Papillorenal syndrome

| Papillorenal syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: so called renal-coloboma syndrome or isolated renal hypoplasia,[1] | |

| |

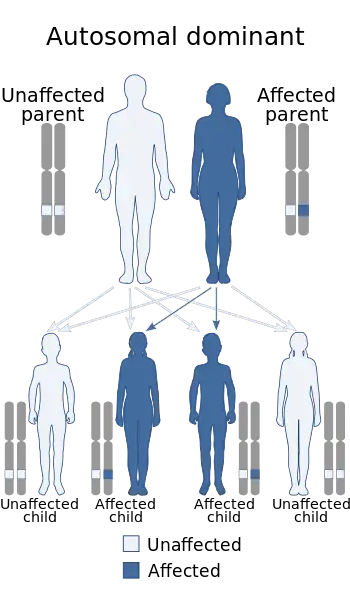

| Papillorenal syndrome has an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance | |

Papillorenal syndrome is an autosomal dominant[2] genetic disorder marked by underdevelopment (hypoplasia) of the kidney and colobomas of the optic nerve.[3]

Signs and symptoms

Ocular

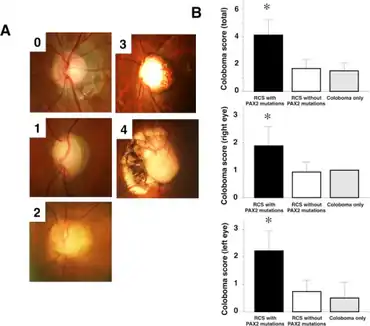

Ocular disc dysplasia is the most notable ocular defect of the disease. An abnormal development in the optic stalk causes optic disc dysplasia, which is caused by a mutation in the Pax2 gene.[4] The nerve head typically resembles the morning glory disc anomaly, but has also been described as a coloboma.[4] A coloboma is the failure to close the choroid fissure, which is the opening from the ventral side of the retina in the optic stalk.[5] Despite the similarities with coloboma and morning glory anomaly, significant differences exist such that optic disc dysplasia cannot be classified as either one entity.[6] Optic disc dysplasia is noted by an ill-defined inferior excavation, convoluted origin of the superior retinal vessels, excessive number of vessels, infrapapillary pigmentary disturbance, and slight band of retinal elevation adjacent to the disk.[6] Some patients have normal or near normal vision, but others have visual impairment associated with the disease, though it is not certain if this is due only to the dysplastic optic nerves, or a possible contribution from macular and retinal malformations.[4] The retinal vessels are abnormal or absent, in some cases having small vessels exiting the periphery of the disc. There is a great deal of clinical variability.[4]

Kidney

The most common malformation in patients with the syndrome is kidney hypodysplasia, which are small and underdeveloped kidneys, often leading to end-stage renal disease (ESRD).[7] Estimates show approximately 10% of children with hypoplastic kidneys are linked to the disease.[8] Many different histological abnormalities have been noted, including:

- decrease in nephron number associated with hypertrophy

- focal segmental glomerulosclerosis

- interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy

- multicystic dysplastic kidney[7]

Up to one-third of diagnosed patients develop end stage kidney disease, which may lead to complete kidney failure.[7]

Causes

Pax2 mutations

The majority of mutations occur in exons 2,3 and 4, which encode the paired domain and frame shift mutations that lead to a null allele.[9] The missense mutations appear to disrupt hydrogen bonds, leading to decreased transactivation of Pax2, but do not seem to effect nuclear localization, steady state mRNA levels, or the ability of Pax2 to bind to its DNA consensus sequence.[10] Mutations related to the disease have also been noted in exons 7,8, and 9, with milder phenotypes than the other mutations.[7]

Recent studies

Pax2 is expressed in the kidney, midbrain, hindbrain, cells in the spinal column, developing ear and developing eye. Homozygous negative Pax2 mutation is lethal, but heterozygote mutants showed many symptoms of papillorenal syndrome, including optic nerve dysplasia with abnormal vessels emerging from the periphery of the optic cup and small dysplasic kidneys. It is shown that Pax2 is under upstream control of Shh in both mice and zebrafish, which is expressed in the precordal plate.[7]

Other genes

Approximately half of patients with papillorenal syndrome do not have defects in the Pax2. This suggests that other genes play a role in the development of the syndrome, though few downstream effectors of Pax2 have been identified.[7]

Genetic

Papillorenal syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder that results from a mutation of one copy of the Pax2 gene, located on chromosome 10q24.3-q25.1.[2][11] The gene is important in the development of both the eye and the kidney. Autosomal dominant inheritance indicates that the gene responsible for the disorder is located on an autosome (chromosome 10 is an autosome), and only one defective copy of the gene is sufficient to cause the disorder, when inherited from a parent who has the disorder.

Diagnosis

Clinical findings in the kidney

- Hypoplastic kidneys: Characterized by hypoplasia or hyperechogenicity. This typically occurs bilaterally, but there are also exceptions in which one kidney may be notably smaller while the other kidney is normal sized.

- Hypodysplasia (RHD): Characterized histologically by reduced number of nephrons, smaller kidney size, or disorganized tissue.

- Multicystic Dysplastic Kidney: Characterized histologically, displaying cysts or dysplasia. Shows disorganization of kidneys, and occurs in about 10% of patients with papillorenal syndrome.

- Oligomeganephronia: Fewer than normal glomeruli, with a notable size increase.

- Chronic kidney disease and end-stage kidney disease (ESKD)

- Vesicoureteral reflux[12]

Clinical findings in the eye

Dysplasia of the optic nerve (most common)

The severity varies, but the most severe form results in an enlarged disc where vessels exit from the periphery instead of the center. Redundant fibroglial tissue also is seen in severe cases. Milder forms of dysplasia exhibit missing portions of the optic disc located in the optic nerve pit. The least severe form of papillorenal disease shown in the eye is the exiting of blood vessels from the periphery that do not disturb the shape of the eye. Other eye malformations include scleral staphyloma, which is the bulging of the eye wall. There can also be retinal thinning and myopia. Additionally, there can be an optic nerve cyst, which is dilation of the optic nerve posterior to the globe; which most likely results from incomplete regression of the primordial optic stalk and the filling of this area with fluid. Retinal coloboma is also common, which is characterized by the absence of retinal tissue in the nasal ventral portion of the retina. However, this is an extremely rare finding.[12]

Molecular genetic testing

Sequence analysis shows that Pax2 is the only known gene associated with the disease. Mutations in Pax2 have been identified in half of renal coloboma syndrome victims.[12]

Treatment

- Management of the disease should be focused on preventing end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) and/or vision loss. The treatment of hypertension may also preserve renal function. Renal replacement therapy is recommended, and vision experts may provide assistance to adapt to continued vision loss.[12]

- Kidney transplant is also an option.[4] Treatment plans seem to be limited, as there is a large focus on the prevention of papillorenal syndrome and its implications. People with congenital optic nerve abnormalities should seek ophthalmologists regularly and use protective lenses. If abnormalities are present, a follow up with a nephrologist should be achieved to monitor renal function and blood pressure. Since the disease is believed to be caused by Pax2 mutations and is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner, family members may be at risk and relatives should be tested for possible features. About half of those diagnosed with the disease have an affected parent, so genetic counseling is recommended.

- Prenatal testing is another possibility for prevention or awareness, and this can be done through molecular genetic testing or ultrasounds at later stages of pregnancy. Additionally, preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) should be considered for families where papillorenal syndrome is known to be an issue.[12]

References

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 120330

- 1 2 Ford, B.; Rupps, R.; Lirenman, D.; Van Allen, M. I.; Farquharson, D.; Lyons, C.; Friedman, J. M. (Mar 2001). "Renal-coloboma syndrome: Prenatal detection and clinical spectrum in a large family". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 99 (2): 137–141. doi:10.1002/1096-8628(2000)9999:999<00::AID-AJMG1143>3.0.CO;2-F. PMID 11241473.

- ↑ Parsa, C. F.; Silva, E. D.; Sundin, O. H.; Goldberg, M. F.; De Jong, M. R.; Sunness, J. S.; Zeimer, R.; Hunter, D. G. (2001). "Redefining papillorenal syndrome: An underdiagnosed cause of ocular and renal morbidity". Ophthalmology. 108 (4): 738–749. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00661-8. PMID 11297491.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Papillorenal Syndrome | Hereditary Ocular Diseases". disorders.eyes.arizona.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-06-10. Retrieved 2022-04-25.

- ↑ Boffa LC, Vidali G, Allfrey VG (March 1976). "Changes in nuclear non-histone protein composition during normal differentiation and carcinogenesis of intestinal epithelial cells". Exp. Cell Res. 98 (2): 396–410. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(76)90449-3. PMID 1253852.

- 1 2 "Atlas of Ophthalmology". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2022-04-25.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Schimmenti, L. A.; Eccles, M. R.; Pagon, R. A.; Bird, T. D.; Dolan, C. R.; Stephens, K.; Adam, M. P. (1993). "Renal Coloboma Syndrome". PMID 20301624.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Renal coloboma syndrome: MedlinePlus Genetics". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 2022-04-19. Retrieved 2022-04-25.

- ↑ "Biology Department". 2016-04-10. Archived from the original on 2022-06-10. Retrieved 2022-04-25.

- ↑ Alur RP, Vijayasarathy C, Brown JD, et al. (March 2010). "Papillorenal syndrome-causing missense mutations in PAX2/Pax2 result in hypomorphic alleles in mouse and human". PLOS Genet. 6 (3): e1000870. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000870. PMC 2832668. PMID 20221250.

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 167409

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bower MA, Schimmenti LA, Eccles MR (2007). PAX2-Related Disorder. GeneReviews [Internet]. University of Washington, Seattle. PMID 20301624. Archived from the original on 2022-01-20. Retrieved 2022-04-25.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

- GeneReview/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on Renal Coloboma Syndrome Archived 2022-01-20 at the Wayback Machine

- Papillorenal syndrome at NIH's Office of Rare Diseases

- NCBI Genetic Testing Registry Archived 2022-06-10 at the Wayback Machine