Gillespie syndrome

| Gillespie syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Aniridia-cerebellar ataxia-intellectual disability, Partial aniridia-cerebellar ataxia-oligophrenia | |

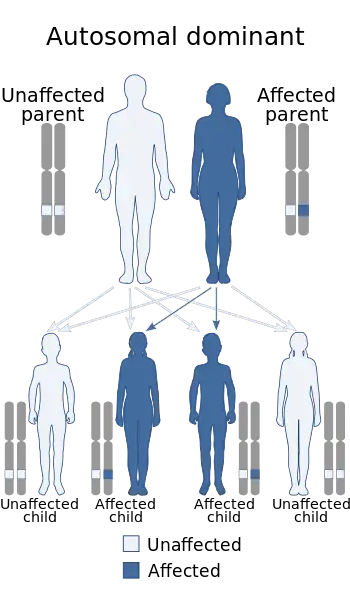

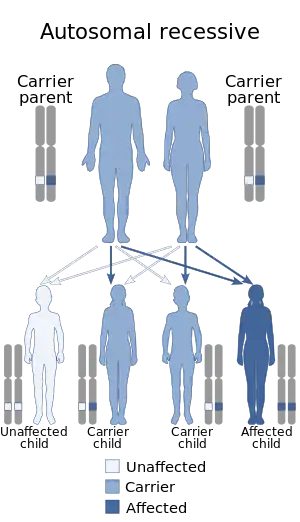

Gillespie syndrome can be inherited in either an autosomal dominant (left) or autosomal recessive (right) pattern. | |

Gillespie syndrome, also called aniridia, cerebellar ataxia and mental deficiency,[1][2][3] is a rare genetic disorder. The disorder is characterized by partial aniridia (meaning that part of the iris is missing), ataxia (motor and coordination problems), and, in most cases, intellectual disability. It is heterogeneous, inherited in either an autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive manner.[4] Gillespie syndrome was first described by American ophthalmologist Fredrick Gillespie in 1965.[1][3]

Signs and symptoms

The combination of muscular hypotonia and fixed dilated pupils in infancy is suspicious of Gillespie syndrome.[5] Early onset partial aniridia, cerebellar ataxia, and mental retardation are hallmark of syndrome.[6] The iris abnormality is specific and seems pathognomonic of Gillespie syndrome.[6] The aniridia consisting of a superior coloboma and inferior iris hypoplasia, foveomacular dysplasia.[7]

Atypical Gillespie syndrome associated with bilateral ptosis, exotropia, correctopia, iris hypoplasia, anterior capsular lens opacities, foveal hypoplasia, retinal vascular tortuosity, and retinal hypopigmentation.[8]

Neurological signs are nystagmus, mild craniofacial asymmetry, axial hypotonia, developmental delay, and mild mental retardation.[6][7] Mariën P did not support the prevailing view of a global mental retardation as a cardinal feature of Gillespie syndrome but primarily reflect cerebellar induced neurobehavioral dysfunctions following disruption of the cerebrocerebellar anatomical circuitry that closely resembles the "cerebellar cognitive and affective syndrome" (CeCAS).[9]

Congenital pulmonary stenosis and helix dysplasia can be associated.[5]

Genetics

Gillespie syndrome is a heterogeneous disorder, and can be inherited in either an autosomal dominant or recessive manner.[4][6] Autosomal dominant inheritance indicates that the defective gene responsible for a disorder is located on an autosome, and only one copy of the gene is sufficient to cause the disorder, when inherited from a parent who has the disorder.

Autosomal recessive inheritance means the defective gene responsible for the disorder is located on an autosome, but two copies of the defective gene (one inherited from each parent) are required in order to be born with the disorder. The parents of an individual with an autosomal recessive disorder both carry one copy of the defective gene, but usually do not experience any signs or symptoms of the disorder.

PAX6 gene analysis can also be helpful to distinguish between autosomal dominant aniridia and Gillespie syndrome.[5] However atypical Gillespie syndrome is associated mutation with PAX6 gene.[2][8]

To elucidate the underlying genetic defects karyotyping and the search for de novo translocations especially of chromosome X and 11 should be performed.[5]

This condition is caused by mutations in the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 1 (ITPR1) gene.[10] This gene is located on the short arm of chromosome 3 (3p26.1). Mutations in this gene have also been associated with spinocerebellar ataxia type 15 and 29.

Diagnosis

Brain MRI shows vermis atrophy or hypoplasic.[12] Cerebral and cerebellar atrophy with white matter changes in some cases.[6]

Treatment

In terms of management of Gillespie syndrome we find the following is included:[13]

History

- 1964 – GILLESPIE FD first described in two siblings with aniridia, cerebellar ataxia, and mental retardation.[1]

- 1971 – Sarsfield, J. K. described more cases in a family with normal NCV and muscle biopsy.[14]

- 1997 – Nelson J reported diffuse MRI abnormality in Cerebral and cerebellar atrophy with white matter changes suggested more diffuse disease.[6]

- 1998 – Dollfus H reported a patient with a phenotype suggestive of a chromosomal abnormality.[7]

- 2008 – Mariën P found limited cognitive deficit that closely resembles the "cerebellar cognitive and affective syndrome" (CeCAS).[9]

References

- 1 2 3 Gillespie, FD (Mar 1965). "Aniridia, cerebellar ataxia, and oligophrenia in siblings". Archives of Ophthalmology. 73 (3): 338–341. doi:10.1001/archopht.1965.00970030340008. PMID 14246186.

- 1 2 Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 206700

- 1 2 synd/2006 at Who Named It?

- 1 2 Defreyn, A; Maugery, J; Chabrier, S; Coullet, J (Jan 2007). "Syndrome de Gillespie : un cas rare d'aniridie congénitale". Journal Français d'Ophthalmologie (in French). 30 (1): e1. doi:10.1016/s0181-5512(07)89554-4. PMID 17287663. Archived from the original on 2018-12-18. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - 1 2 3 4 Kieslich, M; Vanselow, K; Wildhardt, G; Gebhardt, B; Weis, R; Böhles, H (Apr 2001). "[Present limitations of molecular biological diagnostics in Gillespie syndrome]". Klinische Pädiatrie. 213 (2): 47–49. doi:10.1055/s-2001-12875. PMID 11305191.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Nelson, J (Aug 1997). "Gillespie syndrome: a report of two further cases". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 71 (2): 134–8. doi:10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19970808)71:2<134::aid-ajmg3>3.0.co;2-y. PMID 9217210.

- 1 2 3 Dollfus, H (Mar 1998). "Gillespie syndrome phenotype with a t(X;11)(p22.32;p12) de novo translocation". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 125 (3): 397–9. doi:10.1016/s0002-9394(99)80157-3. PMID 9512164.

- 1 2 Ticho, BH; Hilchie-Schmidt, C; Egel, RT; Traboulsi, EI; Howarth, RJ; Robinson, D (Dec 2006). "Ocular findings in Gillespie-like syndrome: association with a new PAX6 mutation". Ophthalmic Genetics. 27 (4): 145–149. doi:10.1080/13816810600976897. PMID 17148041. S2CID 21415333.

- 1 2 Mariën, P; Brouns, R; Engelborghs, S; Wackenier, P; Verhoeven, J; Ceulemans, B; De Deyn, PP (Jan 2008). "Cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome without global mental retardation in two relatives with Gillespie syndrome". Cortex. 44 (1): 54–67. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2005.12.001. PMID 18387531. S2CID 16768408.

- ↑ Paganini L, Pesenti C, Milani D, Fontana L, Motta S, Sirchia SM, Scuvera G, Marchisio P, Esposito S, Cinnante CM, Tabano SM, Miozzo MR (2018) A novel splice site variant in ITPR1 gene underlying recessive Gillespie syndrome. Am J Med Genet A doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38704

- ↑ De Silva, D; Williamson, KA; Dayasiri, KC; Suraweera, N; Quinters, V; Abeysekara, H; Wanigasinghe, J; De Silva, D; De Silva, H (24 September 2018). "Gillespie syndrome in a South Asian child: a case report with confirmation of a heterozygous mutation of the ITPR1 gene and review of the clinical and molecular features". BMC pediatrics. 18 (1): 308. doi:10.1186/s12887-018-1286-5. PMID 30249237. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ↑ Boughamoura, L; Yacoub, M; Abroug, M; Chabchoub, I; Bouguezzi, R; Charfeddine, L; Amri, F; Essoussi, A-S (Oct 2006). "[Gillespie syndrome: 2 familial cases]". Archives de Pédiatrie. 13 (10): 1323–1325. doi:10.1016/j.arcped.2006.06.028. PMID 16919425.

- ↑ RESERVED, INSERM US14-- ALL RIGHTS. "Orphanet: Aniridia cerebellar ataxia intellectual disability syndrome". www.orpha.net. Archived from the original on 3 October 2022. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ↑ Sarsfield, JK (Aug 1971). "The syndrome of congenital cerebellar ataxia, aniridia and mental retardation". Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 13 (4): 508–11. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.1971.tb03057.x. PMID 5558750. S2CID 28822017.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|

- Gillespie syndrome at MedlinePlus Archived 2022-04-24 at the Wayback Machine