Mowat–Wilson syndrome

| Mowat–Wilson syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Hirschsprung disease-intellectual disability syndrome | |

| |

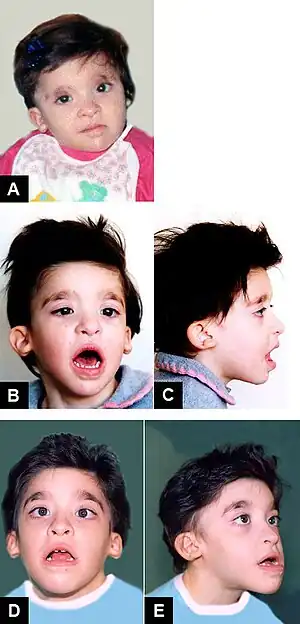

| Mowat–Wilson syndrome, clinical features of Patient 2 at age: (A) 1 year and 6 months; (B–C) 3 years and 5 months; (D–E) 8 years and 1 month. | |

| Differential diagnosis | Smith Lemli Opitz syndrome, Angelman syndrome, Goldberg Shprintzen megacolon syndrome |

| Treatment | Supportive care |

Mowat–Wilson syndrome is a rare genetic disorder that was clinically delineated by David R. Mowat and Meredith J. Wilson in 1998.[1][2]

Signs and symptoms

This autosomal dominant disorder is characterized by a number of health defects including Hirschsprung disease, intellectual disability, epilepsy,[3] delayed growth and motor development, congenital heart disease, genitourinary anomalies and absence of the corpus callosum. However, Hirschsprung's disease is not present in all infants with Mowat–Wilson syndrome and therefore it is not a required diagnostic criterion.[4] Distinctive physical features include microcephaly, narrow chin, cupped ears with uplifted lobes with central depression, deep and widely set eyes, open mouth, wide nasal bridge and a shortened philtrum.

People with this condition have severe intellectual disability in almost all cases, however, a small minority have moderate intellectual disability. Speech is typically limited or absent. Many of those with Mowat–Wilson syndrome also have a distinctive open mouthed, smiling expression and friendly personalities.[5]

Causes

The disorder is expressed in an autosomal dominant fashion and may result from a de novo loss of function mutation or total deletion of the ZEB2 gene located on chromosome 2q22.[6]

Diagnosis

Mowat–Wilson syndrome (MWS) can be diagnosed clinically on the basis of moderate to severe intellectual disability in the presence of characteristic facial features (widely spaced eyes, broad eyebrows with a medial flare, low-hanging columella, prominent or pointed chin, open-mouth expression, and uplifted earlobes with a central depression — coined as orecchiette ears given their resemblance to the pasta). Other clinical features can include congenital heart defects, Hirschsprung disease or chronic constipation, genitourinary anomalies (particularly hypospadias in males), and hypogenesis or agenesis of the corpus callosum. Speech is typically limited to a few words or is absent, with relative preservation of receptive language skills. Growth restriction with microcephaly and seizure disorder are also common. Most affected people have a happy demeanor and a wide-based gait that can sometimes be confused with Angelman syndrome. The diagnosis of MWS confirmed by demonstrating a pathogenic variant (mutation) in the ZEB2 gene by molecular genetic testing.[7]

Treatment

To date, there is no cure for MWS. Affected individuals should see a pediatrician or adult physician at least annually to monitor growth, development, seizures and general health and well-being. Developmental potential is maximized through the use of physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech pathology. Medical subspecialist care may be required if other organs are involved (e.g., a cardiologist and/or cardiac surgeon for congenital heart disease, gastroenterologist and or surgeon for Hirschsprung's disease or constipation.[7]

Prognosis

There is no cure for this syndrome. Treatment is supportive and symptomatic. All children with Mowat–Wilson syndrome required early intervention with speech therapy, occupational therapy and physical therapy.[4]

References

- ↑ Mowat, DR; Croaker, GD; Cass, DT; Kerr, BA; Chaitow, J; Adès, LC; Chia, NL; Wilson, MJ (1998). "Hirschsprung disease, microcephaly, mental retardation, and characteristic facial features: Delineation of a new syndrome and identification of a locus at chromosome 2q22-q23". Journal of Medical Genetics. 35 (8): 617–23. doi:10.1136/jmg.35.8.617. PMC 1051383. PMID 9719364.

- ↑ "Medical Advisory Board". Mowat–Wilson Syndrome Foundation. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ↑ Cordelli, DM; Garavelli, L; Savasta, S; Guerra, A; Pellicciari, A; Giordano, L; Bonetti, S; Cecconi, I; et al. (2013). "Epilepsy in Mowat–Wilson syndrome: Delineation of the electroclinical phenotype". American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 161A (2): 273–84. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.35717. PMID 23322667. S2CID 24934018.

- 1 2 Todo A, Harrington JW. New-onset seizures in infant with square facies, hypospadias, and Hirschsprung disease Archived 2020-05-04 at the Wayback Machine. Consultant for Pediatricians. 2010;9:103-107.

- ↑ "Mowat-Wilson syndrome: MedlinePlus Genetics". Archived from the original on 2022-05-15. Retrieved 2022-06-10.

- ↑ "ZEB2 - zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 2". HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee. 29 August 2019. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- 1 2 Adam, Margaret P; Conta, Jessie; Bean, Lora JH (1993). "Mowat-Wilson Syndrome". GeneReviews. National Library of Medicine. PMID 20301585. Archived from the original on 2022-06-17. Retrieved 2022-06-10.

Further reading

- Cerruti Mainardi, P; Pastore, G; Zweier, C; Rauch, A (2004). "Mowat–Wilson syndrome and mutation in the zinc finger homeo box 1B gene: A well defined clinical entity". Journal of Medical Genetics. 41 (2): e16. doi:10.1136/jmg.2003.009548. PMC 1735678. PMID 14757866.

- Mowat, DR; Wilson, MJ; Goossens, M (2003). "Mowat–Wilson syndrome". Journal of Medical Genetics. 40 (5): 305–10. doi:10.1136/jmg.40.5.305. PMC 1735450. PMID 12746390.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|

- GeneReview of Mowat–Wilson syndrome Archived 2010-06-02 at the Wayback Machine