Ohtahara syndrome

| Ohtahara syndrome[1] | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Early infantile epileptic encephalopathy with burst-suppression | |

Ohtahara syndrome (OS), also known as early infantile epileptic encephalopathy (EIEE)[2] is a progressive epileptic encephalopathy. The syndrome is outwardly characterized by tonic spasms and partial seizures within the first few months of life,[3] and receives its more elaborate name from the pattern of burst activity on an electroencephalogram (EEG). It is an extremely debilitating progressive neurological disorder, involving intractable seizures and severe intellectual disabilities. No single cause has been identified, although in many cases structural brain damage is present.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Ohtahara syndrome is rare and the earliest-appearing age-related epileptic encephalopathy, with seizure onset occurring within the first three months of life, and often in the first ten days.[5] Many, but not all, cases of OS evolve into other seizure disorders, namely West syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome.[4]

The primary outward manifestation of OS is seizures, usually presenting as tonic seizures (a generalized seizure involving a sudden stiffening of the limbs).[6] Other seizure types that may occur include partial seizures, clusters of infantile spasms, and, rarely, myoclonic seizures. In addition to seizures, children with OS exhibit profound mental and physical disabilities.

Clinically, OS is characterized by a "burst suppression" pattern on an EEG. This pattern involves high voltage spike wave discharge followed by little brain wave activity.[4]

It is named for the Japanese neurologist Shunsuke Ohtahara (1930–2013), who identified it in 1976.

Both female and male infants born with OS may experience symptoms while asleep or awake. Many children die from OS within their first 2 years of life, while those who survive maintain physical and cognitive disabilities such as excessive fatigue, difficulty feeding, chest infections and slow developmental progress.[2][7] Although birth history and head size of infants is typically normal, microcephaly may occur.[3] Certain genetic variants manifest with additional signs such as dyskinetic movements and an atypical Rett-syndrome appearance.[8]

- Tonic seizures and spasms

- Muscle stiffness

- Dilated pupils

- Diplegia

- Hemiplegia

- Tetraplegia

- Ataxia

- Dystonia

Causes

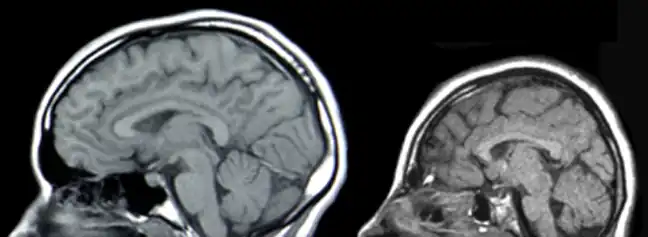

No single cause of OS has been identified. In most cases, there is severe atrophy of both hemispheres of the brain. Cerebral malformations such as hemimegalencephaly, porencephaly, Aicardi syndrome, olivary-dentate dysplasia, agenesis of mamillary bodies, linear sebaceous nevus syndrome, cerebral dysgenesis, and focal cortical dysplasia have been noted as suspect causes.[9]

Although it was initially published that no genetic connection had been established,[10] several genes have since become associated with Ohtahara syndrome. It can be associated with mutations in ARX,[11][12] CDKL5,[13] SLC25A22,[14] STXBP1,[15] SPTAN1,[16] KCNQ2,[17] ARHGEF9,[18] PCDH19,[19] PNKP,[20] SCN2A,[21] PLCB1,[22] SCN8A,[23] ST3GAL3,[2] TBC1D24,[2] BRAT1 [2] and likely others.

Less often, the root of the disorder is an underlying metabolic syndrome, though mitochondrial disorders, non-ketotic hyperglycinemia, and enzyme deficiency remain elusive as causes. Their mechanisms are not entirely known.[3]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based on the clinical presentation and on typical electroencephalographic patterns based on time of onset.[24][2] Typically, onset of seizures and spasms have been indicative of OS diagnosis, while MRI and Abormal EEG "burst suppression" pattern can confirm. Genetic testing with chromosomal microarray analysis followed by an epilepsy gene panel or whole exome sequencing may be considered after MRI imaging has been exhausted.[25][26]

Differential diagnoses between other epileptic encephalopathies such as West syndrome or Lennox-Gastaut syndrome are distinguished by myoclonic seizures and differences in spike-and-wave patterns on EEG.[27]

Treatment

Treatment outlook is poor. Anticonvulsant drugs and glucocorticoid steroids may be used to try to control the seizures, but their effectiveness is limited. Most therapies are related to symptoms and day-to-day living.[4] For cases related to focal brain lesions, epilepsy surgery or functional hemispherectomy may be considered.[7][3][28] Risk factors include infection, blood loss, loss of vision, speech, memory, or movement.

Therapy for those with OS are based on severity of seizure activity and are supportive in nature. This may include treatment for abnormal muscle tone, stomach or lung problems.[7] A ketogenic diet may be suggested for reduction of symptoms.[2] Should the child survive past the age of three, vagus nerve stimulation could be considered.[2] No recent findings allude to preventive methods for pregnant mothers.

Prognosis

Prognosis is poor for infants with OS, and can be characterized by management of seizures, effects of secondary symptoms and shortened life span (up to 3 years of age). Survivors have severe psychomotor impairments and are dependent on their caretaker for support. Family members of infants with OS may consult with a palliative care team as symptoms may worsen or develop. Death is often due to strain from seizure activity, pneumonia or other complications from motor disabilities.[8]

Prospects of recovering from OS after hemispherectomy surgery has been shown to be favorable, with patients experiencing "catch up" in development.[29]

Epidemiology

Incidence has been estimated at 1/100 000 births in Japan and 1/50,000 births in the U.K.[30] Approximately 100 cases total have been reported but this may be an underestimate. since OS neonates with early death may escape clinico-EEG diagnosis.[9] Male cases slightly predominate those of females.

Current research

Currently, only one clinical trial has been performed to examine the efficacy of high-definition (HD) transcranial direct-current stimulation (HD-tDCS) in reducing epileptiform activity.[31]

Society and culture

Ivan Cameron, son of David Cameron, former leader of the British Conservative Party and Prime Minister of the UK, was born with the condition and cerebral palsy. He died aged six on 25 February 2009, while his father was still opposition leader.[32]

Dr William H. Thomas, a United States doctor, has two daughters with this condition. He spoke about them during a PBS interview.[33]

References

- ↑ Berg AT, Berkovic SF, Brodie MJ, et al. (April 2010). "Revised terminology and concepts for organization of seizures and epilepsies: report of the ILAE Commission on Classification and Terminology, 2005-2009". Epilepsia. 51 (4): 676–85. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02522.x. PMID 20196795.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Ohtahara Syndrome". Epilepsy Foundation. Retrieved 2019-12-13.

- 1 2 3 4 "OHTAHARA SYNDROME". www.epilepsydiagnosis.org. Archived from the original on 2019-12-13. Retrieved 2019-12-13.

- 1 2 3 4 National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (5 December 2008). "NINDS Ohtahara Syndrome Information Page". Archived from the original on 28 February 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-10.

- ↑ Ohtahara S, Ishida T, Oka E, et al. (1976). "[On the specific age dependent epileptic syndrome: the early-infantile epileptic encephalopathy with suppression-burst]". No to Hattatsu (in 日本語). 8: 270–9.

- ↑ Holmes, Gregory L. (January 2004). "Tonic". Epilepsy.com/Professionals. Archived from the original on 2013-03-16. Retrieved 2007-11-26.

- 1 2 3 "Ohtahara Syndrome Information Page | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke". www.ninds.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2022-01-20. Retrieved 2019-12-13.

- 1 2 RESERVED, INSERM US14-- ALL RIGHTS. "Orphanet: Early infantile epileptic encephalopathy Ohtahara syndrome". www.orpha.net. Archived from the original on 2017-11-16. Retrieved 2019-12-13.

- 1 2 "Ohtahara Syndrome". Epilepsy Foundation. Archived from the original on 2019-06-16. Retrieved 2019-12-13.

- ↑ Nabbout, Rima (July 2004). "Early infantile epileptic encephalopathy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-30. Retrieved 2021-11-21.

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 308350

- ↑ Kato M, Saitoh S, Kamei A, et al. (August 2007). "A Longer Polyalanine Expansion Mutation in the ARX Gene Causes Early Infantile Epileptic Encephalopathy with Suppression-Burst Pattern (Ohtahara Syndrome)". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81 (2): 361–6. doi:10.1086/518903. PMC 1950814. PMID 17668384.

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 300203

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 609302

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 602926

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 182810

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 602235

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 300429

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 300460

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 605610

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 182390

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 607120

- ↑ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 600702

- ↑ Beal C, Cherian K, Moshe SL, et al. (2012). "Early-Onset Epileptic Encephalopathies: Ohtahara Syndrome and Early Myoclonic Encephalopathy". Pediatric Neurology. 47 (5): 317–23. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2012.06.002. PMID 23044011. Archived from the original on 2022-01-20. Retrieved 2021-11-21.

- ↑ "Early Infantile Epileptic Encephalopathy". Centogene. 2017-07-20. Archived from the original on 2019-11-06. Retrieved 2019-12-13.

- ↑ "CentoPortal ®". www.centoportal.com. Archived from the original on 2022-01-20. Retrieved 2019-12-13.

- ↑ RESERVED, INSERM US14-- ALL RIGHTS. "Orphanet: Early infantile epileptic encephalopathy". www.orpha.net. Archived from the original on 2019-12-05. Retrieved 2019-12-13.

- ↑ "Aaron's Ohtahara Foundation". sites.google.com. Archived from the original on 2022-01-20. Retrieved 2019-12-13.

- ↑ Malik, Saleem I.; Galliani, Carlos A.; Hernandez, Angel W.; Donahue, David J. (December 2013). "Epilepsy surgery for early infantile epileptic encephalopathy (ohtahara syndrome)". Journal of Child Neurology. 28 (12): 1607–1617. doi:10.1177/0883073812464395. ISSN 1708-8283. PMID 23143728. S2CID 21646215.

- ↑ "Maternal mortality ratio in selected countries, 2015". 2016-10-24. doi:10.1787/eco_surveys-idn-2016-graph65-en.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Examining the Efficacy of tDCS in the Attenuation of Epileptic Paroxysmal Discharges and Clinical Seizures - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov". clinicaltrials.gov. 7 November 2016. Archived from the original on 2022-01-20. Retrieved 2019-12-13.

- ↑ "Cameron's 'beautiful boy' dies". BBC News Online. 25 February 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-02-26. Retrieved 2009-03-10.

- ↑ "Nursing Home Alternative". PBS. 2002-02-27. Archived from the original on 2017-04-04. Retrieved 2021-11-21.

External links

| Classification |

|---|