Cholecalciferol

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌkoʊləkælˈsɪfərɒl/ |

| Other names | vitamin D3, activated 7-dehydrocholesterol |

IUPAC name

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Vitamin[1] |

| WHO AWaRe | UnlinkedWikibase error: ⧼unlinkedwikibase-error-statements-entity-not-set⧽ |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth, intramuscular injection |

| Defined daily dose | 20 ug[1] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Professional Drug Facts |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status |

|

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C27H44O |

| Molar mass | 384.648 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 83 to 86 °C (181 to 187 °F) |

| Boiling point | 496.4 °C (925.5 °F) |

| Solubility in water | Practically insoluble in water, freely soluble in ethanol, methanol and some other organic solvents. Slightly soluble in vegetable oils. |

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

Cholecalciferol, also known as vitamin D3 and colecalciferol, is a type of vitamin D which is made by the skin when exposed to sunlight; it is also found in some foods and can be taken as a dietary supplement.[2] It is used to treat and prevent vitamin D deficiency and associated diseases, including rickets.[3][4] It is also used for familial hypophosphatemia, hypoparathyroidism that is causing low blood calcium, and Fanconi syndrome.[4][5] Vitamin-D supplements may not be effective in people with severe kidney disease.[6] It is usually taken by mouth.[5]

Excessive doses in humans can result in vomiting, constipation, weakness, and confusion.[7] Other risks include kidney stones.[6] Doses greater than 40,000 IU (1,000 μg) per day are generally required before high blood calcium occurs.[8] Normal doses, 800–2000 IU per day, are safe in pregnancy.[7]

Cholecalciferol is made in the skin following UVB light exposure.[9] It is converted in the liver to calcifediol (25-hydroxyvitamin D) which is then converted in the kidney to calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D).[9] One of its actions is to increase the uptake of calcium by the intestines.[7] It is found in food such as some fish, beef liver, eggs, and cheese.[10][11] Certain foods such as milk, fruit juice, yogurt, and margarine also may have cholecalciferol added to them in some countries including the United States.[10][11]

Cholecalciferol was first described in 1936.[12] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[13] Cholecalciferol is available as a generic medication and over the counter.[5] Cholecalciferol is also used at much higher doses to kill rodents.[14][15]

Medical uses

Vitamin D deficiency

Cholecalciferol is a form of vitamin D which is naturally synthesized in skin and functions as a pro-hormone, being converted to calcitriol. This is important for maintaining calcium levels and promoting bone health and development.[9] As a medication, cholecalciferol may be taken as a dietary supplement to prevent or to treat vitamin D deficiency. One gram is 40,000,000 (40x106) IU, equivalently 1 IU is 0.025 µg. Dietary reference intake values for vitamin D (cholecalciferol and/or ergocalciferol) have been established and recommendations vary depending on the country:

- In the US: 15 µg/d (600 IU per day) for all individuals (males, females, pregnant/lactating women) between the ages of 1 and 70 years old, inclusive. For all individuals older than 70 years, 20 µg/d (800 IU per day) is recommended.[16]

- In the EU: 20 µg/d (800 IU per day)

- In France: 25 µg/d (1000 IU per day)

Many question whether the current recommended intake is sufficient to meet physiological needs. Individuals without regular sun exposure, the obese, and darker skinned individuals all have lower blood levels and require more supplementation.

The Institute of Medicine in 2010 recommended a maximum uptake of vitamin D of 4,000 IU/day, finding that the dose for lowest observed adverse effect level is 40,000 IU daily for at least 12 weeks,[17] and that there was a single case of toxicity above 10,000 IU after more than 7 years of daily intake; this case of toxicity occurred in circumstances that have led other researchers to dispute it as a credible case to consider when making vitamin D intake recommendations.[17] Patients with severe vitamin D deficiency will require treatment with a loading dose; its magnitude can be calculated based on the actual serum 25-hydroxy-vitamin D level and body weight.[18]

There are conflicting reports concerning the relative effectiveness of cholecalciferol (D3) versus ergocalciferol (D2), with some studies suggesting less efficacy of D2, and others showing no difference. There are differences in absorption, binding and inactivation of the two forms, with evidence usually favoring cholecalciferol in raising levels in blood, although more research is needed.[19]

A much less common use of cholecalciferol therapy in rickets utilizes a single large dose and has been called stoss therapy.[20][21][22] Treatment is given either orally or by intramuscular injection of 300,000 IU (7,500 µg) to 500,000 IU (12,500 µg = 12.5 mg), in a single dose, or sometimes in two to four divided doses. There are concerns about the safety of such large doses.[22]

Other diseases

A meta-analysis of 2007 concluded that daily intake of 1000 to 2000 IU per day of vitamin D3 could reduce the incidence of colorectal cancer with minimal risk.[23] Also a 2008 study published in Cancer Research has shown the addition of vitamin D3 (along with calcium) to the diet of some mice fed a regimen similar in nutritional content to a new Western diet with 1000 IU cholecalciferol per day prevented colon cancer development.[24] In humans, with 400 IU daily, there was no effect of cholecalciferol supplements on the risk of colorectal cancer.[25]

Supplements are not recommended for prevention of cancer as any effects of cholecalciferol are very small.[26] Although correlations exist between low levels of blood serum cholecalciferol and higher rates of various cancers, multiple sclerosis, tuberculosis, heart disease, and diabetes,[27] the consensus is that supplementing levels is not beneficial.[28] It is thought that tuberculosis may result in lower levels.[29] It, however, is not entirely clear how the two are related.[30]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 20 micrograms by mouth.[1] When used to treat vitamin D deficiency in those over the age of 11, 6,000 IU daily for three months or 300,000 IU as a single dose may be used.[31] In children 1 to 12 years old 3,000 to 6,000 IU a day for three months or 150,000 as a single dose may be used.[31] For those under a year the dose is 2,000 IU a day for 3 months.[31]

for prevention in newborns 400 to 1,200 IU a day for the first 6 month of life may be used.[31] In pregnancy 100,000 IU may be given in the 24th to 30th week to prevent vitamin D deficiency.[31]

Biochemistry

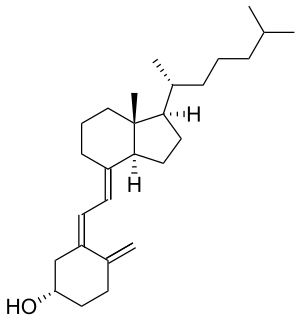

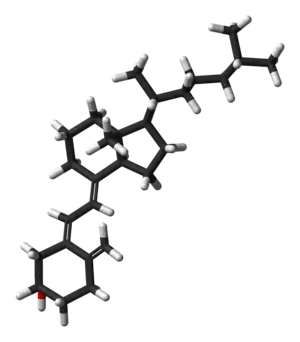

Structure

Cholecalciferol is one of the five forms of vitamin D.[32] Cholecalciferol is a secosteroid, that is, a steroid molecule with one ring open.[33]

Mechanism of action

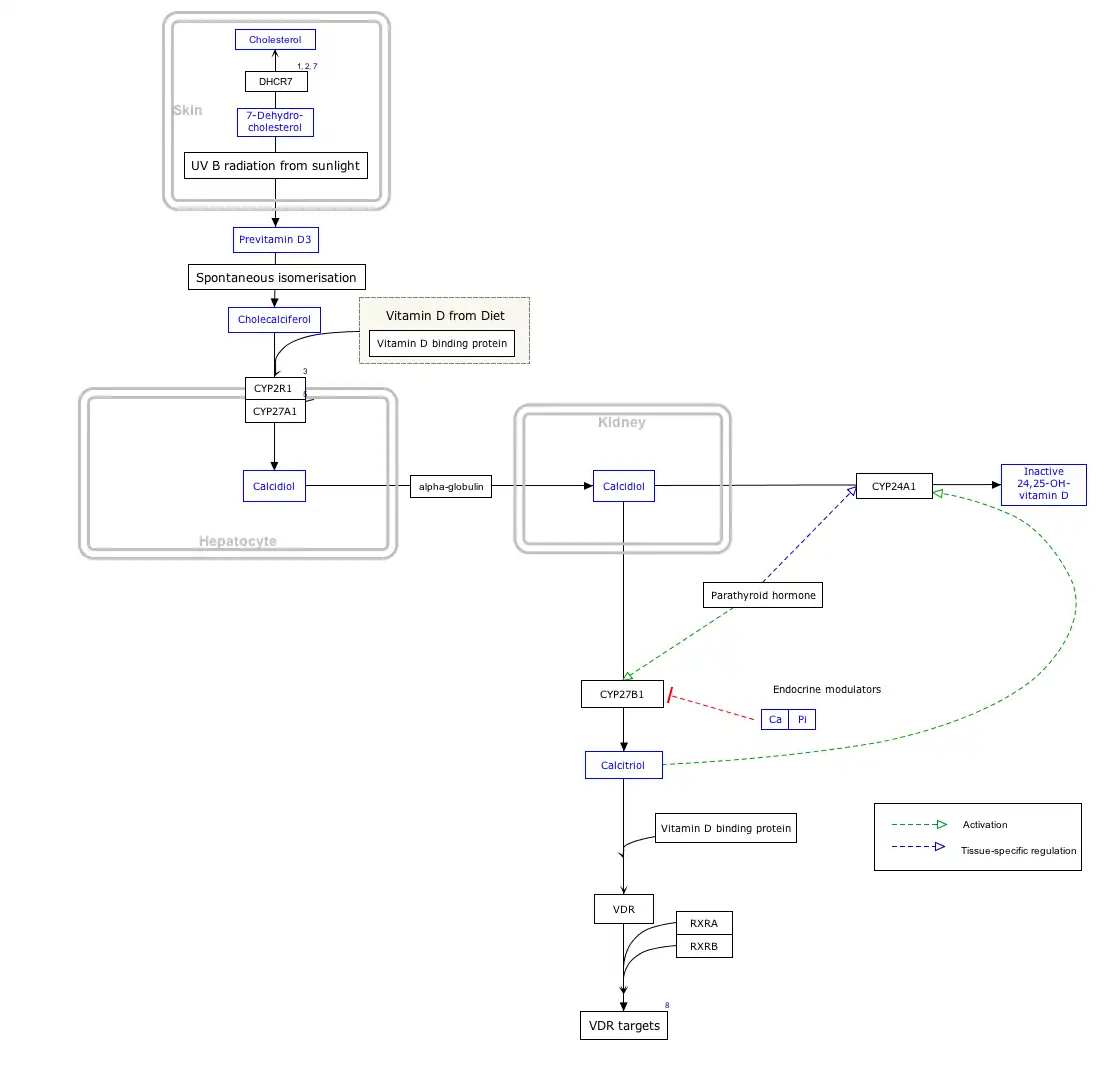

By itself cholecalciferol is inactive. It is converted to its active form by two hydroxylations: the first in the liver, by CYP2R1 or CYP27A1, to form 25-hydroxycholecalciferol (calcifediol, 25-OH vitamin D3). The second hydroxylation occurs mainly in the kidney through the action of CYP27B1 to convert 25-OH vitamin D3 into 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol (calcitriol, 1,25-(OH)2vitamin D3). All these metabolites are bound in blood to the vitamin D-binding protein. The action of calcitriol is mediated by the vitamin D receptor, a nuclear receptor which regulates the synthesis of hundreds of proteins and is present in virtually every cell in the body.[9]

Biosynthesis

Click on icon in lower right corner to open. Click on genes, proteins and metabolites below to link to respective articles. [§ 1]

- ↑ The interactive pathway map can be edited at WikiPathways: "VitaminDSynthesis_WP1531".

7-Dehydrocholesterol is the precursor of cholecalciferol.[9] Within the epidermal layer of skin, 7-dehydrocholesterol undergoes an electrocyclic reaction as a result of UVB light at wavelengths between 290 and 315 nm, with peak synthesis occurring between 295 and 300 nm.[34] This results in the opening of the vitamin precursor B-ring through a conrotatory pathway making previtamin D3 (pre-cholecalciferol).[35] In a process which is independent of UV light, the pre-cholecalciferol then undergoes a [1,7] antarafacial sigmatropic rearrangement [36] and therein finally isomerizes to form vitamin D3.

The active UVB wavelengths are present in sunlight, and sufficient amounts of cholecalciferol can be produced with moderate exposure of the skin, depending on the strength of the sun.[34] Time of day, season, and altitude affect the strength of the sun, and pollution, cloud cover or glass all reduce the amount of UVB exposure. Exposure of face, arms and legs, averaging 5–30 minutes twice per week, may be sufficient, but the darker the skin, and the weaker the sunlight, the more minutes of exposure are needed. Vitamin D overdose is impossible from UV exposure; the skin reaches an equilibrium where the vitamin degrades as fast as it is created.[34]

Cholecalciferol can be produced in skin from the light emitted by the UV lamps in tanning beds, which produce ultraviolet primarily in the UVA spectrum, but typically produce 4% to 10% of the total UV emissions as UVB. Levels in blood are higher in frequent uses of tanning salons.[34]

Whether cholecalciferol and all forms of vitamin D are by definition "vitamins" can be disputed, since the definition of vitamins includes that the substance cannot be synthesized by the body and must be ingested. Cholecalciferol is synthesized by the body during UVB radiation exposure.[9]

The three steps in the synthesis and activation of vitamin D3 are regulated as follows:

- Cholecalciferol is synthesized in the skin from 7-dehydrocholesterol under the action of ultraviolet B (UVB) light. It reaches an equilibrium after several minutes depending on the intensity of the UVB in the sunlight - determined by latitude, season, cloud cover, and altitude - and the age and degree of pigmentation of the skin.

- Hydroxylation in the endoplasmic reticulum of liver hepatocytes of cholecalciferol to calcifediol (25-hydroxycholecalciferol) by 25-hydroxylase is loosely regulated, if at all, and blood levels of this molecule largely reflect the amount of cholecalciferol produced in the skin combined with any vitamin D2 or D3 ingested.

- Hydroxylation in the kidneys of calcifediol to calcitriol by 1-alpha-hydroxylase is tightly regulated: it is stimulated by parathyroid hormone and serves as the major control point in the production of the active circulating hormone calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3).[9]

Industrial production

Cholecalciferol is produced industrially for use in vitamin supplements and to fortify foods. As a pharmaceutical drug it is called cholecalciferol (USAN) or colecalciferol (INN, BAN). It is produced by the ultraviolet irradiation of 7-dehydrocholesterol extracted from lanolin found in sheep's wool.[37] Cholesterol is extracted from wool grease and wool wax alcohols obtained from the cleaning of wool after shearing. The cholesterol undergoes a four-step process to make 7-dehydrocholesterol, the same compound that is produced in the skin of animals. The 7-dehydrocholesterol is then irradiated with ultraviolet light. Some unwanted isomers are formed during irradiation: these are removed by various techniques, leaving a resin which melts at about room temperature and usually has a potency of 25,000,000 to 30,000,000 International Units per gram.

Cholecalciferol is also produced industrially for use in vitamin supplements from lichens, which is suitable for vegans.[38][39]

Stability

Cholecalciferol is very sensitive to UV radiation and will rapidly, but reversibly, break down to form supra-sterols, which can further irreversibly convert to ergosterol.

Society and culture

Cost

In 2015, the wholesale cost in Costa Rica is about US$2.15 per 30 ml bottle of 10,000 IU/ml.[40] In the United States, human treatment costs less than US$25 per month.[5] In the UK, the cost to the NHS in 2018 for one month's treatment can be less than 3 GBP.[41]

Rodenticide

Rodents are somewhat more susceptible to high doses than other species, and cholecalciferol has been used in poison bait for the control of these pests.[42][15]

The mechanism of high dose cholecalciferol is that it can produce "hypercalcemia, which results in systemic calcification of soft tissue, leading to kidney failure, cardiac abnormalities, hypertension, CNS depression, and GI upset. Signs generally develop within 18-36 hr of ingestion and can include depression, loss of appetite, polyuria, and polydipsia."[14] High-dose cholecalciferol will tend to rapidly accumulate in adipose tissue yet release more slowly[43] which will tend to delay time of death for several days from the time that high-dose bait is introduced.[42]

In New Zealand, possums have become a significant pest animal. For possum control, cholecalciferol has been used as the active ingredient in lethal baits.[44] The LD50 is 16.8 mg/kg, but only 9.8 mg/kg if calcium carbonate is added to the bait.[45][46] Kidneys and heart are target organs.[47]

It has been claimed that the compound is less toxic to non-target species. However, in practice it has been found that use of cholecalciferol in rodenticides represents a significant hazard to other animals, such as dogs and cats.[14]

See also

- Hypervitaminosis D, Vitamin D poisoning

- Ergocalciferol, vitamin D2.

- 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 1-alpha-Hydroxylase, a kidney enzyme that converts calcifediol to calcitriol.

References

- 1 2 3 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 18 September 2020. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ↑ Coulston, Ann M.; Boushey, Carol; Ferruzzi, Mario (2013). Nutrition in the Prevention and Treatment of Disease. Academic Press. p. 818. ISBN 9780123918840. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ↑ British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. pp. 703–704. ISBN 9780857111562.

- 1 2 World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- 1 2 3 4 Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 231. ISBN 9781284057560.

- 1 2 "Aviticol 1 000 IU Capsules - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) - (eMC)". www.medicines.org.uk. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Cholecalciferol (Professional Patient Advice) - Drugs.com". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ↑ Vieth R (May 1999). "Vitamin D supplementation, 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations, and safety" (PDF). The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 69 (5): 842–56. doi:10.1093/ajcn/69.5.842. PMID 10232622. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 July 2012. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Norman AW (August 2008). "From vitamin D to hormone D: fundamentals of the vitamin D endocrine system essential for good health". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 88 (2): 491S–499S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/88.2.491S. PMID 18689389.

- 1 2 "Office of Dietary Supplements - Vitamin D". ods.od.nih.gov. 11 February 2016. Archived from the original on 31 December 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- 1 2 Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and, Calcium; Ross, AC; Taylor, CL; Yaktine, AL; Del Valle, HB (2011). Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D (PDF). doi:10.17226/13050. ISBN 978-0-309-16394-1. PMID 21796828. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ↑ Fischer, Janos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 451. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- 1 2 3 "Merck Veterinary Manual - Rodenticide Poisoning: Introduction". Archived from the original on 17 January 2007.

- 1 2 Rizor, Suzanne E.; Arjo, Wendy M.; Bulkin, Stephan; Nolte, Dale L. Efficacy of Cholecalciferol Baits for Pocket Gopher Control and Possible Effects on Non-Target Rodents in Pacific Northwest Forests. Vertebrate Pest Conference (2006). USDA. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

0.15% cholecalciferol bait appears to have application for pocket gopher control.' Cholecalciferol can be a single high-dose toxicant or a cumulative multiple low-dose toxicant.

- ↑ DRIs for Calcium and Vitamin D Archived 2010-12-24 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Vieth R (May 1999). "Vitamin D supplementation, 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations, and safety". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 69 (5): 842–56. doi:10.1093/ajcn/69.5.842. PMID 10232622.

- ↑ van Groningen L, Opdenoordt S, van Sorge A, Telting D, Giesen A, de Boer H (April 2010). "Cholecalciferol loading dose guideline for vitamin D-deficient adults". European Journal of Endocrinology. 162 (4): 805–11. doi:10.1530/EJE-09-0932. PMID 20139241.

- ↑ Tripkovic L, Lambert H, Hart K, Smith CP, Bucca G, Penson S, et al. (June 2012). "Comparison of vitamin D2 and vitamin D3 supplementation in raising serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 95 (6): 1357–64. doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.031070. PMC 3349454. PMID 22552031.

- ↑ Shah BR, Finberg L (September 1994). "Single-day therapy for nutritional vitamin D-deficiency rickets: a preferred method". The Journal of Pediatrics. 125 (3): 487–90. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(05)83303-7. PMID 8071764.

- ↑ Chatterjee D, Swamy MK, Gupta V, Sharma V, Sharma A, Chatterjee K (March 2017). "Safety and Efficacy of Stosstherapy in Nutritional Rickets". Journal of Clinical Research in Pediatric Endocrinology. 9 (1): 63–69. doi:10.4274/jcrpe.3557. PMC 5363167. PMID 27550890.

- 1 2 Bothra M, Gupta N, Jain V (June 2016). "Effect of intramuscular cholecalciferol megadose in children with nutritional rickets". Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology & Metabolism. 29 (6): 687–92. doi:10.1515/jpem-2015-0031. PMID 26913455.

- ↑ Gorham ED, Garland CF, Garland FC, Grant WB, Mohr SB, Lipkin M, et al. (March 2007). "Optimal vitamin D status for colorectal cancer prevention: a quantitative meta analysis". American Journal of Preventive Medicine (Meta-Analysis). 32 (3): 210–6. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2006.11.004. PMID 17296473.

- ↑ Yang K, Kurihara N, Fan K, Newmark H, Rigas B, Bancroft L, et al. (October 2008). "Dietary induction of colonic tumors in a mouse model of sporadic colon cancer". Cancer Research. 68 (19): 7803–10. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1209. PMID 18829535.

- ↑ Wactawski-Wende J, Kotchen JM, Anderson GL, Assaf AR, Brunner RL, O'Sullivan MJ, et al. (February 2006). "Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of colorectal cancer". The New England Journal of Medicine. 354 (7): 684–96. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055222. PMID 16481636. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- ↑ Bjelakovic G, Gluud LL, Nikolova D, Whitfield K, Wetterslev J, Simonetti RG, et al. (January 2014). "Vitamin D supplementation for prevention of mortality in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD007470. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd007470.pub3. PMID 24414552.

- ↑ Garland CF, Garland FC, Gorham ED, Lipkin M, Newmark H, Mohr SB, Holick MF (February 2006). "The role of vitamin D in cancer prevention". American Journal of Public Health. 96 (2): 252–61. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.045260. PMC 1470481. PMID 16380576.

- ↑ Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, Aloia JF, Brannon PM, Clinton SK, et al. (January 2011). "The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 96 (1): 53–8. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-2704. PMC 3046611. PMID 21118827.

- ↑ Gou X, Pan L, Tang F, Gao H, Xiao D (August 2018). "The association between vitamin D status and tuberculosis in children: A meta-analysis". Medicine. 97 (35): e12179. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000012179. PMC 6392646. PMID 30170465.

- ↑ Keflie TS, Nölle N, Lambert C, Nohr D, Biesalski HK (October 2015). "Vitamin D deficiencies among tuberculosis patients in Africa: A systematic review". Nutrition. 31 (10): 1204–12. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2015.05.003. PMID 26333888.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "COLECALCIFEROL = VITAMIN D3 oral - Essential drugs". medicalguidelines.msf.org. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ↑ "cholecalciferol" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ↑ "About Vitamin D". University of California, Riverside. November 2011. Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Wacker M, Holick MF (January 2013). "Sunlight and Vitamin D: A global perspective for health". Dermato-Endocrinology. 5 (1): 51–108. doi:10.4161/derm.24494. PMC 3897598. PMID 24494042.

- ↑ MacLaughlin JA, Anderson RR, Holick MF (May 1982). "Spectral character of sunlight modulates photosynthesis of previtamin D3 and its photoisomers in human skin". Science. 216 (4549): 1001–3. doi:10.1126/science.6281884. PMID 6281884. S2CID 23011680.

- ↑ Okamura WH, Elnagar HY, Ruther M, Dobreff S (1993). "Thermal [1,7]-sigmatropic shift of previtamin D3 to vitamin D3: synthesis and study of pentadeuterio derivatives". Journal of Organic Chemistry. 58 (3): 600–610. doi:10.1021/jo00055a011.

- ↑ Vitamin D3 Story. Archived 2012-01-22 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ↑ "Vitashine Vegan Vitamin D3 Supplements". Archived from the original on 4 March 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ↑ Wang T, Bengtsson G, Kärnefelt I, Björn LO (September 2001). "Provitamins and vitamins D₂and D₃in Cladina spp. over a latitudinal gradient: possible correlation with UV levels". Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology. B, Biology. 62 (1–2): 118–22. doi:10.1016/s1011-1344(01)00160-9. PMID 11693362. Archived from the original on 28 October 2012.

- ↑ "Single Drug Information | International Medical Products Price Guide". mshpriceguide.org. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ↑ NICE. "Colecalciferol". Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- 1 2 CHOLECALCIFEROL: A UNIQUE TOXICANT FOR RODENT CONTROL. Proceedings of the Eleventh Vertebrate Pest Conference (1984). University of Nebraska Lincoln. March 1984. Archived from the original on 27 August 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

Cholecalciferol is an acute (single-feeding) and/or chronic (multiple-feeding) rodenticide toxicant with unique activity for controlling commensal rodents including anticoagulant-resistant rats. Cholecalciferol differs from conventional acute rodenticides in that no bait shyness is associated with consumption and time to death is delayed, with first dead rodents appearing 3-4 days after treatment.

- ↑ Brouwer, D. A. Janneke; van Beek, Jackelien; Ferwerda, Harri; Brugman, Astrid M.; van der Klis, Fiona R. M.; et al. (9 March 2007). "Rat adipose tissue rapidly accumulates and slowly releases an orally-administered high vitamin D dose". British Journal of Nutrition. 79 (6): 527–532. doi:10.1079/BJN19980091. PMID 9771340.

We investigated the effect of oral high-dose cholecalciferol on plasma and adipose tissue cholecalciferol and its subsequent release, and on plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D). ... We conclude that orally-administered cholecalciferol rapidly accumulates in adipose tissue and that it is very slowly released while there is energy balance.

- ↑ "Pestoff DECAL Possum Bait - Rentokil Initial Safety Data Sheets" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ↑ Morgan D (2006). "Field efficacy of cholecalciferol gel baits for possum (Trichosurus vulpecula) control". New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 33 (3): 221–8. doi:10.1080/03014223.2006.9518449.

- ↑ Jolly SE, Henderson RJ, Frampton C, Eason CT (1995). "Cholecalciferol Toxicity and Its Enhancement by Calcium Carbonate in the Common Brushtail Possum". Wildlife Research. 22 (5): 579–83. doi:10.1071/WR9950579.

- ↑ "Kiwicare Material Safety Data Sheet" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 February 2013.

External links

| External sites: |

|

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

- NIST Chemistry WebBook page for cholecalciferol Archived 28 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Vitamin D metabolism, sex hormones, and male reproductive function. Archived 18 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine