewis and Clark Expedition established relations with more than two dozen indigenous nations west of the Missouri River.[83] The Expedition returned east to St. Louis in the spring of 1806.

Yankees and ethnocultural politics

Yankee settlers from New England started arriving in Ohio before 1800, and spread throughout the northern half of the Midwest. Most of them started as farmers, but later the larger proportion moved to towns and cities as entrepreneurs, businessmen, and urban professionals. Since its beginnings in the 1830s, Chicago has grown to dominate the Midwestern metropolis landscape for over a century.[84]

Historian John Bunker has examined the worldview of the Yankee settlers in the Midwest:

Because they arrived first and had a strong sense of community and mission, Yankees were able to transplant New England institutions, values, and mores, altered only by the conditions of frontier life. They established a public culture that emphasized the work ethic, the sanctity of private property, individual responsibility, faith in residential and social mobility, practicality, piety, public order and decorum, reverence for public education, activists, honest, and frugal government, town meeting democracy, and he believed that there was a public interest that transcends particular and stick ambitions. Regarding themselves as the elect and just in a world rife with sin, air, and corruption, they felt a strong moral obligation to define and enforce standards of community and personal behavior....This pietistic worldview was substantially shared by British, Scandinavian, Swiss, English-Canadian and Dutch Reformed immigrants, as well as by German Protestants and many of the Forty-Eighters.[85]

Midwestern politics pitted Yankees against the German Catholics and Lutherans, who were often led by the Irish Catholics. These large groups, Buenker argues:

Generally subscribed to the work ethic, a strong sense of community, and activist government, but were less committed to economic individualism and privatism and ferociously opposed to government supervision of the personal habits. Southern and eastern European immigrants generally leaned more toward the Germanic view of things, while modernization, industrialization, and urbanization modified nearly everyone's sense of individual economic responsibility and put a premium on organization, political involvement, and education.[86][87]

Waterways

Three waterways have been important to the development of the Midwest. The first and foremost was the Ohio River, which flowed into the Mississippi River. Development of the region was halted until 1795 by Spain's control of the southern part of the Mississippi and its refusal to allow the shipment of American crops down the river and into the Atlantic Ocean.[88] This was changed with the 1795 signing of Pinckney's Treaty.[88]

The second waterway is the network of routes within the Great Lakes. The opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 completed an all-water shipping route, more direct than the Mississippi, to New York and the seaport of New York City. In 1848, The Illinois and Michigan Canal breached the continental divide spanning the Chicago Portage and linking the waters of the Great Lakes with those of the Mississippi Valley and the Gulf of Mexico. Lakeport and river cities grew up to handle these new shipping routes. During the Industrial Revolution, the lakes became a conduit for iron ore from the Mesabi Range of Minnesota to steel mills in the Mid-Atlantic States. The Saint Lawrence Seaway, completed in 1959, opened the Midwest to the Atlantic Ocean.[89]

The third waterway, the Missouri River, extended water travel from the Mississippi almost to the Rocky Mountains.

In the 1870s and 1880s, the Mississippi River inspired two classic books—Life on the Mississippi and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn—written by native Missourian Samuel Clemens, who used the pseudonym Mark Twain. His stories became staples of Midwestern lore. Twain's hometown of Hannibal, Missouri, is a tourist attraction offering a glimpse into the Midwest of his time.

Inland canals in Ohio and Indiana constituted another important waterway, which connected with Great Lakes and Ohio River traffic. The commodities that the Midwest funneled into the Erie Canal down the Ohio River contributed to the wealth of New York City, which overtook Boston and Philadelphia.[90]

Railroads and the automobile

During the mid-19th century, the region got its first railroads, and the railroad junction in Chicago became the world's largest. During the century, Chicago became the nation's railroad center. By 1910, over 20 railroads operated passenger service out of six different downtown terminals. Even today, a century after Henry Ford, six Class I railroads (Union Pacific, BNSF, Norfolk Southern, CSX, Canadian National, and Canadian Pacific) meet in Chicago.[91][92]

In the period from 1890 to 1930, many Midwestern cities were connected by electric interurban railroads, similar to streetcars. The Midwest had more interurbans than any other region. In 1916, Ohio led all states with 2,798 miles (4,503 km), Indiana followed with 1,825 miles (2,937 km). These two states alone had almost a third of the country's interurban trackage.[93] The nation's largest interurban junction was in Indianapolis. During the 1900s (decade), the city's 38 percent growth in population was attributed largely to the interurban.[94]

Competition with automobiles and buses undermined the interurban and other railroad passenger business. By 1900, Detroit was the world center of the auto industry, and soon practically every city within 200 miles was producing auto parts that fed into its giant factories.[95]

In 1903, Henry Ford founded the Ford Motor Company. Ford's manufacturing—and those of automotive pioneers William C. Durant, the Dodge brothers, Packard, and Walter Chrysler—established Detroit's status in the early 20th century as the world's automotive capital. The proliferation of businesses created a synergy that also encouraged truck manufacturers such as Rapid and Grabowsky.[96]

The growth of the auto industry was reflected by changes in businesses throughout the Midwest and nation, with the development of garages to service vehicles and gas stations, as well as factories for parts and tires. Today, greater Detroit remains home to General Motors, Chrysler, and the Ford Motor Company.[97]

American Civil War

Slavery prohibition and the Underground Railroad

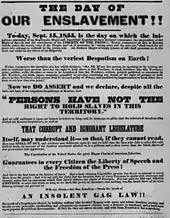

The Northwest Ordinance region, comprising the heart of the Midwest, was the first large region of the United States that prohibited slavery (the Northeastern United States emancipated slaves in the 1830s). The regional southern boundary was the Ohio River, the border of freedom and slavery in American history and literature (see Uncle Tom's Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe and Beloved by Toni Morrison).

The Midwest, particularly Ohio, provided the primary routes for the Underground Railroad, whereby Midwesterners assisted slaves to freedom from their crossing of the Ohio River through their departure on Lake Erie to Canada. Created in the early 19th century, the Underground Railroad was at its height between 1850 and 1860. One estimate suggests that by 1850, 100,000 slaves had escaped via the Underground Railroad.[98]

The Underground Railroad consisted of meeting points, secret routes, transportation, and safe houses and assistance provided by abolitionist sympathizers. Individuals were often organized in small, independent groups; this helped to maintain secrecy because individuals knew some connecting "stations" along the route, but knew few details of their immediate area. Escaped slaves would move north along the route from one way station to the next. Although the fugitives sometimes traveled on boat or train, they usually traveled on foot or by wagon.[99]

The region was shaped by the relative absence of slavery (except for Missouri), pioneer settlement, education in one-room free public schools, democratic notions brought by American Revolutionary War veterans, Protestant faiths and experimentation, and agricultural wealth transported on the Ohio River riverboats, flatboats, canal boats, and railroads.

Bleeding Kansas

The first violent conflicts leading up to the Civil War occurred between two neighboring Midwestern states, Kansas and Missouri, involving anti-slavery Free-Staters and pro-slavery "Border Ruffian" elements, that took place in the Kansas Territory and the western frontier towns of Missouri roughly between 1854 and 1858. At the heart of the conflict was the question of whether Kansas would enter the Union as a free state or slave state. As such, Bleeding Kansas was a proxy war between Northerners and Southerners over the issue of slavery. The term "Bleeding Kansas" was coined by Horace Greeley of the New-York Tribune; the events it encompasses directly presaged the Civil War.

Setting in motion the events later known as "Bleeding Kansas" was the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854. The Act created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska, opened new lands that would help settlement in them, repealed the Missouri Compromise, and allowed settlers in those territories to determine through popular sovereignty whether to allow slavery within their boundaries. It was hoped the Act would ease relations between the North and the South, because the South could expand slavery to new territories, but the North still had the right to abolish slavery in its states. Instead, opponents denounced the law as a concession to the slave power of the South.

The new Republican Party, born in the Midwest (Ripon, Wisconsin, 1854) and created in opposition to the Act, aimed to stop the expansion of slavery, and soon emerged as the dominant force throughout the North.[100]

An ostensibly democratic idea, popular sovereignty stated that the inhabitants of each territory or state should decide whether it would be a free or slave state; however, this resulted in immigration en masse to Kansas by activists from both sides. At one point, Kansas had two separate governments, each with its own constitution, although only one was federally recognized. On January 29, 1861, Kansas was admitted to the Union as a free state, less than three months before the Battle of Fort Sumter officially began the Civil War.[101]

The calm in Kansas was shattered in May 1856 by two events that are often regarded as the opening shots of the Civil War. On May 21, the Free Soil town of Lawrence, Kansas, was sacked by an armed pro‐slavery force from Missouri. A few days later, the Sacking of Lawrence led abolitionist John Brown and six of his followers to execute five men along the Pottawatomie Creek in Franklin County, Kansas, in retaliation.[102]

The so-called "Border War" lasted for another four months, from May through October, between armed bands of pro‐slavery and Free Soil men. The U.S. Army had two garrisons in Kansas, the First Cavalry Regiment at Fort Leavenworth and the Second Dragoons and Sixth Infantry at Fort Riley.[103] The skirmishes endured until a new governor, John W. Geary, managed to prevail upon the Missourians to return home in late 1856. A fragile peace followed, but violent outbreaks continued intermittently for several more years.

National reaction to the events in Kansas demonstrated how deeply divided the country had become. The Border Ruffians were widely applauded in the South, even though their actions had cost the lives of numerous people. In the North, the murders committed by Brown and his followers were ignored by most, and lauded by a few.[104]

The civil conflict in Kansas was a product of the political fight over slavery. Federal troops were not used to decide a political question, but they were used by successive territorial governors to pacify the territory so that the political question of slavery in Kansas could finally be decided by peaceful, legal, and political means.

The election of Abraham Lincoln in November 1860 was the final trigger for secession by the Southern states.[105] Efforts at compromise, including the Corwin Amendment and the Crittenden Compromise, failed. Southern leaders feared that Lincoln would stop the expansion of slavery and put it on a course toward extinction.

The U.S. federal government was supported by 20 mostly-Northern free states in which slavery already had been abolished, and by five slave states that became known as the border states. All of the Midwestern states but one, Missouri, banned slavery. Though most battles were fought in the South, skirmishes between Kansas and Missouri continued until culmination with the Lawrence Massacre on August 21, 1863. Also known as Quantrill's Raid, the massacre was a rebel guerrilla attack by Quantrill's Raiders, led by William Clarke Quantrill, on pro-Union Lawrence, Kansas. Quantrill's band of 448 Missouri guerrillas raided and plundered Lawrence, killing more than 150 and burning all the business buildings and most of the dwellings. Pursued by federal troops, the band escaped to Missouri.[106]

Lawrence was targeted because of the town's long-time support of abolition and its reputation as a center for Redlegs and Jayhawkers, which were free-state militia and vigilante groups known for attacking and families in Missouri's pro-slavery western counties.

Immigration and industrialization

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

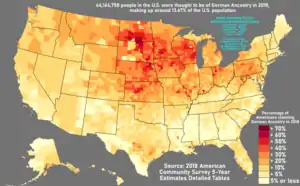

By the time of the American Civil War, European immigrants bypassed the East Coast of the United States to settle directly in the interior: German immigrants to Ohio, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Kansas, and Missouri; Irish immigrants to port cities on the Great Lakes, like Cleveland and Chicago; Danes, Czechs, Swedes, and Norwegians to Iowa, Nebraska, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and the Dakotas; and Finns to Upper Michigan and northern/central Minnesota and Wisconsin. Poles, Hungarians, and Jews settled in Midwestern cities.

The U.S. was predominantly rural at the time of the Civil War. The Midwest was no exception, dotted with small farms all across the region. The late 19th century saw industrialization, immigration, and urbanization that fed the Industrial Revolution, and the heart of industrial domination and innovation was in the Great Lakes states of the Midwest, which only began its slow decline by the late 20th century.

A flourishing economy brought residents from rural communities and immigrants from abroad. Manufacturing and retail and finance sectors became dominant, influencing the American economy.[107]

In addition to manufacturing, printing, publishing, and food processing also play major roles in the Midwest's largest economy. Chicago was the base of commercial operations for industrialists John Crerar, John Whitfield Bunn, Richard Teller Crane, Marshall Field, John Farwell, Julius Rosenwald, and many other commercial visionaries who laid the foundation for Midwestern and global industry. Meanwhile, John D. Rockefeller, creator of the Standard Oil Company, made his billions in Cleveland. At one point during the late 19th century, Cleveland was home to more than 50% of the world's millionaires, many living on the famous Millionaire's Row on Euclid Avenue.

In the 20th century, African American migration from the Southern United States into the Midwestern states changed Chicago, St. Louis, Cleveland, Milwaukee, Kansas City, Cincinnati, Detroit, Omaha, Minneapolis, and many other cities in the Midwest, as factories and schools enticed families by the thousands to new opportunities. Chicago alone gained hundreds of thousands of black citizens from the Great Migration and the Second Great Migration.

The Gateway Arch monument in St. Louis, clad in stainless steel and built in the form of a flattened catenary arch,[108] is the tallest man-made monument in the United States,[109] and the world's tallest arch.[109] Built as a monument to the westward expansion of the United States,[108] it is the centerpiece of the Gateway Arch National Park, which was known as the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial until 2018, and has become an internationally famous symbol of St. Louis and the Midwest.

German Americans

| German Immigration to the United States (by decade 1820–2004) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Decade | Number of Immigrants | Decade | Number of Immigrants |

| 1820–1840 | 160,335 | 1921–1930 | 412,202 |

| 1841–1850 | 434,626 | 1931–1940 | 114,058 |

| 1851–1860 | 951,667 | 1941–1950 | 226,578 |

| 1861–1870 | 787,468 | 1951–1960 | 477,765 |

| 1871–1880 | 718,182 | 1961–1970 | 190,796 |

| 1881–1890 | 1,452,970 | 1971–1980 | 74,414 |

| 1891–1900 | 505,152 | 1981–1990 | 91,961 |

| 1901–1910 | 341,498 | 1991–2000 | 92,606 |

| 1911–1920 | 143,945 | 2001–2004 | 61,253 |

| Total: 7,237,594 | |||

As the Midwest opened up to settlement via waterways and rail in the mid-1800s, Germans began to settle there in large numbers. The largest flow of German immigration to America occurred between 1820 and World War I, during which time nearly six million Germans immigrated to the United States. From 1840 to 1880, they were the largest group of immigrants.

The Midwestern cities of Milwaukee, Cincinnati, St. Louis, and Chicago were favored destinations of German immigrants. By 1900, the populations of the cities of Cleveland, Milwaukee, Hoboken, and Cincinnati were all more than 40 percent German American. Dubuque and Davenport, Iowa, had even larger proportions; in Omaha, Nebraska, the proportion of German Americans was 57 percent in 1910. In many other cities of the Midwest, such as Fort Wayne, Indiana, German Americans were at least 30 percent of the population.[110][111] Many concentrations acquired distinctive names suggesting their heritage, such as the "Over-the-Rhine" district in Cincinnati and "German Village" in Columbus, Ohio.[112]

A favorite destination was Milwaukee, known as "the German Athens". Radical Germans trained in politics in the old country dominated the city's Socialists. Skilled workers dominated many crafts, while entrepreneurs created the brewing industry; the most famous brands included Pabst, Schlitz, Miller, and Blatz.[113]

While half of German immigrants settled in cities, the other half established farms in the Midwest. From Ohio to the Plains states, a heavy presence persists in rural areas into the 21st century.[114][115][116]

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, German Americans showed a high interest in becoming farmers, and keeping their children and grandchildren on the land. Western railroads, with large land grants available to attract farmers, set up agencies in Hamburg and other German cities, promising cheap transportation, and sales of farmland on easy terms. For example, the Santa Fe Railroad hired its own commissioner for immigration, and sold over 300,000 acres (1,200 km2) to German-speaking farmers.[117]

Economy

Farming and agriculture

Agriculture is one of the biggest drivers of local economies in the Midwest, accounting for billions of dollars worth of exports and thousands of jobs. The area consists of some of the richest farming land in the world.[118] The region's fertile soil combined with the steel plow has made it possible for farmers to produce abundant harvests of grain and cereal crops, including corn, wheat, soybeans, oats, and barley, to become known today as the nation's "breadbasket".[119] Former Vice President Henry A. Wallace, a pioneer of hybrid seeds, declared in 1956 that the Corn Belt developed the "most productive agricultural civilization the world has ever seen".[120] Today, the U.S. produces 40 percent of the world crop.[121]

The very dense soil of the Midwest plagued the first settlers who were using wooden plows, which were more suitable for loose forest soil. On the prairie, the plows bounced around and the soil stuck to them. This problem was solved in 1837 by an Illinois blacksmith named John Deere who developed a steel moldboard plow that was stronger and cut the roots, making the fertile soils of the prairie ready for farming. Farms spread from the colonies westward along with the settlers. In cooler regions, wheat was often the crop of choice when lands were newly settled, leading to a "wheat frontier" that moved westward over the course of years. Also very common in the antebellum Midwest was farming corn while raising hogs, complementing each other especially since it was difficult to get grain to market before the canals and railroads. After the "wheat frontier" had passed through an area, more diversified farms including dairy and beef cattle generally took its place. The introduction and broad adoption of scientific agriculture since the mid-19th century contributed to economic growth in the United States.

This development was facilitated by the Morrill Act and the Hatch Act of 1887 which established in each state a land-grant university (with a mission to teach and study agriculture) and a federally funded system of agricultural experiment stations and cooperative extension networks which place extension agents in each state. Iowa State University became the nation's first designated land-grant institution when the Iowa Legislature accepted the provisions of the 1862 Morrill Act on September 11, 1862, making Iowa the first state in the nation to do so.[122] Soybeans were not widely cultivated in the United States until the early 1930s, and by 1942, the U.S. became the world's largest soybean producer, partially because of World War II and the "need for domestic sources of fats, oils, and meal". Between 1930 and 1942, the United States' share of world soybean production skyrocketed from 3 percent to 46.5 percent, largely as a result of increase in the Midwest, and by 1969, it had risen to 76 percent.[123] Iowa and Illinois rank first and second in the nation in soybean production. In 2012, Iowa produced 14.5 percent, and Illinois produced 13.3 percent of the nation's soybeans.[124]

The tallgrass prairie has been converted into one of the most intensive crop producing areas in North America. Less than one tenth of one percent (<0.09%) of the original landcover of the tallgrass prairie biome remains.[125] States formerly with landcover in native tallgrass prairie such as Iowa, Illinois, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Nebraska, and Missouri have become valued for their highly productive soils.

The Corn Belt is a region of the Midwest where corn has, since the 1850s, been the predominant crop, replacing the native tall grasses. The "Corn Belt" region is defined typically to include Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, southern Michigan, western Ohio, eastern Nebraska, eastern Kansas, southern Minnesota, and parts of Missouri.[126] As of 2008, the top four corn-producing states were Iowa, Illinois, Nebraska, and Minnesota, together accounting for more than half of the corn grown in the United States.[127] The Corn Belt also sometimes is defined to include parts of South Dakota, North Dakota, Wisconsin, and Kentucky.[128] The region is characterized by relatively level land and deep, fertile soils, high in organic matter.[129]

Iowa produces the largest corn crop of any state. In 2012, Iowa farmers produced 18.3 percent of the nation's corn, while Illinois produced 15.3 percent.[124] In 2011, there were 13.7 million harvested acres of corn for grain, producing 2.36 billion bushels, which yielded 172.0 bu/acre, with US$14.5 billion of corn value of production.[130]

Wheat is produced throughout the Midwest and is the principal cereal grain in the country. The U.S. is ranked third in production volume of wheat, with almost 58 million tons produced in the 2012–2013 growing season, behind only China and India (the combined production of all European Union nations is larger than China)[131] The U.S. ranks first in crop export volume; almost 50 percent of total wheat produced is exported. The U.S. Department of Agriculture defines eight official classes of wheat: durum wheat, hard red spring wheat, hard red winter wheat, soft red winter wheat, hard white wheat, soft white wheat, unclassed wheat, and mixed wheat.[132] Winter wheat accounts for 70 to 80 percent of total production in the U.S., with the largest amounts produced in Kansas (10.8 million tons) and North Dakota (9.8 million tons). Of the total wheat produced in the country, 50 percent is exported, valued at US$9 billion.[133]

Midwestern states also lead the nation in other agricultural commodities, including pork (Iowa), beef and veal (Nebraska), dairy (Wisconsin), and chicken eggs (Iowa).[124]

Financial

Chicago is the largest economic and financial center of the Midwest, and has the third largest gross metropolitan product in North America—approximately $689 billion, after the regions of New York City and Los Angeles. Chicago was named the fourth most important business center in the world in the MasterCard Worldwide Centers of Commerce Index.[134] The 2021 Global Financial Centres Index ranked Chicago as the fourth most competitive city in the country and eleventh in the world, directly behind Paris and Tokyo. The Chicago Board of Trade (established 1848) listed the first ever standardized "exchange traded" forward contracts, which were called futures contracts.[135] As a world financial center, Chicago is home to major financial and futures exchanges including the CME Group which owns the Chicago Mercantile Exchange ("the Merc"), Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT), the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX), the Dow Jones Indexes, and the Commodities Exchange Inc. (COMEX).[136] Other major exchanges include the Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE), the largest options exchange in the Western Hemisphere; and the Chicago Stock Exchange. In addition, Chicago is also home to the headquarters of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago (the Seventh District of the Federal Reserve).

Outside of Chicago, many other Midwest cities are host to financial centers as well. Federal Reserve Bank districts are also headquartered in Cleveland, Kansas City, Minneapolis, and St. Louis. Major United States bank headquarters are located throughout Ohio including Huntington Bancshares in Columbus, Fifth Third Bank in Cincinnati, and KeyCorp in Cleveland. Insurance Companies such as Anthem in Indianapolis, Nationwide Insurance in Columbus, American Family Insurance in Madison, Wisconsin, Berkshire Hathaway in Omaha, State Farm Insurance in Bloomington, Illinois, Reinsurance Group of America in Chesterfield, Missouri, Cincinnati Financial Corporation and American Modern Insurance Group of Cincinnati, and Progressive Insurance and Medical Mutual of Ohio in Cleveland also spread throughout the Midwest.

Manufacturing

Navigable terrain, waterways, and ports spurred an unprecedented construction of transportation infrastructure throughout the region. The region is a global leader in advanced manufacturing and research and development, with significant innovations in both production processes and business organization. John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil set precedents for centralized pricing, uniform distribution, and controlled product standards through Standard Oil, which started as a consolidated refinery in Cleveland. Cyrus McCormick's Reaper and other manufacturers of agricultural machinery consolidated into International Harvester in Chicago. Andrew Carnegie's steel production integrated large-scale open-hearth and Bessemer processes into the world's most efficient and profitable mills. The largest, most comprehensive monopoly in the world, United States Steel, consolidated steel production throughout the region. Many of the world's largest employers began in the Great Lakes region.

Advantages of accessible waterways, highly developed transportation infrastructure, finance, and a prosperous market base makes the region the global leader in automobile production and a global business location. Henry Ford's movable assembly line and integrated production set the model and standard for major car manufactures. The Detroit area emerged as the world's automotive center, with facilities throughout the region. Akron, Ohio became the global leader in rubber production, driven by the demand for tires. Over 200 million tons of cargo are shipped annually through the Great Lakes.[137][138][139]

Culture

Religion

Like the rest of the United States, the Midwest is predominantly Christian.[140]

The majority of Midwesterners are Protestants, with rates from 48 percent in Illinois to 63 percent in Iowa.[141] However, the Catholic Church is the single largest denomination, varying between 18 percent and 34 percent of the state populations.[142][143] Lutherans are prevalent in the Upper Midwest, especially in Michigan, Minnesota, the Dakotas, and Wisconsin with their large German and Scandinavian populations.[144] Southern Baptists compose about 15 percent of Missouri's population,[145] but much smaller percentages in other Midwestern states.

Judaism and Islam are collectively practiced by 2 percent of the population, with higher concentrations in major urban areas. 35 percent of Midwesterners attend religious services every week, and 69 percent attend at least a few times a year. People with no religious affiliation make up 22 percent of the Midwest's population.[146]

Education

Many Midwestern universities, both public and private, are members of the Association of American Universities (AAU), a bi-national organization of leading public and private research universities devoted to maintaining a strong system of academic research and education. Of the 62 members from the U.S. and Canada, 16 are located in the Midwest, including private schools Northwestern University, Case Western Reserve University, the University of Chicago, and Washington University in St. Louis. Member public institutions of the AAU include the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Indiana University Bloomington, the University of Iowa, Iowa State University, the University of Kansas, the University of Michigan, Michigan State University, the University of Minnesota, the University of Missouri, the Ohio State University, Purdue University, and the University of Wisconsin–Madison.[147]

Other notable major research-intensive public universities include the University of Cincinnati, the University of Illinois at Chicago, Wayne State University, Kansas State University, and the University of Nebraska–Lincoln.[148]

Numerous state university systems have established regional campuses statewide. The numerous state teachers colleges were upgraded into state universities after 1945.[149]

Other notable private institutions include the University of Notre Dame, John Carroll University, Saint Louis University, Butler University, Loyola University Chicago, DePaul University, Creighton University, Drake University, Marquette University, University of Dayton, and Xavier University. Local boosters, usually with a church affiliation, created numerous colleges in the mid-19th century.[150] In terms of national rankings, the most prominent today include Carleton College, Denison University, DePauw University, Earlham College, Grinnell College, Hamline University, Kalamazoo College, Kenyon College, Knox College, Macalester College, Lawrence University, Oberlin College, St. Olaf College, College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University, Mount Union University, Wabash College, Wheaton College, and The College of Wooster.[151]

Music

The heavy German immigration played a major role in establishing musical traditions, especially choral and orchestral music.[152] Czech and German traditions combined to sponsor the polka.[153]

The Southern Diaspora of the 20th century saw more than twenty million Southerners move throughout the country, many of whom moved into major Midwestern industrial cities such as Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, and St. Louis.[154] Along with them, they brought jazz to the Midwest, as well as blues, bluegrass, and rock and roll, with major contributions to jazz, funk, and R&B, and even new subgenres such as the Motown Sound and techno from Detroit[155] or house music from Chicago. In the 1920s, South Side Chicago was the base for Jelly Roll Morton (1890–1941). Kansas City developed its own jazz style.[156]

The electrified Chicago blues sound exemplifies the genre, as popularized by record labels Chess and Alligator and portrayed in such films as The Blues Brothers, Godfathers and Sons, and Adventures in Babysitting.

Rock and roll music was first identified as a new genre in 1951 by Cleveland disc jockey Alan Freed who began playing this music style while popularizing the term "rock and roll" to describe it.[157] By the mid-1950s, rock and roll emerged as a defined musical style in the United States, deriving most directly from the rhythm and blues music of the 1940s, which itself developed from earlier blues, boogie woogie, jazz, and swing music, and was also influenced by gospel, country and western, and traditional folk music. Freed's contribution in identifying rock as a new genre helped establish the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, located in Cleveland. Chuck Berry, a Midwesterner from St. Louis, was among the first successful rock and roll artists and influenced many other rock musicians.

Notable soul and R&B musicians associated with Motown that had their origins in the area include Aretha Franklin, The Supremes, Mary Wells, Four Tops, The Jackson 5, Smokey Robinson & the Miracles, Stevie Wonder, The Marvelettes, The Temptations, and Martha and the Vandellas. These artists achieved their greatest success in the 1960s and 1970s.

In the 1970s and 1980s, native Midwestern musicians such as John Mellencamp and Bob Seger found great success with a style of rock music that came to be known as heartland rock, characterized by lyrical themes that focused on and appealed to the Midwestern working class. Other successful Midwestern rock artists emerged during this time, including Cheap Trick, REO Speedwagon, Steve Miller, Styx, and Kansas.

Since the founding of rock 'n' roll music, an uncountable number of rock, soul, R&B, hip-hop, dance, blues, and jazz acts have emerged from Chicago onto the global and national music scene. Detroit has greatly contributed to the international music scene as a result of being the original home of the legendary Motown Records.

House Music, the first form of Electronic Dance Music, had its beginning in Chicago in the early 1980s, and by the late 1980s and the early 1990s house music had become popular on an international scale. House artists such as Frankie Knuckles, Marshall Jefferson and many others recorded early house music records at Chicago's Trax Records and many other local record labels. With the creation of house music in the city of Chicago, the first form of the globally popular electronic dance music genre was created. Techno had its start in Detroit in the late 1980s and early 1990s with techno pioneers such as Juan Atkins, Derrick May, and Kevin Saunderson. The genre, while popular in America, became much more popular overseas such as in Europe.[158]

Numerous classical composers live and have lived in midwestern states, including Easley Blackwood, Kenneth Gaburo, Salvatore Martirano, and Ralph Shapey (Illinois); Glenn Miller and Meredith Willson (Iowa); Leslie Bassett, William Bolcom, Michael Daugherty, and David Gillingham (Michigan); Donald Erb (Ohio); Dominick Argento and Stephen Paulus (Minnesota). Also notable is Peter Schickele, born in Iowa and partially raised in North Dakota, best known for his classical music parodies attributed to his alter ego of P. D. Q. Bach.

Sports

Professional sports leagues such as the National Football League (NFL), Major League Baseball (MLB), National Basketball Association (NBA), Women's National Basketball Association (WNBA), National Hockey League (NHL), Major League Soccer (MLS), and National Women's Soccer League (NWSL), have team franchises in following Midwestern cities:

- Chicago: Bears (NFL), Cubs, White Sox (MLB), Bulls (NBA), Sky (WNBA), Blackhawks (NHL), Fire FC (MLS), Red Stars (NWSL)

- Cincinnati: Bengals (NFL), Reds (MLB), FC Cincinnati (MLS)

- Cleveland: Browns (NFL), Guardians (MLB), Cavaliers (NBA)

- Columbus: Blue Jackets (NHL), Crew SC (MLS)

- Detroit: Lions (NFL), Tigers (MLB), Pistons (NBA), Red Wings (NHL)

- Green Bay: Packers (NFL)

- Indianapolis: Colts (NFL), Pacers (NBA), Fever (WNBA)

- Kansas City: Chiefs (NFL), Royals (MLB), Sporting (MLS)

- Milwaukee: Brewers (MLB), Bucks (NBA)

- Minneapolis–Saint Paul: Vikings (NFL), Twins (MLB), Timberwolves (NBA), Lynx (WNBA), Wild (NHL), United FC (MLS)

- St. Louis: Cardinals (MLB), Blues (NHL), City SC (MLS)

Popular teams include the St. Louis Cardinals (11 World Series titles), Cincinnati Reds (5 World Series titles), Chicago Bulls (6 NBA titles), the Detroit Pistons (3 NBA titles), the Minnesota Lynx (4 WNBA titles), the Green Bay Packers (4 Super Bowl titles, 13 total NFL championships), the Chicago Bears (1 Super Bowl title, 9 total NFL championships), the Cleveland Browns (4 AAFC championships, 4 NFL championships), the Detroit Red Wings (11 Stanley Cup titles), the Detroit Tigers (4 World Series titles), and the Chicago Blackhawks (6 Stanley Cup titles).

In NCAA college sports, the Big Ten Conference and the Big 12 Conference feature the largest concentration of top Midwestern Division I football and men's and women's basketball teams in the region, including the Illinois Fighting Illini, Indiana Hoosiers, Iowa Hawkeyes, Iowa State Cyclones, Kansas Jayhawks, Kansas State Wildcats, Michigan Wolverines, Michigan State Spartans, Minnesota Golden Gophers, Nebraska Cornhuskers, Northwestern Wildcats, Ohio State Buckeyes, Purdue Boilermakers, and the Wisconsin Badgers.

Other notable Midwestern college sports teams include the Akron Zips, Ball State Cardinals, Butler Bulldogs, Cincinnati Bearcats, Creighton Bluejays, Dayton Flyers, Grand Valley State Lakers, Indiana State Sycamores, Kent State Golden Flashes, Marquette Golden Eagles, Miami RedHawks, Milwaukee Panthers, Missouri Tigers, Missouri State Bears, Northern Illinois Huskies, North Dakota State Bison, Notre Dame Fighting Irish, Ohio Bobcats, South Dakota State Jackrabbits, Toledo Rockets, Western Michigan Broncos, Wichita State Shockers, and Xavier Musketeers. Of this second group of schools, Butler, Dayton, Indiana State, Missouri State, North Dakota State, and South Dakota State do not play top-level college football (all playing in the second-tier Division I FCS), and Creighton, Marquette, Milwaukee, Wichita State and Xavier do not sponsor football at all.[159]

The Milwaukee Mile hosted its first automobile race in 1903, and is one of the oldest tracks in the world, though as of 2019 is presently inactive. The Indianapolis Motor Speedway, opened in 1909, is a prestigious auto racing track which annually hosts the internationally famous Indianapolis 500-Mile Race (part of the IndyCar series), the Brickyard 400 (NASCAR), and the IndyCar Grand Prix (IndyCar series). The Road America and Mid-Ohio road courses opened in the 1950s and 1960s respectively. Other motorsport venues in the Midwest are Indianapolis Raceway Park (home of the NHRA U.S. Nationals), Michigan International Speedway, Chicagoland Speedway, Kansas Speedway, Gateway International Raceway, and the Iowa Speedway. The Kentucky Speedway is just outside the officially defined Midwest, but is linked with the region because the track is located in the Cincinnati metropolitan area.

Notable professional golf tournaments in the Midwest include the Memorial Tournament, BMW Championship and John Deere Classic.

Cultural overlap

Differences in the definition of the Midwest mainly split between the Great Plains region on one side, and the Great Lakes region on the other. Although some point to the small towns and agricultural communities in Kansas, Iowa, the Dakotas, and Nebraska of the Great Plains as representative of traditional Midwestern lifestyles and values, others assert that the industrial cities of the Great Lakes—with their histories of 19th century and early 20th century immigration, manufacturing base, and strong Catholic influence—are more representative of the Midwestern experience. In South Dakota, for instance, West River (the region west of the Missouri River) shares cultural elements with the western United States, while East River has more in common with the rest of the Midwest.[160]

Two other regions, Appalachia and the Ozark Mountains, overlap geographically with the Midwest—Appalachia in Southern Ohio and the Ozarks in Southern Missouri. The Ohio River has long been a boundary between North and South and between the Midwest and the Upper South. All of the lower Midwestern states, especially Missouri, have a major Southern components and influences, as they neighbor the Southern region. Historically, Missouri was a slave state before the American Civil War (1861–1865).

Western Pennsylvania, which contains the cities of Erie and Pittsburgh, share history with the Midwest, but overlap with Appalachia and the Northeast as well.[161]

Kentucky is not considered part of the Midwest; it is a northern region of the South, although certain northern parts of the state could have possibly been grouped with the Midwest in a geographical context, even though it is geographically in the Southeast overall.[162] Kentucky is categorized as Southern by the US Census Bureau due to its industries and especially from a historical and cultural standpoint with the majority of the state having a thoroughly majority Southern accent, demographic, history, and culture in line with her sister states of Virginia and Tennessee and even the areas that have certain Midwestern influences tend to be mixed with the native Southern culture of the area.[163][164]

In addition to intra-American regional overlaps, the Upper Peninsula of Michigan has historically had strong cultural ties to Canada, partly as a result of early settlement by French Canadians. Moreover, the Yooper accent shares some traits with Canadian English, further demonstrating transnational cultural connections. Similar but less pronounced mutual Canadian-American cultural influence occurs throughout the Great Lakes region.

Linguistic characteristics

The accents of the region are generally distinct from those of the American South and of the urban areas of the American Northeast. To a lesser degree, they are also distinct from the accent of the American West.

The accent characteristic of most of the Midwest is popularly considered to be that of "standard" American English or General American. This accent is typically preferred by many national radio and television producers. Linguist Thomas Bonfiglio argues that, "American English pronunciation standardized as 'network standard' or, informally, 'Midwestern' in the 20th century." He identifies radio as the chief factor.[165][166]

Currently, many cities in the Great Lakes region are undergoing the Northern cities vowel shift away from the standard pronunciation of vowels.[167]

The dialect of Minnesota, western Wisconsin, much of North Dakota and Michigan's Upper Peninsula is referred to as the Upper Midwestern Dialect (or "Minnesotan"), and has Scandinavian and Canadian influences.

Missouri has elements of three dialects, specifically: Northern Midland, in the extreme northern part of the state, with a distinctive variation in St. Louis and the surrounding area; Southern Midland, in the majority of the state; and Southern, in the southwestern and southeastern parts of the state, with a bulge extending north in the central part, to include approximately the southern one-third.[168]

Health

The rate of potentially preventable hospital discharges in the Midwestern United States fell from 2005 to 2011 for overall conditions, acute conditions, and chronic conditions.[169]

Euchre

Euchre, a trick-taking card game, remains popular in the Midwest, particularly in Michigan, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Kentucky, and Pennsylvania.[170]

Population centers

Major metropolitan areas

|

|

|

|

State population

| State | 2020 Census | 2010 Census | Change | Area | Density |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iowa | 3,190,369 | 3,046,355 | +4.73% | 55,857.09 sq mi (144,669.2 km2) | 57/sq mi (22/km2) |

| Kansas | 2,937,880 | 2,853,118 | +2.97% | 81,758.65 sq mi (211,753.9 km2) | 36/sq mi (14/km2) |

| Missouri | 6,154,913 | 5,988,927 | +2.77% | 68,741.47 sq mi (178,039.6 km2) | 90/sq mi (35/km2) |

| Nebraska | 1,961,504 | 1,826,341 | +7.40% | 76,824.11 sq mi (198,973.5 km2) | 26/sq mi (10/km2) |

| North Dakota | 779,094 | 672,591 | +15.83% | 69,000.74 sq mi (178,711.1 km2) | 11/sq mi (4/km2) |

| South Dakota | 886,667 | 814,180 | +8.90% | 75,810.94 sq mi (196,349.4 km2) | 12/sq mi (5/km2) |

| Plains | 15,910,427 | 15,201,512 | +4.66% | 427,993.00 sq mi (1,108,496.8 km2) | 37/sq mi (14/km2) |

| Illinois | 12,812,508 | 12,830,632 | −0.14% | 55,518.89 sq mi (143,793.3 km2) | 231/sq mi (89/km2) |

| Indiana | 6,785,528 | 6,483,802 | +4.65% | 35,826.08 sq mi (92,789.1 km2) | 189/sq mi (73/km2) |

| Michigan | 10,077,331 | 9,883,640 | +1.96% | 56,538.86 sq mi (146,435.0 km2) | 178/sq mi (69/km2) |

| Minnesota | 5,706,494 | 5,303,925 | +7.59% | 79,626.68 sq mi (206,232.2 km2) | 72/sq mi (28/km2) |

| Ohio | 11,799,448 | 11,536,504 | +2.28% | 40,860.66 sq mi (105,828.6 km2) | 289/sq mi (111/km2) |

| Wisconsin | 5,893,718 | 5,686,986 | +3.64% | 54,157.76 sq mi (140,268.0 km2) | 109/sq mi (42/km2) |